Strategic Approaches to Reduce Endotoxin Contamination in Recombinant Proteins: From Prevention to Removal

This comprehensive article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with advanced strategies for controlling endotoxin contamination throughout recombinant protein production.

Strategic Approaches to Reduce Endotoxin Contamination in Recombinant Proteins: From Prevention to Removal

Abstract

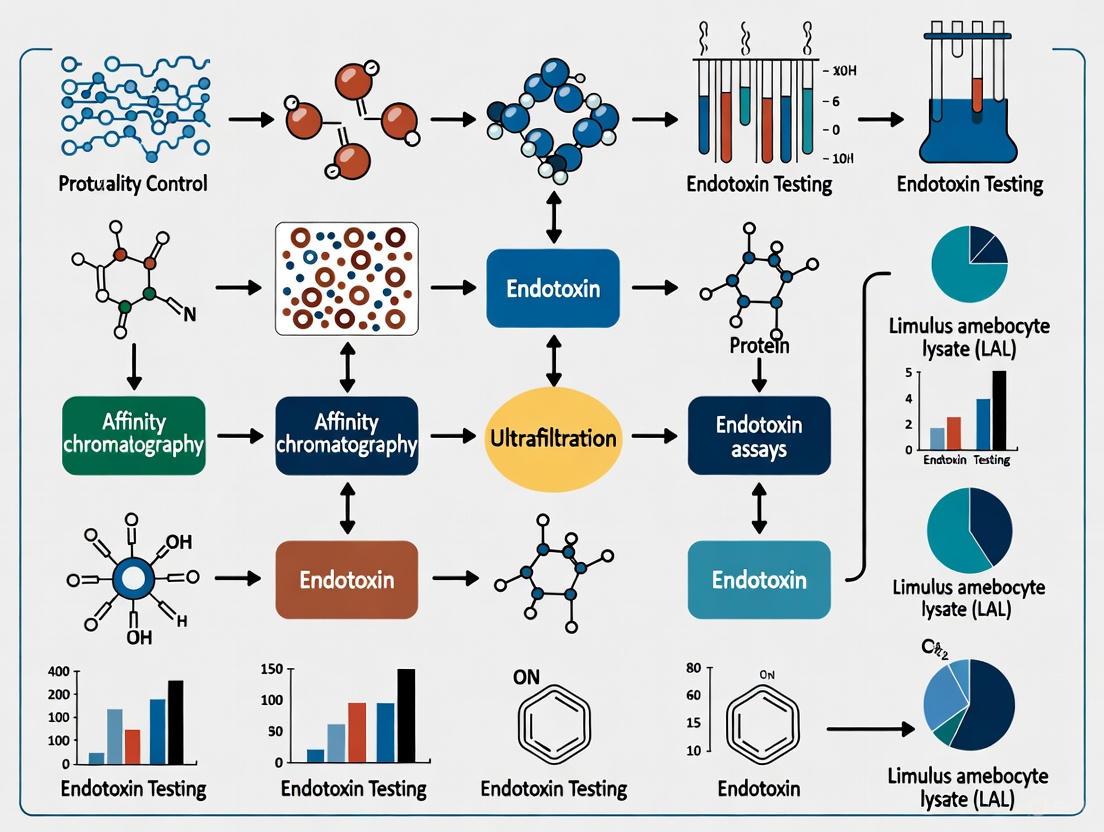

This comprehensive article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with advanced strategies for controlling endotoxin contamination throughout recombinant protein production. Covering foundational principles to cutting-edge methodologies, we explore preventive controls, comparative analysis of removal techniques including ultrafiltration, chromatography, and novel affinity methods, troubleshooting for common challenges like Low Endotoxin Recovery (LER), and validation frameworks for compliance with global regulatory standards. The content synthesizes current industry practices with emerging research to deliver a actionable guide for ensuring product safety and efficacy in biomedical applications.

Understanding Endotoxin Contamination: Risks, Sources, and Regulatory Foundations

What Are Endotoxins? Defining LPS Structure and Pyrogenic Effects

What are endotoxins and why are they a problem in research?

Endotoxins, more commonly known scientifically as Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), are complex molecules found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella [1] [2]. They are collectively termed "endotoxins" because they are toxins released when the bacterial cell disintegrates, as opposed to "exotoxins" which are secreted by live bacteria [3] [4].

For researchers, especially those working with recombinant proteins and cell cultures, endotoxin contamination represents a significant problem. Even minute amounts of endotoxin can have substantial impacts on experimental outcomes and product safety [4] [5].

- Immune System Activation: LPS is a potent activator of the mammalian immune system. It binds to the CD14/TLR4/MD2 receptor complex on immune cells like monocytes and macrophages, triggering a robust pro-inflammatory response [1] [4]. This can lead to the secretion of cytokines, fever, and in severe cases, septic shock [1] [2].

- Experimental Artifacts: In cell-based assays, endotoxin contamination can cause unintended immune activation, distorting research results and leading to false conclusions [5]. For example, in studies involving microglia or other immune cells, endotoxin-contaminated tau protein can provoke an inflammatory response that is misinterpreted as a disease-specific effect [6].

- Regulatory and Safety Concerns: For biological pharmaceuticals and therapeutics intended for parenteral (injected) use, strict limits on endotoxin levels are enforced. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) sets a limit of 5 Endotoxin Units (EU) per kg of body weight for products administered intravenously over an hour [4] [7]. Contamination can lead to adverse patient reactions, including fever and shock, and result in product recalls [3].

What is the structure of LPS?

The potent biological effects of endotoxins are directly linked to their unique molecular architecture. LPS are large, amphipathic molecules, meaning they have both hydrophilic (water-attracting) and hydrophobic (water-repelling) regions [1]. Their structure can be divided into three distinct domains, each with a specific function.

Domains of LPS Structure

| Domain | Chemical Composition | Function and Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid A [1] [2] | A phosphorylated glucosamine disaccharide decorated with multiple fatty acid chains (e.g., often hexa-acylated in E. coli) [2]. | - Hydrophobic anchor that embeds LPS in the bacterial outer membrane [1].- The endotoxic center responsible for most of the biological toxicity; a potent pyrogen [1] [2]. |

| Core Oligosaccharide [1] [2] | An inner and outer core containing sugars like heptose and 3-Deoxy-D-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid (KDO) [1]. | - Connects Lipid A to the O-antigen [1].- Contributes to membrane stability [2].- Less variable than the O-antigen [1]. |

| O-Antigen (O Polysaccharide) [1] [2] | A repeating, variable chain of oligosaccharides (2-8 sugars per unit) projecting out from the core [2]. | - The most variable part of LPS, determining serological specificity (e.g., over 160 variants in E. coli) [1] [2].- Helps bacteria evade host immune defenses [2]. |

The following diagram illustrates the spatial relationship of these three domains within the bacterial outer membrane.

Some bacteria, such as Neisseria and Haemophilus, produce a form of LPS that lacks the long O-antigen chain. This is known as Lipooligosaccharide (LOS) and is often associated with increased virulence and ability to mimic host molecules [1].

How do I detect and measure endotoxin contamination?

Detecting and quantifying endotoxin levels is a critical quality control step. The following table compares the primary methods available.

Endotoxin Detection Methods

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity & Key Features | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) [3] [7] | Lysate from horseshoe crab blood cells clots or changes in the presence of endotoxin. | - Gel-clot: Qualitative (clot/not); sensitivity ~0.03 EU/mL [4].- Turbidimetric: Measures turbidity change; quantitative [4].- Chromogenic: Measures color change from substrate hydrolysis; quantitative [4]. | USP standard for pharmaceutical and device testing [7]. |

| Recombinant Assays [7] | Uses recombinant enzymes instead of natural crab lysate to detect endotoxin. | - Avoids use of animal-derived components.- May have longer incubation times or reduced dynamic range. | Considered an alternative method; may require additional validation [7]. |

| Fluorescent LAL Assays (e.g., Qubit) [7] | A subset of LAL assays that uses fluorescence for detection. | - High sensitivity (0.01 - 10.0 EU/mL).- Easy-to-use workflow with automated calculation on compatible fluorometers. | Can be validated to comply with Pharmacopeia standards [7]. |

| Rabbit Pyrogen Test [3] [4] | Measures fever response in rabbits after injection of a test sample. | - In vivo test.- Less sensitive than LAL tests.- Requires more time, expense, and specialized training. | Official method in pharmacopeias, but largely supplanted by in vitro LAL tests [3]. |

For any LAL-based method, it is crucial to perform a validation to check for assay interference. This involves a "spike recovery" test, where a known amount of endotoxin is added to the sample. The recovery of this spike should be between 50-200% (with many labs aiming for 75-150%) to ensure the sample matrix itself is not inhibiting or enhancing the assay reaction [7] [8].

