Proteostasis as a Master Regulator of Molecular Evolvability: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

This article explores the critical and evolving paradigm that the cellular proteostasis network is a central modulator of molecular evolution.

Proteostasis as a Master Regulator of Molecular Evolvability: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

Abstract

This article explores the critical and evolving paradigm that the cellular proteostasis network is a central modulator of molecular evolution. We examine the mechanistic bases by which chaperones, quality control systems, and degradation pathways influence protein evolvability—shaping stability-epistasis relationships, managing mutational robustness, and governing the exploration of protein sequence space. Targeting an audience of researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis integrates foundational concepts with methodological approaches, troubleshooting insights, and comparative validation studies. The discussion extends to the therapeutic exploitation of proteostasis networks in pathogens and the potential for targeting evolvability in treating aging-related and neurodegenerative diseases, providing a comprehensive resource for understanding this fundamental driver of adaptive evolution.

The Proteostasis Network: Architect of the Genotype-Phenotype Landscape

Cellular protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, is a fundamental biological process that maintains the cellular proteome in a functional and balanced state [1]. The proteostasis network (PN) is the integrated cellular system responsible for controlling the synthesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation of proteins from their synthesis to their destruction [2] [1]. This exquisite balance is crucial for all cellular functions, and its disruption—a state known as dysproteostasis—is implicated in a wide spectrum of human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, cancer, and metabolic syndromes [1] [3]. The PN achieves this remarkable feat through the coordinated activity of approximately 3,000 genes that encode its various components [2]. These components function cooperatively across three interconnected core processes: protein synthesis, protein folding and trafficking, and protein degradation [2]. Understanding the architecture and function of the PN provides not only critical insights into disease pathogenesis but also reveals how proteostasis influences broader biological phenomena, including molecular evolvability—the capacity of biological systems to generate heritable phenotypic variation [4].

Core Components of the Proteostasis Network

The proteostasis network encompasses a sophisticated array of molecular machinery organized into specific functional and compartmentalized branches. The table below summarizes the core components and their primary functions.

Table 1: Core Components and Functions of the Proteostasis Network

| Component Category | Key Elements | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Chaperones | Heat shock proteins (HSPs), Nucleoplasmin, GroE [1] | Assist in proper protein folding, prevent aggregation, refold misfolded proteins, and aid in protein transport [1]. |

| Folding Enzymes | Enzymes facilitating disulfide bond formation, SUMOylation, glycosylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, palmitoylation [2] | Catalyze and ensure correct post-translational modifications essential for protein structure and function [2]. |

| Degradation Machinery | Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS), Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway (ALP) [2] [3] | Identify and degrade misfolded, damaged, or excess proteins [2] [3]. |

| Regulatory Systems | Unfolded Protein Response (UPR), Heat Shock Response (HSR) [2] [1] | Surveillance mechanisms that detect proteostatic imbalance and activate compensatory pathways to restore homeostasis [2] [1]. |

| Organelle-Specific Branches | Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) proteostasis, Mitochondrial proteostasis, Nuclear proteostasis, Extracellular proteostasis [2] | Maintain protein quality control within specific subcellular compartments [2]. |

These components do not operate in isolation but function as a cooperative network to provide comprehensive surveillance of proteome integrity [2]. This integrated functionality is particularly critical in specialized cells like neurons, which are long-lived, post-mitotic, and have high metabolic demands, making them exceptionally vulnerable to proteostasis decline [2].

Proteostasis Network Pathways and Disease Signatures

Large-scale analyses of the PN across human diseases have revealed that its disruption follows distinct, patterns. These "proteostasis signatures" are characteristic patterns of change in the PN associated with specific disease states [3] [5]. Research has identified three generalizable proteostasis states that can discriminate between major disease types [3] [5]:

Table 2: Proteostasis States in Major Disease Categories

| Proteostasis State | Key Pathway Perturbations | Associated Disease Types |

|---|---|---|

| State 1 | Significant UPS perturbation; limited extracellular proteostasis involvement [3] [5] | Cancers [3] [5] |

| State 2 | Extensive perturbation of both UPS and extracellular proteostasis [3] [5] | Neurodegenerative Diseases (e.g., Alzheimer's, Parkinson's) [3] [5] |

| State 3 | Distinctive deregulation of extracellular proteostasis; limited UPS involvement [3] [5] | Autoimmune, Endocrine, Cardiovascular, Reproductive, and Respiratory diseases [3] [5] |

Quantitative profiling shows that proteostasis proteins comprise a substantial portion (25-36%) of disease gene sets in cancers and neurodegenerative diseases (30-35%) [3] [5]. At the pathway level, the Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway (ALP) and proteostasis regulation are consistently over-represented across all diseases [3]. Furthermore, the temporal dynamics of PN failure differ significantly between disease types; proteostasis perturbations occur progressively in neurodegenerative diseases but manifest early in cancers [3].

Experimental Methodologies for Proteostasis Analysis

The complex, interconnected nature of the PN demands a multifaceted experimental approach. The following workflow visualizes a core strategy integrating multiple cutting-edge techniques to assess PN function.

Diagram 1: Integrated PN analysis workflow.

Core B: Sensors and Tools for Proteostasis Analysis

This methodology focuses on developing and deploying fluorescent-based molecular sensors and reporters to quantitatively measure the activity of different PN arms, such as chaperone function and ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) activity [6]. These sensors are expressed in model organisms or cell cultures. The core experimental protocol involves:

- Sensor Implementation: Introduce genetically-encoded fluorescence-based reporters for specific PN components (e.g., chaperone machinery, UPS) into the model system [6].

- Longitudinal Imaging: Utilize multiplexed, longitudinal single-cell imaging platforms to track reporter signals over time [6].

- Quantitative Analysis: Apply deep learning and quantitative image analysis to extract data on PN activity from the imaging results, providing a dynamic view of proteostasis events [6].

Core C: Global Proteostasis Network Assessment by TMT-MS3 Proteomics

This approach provides a global, unbiased snapshot of the proteome and the PN's status [6]. The detailed protocol is as follows:

- Sample Preparation: Lyse cells or tissues from the experimental model. Reduce, alkylate, and digest proteins into peptides.

- Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) Labeling: Label peptides from different experimental conditions (up to 10 samples per run) with isobaric TMT reagents. This allows for multiplexed analysis [6].

- Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Separate the pooled, labeled peptides using liquid chromatography. Analyze them using a tandem mass spectrometry method with a third MS3 scan (TMT-MS3) to accurately quantify peptide abundance [6].

- Data Analysis: Quantify the levels of thousands of proteins, including over 1,000 specific PN components (chaperones, proteasome subunits, etc.). This fingerprint reveals the state of the PN and identifies changes in protein pathways under different experimental conditions [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Proteostasis Network Analysis

| Research Reagent / Tool | Core Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence-Based PN Reporters [6] | Molecular sensors that quantify the activity of specific PN arms (e.g., chaperones, UPS) in live cells. | Real-time, longitudinal assessment of proteostasis capacity in response to genetic or chemical perturbations [6]. |

| Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) Reagents [6] | Isobaric chemical labels for multiplexed quantitative proteomics. | Enable simultaneous quantification of protein levels from multiple experimental conditions in a single TMT-MS3 mass spectrometry run, providing a global view of the proteome and PN [6]. |

| Small Molecule Proteostasis Regulators (PRs) [6] | Pharmacological agents that target specific PN nodes. | Used to test PN function by modulating pathways like the Heat Shock Response (HSR), Unfolded Protein Response (UPR), proteasome, or autophagy [6]. |

| Longitudinal Single-Cell Imaging Platforms [6] | Advanced microscopy systems for tracking cells over time. | Allows for monitoring the fate of individual cells expressing PN reporters, crucial for understanding heterogeneity in proteostasis failure and aggregation [6]. |