What methods can remove endotoxins from protein samples?

Removing bound endotoxin from recombinant proteins, especially those expressed in E. coli, is a common challenge. Endotoxin-protein interactions are often hydrophobic and ionic, making them difficult to disrupt without affecting the protein of interest [4]. The table below summarizes common removal techniques.

Endotoxin Removal Methods

| Method | Mechanism of Action | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|

| Triton X-114 Phase Separation [6] [4] | Exploits the amphiphilic nature of LPS. Upon heating, the detergent solution separates into detergent-rich (containing LPS) and aqueous phases (containing protein). | Proteins stable in non-ionic detergents; a key step in protocols for sensitive cell culture work [6]. |

| Ion-Exchange Chromatography [4] | Separates based on charge. The negative charge of the LPS core polysaccharide can be exploited to bind it to a resin while the protein flows through, or vice versa. | Proteins with a charge significantly different from the negative charge of LPS. |

| Affinity Adsorbents [4] | Uses resins with immobilized molecules (e.g., polymyxin B) that have a high binding affinity for the Lipid A portion of LPS. | A highly specific method for polishing steps to remove trace endotoxin. |

| Gel Filtration Chromatography [4] | Separates molecules based on size. If the protein and LPS aggregates are of sufficiently different sizes, they can be separated. | Proteins with a molecular weight significantly different from LPS aggregates. |

Detailed Protocol: Triton X-114 Phase Separation

This protocol is highly effective for removing bound endotoxin from recombinant proteins, as demonstrated for tau protein used in microglial cell culture [6].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Treat with Triton X-114: In a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube, add 25% Triton X-114 stock solution to your protein sample to achieve a final concentration of 2% detergent. It is recommended to use a protein concentration greater than 0.2 mg/mL to minimize losses [6].

- Incubate Cold: Incubate the mixture at 4°C for one hour with constant rotation. This allows the detergent to interact with the endotoxin [6].

- Induce Phase Separation: Transfer the tube to a 37°C water bath for 10 minutes. The solution will become turbid as it separates into two phases [6].

- Centrifuge: Centrifuge the tube at 20,000 x g for 20 minutes at 37°C. This will complete the phase separation, resulting in a small, dense detergent-rich pellet (containing the endotoxin) and a top aqueous phase (containing your protein) [6].

- Collect Aqueous Phase: Carefully collect the top aqueous layer without disturbing the bottom detergent phase. If the interface is disturbed, repeat the centrifugation [6].

- Repeat Cycles: To ensure maximum endotoxin removal, repeat the treatment cycle (steps 1-5) two more times for a total of three phase separations [6].

- Remove Residual Detergent: After the third cycle, pass the collected aqueous phase through a detergent-removal spin column (following manufacturer's instructions) to eliminate any residual Triton X-114 from the final protein preparation [6].

Verification of Removal: After purification, it is essential to quantify the remaining endotoxin levels using an LAL assay [6]. Furthermore, a functional validation using a cell-based assay, such as monitoring the inflammatory response in endotoxin-sensitive cells (e.g., HEK-Blue hTLR4 reporter cells or iPSC-derived microglia), is highly recommended to confirm the biological relevance of the removal [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Endotoxin Control

| Reagent / Material | Function in Endotoxin Control |

|---|---|

| Triton X-114 [6] | A non-ionic detergent used in phase separation protocols to solubilize and separate endotoxin from proteins. |

| Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) [3] [7] | The key reagent derived from horseshoe crab blood used in the majority of in vitro endotoxin detection tests. |

| Endotoxin Standards [7] | Known concentrations of endotoxin used to calibrate LAL assays and generate standard curves for accurate quantification. |

| Detergent Removal Spin Columns [6] | Used to clean up residual detergents (like Triton X-114) from protein samples after endotoxin removal procedures. |

| Endotoxin-Free Water & Buffers [3] [5] | Critical base reagents used in all steps of protein preparation and testing to prevent the introduction of new contamination. |

| Endotoxin-Free Plastics [7] [5] | Specially manufactured labware (tubes, tips, plates) that do not leach endotoxins, which can easily adsorb to plastics. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are my mammalian cell cultures activating unexpectedly, showing high cytokine secretion? This is a classic sign of endotoxin contamination. LPS is a potent activator of immune cells like macrophages, triggering cytokine release. You should screen your culture media, supplements (e.g., FBS), and any recombinant proteins or other additives added to the culture using an LAL test [4] [5].

Q2: My recombinant protein is expressed in E. coli and is very "sticky." How can I prevent endotoxin contamination from the start? Prevention is always better than cure. Use endotoxin-free plasmids, water, and buffers from the beginning of your protein expression and purification workflow. Store purified proteins in low endotoxin affinity plastic containers and maintain strict aseptic technique to avoid bacterial growth in your stocks [5].

Q3: I've purified my protein, but the LAL test shows high endotoxin. Can I just filter it out? No. Standard sterilizing filters (0.22 µm) remove bacteria but not the much smaller endotoxin molecules. Furthermore, endotoxins often form stable aggregates or bind tightly to your protein of interest, making them impossible to remove by simple filtration. You will need to employ a dedicated removal technique like Triton X-114 phase separation or affinity chromatography [3] [4].

Q4: Is "sterile" technique enough to control for endotoxins? No. This is a critical distinction. "Sterile" means the absence of viable microorganisms. "Endotoxin-free" means the absence of the heat-stable endotoxin molecules themselves. LPS can withstand standard autoclaving and remain fully active. Therefore, a solution can be sterile but still pyrogenic (fever-causing) due to high endotoxin levels [3] [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are endotoxins, and why are they a significant concern in pharmaceutical and research applications? Endotoxins, also known as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), are toxic components found in the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria like E. coli [9]. They are a major contaminant in recombinant proteins produced using bacterial expression systems. The primary concern is their potent biological activity; even trace amounts can trigger pyrogenic (fever) responses in patients [10]. Upon entering the bloodstream, endotoxins can cause severe immune reactions, including inflammation and septic shock, a life-threatening condition characterized by persistent hypotension and organ dysfunction despite adequate fluid resuscitation [9] [11].

Q2: My recombinant protein is intended for cell culture experiments. Why is endotoxin removal critical? Endotoxin contamination in protein preparations can cause false outcomes in research by inducing unintended cellular responses [9]. For instance, in studies involving microglia or other immune cells, endotoxins can activate inflammatory pathways, leading to the secretion of cytokines and confounding the results [6]. Therefore, effective endotoxin removal is a prerequisite for obtaining reliable and biologically relevant data from cell-based assays.

Q3: What are the most effective methods for removing endotoxins from protein solutions? Several methods are available, each with different mechanisms, efficiencies, and limitations. The choice of method depends on the nature of your protein and the required purity level.

- Affinity Chromatography: This method uses ligands (e.g., polymyxin B) that specifically bind to the lipid A portion of endotoxins. It offers high efficiency and specificity, effectively removing endotoxins while preserving the target protein [9] [12].

- Ion Exchange Chromatography: This technique exploits the strong negative charge of endotoxins. Under standard conditions (pH > 2), endotoxins bind to positively charged resins, while many target proteins flow through. It provides high efficiency and is easily scalable [9].

- Phase Separation (e.g., with Triton X-114): This is a non-chromatographic method that uses a detergent. The solution is cycled between cold and warm temperatures, causing endotoxins to partition into a detergent-rich phase, which is separated from the aqueous protein-containing phase by centrifugation. It offers moderate efficiency and is a relatively simple protocol [6] [9].

- Ultrafiltration: This physical separation method uses membranes with a specific molecular weight cutoff (e.g., 100 kDa) to retain large endotoxin aggregates while allowing smaller proteins to pass. Its efficiency is moderate and can be variable [9].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Endotoxin Removal Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Efficiency | Specificity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Chromatography | Specific ligand binding (e.g., Polymyxin B) | High [9] | High [9] | High cost; may require elevated ionic strength for elution [9] |

| Ion Exchange Chromatography | Electrostatic charge interactions | High [9] | Medium [9] | Sensitive to pH and salt conditions [9] |

| Phase Separation | Temperature-driven partitioning using detergents | Moderate (45-99%) [9] | Low [9] | Potential for trace detergent residues; may require multiple cycles [6] [9] |

| Ultrafiltration | Size-based physical separation | Moderate (28.9-99.8%) [9] | Low [9] | Ineffective at removing smaller endotoxin fragments [9] |

Q4: How do I quantify endotoxin levels to validate the success of my removal process? The Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) test is the standard and FDA-accepted method for endotoxin quantification, replacing the older rabbit pyrogen test [13]. This test is available in several formats (gel clot, turbidimetric, chromogenic). Alternatively, ELISA kits are available that can detect endotoxins with high sensitivity, down to 0.5 pg/ml [14]. For biologically relevant validation, you can use cell-based assays, such as HEK-Blue hTLR4 reporter cells, which secrete an easily detectable enzyme (SEAP) upon activation by endotoxins in a dose-dependent manner [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Endotoxin Removal with Triton X-114 Phase Separation

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Inefficient Phase Separation

- Solution: Ensure precise temperature control during the protocol. The initial incubation with Triton X-114 must be at 4°C for 1 hour with rotation to form a homogenous solution. The phase separation step must then be performed at 37°C for 10 minutes in a water bath, followed by centrifugation at 37°C [6]. The solution should appear turbid after the 37°C incubation.