The Proteostasis Network as a Modulator of Molecular Evolvability

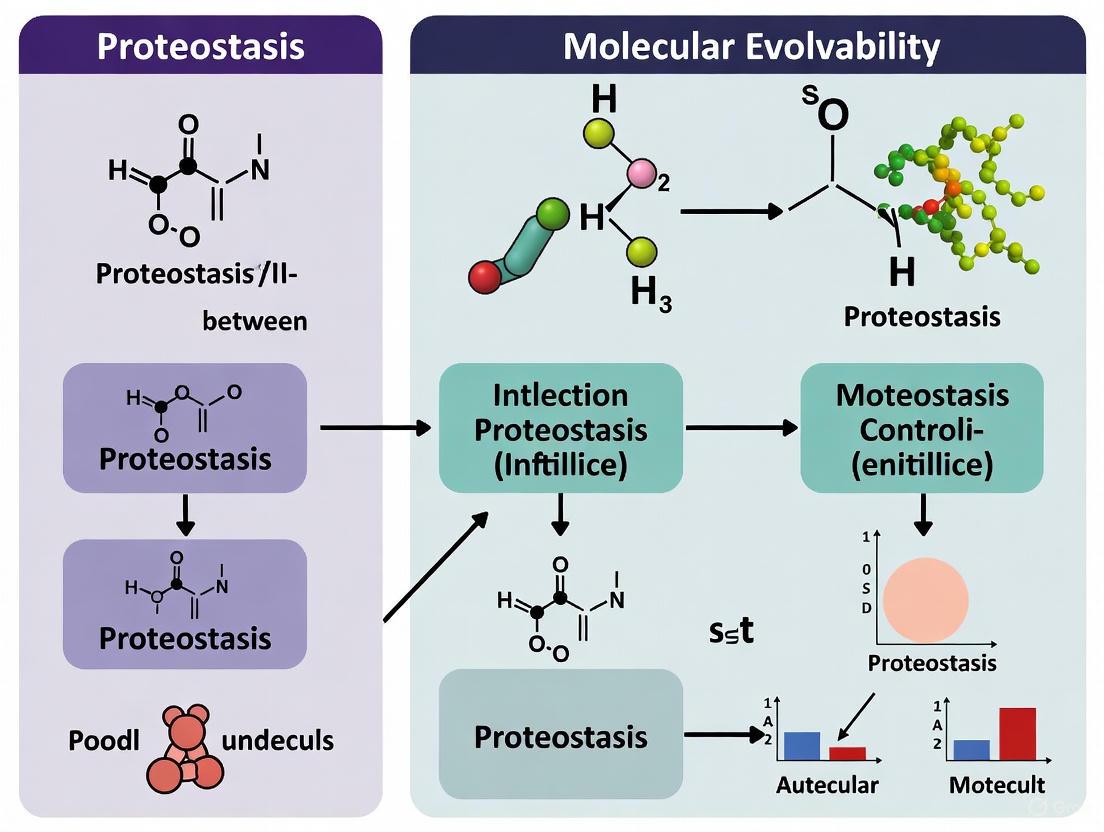

The PN plays a profound role beyond cellular maintenance, acting as a master modulator of molecular evolution [4]. The relationship between proteostasis and evolvability can be visualized as a cycle where the PN shapes the exploration of genetic and phenotypic space.

Diagram 2: PN modulates molecular evolvability.

The PN, comprising chaperones and proteases, influences evolutionary processes through several key mechanisms. It affects epistasis—the interaction between genes—by buffering or amplifying the phenotypic effects of mutations, thereby shaping the fitness landscape [4]. Furthermore, the PN enhances evolvability by allowing the accumulation of genetic variation that might otherwise be deleterious; these hidden variations can be revealed under conditions of proteostatic stress, providing a source of potential adaptations [4]. Finally, by managing the folding and stability of novel protein variants, the PN influences the navigability of protein space, determining which evolutionary paths are accessible to an organism and constraining or enabling the exploration of new functional protein sequences [4]. This perspective is strongly supported by studies in bacterial systems, which demonstrate that the protein quality control network participates in vital cellular processes and fundamentally influences organismal development and evolution [4].

The proteostasis network is a complex, integrated system essential for cellular viability, organized around the core functions of synthesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation of proteins. Its comprehensive mapping and the subsequent emergence of proteostasis signatures are revolutionizing our understanding of disease pathogenesis, revealing distinct patterns of failure in conditions like cancer and neurodegenerative disorders. The experimental toolbox for probing the PN—encompassing sophisticated reporters, global proteomics, and pharmacological regulators—enables detailed dissection of its components and functions. Beyond its role in health and disease, the PN is a critical factor in evolutionary biology, shaping the relationship between genotype and phenotype and modulating molecular evolvability. A deep understanding of the proteostasis network therefore provides a unified framework for innovating therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring cellular balance and offers fundamental insights into the mechanisms of molecular evolution.

Cellular protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, represents a fundamental biological paradigm where a delicate balance between protein synthesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation maintains a functional proteome [1]. The proteostasis network—an integrated system of molecular chaperones, folding enzymes, and degradation machineries—ensures that polypeptide chains acquire correct three-dimensional structures essential for biological function [1]. Within this network, molecular chaperones constitute a critical defense mechanism against protein misfolding and aggregation, both under normal physiological conditions and in response to proteotoxic stresses [7] [8]. Beyond their canonical roles in protein folding and quality control, emerging evidence reveals that molecular chaperones, particularly Hsp70, Hsp60, and Hsp90, function as buffers of genetic variation, shaping the relationship between genotypic variation and phenotypic expression [9] [10].

This buffering capacity arises from the ability of chaperones to stabilize partially folded, conformational states of proteins, thereby mitigating the deleterious structural consequences of genetic mutations [10]. By acting as "evolutionary capacitors," these chaperone systems can reveal cryptic genetic variation under conditions of cellular stress or when the chaperone network is compromised, potentially accelerating evolutionary processes [10]. This review comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms whereby Hsp70, Hsp60, and Hsp90 systems buffer genetic variation, explores experimental approaches for investigating this phenomenon, and discusses the implications for disease pathogenesis and therapeutic development within the broader context of proteostasis and molecular evolvability research.

Structural and Functional Basis of Chaperone-Mediated Buffering

The Proteostasis Network and Molecular Chaperone Classification

Molecular chaperones comprise a diverse group of proteins classified primarily by molecular weight and shared structural features. The major chaperone families include Hsp100, Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp60, Hsp40, and small heat shock proteins (sHSPs), each with distinct but complementary functions in maintaining proteostasis [7] [8]. These chaperones collectively form a sophisticated network that oversees the entire protein lifecycle—from nascent chain folding to refolding of metastable proteins, assembly of macromolecular complexes, and ultimately, targeted degradation of irreversibly damaged proteins [1] [7].

Most chaperones function as ATP-dependent foldases (e.g., Hsp60, Hsp70, Hsp90) that actively promote folding through ATP-regulated binding and release cycles, while others, particularly sHSPs, act as ATP-independent holdases that prevent aggregation by binding unfolding clients [7] [8]. This functional specialization enables the proteostasis network to manage a diverse array of folding challenges, with different chaperone families often working cooperatively in sequential folding pathways or chaperone relays [11] [12].

Table 1: Major Molecular Chaperone Families and Their Core Functions

| Chaperone Family | Major Members | ATP-Dependence | Primary Functions | Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSP90 | HSP90α, HSP90β, GRP94, TRAP1 | ATP-dependent | Folding of metastable regulators (kinases, steroid receptors); conformational buffering | Cytosol, ER, Mitochondria |

| HSP70 | HSPA1A, HSPA8, HSPA5, HSPA9 | ATP-dependent | De novo folding, refolding, translocation, disaggregation | Cytosol, Nucleus, ER, Mitochondria |

| HSP60 | HSP60, TRiC/CCT | ATP-dependent | Folding of small proteins in sequestered chambers | Mitochondria, Cytosol |

| HSP40 | DNAJA, DNAJB, DNAJC | ATP-independent | Co-chaperone for HSP70; regulates ATPase activity | Various compartments |

| sHSPs | HSPB1-B10 | ATP-independent | Holdases; prevent aggregation under stress | Cytosol, Nucleus, Mitochondria |

Structural Mechanisms of Genetic Variation Buffering

The capacity of chaperones to buffer genetic variation stems from their fundamental molecular mechanisms. Chaperones recognize and interact with exposed hydrophobic patches typically buried within properly folded native structures [1] [8]. Mutations frequently destabilize protein fold, increasing the exposure of these hydrophobic segments and thereby enhancing chaperone binding. This interaction can prevent degradation or aggregation of variant proteins, allowing them to retain partial or complete function despite their structural imperfections [9] [10].

Hsp90 exemplifies this buffering capacity through its specialized role as a conformational buffer for metastable signaling proteins, particularly kinases and transcription factors [9] [10]. These "client" proteins exist in a dynamic equilibrium between folded and partially unfolded states. Hsp90 stabilizes these conformers through its ATP-regulated chaperone cycle, which involves large-scale conformational changes and coordinated interactions with numerous co-chaperones [8] [10]. When genetic variation reduces the intrinsic stability of client proteins, their dependence on Hsp90 increases correspondingly, creating a system wherein the chaperone masks the phenotypic consequences of mutations [9].

Similarly, the Hsp70 system buffers genetic variation through its interactions with nascent chains and newly synthesized proteins [11]. Hsp70 binding can stabilize folding intermediates, allowing more time for proper acquisition of native structure even when mutations slow folding kinetics or reduce stability [7] [11]. The Hsp60 chaperonin system, particularly the TRiC complex in the cytosol, provides an encapsulated folding environment that physically separates folding proteins from the crowded cellular milieu, offering another layer of protection against mutational destabilization [7] [8].