Cause 2: Cross-Contamination of Phases

- Solution: After centrifugation, take extreme care when collecting the top, protein-containing aqueous phase. Do not disturb the lower, detergent-rich phase where the endotoxins reside. If the interface is disturbed, repeat the centrifugation step [6].

Cause 3: Insufficient Cleaning Cycles

Problem: Low Protein Recovery After Affinity Chromatography

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Non-Specific Binding of Target Protein

- Solution: While affinity resins like Polymyxin B are designed for specificity, some proteins may still bind non-specifically. Optimize the binding buffer's pH and ionic strength to minimize unwanted interactions while maintaining endotoxin binding. Using a different removal method, such as ion exchange chromatography, might be more suitable for your specific protein [9].

Cause 2: Protein Loss During Detergent Removal

- Solution: If using a detergent-based method followed by a detergent removal column, note that protein loss is greater if the initial protein concentration is too low. It is recommended to use a protein concentration greater than 0.2 mg/mL before proceeding with detergent removal spin columns [6].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Endotoxin Removal via Triton X-114 Phase Separation

This protocol is adapted from a published method for purifying E. coli-derived tau protein and is broadly applicable to other recombinant proteins [6].

Summary: The protocol uses the non-ionic detergent Triton X-114, which forms a homogeneous solution with the protein at low temperatures but separates into detergent-rich and aqueous phases upon warming. Endotoxins, being highly hydrophobic, partition into the detergent phase, while the target protein remains in the aqueous phase.

Graphical Workflow:

Key Resources Required:

- REAGENTS: Triton X-114, 1x DPBS, Detergent removal spin columns, Endotoxin-free water [6].

- EQUIPMENT: Microcentrifuge tubes, water baths (4°C and 37°C), centrifuge, rotation mixer.

Step-by-Step Method Details [6]:

- Add Triton X-114: In a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube, add 25% Triton X-114 stock to your protein solution to achieve a final concentration of 2% Triton X-114.

- Cold Incubation: Incubate the mixture at 4°C for 1 hour with constant rotation to form a homogenous solution.

- Warm Incubation & Phase Separation: Transfer the tube to a 37°C water bath and incubate for 10 minutes. The solution will become turbid.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the tube at 20,000 x g for 20 minutes at 37°C. This will complete the phase separation, resulting in a top aqueous layer (containing your protein) and a bottom detergent layer (containing endotoxins).

- Collect Aqueous Phase: Carefully collect the top aqueous layer without disturbing the bottom detergent layer. If the layers are mixed, repeat the centrifugation.

- Repeat Process: Subject the collected aqueous phase to the same process (steps 1-5) two more times, for a total of three phase separations.

- Remove Residual Detergent: a. Prepare a detergent removal spin column by centrifuging to remove storage solution and equilibrating it with three washes of the buffer matching your protein sample. b. Apply the Triton X-114-treated protein from Step 6 to the prepared spin column and incubate at room temperature for 2 minutes. c. Centrifuge the column to collect the purified, detergent-free protein.

- Endotoxin Quantification: Measure the endotoxin level in the final protein preparation using an LAL assay or another validated method to confirm removal efficacy [6] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Endotoxin Removal and Detection

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Triton X-114 | A non-ionic detergent used in temperature-driven phase separation to partition endotoxins away from the target protein. | MP Biomedicals [6] |

| Polymyxin B Agarose Resin | An affinity chromatography matrix. The antibiotic Polymyxin B binds specifically to the lipid A domain of endotoxin, neutralizing and removing it from solution. | EndotoxinOUT Kits [12] |

| HEK-Blue hTLR4 Cells | A reporter cell line used to biologically validate endotoxin removal. These cells express the human Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) complex and secrete SEAP upon endotoxin stimulation. | InvivoGen [6] |

| Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) | The standard reagent for quantifying endotoxin levels, based on the clotting enzyme cascade from horseshoe crab blood. | FDA-approved test method [13] |

| Endotoxin ELISA Kit | An immunoassay kit for the quantitative detection of endotoxin in various samples, such as serum, plasma, and cell culture supernatants. | Various suppliers [14] |

| Detergent Removal Spin Columns | Used to remove residual detergent (like Triton X-114) from protein samples after phase separation, preparing them for cell culture or other sensitive applications. | Thermo Scientific [6] |

Endotoxin-Induced Signaling Pathway to Septic Shock

Understanding the body's extreme response to endotoxins underscores the critical importance of their removal from therapeutics. The following diagram outlines the key pathway from exposure to the critical state of septic shock.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common sources of endotoxin contamination in a laboratory setting? The most common sources of endotoxin contamination include the bacterial hosts used for recombinant protein expression (particularly E. coli), laboratory water, and raw materials like cell culture media and sera [15] [16]. Endotoxins are lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and are released in large amounts upon bacterial death and lysis [15] [9]. A single E. coli cell contains about 2 million LPS molecules, which can easily co-purify with the target protein or DNA [15] [16]. Contamination can also spread via contaminated air, human skin, and inadequately treated glassware or plasticware [16].

Q2: How sensitive are human immune cells to endotoxin contamination? Certain human immune cells are exquisitely sensitive to endotoxins. Research shows that primary human CD1c+ dendritic cells can be activated by LPS concentrations as low as 0.002–2 ng/ml, which is equivalent to the levels of endotoxin contamination sometimes found in commercially available recombinant proteins [17]. This high sensitivity is closely correlated with high CD14 expression levels on these cells. Such low-level contamination can lead to erroneous data in experiments involving sensitive cell types.

Q3: What are the regulatory endotoxin limits for injectable products? For products administered parenterally (by injection) to humans and preclinical animal models, the endotoxin limit is set at 5.0 Endotoxin Units (EU) per kilogram of body weight when administered over one hour [18] [4]. For intrathecal injections, the limit is much stricter at 0.2 EU/kg [18]. For specific materials like Water for Injection (WFI), the limit is 0.25 EU/ml [18]. In practice, the goal for research and therapy is to maintain endotoxin levels as low as possible to prevent adverse effects.

Q4: Why is standard autoclaving insufficient for endotoxin removal? Endotoxins are remarkably heat-stable, so standard autoclaving or sterilization protocols do not effectively destroy them [16]. To destroy endotoxins on glassware, dry-heat depyrogenation at high temperatures for extended periods is required, such as 180°C for 4 hours or 250°C for 30 minutes [18] [16].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Addressing Contamination

Problem: Inconsistent Cell Culture Results or Unexplained Immune Activation

Potential Cause: Endotoxin contamination in your recombinant protein preparation or cell culture reagents.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Test Your Reagents: Use a Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay to quantify endotoxin levels in your recombinant proteins, buffers, and culture media [17] [18] [16]. The LAL assay is the standard method and comes in gel-clot, turbidimetric, and chromogenic formats [18] [4].

- Check Your Water Source: Laboratory pure water is a very common source of endotoxins. Ensure your water purification system is well-maintained and that the water used for preparing buffers and media is endotoxin-free [16] [4].

- Inspect Your Plasticware and Glassware: Use only certified pyrogen-free plasticware. Be aware that endotoxins adhere strongly to glass; standard washing and autoclaving will not remove them [15] [16].

Solutions:

- For Contaminated Proteins: Purify the protein using an appropriate endotoxin removal method (see Table 2 and the protocol below).

- For Contaminated Water: Replace with certified endotoxin-free water.

- For Contaminated Glassware: Discard if possible, or decontaminate by baking at 180°C overnight [15] [16].

Problem: Low Transfection Efficiency in Sensitive Cell Lines

Potential Cause: Endotoxin contamination in plasmid DNA preparations. Endotoxins can significantly reduce transfection efficiency, especially in primary cells and sensitive cultured cell lines [15].

Diagnostic Steps: Measure the endotoxin level in your plasmid DNA preparation using an LAL assay. The table below compares endotoxin levels and resulting transfection efficiency for different plasmid purification methods [15]:

Table 1: Endotoxin Contamination and Transfection Efficiency of Various Plasmid Prep Methods

| Plasmid Preparation Method | Endotoxin (EU†/µg DNA) | Relative Transfection Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| EndoFree Plasmid Kits | < 0.04 | 154% |

| QIAGEN Plasmid Plus Kits | < 1.0 | 100% |

| QIAGEN Plasmid Kits | 9.3 | 100% |

| 2x CsCl Gradient Centrifugation | 2.6 | 99% |

| Silica Slurry | 1230 | 24% |

Solutions: Switch to an endotoxin-removing or endotoxin-free plasmid purification kit, such as those listed in the table above, which integrate a specific step to prevent LPS from binding to the purification resin [15].

Endotoxin Removal Method Comparison

Various techniques can be employed to remove endotoxins from protein samples. The choice of method depends on the properties of your target protein and the required level of purity.

Table 2: Comparison of Endotoxin Removal Methods

| Technology | Mechanism | Efficiency | Specificity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Chromatography | Ligand (e.g., polymyxin B) binds LPS with high specificity [9] [19]. | High (≥90%) [19] | High | Can be expensive; may require pH/salt optimization [9]. |

| Ion Exchange Chromatography | Endotoxins (pI~2) bind to resin under appropriate pH conditions [9]. | High | Medium | Sensitive to pH and salt conditions; may bind highly charged target proteins [9]. |

| Phase Separation (Triton X-114) | Temperature-induced separation; endotoxins partition into detergent phase [9]. | Moderate (45-99%) [9] | Low | Risk of detergent residue; may degrade sensitive proteins [9]. |

| Ultrafiltration | Physical separation based on size of endotoxin micelles (>100 kDa) [9]. | Moderate (28.9-99.8%) [9] | Low | Fails to remove smaller endotoxin forms [9]. |

| Activated Carbon Adsorption | Non-specific adsorption to large surface area [9]. | High (~93.5%) [9] | Low | Non-selective; can cause significant product loss [9]. |

Detailed Protocol: Endotoxin Removal via Triton X-114 Phase Separation

This is a referenced protocol for removing endotoxins from recombinant proteins using Triton X-114 phase separation [9].

- Addition of Triton X-114: Add Triton X-114 to the protein sample to achieve a final concentration of 1% (v/v).

- Low-Temperature Incubation (4°C): Incubate the mixture at 4°C for 30 minutes with constant stirring to ensure complete solubilization and a homogeneous solution.

- High-Temperature Phase Separation (37°C): Transfer the sample to a 37°C water bath and incubate for 10 minutes. The solution will become cloudy as it separates into two phases: a detergent-rich phase (containing the endotoxins) and an aqueous phase (containing the target protein).

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 20,000 × g for 10 minutes at 25°C to fully separate the two phases.

- Collection of Aqueous Phase: Carefully aspirate and collect the upper, clear aqueous phase, which contains your target protein. Take care to avoid the lower, viscous detergent phase.

- Repeat Phase Separation (Optional): To further reduce endotoxin levels, subject the collected aqueous phase to 1–2 additional rounds of Triton X-114 phase separation (repeat steps 1–5).

- Endotoxin Quantification: Measure the endotoxin level in the final aqueous phase using a Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay to confirm the success of the removal process.

TLR4-Mediated Endotoxin Signaling Pathway

Endotoxins like LPS trigger a potent immune response by activating the Toll-like Receptor 4 (TLR4) pathway on innate immune cells. The following diagram illustrates the key steps in this signaling cascade, which culminates in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [17] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Endotoxin Management

Table 3: Key Reagents and Kits for Endotoxin Detection and Removal

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| LAL Assay Kit | Quantifies endotoxin levels in samples via gel-clot, turbidimetric, or chromogenic methods [18] [4]. | Routine testing of purified proteins, buffers, and culture media before use in sensitive cell-based assays. |

| High-Capacity Endotoxin Removal Resin | Affinity resin (e.g., cellulose with poly(ε-lysine)) that selectively binds endotoxins for removal from protein solutions [19]. | Rapidly cleaning up contaminated antibody or protein samples with high recovery (>85%) and >90% endotoxin removal [19]. |

| Endotoxin-Free Plasmid Kits | DNA purification kits with a dedicated buffer to remove endotoxins during the protocol [15]. | Preparing transfection-grade DNA for sensitive cells like primary immune cells, where efficiency is critical. |

| Endotoxin-Free Water & Buffers | Certified, sterile fluids guaranteed to have endotoxin levels below a specified limit (e.g., <0.005 EU/mL). | Preparing all solutions for cell culture and protein work to prevent the introduction of contaminants. |

| Triton X-114 | Non-ionic detergent used for temperature-driven phase separation to remove endotoxins from proteins [9]. | A cost-effective method for bulk removal of endotoxins from recombinant proteins that are stable in the presence of detergent. |

Bacterial Endotoxin Testing (BET) is a critical safety requirement for parenteral drugs and medical devices. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) chapter <85> and the European Pharmacopoeia (EP) chapter 2.6.14 are the harmonized standards that outline the validated methods for this testing. These chapters describe the use of Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) for detecting and quantifying endotoxins. A cornerstone of these regulations is the establishment of an endotoxin tolerance limit, calculated using the K/M formula, to ensure that a product dose, when administered to a patient, will not elicit a pyrogenic response [18]. Adherence to these standards is non-negotiable for the release of products for human use, making them foundational to quality control in recombinant protein research and pharmaceutical manufacturing.

FAQ: Understanding the Standards and Calculations

Q1: What is the fundamental purpose of USP <85> and EP 2.6.14? The primary purpose of these harmonized chapters is to provide the standards and procedures for the Bacterial Endotoxins Test (BET). This test uses Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) to detect and quantify the presence of bacterial endotoxins, which are pyrogenic lipopolysaccharides from gram-negative bacteria, in pharmaceutical products, medical devices, and raw materials [18] [20]. The test ensures patient safety by preventing febrile reactions that can be caused by contaminated injectable drugs or devices.

Q2: How is the endotoxin acceptance limit for my drug product calculated? The acceptance limit is derived from the formula K/M, which sets the maximum allowable endotoxin level per unit of product [18].

- K is the threshold pyrogenic dose of endotoxin per kilogram of body weight. It is defined as:

- 5.0 EU/kg for most intravenous and intramuscular products.

- 0.2 EU/kg for intrathecal drug products, due to the heightened sensitivity of the central nervous system.

- M is the maximum human dose per kilogram of body weight that would be administered in a single one-hour period. This is the larger of either the maximum recommended human dose from the product labeling or the dose used in the rabbit pyrogen test.

The resulting limit is expressed as EU/mL for liquids or EU/mg for solids.

Q3: Can you provide an example of the K/M calculation? Yes. The FDA provides a clear example for Cyanocobalamin Injection [18]:

- Product: Cyanocobalamin Injection

- Potency: 1000 mcg/mL

- Maximum Human Dose (M): 14.3 mcg/kg (as per product labeling)

- Endotoxin Limit (K/M): = 5.0 EU/kg / 14.3 mcg/kg = 0.35 EU/mcg

- Conversion to EU/mL: Multiply by the product potency: 1000 mcg/mL × 0.35 EU/mcg = 350 EU/mL

This means each milliliter of Cyanocobalamin Injection must contain no more than 350 Endotoxin Units (EU).

Q4: Are there specific products with predefined endotoxin limits? Yes. Certain products, like waters for pharmaceutical use, have predefined limits because the administered volume can be large and variable. According to the USP [18]:

- Water for Injection, Sterile Water for Injection, and Sterile Water for Irrigation: ≤ 0.25 EU/mL

- Bacteriostatic Water for Injection and Sterile Water for Inhalation: ≤ 0.5 EU/mL

Q5: What are the four principal LAL test methods recognized by the pharmacopeias? The four basic methods approved for end-product release testing are [18] [20]:

- Gel-Clot: A qualitative or semi-quantitative method based on clot formation.

- Turbidimetric: A quantitative method that measures the increase in turbidity.

- Chromogenic: A quantitative method that uses a synthetic chromogenic substrate to produce a color change.

- Colorimetric (Lowry protein): Another quantitative color-based method.

Table 1: Comparison of Compendial Bacterial Endotoxin Test Methods

| Method | Principle | Detection | Output | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gel-Clot | Clot formation | Visual | Qualitative / Semi-quantitative | Considered the most sensitive and accurate; less susceptible to interference [20] | Time-consuming; subjective; not automated [20] |

| Turbidimetric | Turbidity development | Spectrophotometric | Quantitative | Quantitative result based on gel-clot principle [20] | Susceptible to interference from turbid or colored samples [18] |

| Chromogenic | Chromophore release | Spectrophotometric (405 nm) | Quantitative | User-friendly; can be automated [20] | Can be interfered with by colored samples or those that cause precipitation [18] [20] |

| Kinetic Assays | Turbidity or color development over time | Spectrophotometric | Quantitative | Automated; provides insights into assay performance; improved data integrity [21] | Requires specialized instrumentation and software [21] |

Troubleshooting Common Endotoxin Testing Issues

Problem 1: Invalid Assay or Inhibition/Enhancement The test sample interferes with the LAL reaction, either inhibiting it (leading to false negatives) or enhancing it (leading to false positives).