Diagram 1: Molecular chaperones buffer genetic variation by stabilizing proteins with reduced stability due to mutations. When chaperone capacity is exceeded under stress, previously hidden phenotypic consequences are revealed.

The Hsp90 Buffering System: A Paradigm for Evolutionary Capacitance

Hsp90 as a Global Modifier of Genotype-Phenotype Relationships

Hsp90 represents the best-characterized molecular buffer of genetic variation, functioning as a global modifier that shapes the manifestations of mutations across diverse biological systems [9] [10]. The extensive client portfolio of Hsp90—encompassing numerous kinases, transcription factors, and other regulatory proteins—positions it uniquely to influence broad phenotypic landscapes [10]. Systems-level analyses reveal that Hsp90 occupies a central position in protein-protein interaction networks, interacting physically or genetically with over 10% of the yeast proteome, which explains its disproportionate impact on phenotypic expression [10].

The buffering capacity of Hsp90 was first demonstrated in Drosophila melanogaster, where pharmacological inhibition or genetic compromise of Hsp90 function revealed previously cryptic morphological variation [10]. Subsequent research established this evolutionary capacitor function across diverse taxa, including plants, fungi, and mammals [9] [10]. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, for instance, reducing Hsp90 activity unmasked hundreds of previously silent genetic variants affecting growth and morphology [10].

Molecular Mechanism of Hsp90-Mediated Buffering

The molecular basis of Hsp90's buffering function lies in its ATP-dependent chaperone cycle and its interactions with co-chaperones that regulate client protein folding and stability [8]. Hsp90 clients are typically metastable proteins that exist in a dynamic equilibrium between folded and partially unfolded states. Under normal conditions, Hsp90 stabilizes these clients through repeated binding and release cycles, utilizing ATP hydrolysis to drive conformational changes that promote native structure acquisition or maintenance [8] [10].

When mutations reduce the intrinsic stability of client proteins, their dependence on Hsp90 increases correspondingly. This relationship was elegantly demonstrated in human genetic diseases such as Fanconi anemia, where the phenotypic severity of FANCA mutations correlates inversely with preferential engagement by Hsp90 (versus Hsp70) [9]. Mutant FANCA proteins predominantly bound by Hsp90 retained significant function, whereas those primarily engaging Hsp70 were severely compromised [9]. This client-specific buffering extends to numerous disease-associated variants, suggesting a general mechanism whereby Hsp90 shapes disease expressivity and penetrance.

Table 2: Experimental Evidence for Chaperone Buffering of Genetic Variation

| Experimental System | Chaperone System | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fanconi anemia mutants | HSP90 vs. HSP70 | Mutant FANCA engaged by HSP90 retained function; HSP70-bound mutants were severely compromised | [9] |

| Natural genetic variation in yeast | HSP90 | ~20% of natural variants showed HSP90-buffering; half involved non-coding regulatory variants | [10] |

| Cancer evolution | HSP90 | Oncogenic mutants (e.g., v-Src) show heightened HSP90 dependence; inhibition abrogates transformation | [10] |

| Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency | GRP94 (ER HSP90) | Spatial covariance profiling revealed GRP94 role in managing aggregation-prone variants | [13] |

| Morphological evolution in Drosophila | HSP90 | Pharmacological inhibition revealed cryptic morphological variation | [10] |

Hsp70 and Hsp60 Systems in Genetic Variation Management

Hsp70: Integration Point in Proteostasis Networking

The Hsp70 system represents a central integration point within the proteostasis network, functioning both independently and cooperatively with other chaperone systems to buffer genetic variation [7] [11]. Hsp70 interacts with nascent polypeptide chains during synthesis, facilitating co-translational folding—a critical point where mutations first exert their effects on protein biogenesis [7] [11]. The Hsp70 cycle is regulated by co-chaperones including Hsp40 (which stimulates ATPase activity) and nucleotide exchange factors (which promote ADP release and substrate binding) [7] [8].

Hsp70's buffering capacity stems from its ability to prevent aggregation of folding intermediates and promote proper folding through iterative substrate binding and release cycles [11]. This function becomes particularly important for variant proteins with slowed folding kinetics or reduced stability. The Hsp70 system also collaborates with Hsp90 in a well-characterized chaperone relay, wherein Hsp70 initially engages clients before transferring them to Hsp90 for final maturation [11] [12]. This cooperative buffering extends the range of genetic variation that can be effectively managed by the proteostasis network.

Hsp60/Chaperonins: Encapsulated Folding Environments

The Hsp60 chaperonin system, represented by GroEL/GroES in bacteria and TRiC/CCT in eukaryotes, provides a physically segregated folding environment that buffers genetic variation through distinct mechanisms [7] [8]. These large, barrel-shaped complexes encapsulate folding proteins within a central cavity, isolating them from the crowded cellular environment and potential aggregation partners [7]. This encapsulated folding is particularly important for proteins with complex folding pathways or those prone to aggregation.

The eukaryotic TRiC complex exhibits additional specialization, folding specific classes of proteins including actin, tubulin, and cell cycle regulators [8]. Mutations in these essential proteins often increase their dependence on TRiC-mediated folding, creating another layer of chaperone-mediated buffering. The compartmentalized nature of the chaperonin system means its buffering capacity is inherently limited by the availability of functional complexes, creating potential bottlenecks in proteostasis capacity [7] [8].

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Chaperone Buffering

Systematic Mapping of Chaperone-Client Interactions

Comprehensive understanding of chaperone buffering requires systematic approaches to map client interactions and their dependence on chaperone function. Quantitative proteomic methods, including affinity purification coupled with mass spectrometry and thermal proximity coaggregation, have enabled global profiling of chaperone-client relationships under varying conditions [10]. These approaches reveal that approximately 20% of natural genetic variants in yeast show buffering by Hsp90, with surprisingly half involving non-coding regulatory variants rather than protein-coding changes [10].

Spatial covariance profiling using Gaussian process regression-based machine learning represents another powerful approach for investigating chaperone functions in managing genetic variation [13]. This method has elucidated the role of GRP94, the endoplasmic reticulum Hsp90 paralog, in managing alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency by profiling residue-by-residue folding consequences of sequence variants [13].

Assessing Buffering Capacity Through Chaperone Perturbation

Direct assessment of chaperone buffering capacity typically involves comparing phenotypic expression under normal versus compromised chaperone function [9] [10]. Pharmacological inhibitors (e.g., geldanamycin derivatives for Hsp90), genetic manipulation to reduce chaperone expression, or environmental stress that titrates chaperone capacity all serve to reveal previously buffered phenotypic variation [9] [10].

In the cancer context, this approach has demonstrated that oncogenic mutants often exhibit heightened dependence on Hsp90, with inhibition exacerbating their instability and functional impairment [10]. Similarly, in Fanconi anemia, reducing Hsp90's buffering capacity with inhibitors or febrile temperatures destabilized buffered FANCA mutants, exacerbating disease-related cellular phenotypes [9].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for investigating chaperone buffering of genetic variation, combining interaction mapping, computational modeling, and functional perturbation approaches.

Research Reagent Solutions for Chaperone Buffering Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Chaperone Buffering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSP90 Inhibitors | Geldanamycin, 17-AAG, Radicicol | Perturb HSP90 function to reveal buffered variants | Varying bioavailability, toxicity, and specificity profiles |

| HSP70 Inhibitors | VER-155008, MAL3-101 | Assess HSP70 contribution to buffering | Limited specificity; often affect multiple HSP70 isoforms |

| Chaperone Expression Constructs | Wild-type and mutant HSP90, HSP70, HSP60 | Genetic manipulation of chaperone function | Consider isoform-specific effects and co-chaperone requirements |

| Client Protein Reporters | Mutant FANCA, v-Src, TP53 variants | Quantitative assessment of chaperone-dependent stability | Choose clients with established chaperone dependence |

| Proteostasis Stressors | Heat shock, proteasome inhibitors, oxidative stress | Titrate chaperone capacity without direct inhibition | Induce pleiotropic effects beyond chaperone network |

| Interaction Mapping Tools | Co-immunoprecipitation antibodies, BioID systems | Characterize chaperone-client relationships | Distinguish direct vs. indirect interactions |

Implications for Disease and Therapeutic Development

Chaperone Buffering in Human Disease Expressivity

The capacity of molecular chaperones to buffer genetic variation has profound implications for understanding variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance in human genetic diseases [9]. By stabilizing mutant proteins that would otherwise be degraded or form toxic aggregates, chaperones can ameliorate disease severity in a mutation-specific manner [9]. This buffering relationship explains why identical mutations can produce dramatically different clinical outcomes depending on individual variations in chaperone expression, activity, or ongoing cellular stresses [9] [10].