- Root Cause: Sample properties such as pH outside the range of 6.0-8.0, high viscosity, or the presence of interfering substances like chelating agents (EDTA), denaturants, strong acids/bases, or organic solvents [18] [20].

- Solution:

- Dilution: The most common approach. Dilute the sample to reduce the concentration of the interfering substance, but ensure the dilution does not exceed the Maximum Valid Dilution (MVD).

- pH Adjustment: Neutralize the sample to a pH between 6.0 and 8.0 using endotoxin-free acid, base, or buffers [20].

- Validation: The method must be validated for the specific product. This involves spiking the product with a known amount of endotoxin and demonstrating that the recovery is within 50%-200% of the known value to prove the interference has been overcome [18].

Problem 2: High Variability in Replicate Measurements The coefficient of variation (CV) between duplicate or replicate samples exceeds the acceptable limit (often 10% or 25%) [20].

- Root Cause: Inconsistent pipetting technique, improper mixing of reagents and sample, or using reagents from different manufacturers [18].

- Solution:

Problem 3: False Positive Results The test indicates the presence of endotoxin when there is none.

- Root Cause:

- Solution:

- Use Specific Reagents: Employ LAL reagents that are resistant to β-glucans, or switch to recombinant Factor C (rFC) or recombinant Cascade Reagent (rCR) methods, which are not activated by glucans [22] [23].

- Sample Treatment: For colored samples, use a method less susceptible to interference, such as the gel-clot method [20].

Experimental Protocol: Inhibitory/Enhancing Factor Testing

This protocol is essential for validating that your sample matrix does not interfere with the LAL test, as required by USP <85> and EP 2.6.14.

Objective: To demonstrate that the sample under test does not inhibit or enhance the LAL reaction, ensuring accurate endotoxin quantification.

Materials:

- Test sample (recombinant protein solution)

- LAL reagent (gel-clot, chromogenic, or turbidimetric)

- Endotoxin Standard Control (ESC)

- Endotoxin-free water (LRW)

- Depyrogenated glassware or plasticware

- Water bath or microplate reader (temperature-controlled at 37°C ± 1°C)

Procedure:

- Preparation of Spiked Sample (Test for Interference):

- Prepare a dilution of the test sample at the planned Maximum Valid Dilution (MVD).

- Create the "Spiked Product" by adding ESC to this dilution to achieve a concentration of 2λ, where λ is the sensitivity of the LAL reagent.

- Create the "Unspiked Product" by adding an equal volume of LRW to another aliquot of the diluted sample.

Preparation of Positive Controls:

- Create a "Positive Product Control (PPC)" by adding ESC to LRW to a concentration of 2λ.

- Create a "Negative Control" using LRW only.

Assay Performance:

- Test all four preparations (Spiked Product, Unspiked Product, PPC, and Negative Control) in duplicate using your chosen LAL method (e.g., kinetic chromogenic).

- Incubate at 37°C for the specified time.

Calculation and Acceptance Criteria:

- Calculate the mean measured endotoxin concentration in the Spiked Product and the PPC.

- The test is valid if: The Negative Control shows no detectable endotoxin, and the result for the PPC is within 50%-200% of the known 2λ concentration.

- The sample is non-interfering if: The measured endotoxin concentration in the Spiked Product is within 50%-200% of the measured concentration in the PPC [18]. If recovery is outside this range, the sample is interfering, and further dilution or treatment is required.

Visualizing the Endotoxin Detection Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the key enzymatic cascades involved in traditional LAL and modern recombinant testing methods.

Diagram 1: Traditional LAL Cascade with Potential for False Positives. This pathway shows how endotoxin (LPS) activates Factors C, B, and the pro-clotting enzyme, leading to clot formation. It also highlights how (1,3)-β-D-Glucan can activate Factor G, causing a false positive result [22] [23] [20].

Diagram 2: Recombinant Factor C (rFC) Pathway. This animal-free method uses a single recombinant enzyme (Factor C) that is activated specifically by endotoxin. It then cleaves a synthetic fluorogenic substrate to produce a measurable signal. This pathway is not activated by β-Glucans, eliminating a major source of false positives [24] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Endotoxin Testing and Contamination Control

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations for Recombinant Protein Research |

|---|---|---|

| LAL Reagents | Aqueous extract from horseshoe crab blood cells used to detect endotoxin. | Available in gel-clot, chromogenic, and turbidimetric formats. Choose based on required sensitivity and equipment [22] [20]. |

| Recombinant Reagents (rFC/rCR) | Animal-free reagents produced via recombinant DNA technology. | rFC is a single protein, while rCR mimics the natural LAL cascade. Both eliminate false positives from β-glucans and support sustainability [24] [23]. |

| Endotoxin Standards | Known concentrations of endotoxin used to create standard curves and validate tests. | Critical for determining assay sensitivity (λ) and performing spike-and-recovery studies for validation [18]. |

| Endotoxin-Free Water | Water with non-detectable levels of endotoxin, used for reconstituting reagents, dilutions, and controls. | Essential for preventing background contamination that can compromise results. Typically < 0.005 EU/mL [25]. |

| Depyrogenation Tools | Processes to destroy endotoxins on equipment. | Dry Heat: The standard method for glassware (e.g., 250°C for 45 minutes) [26]. Washing: For heat-sensitive materials, use endotoxin-free detergents followed by thorough rinsing with endotoxin-free water [26]. |

| Certified Plasticware | Tubes, pipette tips, and plates tested and certified to be low in endotoxins. | Prevents the introduction of endotoxins from lab consumables. Look for certification levels such as < 0.1 EU/mL [25]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is endotoxin contamination a critical concern in my recombinant protein research? Endotoxins, or lipopolysaccharides (LPS), are potent immune stimulants found in the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria like E. coli, a common host for recombinant protein production. Even trace amounts can have profound effects:

- Extreme Sensitivity: Some primary human immune cells, like CD1c+ dendritic cells, can be activated by concentrations as low as 0.002–2 ng/ml of LPS, a range equivalent to the residual contamination found in some commercial protein preparations [17].

- Diverse Experimental Artifacts: In vitro, endotoxins can distort cell membranes, induce cytokine production (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, TNFα), alter gene expression, and cause cell death. These effects can completely obscure the true biological activity of your recombinant protein [17] [27].

- Pyrogenic Response: In vivo, endotoxins are pyrogenic and can cause fever, respiratory distress, and potentially fatal septic shock [27].

Q2: My protein is >95% pure by SDS-PAGE. Could it still have problematic endotoxin levels? Yes, absolutely. Standard purity analyses like SDS-PAGE cannot detect endotoxin contamination. A protein can be highly pure regarding other proteins but still carry significant amounts of LPS. Endotoxin is a chemical contaminant, not a proteinaceous one, and must be specifically tested for using methods like the LAL assay [17] [27].

Q3: What is the acceptable limit for endotoxin in my research samples? Acceptable limits depend on the application, particularly the sensitivity of your experimental system. For sensitive cell-based assays, especially those involving primary immune cells, you should aim for the lowest levels possible. The following table summarizes the minimal concentrations shown to activate sensitive cells, which can serve as a benchmark [17]:

| Cell Type | Minimum Activating LPS Concentration | Key Cytokines Produced |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human CD1c+ Dendritic Cells | 0.002 ng/ml | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, TNFα |

| Primary Human Monocytes | 0.02 ng/ml | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, TNFα |

| THP-1 Monocytic Cell Line | 0.2 ng/ml | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, TNFα |

Q4: How can I effectively remove endotoxins from my protein samples? Several chromatographic methods leverage the negative charge and hydrophobic properties of endotoxins. The choice of method depends on your protein's characteristics.

| Method | Principle | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Chromatography (e.g., Poly(ε-lysine) ligands) | Cationic ligands selectively bind endotoxins under physiological conditions [28]. | High selectivity for LPS without binding most proteins. |

| Immobilized Metal-Affinity Chromatography (IMAC) with detergent | His-tagged protein binds to Ni-NTA; endotoxin is washed away with non-ionic detergent before protein elution [29]. | Effective for His-tagged proteins; can achieve <0.2 EU/mg [29]. |

| Anion Exchange Chromatography | Binds negatively charged endotoxins at high pH, allowing protein to flow through [28]. | Requires pH-mediated destabilization of endotoxin structure. |

| Cation Exchange Chromatography | Binds positively charged protein at low pH (~4), allowing endotoxin to flow through [28]. | Suitable for basic proteins. |

| Novel Affinity Adsorbents (e.g., Factor C domains) | Uses immobilised LPS-binding domains (e.g., CES3) from horseshoe crab Factor C to specifically capture endotoxins [10]. | High specificity; can be produced in an LPS-free plant system [10]. |

Q5: How do I validate my endotoxin testing method to ensure accurate results? For the LAL test, a Positive Product Control (PPC) recovery validation is essential to rule out that your sample matrix is not inhibiting or enhancing the enzymatic reaction, which would lead to false negatives or positives [8]. This involves:

- Spiked Sample: Testing your sample spiked with a known amount of endotoxin standard (e.g., 0.5 EU/mL).

- Calculation: The measured endotoxin in the spiked sample must be within 50-200% of the known spike value to prove the test is valid for your product [30] [8]. For quantitative kinetic methods, this validation is built into each assay run [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Endotoxin Levels After Standard Affinity Purification

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Endotoxins are co-purifying with your protein via strong hydrophobic or charge interactions.

- Solution: Incorporate a specific endotoxin removal step. Use an affinity adsorbent like poly(ε-lysine)-cellulose beads (e.g., Cellufine ETclean) in a spin-column format. This can be done after your primary purification. Optimize the buffer conditions (ionic strength and pH) to maximize endotoxin binding while keeping your protein in solution [28].

- Solution: For His-tagged proteins, add a wash step with a non-ionic detergent (e.g., Triton X-114) to the IMAC column before elution. This protocol has been shown to reduce endotoxin to 0.2 EU/mg with nearly 100% protein recovery [29].

Cause: Your starting material (cell lysate) has an extremely high endotoxin load, overwhelming the purification system.

- Solution: Focus on prevention. Optimize fermentation to minimize bacterial lysis. If possible, use a purification tag that allows for purification under denaturing conditions (e.g., urea), which dissociates endotoxin aggregates and facilitates their removal [31].

Problem: Inconsistent Endotoxin Measurements with LAL Assay

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Matrix interference – components in your sample buffer are inhibiting or enhancing the LAL reaction.

Cause: The standard curve is invalid or the assay is not performed under controlled conditions.

- Solution: Ensure the correlation coefficient (r) of your standard curve is ≥ 0.980 [30]. Run the assay in a controlled environment and use validated, endotoxin-free labware. Routinely qualify your pipettes and microplate reader.

Experimental Protocols & Data Visualization

Protocol 1: Validated Kinetic Chromogenic LAL Test

This protocol is based on methods validated according to ICH Q2 and EU Pharmacopoeia guidelines for use as a limit test for impurities [30].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- LAL Reagent: Kinetic chromogenic LAL test kit (e.g., Pyrotell-T, EndoZyme).

- Endotoxin Standard: Certified reference standard endotoxin.

- Endotoxin-Free Water: Used for reconstitution and blanks.

Methodology:

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the LAL reagent and endotoxin standard according to the manufacturer's instructions using endotoxin-free water.

- Standard Curve: Prepare at least three different concentrations of endotoxin standard in duplicate to generate a standard curve.

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the protein sample appropriately in endotoxin-free water. Include a positive product control (PPC) by spiking an aliquot of the diluted sample with the middle concentration of the standard curve (e.g., 0.5 EU/mL).

- Incubation: Add 100 µL of each standard, blank, unspiked sample, and PPC sample to a pyrogen-free microtiter plate. Add 100 µL of LAL reagent to each well.

- Measurement: Immediately place the plate in a pre-warmed microplate reader at 37°C. Measure the absorbance or fluorescence continuously (kinetic mode) for at least 90 minutes.

- Analysis: Calculate the standard curve using a non-linear regression model. The correlation coefficient must be ≥ 0.980. The time of signal onset (reaction time) is inversely proportional to the endotoxin concentration. The endotoxin concentration in the samples is calculated by comparing their reaction times to the standard curve. The PPC recovery must be between 50% and 200% for the test to be valid [30] [8].

Protocol 2: Endotoxin Depletion Using Affinity Adsorption

This protocol uses affinity matrices to selectively bind and remove endotoxins from protein solutions [28] [10].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Affinity Matrix: Poly(ε-lysine)-cellulose beads (e.g., Cellufine ETclean) or Factor C domain (CES3)-immobilized cellulose beads.

- Binding/Wash Buffer: Physiological buffer (e.g., 20mM Tris, 150mM NaCl, pH 7.4). The ionic strength (µ) is critical for selectivity and should be optimized [28].

- Sterile, Endotoxin-Free Column or Spin Units.

Methodology:

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the affinity column or spin cartridge with 5-10 column volumes (CV) of your selected binding buffer.

- Sample Preparation: Adjust your protein sample's buffer to match the binding buffer using dialysis or desalting. Ensure the pH and ionic strength are within the optimal range for endotoxin binding and protein stability (e.g., µ = 0.05-0.4) [28].

- Loading: Load the prepared protein sample onto the equilibrated column. Collect the flow-through.

- Washing: Wash the column with 5-10 CV of binding buffer to recover any remaining protein. Combine the flow-through and wash fractions.

- Analysis: The combined protein-containing fraction should now have reduced endotoxin levels. Concentrate the protein if necessary and measure both protein concentration and endotoxin levels (see Protocol 1) to determine the specific activity (EU/mg).

Endotoxin Removal and Control Methods: A Practical Guide for Laboratory and Production

In recombinant protein research, controlling bioburden—the population of viable microorganisms on or in a product or material—is fundamental to preventing endotoxin contamination [32]. Endotoxins, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, are potent pyrogens that can trigger severe inflammatory responses and compromise research integrity and patient safety [33] [34]. This technical support center provides a strategic framework for upstream bioburden control, offering detailed protocols, troubleshooting guides, and FAQs to help researchers safeguard their cell culture and fermentation processes.

Core Concepts: Bioburden and Endotoxins

What is Bioburden?

Bioburden refers to the total number of viable microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, fungi, and mold) present on a surface, in a substance, or within a material before sterilization [32] [35]. In upstream bioprocessing, this includes contaminants potentially introduced via raw materials, equipment, the environment, and personnel. Controlling bioburden is critical because it is the primary source of endotoxins; when Gram-negative bacteria die or lyse, they release these toxic, heat-stable molecules into the process stream [32] [34].

Bioburden vs. Endotoxin Testing

It is essential to distinguish between bioburden and endotoxin testing, as they evaluate different quality attributes. The table below summarizes their key differences:

Table 1: Key Differences Between Bioburden and Endotoxin Testing

| Attribute | Bioburden | Endotoxin |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Total number of viable microorganisms [33] | Toxic substances (LPS) in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria [33] |

| Measurement | Colony-forming units (CFU) [33] | Endotoxin Units (EU) [33] |

| Origin | Air, water, raw materials, personnel [32] [33] | Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., E. coli, Pseudomonas) [33] |

| Health Impact | Indicates contamination risk; can cause product spoilage [33] | Causes fever, inflammation, septic shock [33] [34] |

| Testing Methods | Membrane filtration, direct plate method [35] | Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay, recombinant Factor C (rFC) assay [33] |

Strategic Prevention Framework

A proactive, multi-layered approach is the most effective way to minimize bioburden and subsequent endotoxin contamination.

Source Control

- Raw Materials: Audit suppliers to ensure they exercise documented control over bioburden and endotoxin levels [34]. Test high-risk materials, such as those of natural origin or with high water content.

- Water Systems: Implement rigorous validation and control for water generation and distribution systems, as water is a common source of Gram-negative bacteria and biofilm formation [34].

- Personnel: Provide comprehensive training on aseptic techniques, hygiene, and proper gowning procedures to minimize contamination from operators [32].

Process and Filtration Controls

Sterile filtration is a cornerstone of upstream bioburden control. A multi-stage filtration strategy protects the bioreactor and downstream processes.

Upstream Filtration Strategy for Bioburden Control

- Prefiltration: Uses depth filters (e.g., polypropylene or glass fiber fleece) to remove coarse particles and protect downstream filters. This is ideal for clarifying complex or viscous feedstreams [36].

- Bioburden Reduction: Acts as a pre-sterilization filter to lower the microbial load, protecting the final sterilizing-grade filter and extending its lifespan [37] [36].

- Sterilizing-Grade Filtration: A 0.2 µm membrane filter that serves as the final barrier, ensuring 100% bacteria retention for aseptically added fluids [37].