In Fanconi anemia, the correlation between mutant FANCA engagement by Hsp90 (versus Hsp70) and disease severity provides a molecular basis for clinical heterogeneity [9]. Similarly, in neurodegenerative diseases characterized by protein aggregation, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, chaperone capacity influences the onset and progression of pathology by managing the proteotoxicity of misfolding-prone proteins [1] [13].

Cancer Evolution and Therapeutic Resistance

Cancer cells particularly exploit chaperone buffering to manage the proteotoxic stress associated with oncogenic mutations and rapid proliferation [1] [10]. Many oncoproteins (e.g., mutant p53, BCR-ABL, HER2) are inherently unstable Hsp90 clients that require continuous chaperone support for function [10]. This dependence creates a therapeutic window wherein Hsp90 inhibition simultaneously compromises multiple oncogenic pathways, explaining the extensive investigation of Hsp90 inhibitors in oncology [8] [10].

The chaperone network also influences cancer evolution by buffering the effects of genetic diversity within tumors. By stabilizing otherwise dysfunctional mutant proteins, chaperones increase the pool of genetic variation available for selection during tumor progression and therapeutic resistance development [10]. This relationship positions chaperones as key modulators of cancer evolvability, with implications for understanding and predicting resistance mechanisms.

Therapeutic Targeting of Chaperone Buffering

Strategic targeting of chaperone buffering capacity represents a promising approach for modulating the phenotypic expression of genetic diseases [8] [14]. Traditional strategies have focused on direct inhibition of chaperone ATPase activity, particularly for Hsp90, with multiple candidates entering clinical trials [8]. More sophisticated approaches now target specific co-chaperone interactions or allosteric regulatory sites to achieve greater selectivity for particular client subsets or tissue types [8].

An alternative strategy involves selective disruption of buffering for disease-driving mutant proteins while preserving chaperone functions for essential cellular clients [9] [8]. This approach requires detailed understanding of how specific mutations alter chaperone dependency—information that can be obtained through spatial covariance profiling and other quantitative methods [13]. For loss-of-function diseases where excessive degradation of partially functional mutant proteins contributes to pathogenesis, enhancing rather than inhibiting chaperone buffering may represent a beneficial therapeutic strategy [9] [14].

Molecular chaperones function as integrated buffers of genetic variation, shaping the relationship between genotype and phenotype across biological scales from single proteins to entire organisms. The Hsp90, Hsp70, and Hsp60 systems employ distinct but complementary mechanisms to manage mutational effects, stabilizing variant proteins that would otherwise be functionally compromised. This buffering capacity influences evolutionary processes, disease expression, and therapeutic responses, positioning chaperones as central modulators of phenotypic diversity.

Future research directions include developing more comprehensive maps of chaperone-client relationships across genetic backgrounds and environmental conditions, elucidating how chaperone networks themselves evolve in response to proteostatic challenges, and designing therapeutic strategies that selectively modulate buffering for specific disease-associated variants. As the spatial and temporal regulation of chaperone networks becomes better understood, so too will our ability to harness their buffering capacity for therapeutic benefit in the numerous diseases characterized by proteostasis disruption.

Proteostasis and the Management of Protein Folding Energy Landscapes

Protein folding is a fundamental biological process governed by the energy landscape theory, which describes the pathway from nascent polypeptide chains to functional three-dimensional structures. This journey is meticulously regulated by the proteostasis network (PN), an integrated cellular system comprising molecular chaperones, folding enzymes, and degradation machineries. Disruptions in proteostasis lead to a pathological state known as dysproteostasis, resulting from an imbalance in the protein folding energy landscape. This imbalance is implicated in numerous human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders and cancer. This technical guide explores the core principles of protein folding energy landscapes, their physiological management by the proteostasis network, and the pathological consequences of their collapse. We provide a comprehensive analysis of current experimental and computational methodologies for studying these landscapes, along with quantitative data and detailed protocols. The content is framed within the broader context of molecular evolvability, highlighting how the inherent properties of energy landscapes facilitate protein evolution and adaptation. This resource is intended for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand and target proteostasis mechanisms for therapeutic innovation.