Environmental and Sanitation Controls

- Cleanroom Management: Maintain controlled environments with advanced air filtration (e.g., HEPA) to minimize airborne contamination [32]. Implement rigorous cleaning and disinfection procedures for all equipment and surfaces [32] [34].

- Endotoxin-Specific Cleaning: Use cleaning tools scientifically proven to remove and retain sub-micron endotoxin debris to prevent cross-contamination [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Bioburden and Endotoxin Control

| Item | Function | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Prefilters | Removes coarse particles and colloids to protect and extend the life of final filters [36]. | High dirt-holding capacity. e.g., Sartopure PP3 (polypropylene fleece), Sartopure GF Plus (charged glass fiber) [36]. |

| Bioburden Reduction Filters | Reduces microbial load in fluids before the final sterilizing-grade filter [37] [36]. | Typically 0.1-0.2 µm pore size. e.g., Sartoguard PES (dual-layer PES membrane) [36]. |

| Sterilizing-Grade Filters | Provides a final sterile barrier with 100% bacteria retention for aseptically added fluids [37]. | 0.2 µm pore size. e.g., PPS filters (hydrophilic, dual-layer membrane) [37]. |

| Water Purification Systems | Produces high-purity water to prevent the introduction of microbes and endotoxins via water [34]. | Systems designed to control biofilm formation in generation and distribution loops. |

| LAL/rFC Reagents | Detects and quantifies endotoxin levels in process samples and final products [33]. | Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) or recombinant Factor C (rFC) for highly sensitive endotoxin testing. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: My process fluid has a very high particle load, and my sterilizing filters are clogging too quickly. What can I do? A: Implement a robust prefiltration strategy. Using a series of depth filters with progressively smaller pore sizes (e.g., starting with a 1.2 µm filter and moving to a 0.65 µm filter) can remove the bulk of the particles and colloids. This protects the more expensive sterilizing-grade filter, reduces change-out frequency, and lowers overall costs [37] [36].

Q: I need to filter a sensitive protein solution. How can I reduce bioburden without losing my product? A: For sensitive biologics like proteins, a bioburden reduction filter with low protein-binding properties is recommended. Filters made of modified Polyethersulfone (PES) are often suitable. It is critical to perform a compatibility and yield study with your specific product during process development to select the optimal filter that minimizes adsorption while effectively reducing microbial load [36].

Q: Our endotoxin tests are failing, but our bioburden results are low. Why is this happening? A: This discrepancy is possible. Bioburden testing only detects viable microorganisms, while endotoxins are stable toxins released from dead Gram-negative bacteria [33]. Your process may be effectively killing bacteria (e.g., via a biocide) but failing to remove the endotoxins they have already released. Investigate sources of Gram-negative bacteria in your water systems, raw materials, and dead legs in process equipment where biofilms can form [34].

Q: Is it necessary to perform both bioburden and endotoxin testing? A: Yes, for a comprehensive contamination control strategy, both are often required. Bioburden testing is typically performed on non-sterile samples as part of validation and periodic monitoring to ensure sterilization processes are effective. Bacterial endotoxin testing is required on a lot-by-lot basis for parenteral products or devices labeled as "non-pyrogenic" to ensure they are safe for patient use [33].

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Bioburden Control

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Consistently High Bioburden in Cell Culture Media | - Contaminated raw materials.- Inadequate sterilization of media or feed tanks.- Biofilm in water system or transfer lines. | - Audit and test raw material suppliers [34].- Validate thermal or filter sterilization cycles.- Increase sanitization frequency of water systems and process equipment [34]. |

| Unexpected Spike in Endotoxin Levels | - Breakdown in aseptic technique.- Gram-negative biofilm dislodged from equipment.- Compromised sterile filter. | - Retrain personnel on aseptic practices [32].- Inspect and clean equipment for biofilm hotspots [34].- Perform integrity testing on sterilizing-grade filters. |

| Rapid Fouling of Sterilizing Filters | - High particulate load in feed fluid.- Inadequate or missing prefiltration step. | - Add or optimize a prefilter train for gradual particle removal [37] [36].- Analyze fluid composition to select the optimal prefilter media (e.g., fleece for high capacity, membrane for precise retention) [36]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Validating a Bioburden Testing Method for a Fluid

This protocol ensures your bioburden testing method accurately recovers microorganisms from your process fluid.

- Sample Preparation: Use a sterile lot of your process fluid (e.g., culture media or buffer).

- Inoculation: Inoculate the fluid with a known, low concentration (e.g., 10-100 CFU) of standard organisms, such as Bacillus atrophaeus spores (aerobic) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Gram-negative) [33].

- Extraction & Enumeration: Process the inoculated sample according to your chosen method (e.g., membrane filtration). Culture the filters and enumerate the recovered colonies.

- Calculation: Calculate the method's recovery efficiency by comparing the number of recovered organisms to the number in the original inoculum.

- Recovery Efficiency (%) = (Number of CFU Recovered / Number of CFU Inoculated) x 100

- Validation Criterion: A recovery rate of ≥50% is often considered acceptable, demonstrating that the method does not inhibit microbial growth and provides a valid count [33].

Protocol: Routine Environmental Monitoring for Bioburden

Regular monitoring of the manufacturing environment is crucial for proactive contamination control [35].

- Surface Monitoring: Use contact plates (RODAC plates) containing a general nutrient agar (like Tryptic Soy Agar) to sample critical surfaces (e.g., bioreactor ports, workbenches) after processing.

- Air Monitoring: Use an active air sampler to draw a measured volume of air from the critical zone (e.g., near the fluid addition port) onto an agar plate.

- Incubation: Incubate the plates as per guidelines (e.g., 20-25°C for 5-7 days for fungi and 30-35°C for 3-5 days for bacteria) [35].

- Data Interpretation: Count the colonies and compare them to established alert and action limits. Investigate any breaches of action limits to identify and eliminate the contamination source.

Effective upstream bioburden control in cell culture and fermentation is not a single action but a continuous, multi-layered strategy. It integrates rigorous source control, a well-designed filtration train, disciplined environmental monitoring, and thorough testing. By adopting the preventative measures, troubleshooting guides, and protocols outlined in this technical support center, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly mitigate the risks of bioburden and endotoxin contamination, thereby ensuring the safety, quality, and success of their recombinant protein research and production.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key mechanisms of ultrafiltration and size exclusion chromatography for endotoxin separation?

- Ultrafiltration (UF) relies on size-based exclusion using membranes with a specific molecular weight cutoff (MWCO). Endotoxin aggregates (>100 kDa) are retained while smaller proteins pass through [9] [38].

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) separates molecules based on their hydrodynamic volume and how they partition between the mobile phase and the pores of the resin. Larger molecules, like endotoxin micelles, elute first, while smaller molecules elute later [39].

FAQ 2: When should I choose ultrafiltration over size exclusion chromatography? The choice depends on your sample characteristics and process goals. The following table compares the core features of each method:

| Feature | Ultrafiltration (UF) | Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Size-based sieving through a membrane [9] | Size-based partitioning into resin pores [39] |

| Endotoxin Removal Efficiency | 28.9% to 99.8% [9] | Varies; can be limited by aggregate size [39] |

| Best Suited For | Small peptides and APIs significantly smaller than endotoxin aggregates [38] | Separating proteins from larger endotoxin micellar structures [39] |

| Process Scalability | Highly scalable for large volumes [9] | Scalable, but resin volume and flow rates can be limiting |

| Key Limitations | Low filtration rates with viscous products; ineffective if protein size is similar to endotoxins [38] | Limited resolution if endotoxins form small aggregates or bind to proteins [39] |

FAQ 3: Why is my endotoxin removal efficiency low with a 10 kDa ultrafiltration membrane? Low efficiency can occur due to:

- Protein Concentration: High protein concentrations can shield endotoxins or increase solution viscosity [9].

- Endotoxin Aggregation State: Endotoxins can form vesicles of 300-1000 kDa, but may also exist in smaller forms that pass through the membrane [38].

- Molecular Interactions: Stable endotoxin-protein complexes can form, preventing their separation by size alone [40] [38].

- Detergent Interference: The presence of detergents can disrupt endotoxin aggregates, reducing their effective size [9].

FAQ 4: Can these methods handle all my protein samples? No. These physical methods are highly dependent on the size difference between your target protein and the endotoxin aggregates. They are generally ineffective for proteins with a molecular weight close to or larger than that of the endotoxin micelles [38]. Furthermore, if endotoxins form stable, bound complexes with your protein of interest, charge-based or affinity methods may be required [39] [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Endotoxin Clearance in Ultrafiltration

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Incorrect Membrane Molecular Weight Cutoff (MWCO)

- Solution: Use a membrane with a 100 kDa MWCO, which is more effective for retaining large endotoxin aggregates while allowing smaller proteins to pass through [9].

- Preventive Action: Characterize the aggregate size of endotoxins in your specific solution buffer, as it can vary.

Cause: Low Transmembrane Pressure or Flow Rate

- Solution: For Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF), optimize the cross-flow rate and transmembrane pressure to maintain a stable flux without forming a polarized gel layer that can foul the membrane.

- Diagnostic Step: Monitor the filtrate flow rate. A declining rate indicates membrane fouling or concentration polarization.

Cause: Endotoxin-Protein Complexation

Problem 2: Inadequate Separation in Size Exclusion Chromatography

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Protein and Endoxin Co-Elution

- Solution: Ensure the resin pore size is appropriate. Smaller pores enhance the separation of smaller proteins from larger endotoxin structures via size exclusion [9].

- Alternative Approach: If co-elution persists, consider using an anion-exchange resin in void-exclusion mode (VEAX), where the protein is repelled and elutes first while the negatively charged endotoxin binds to the resin [41].

Cause: Sample Volume is Too Large

- Solution: The sample load volume should typically be 1-5% of the total column volume to achieve good resolution. Overloading will lead to poor separation.

- Corrective Action: Concentrate your sample and use a higher protein concentration with a smaller injection volume.

Cause: Endotoxin Aggregates are Disrupted

- Solution: Avoid solutions with high concentrations of detergents or solvents that can break down large endotoxin micelles into smaller monomers that co-elute with the target protein [39].

- Preventive Action: Use buffers that promote endotoxin aggregation, such as those containing divalent cations like Mg²⁺.

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Endotoxin Removal via Ultrafiltration

This protocol outlines the steps for endotoxin removal from a recombinant protein solution using a 100 kDa molecular weight cutoff membrane [9] [38].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| 100 kDa MWCO Ultrafiltration Device | The core unit for size-based separation; can be a stirred cell or tangential flow filter. |

| Protein Buffer (e.g., PBS) | A compatible, low-endotoxin buffer to maintain protein stability and function. |

| Triton X-114 Detergent | A nonionic surfactant used to pre-treat samples and dissociate endotoxin-protein complexes [9]. |

| LAL Reagent Kit | For quantifying endotoxin levels before and after processing to validate removal efficiency [9]. |

Methodology:

- Sample Pre-treatment (Optional but Recommended): If endotoxin-protein complexes are suspected, add Triton X-114 to the protein sample to a final concentration of 1% (v/v). Incubate at 4°C for 30 minutes with constant stirring to create a homogeneous solution [9].

- System Setup and Equilibration: Assemble the ultrafiltration device according to the manufacturer's instructions. Pre-rinse the membrane with several volumes of endotoxin-free water, followed by equilibration with your protein buffer.

- Sample Processing: Load the protein solution into the ultrafiltration device. For stirred cells, apply gentle pressure (e.g., nitrogen gas) with constant stirring. For Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF), establish the recommended cross-flow rate and transmembrane pressure.

- Diafiltration: To enhance endotoxin removal, continuously add fresh buffer to the sample retentate at the same rate as the filtrate is being removed. This process dilutes and removes endotoxins from the retentate. A diafiltration volume of 5-10 is typical.

- Retentate Recovery: Once processing is complete, recover the concentrated protein solution from the retentate.

- Endotoxin Quantification: Use the LAL assay to measure endotoxin levels in both the initial sample and the final retentate to determine the removal efficiency [9].

Workflow Diagram: Ultrafiltration Process

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in the ultrafiltration process for endotoxin removal.

Decision Pathway: Selecting a Physical Separation Method

This flowchart provides a logical framework for deciding whether ultrafiltration or size exclusion is the most appropriate technique for a given experimental context.

FAQs on Endotoxin Removal in Recombinant Protein Research

Fundamental Concepts

1. What are endotoxins and why must they be removed from recombinant protein preparations? Endotoxins, also known as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), are toxic components found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria like E. coli, a common host for recombinant protein expression. They can bind to biomolecules during production and, if introduced into the bloodstream of a mammalian host, trigger severe immune responses such as inflammation or septic shock. Their removal is therefore critical to ensure the safety, reliability, and validity of proteins used in research, diagnostics, and therapeutics [9].

2. How do Ion Exchange, Affinity, and Multimodal Chromatography function in endotoxin removal? These techniques exploit different properties of endotoxins for separation:

- Ion Exchange Chromatography (IEX): Primarily uses charge differences. Endotoxins have a very low isoelectric point (pI~2), making them strongly negatively charged at most chromatographic pH levels. In Anion Exchange Chromatography (AEC), endotoxins bind to the positively charged resin, allowing the target protein to flow through if it is positively charged under the same conditions [9].

- Affinity Chromatography: Utilizes highly specific ligands immobilized on a solid support to bind endotoxins. Common ligands include Polymyxin B, histidine, or other specialized molecules that capture LPS. The target protein passes through while endotoxins remain bound to the ligand [42] [9].

- Multimodal Chromatography: Also known as Mixed-Mode Chromatography, it combines multiple interaction mechanisms, such as ion exchange and hydrophobic interaction, within a single resin. This provides more opportunities for effective separation, which is particularly valuable for challenging purifications, such as those involving proteins with low pIs or complex impurities [43].

Method Selection and Optimization

3. How do I choose the right chromatographic method for my protein? Selection depends on the properties of your target protein and the required purity. The table below compares the core methods.

Comparison of Endotoxin Removal Methods [9]

| Method | Efficiency | Specificity | Cost | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Chromatography | High | High | High | Expensive ligands; may require specific elution conditions |

| Ion Exchange Chromatography | High | Medium | Medium | Sensitive to pH and salt conditions; relies on charge differences |

| Phase Separation (Triton X-114) | Moderate | Low | Low | Potential for trace detergent residues in final product |

| Ultrafiltration | Moderate | Low | Low | Ineffective at removing small endotoxin aggregates |

| Adsorption (e.g., Activated Carbon) | High | Medium | Medium | Non-selective; can cause significant product loss |

For acidic proteins (low pI), anion exchange chromatography is often highly effective because the protein will not bind the resin, while endotoxins will. For sensitive proteins, a weak anion exchanger multimodal resin may be preferable as it can reduce binding strength and improve yield for low pI proteins [43]. When the primary goal is high specificity, affinity chromatography is the best choice, though at a higher cost [9].

4. What are key factors for optimizing an Ion Exchange Chromatography run?

- Selectivity and Capacity: The resin's selectivity for target ions and its exchange capacity are paramount. Capacity is influenced by pore size, surface area, and functional group density [44].

- Chemical Compatibility: Ensure the resin is compatible with your solution's pH, temperature, and concentration to avoid degradation [44].

- Binding and Elution Conditions: Optimize buffer pH and ionic strength to ensure endotoxins bind while your target protein does not. A common elution strategy employs a increasing salt gradient to disrupt ionic interactions [45].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

5. My protein recovery is low after Affinity Chromatography. What could be wrong? Low recovery in affinity purification can stem from several issues:

- Harsh Elution Conditions: Acidic elution buffers (e.g., glycine-HCl, pH 2.5-3.0) commonly used for elution can denature some proteins. Immediately neutralize collected fractions with a Tris buffer [45]. Consider testing milder elution conditions like competitive ligands or changes in ionic strength.

- Ligand Specificity: The affinity ligand (e.g., Polymyxin B) might also have some non-specific binding to your target protein. Re-evaluate the ligand's specificity or switch to a different purification mode [42] [19].

- Non-Specific Binding: Ensure your wash buffers contain low levels of detergent or appropriate salt to minimize non-specific ionic binding without eluting your target [45].

6. I'm seeing peak tailing and broadening in my Ion Exchange chromatogram. How can I fix this? Peak shape issues in IEX often relate to column packing or binding kinetics.

- Secondary Interactions: Tailing can arise from undesirable interactions between the protein and active sites on the resin. Try using a different resin with a more inert stationary phase [46].

- Column Overload: If the mass of the loaded sample is too high, it can lead to tailing or fronting. Reduce the injection volume or dilute your sample [46].

- Poor Column Packing or Voids: If all peaks are tailing, it may indicate a physical problem with the column, such as a void at the inlet. Examine the inlet frit, use a guard column, or consider replacing the column [46].

7. Endotoxin levels are still too high after a single purification step. What should I do? Achieving sufficient endotoxin clearance often requires a multi-faceted approach.

- Combine Orthogonal Methods: Use methods based on different principles sequentially. For example, a common and effective strategy is to use Triton X-114 phase separation followed by anion exchange chromatography [42] [9].

- Optimize and Repeat: Some methods, like Triton X-114 separation, can be repeated 1-2 times on the same sample to further reduce endotoxin levels [9].