The energy landscape theory provides a conceptual framework for understanding protein folding, framing it as a funnel-guided process where the native state occupies the global free energy minimum [1]. The topography of this landscape—its ruggedness, the depth of its minima, and the height of its barriers—dictates the efficiency and fidelity of folding. A smooth, funnel-like landscape favors rapid folding to the native state, while a rugged landscape, characterized by kinetic traps from non-native interactions, can lead to misfolding and aggregation [1] [15].

Cellular proteostasis is the biological system responsible for managing this energy landscape. It ensures that proteins acquire their native conformation, maintain it, and are degraded when damaged, thereby preserving proteome functionality. The PN achieves this through a network of molecular chaperones, the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), the autophagy-lysosomal pathway (ALP), and stress response pathways like the heat shock response (HSR) and the unfolded protein response (UPR) [1] [16] [6]. The relationship between the energy landscape and the proteostasis network is symbiotic: the landscape defines the thermodynamic and kinetic challenges of folding, while the proteostasis network provides the tools to navigate it successfully. From an evolutionary perspective, the shape of a protein's energy landscape is a key determinant of its evolvability. Landscapes that are robust yet permit sequence variation allow for the exploration of new functions without catastrophic loss of structure, enabling molecular evolution.

Core Principles of the Protein Folding Energy Landscape

The folding of a protein is not a simple linear path but a probabilistic journey across a multidimensional energy surface. The following principles are central to the energy landscape theory:

- The Folding Funnel: This concept illustrates that the number of possible conformations decreases as the protein approaches its native state. The width represents conformational entropy, and the depth represents the energy. The funnel guides the polypeptide chain toward the native structure without requiring an exhaustive search of all possible conformations, thus resolving Levinthal's paradox [1].

- Ruggedness and Kinetic Traps: A perfectly smooth funnel is an idealization. Real landscapes are rugged, with local energy minima corresponding to metastable folding intermediates or misfolded states. These kinetic traps can slow folding or lead to off-pathway aggregation [1] [15].

- Metastable States and Fluctuations: Even in their native state, proteins exist as ensembles of conformations, continuously fluctuating around the native structure. These rare, higher-energy states are crucial for function, as they can facilitate interactions with partners or enable allosteric regulation. However, they also represent potential entry points to misfolding pathways and can influence protein aggregation and immunogenicity [17].

Table 1: Key Features of the Protein Folding Energy Landscape

| Feature | Description | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Global Minimum | The lowest free energy state, corresponding to the native conformation. | Determines the stable, functional structure of the protein. |

| Folding Funnel | A funnel-shaped topography that guides the polypeptide toward the native state. | Enables rapid and efficient folding without an exhaustive conformational search. |

| Ruggedness | The presence of local minima and barriers on the landscape. | Can lead to kinetic trapping, folding intermediates, and misfolding. |

| Metastable States | Higher-energy conformations that are transiently populated. | Crucial for protein function, dynamics, and interaction, but can be precursors to aggregation. |

Modern research, leveraging large-scale experimental analyses, has revealed that conformational fluctuations are not uniform across a protein structure. Studies on 5,778 protein domains have shown that hidden variation in conformational fluctuations exists even between sequences sharing the same fold and global stability. These fluctuations often involve entire secondary structural elements that have lower stability than the overall fold [17]. This modular view of stability, with less stable "hotspots" within an otherwise stable architecture, has critical implications for understanding how mutations far from active sites can disrupt function and for the intelligent design of stabilized proteins.

The Proteostasis Network: Managing the Landscape

The cellular proteostasis network functions as a comprehensive management system for the protein folding energy landscape, preventing proteins from becoming trapped in non-productive states and responding to proteostatic stress.

Key Components of the Proteostasis Network

The following diagram illustrates the core components of the Proteostasis Network and their functional relationships:

Diagram: The Core Components of the Proteostasis Network and Their Interactions

The Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) Signaling

The UPR is a critical signaling cascade activated by the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). It aims to restore ER proteostasis by reducing the load of new proteins and enhancing the folding and degradation capacity.

Diagram: The Three Branches of the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR)

Quantitative proteomic studies using data-independent acquisition (DIA) LC-MS/MS have enabled branch-specific monitoring of UPR activation by quantifying effector proteins downstream of ATF6, IRE1/XBP1s, and PERK [16]. This approach allows for an unbiased, systems-level evaluation of UPR dynamics in complex systems, such as aging neurons and glia.

Table 2: Experimental Models for Studying Proteostasis and Energy Landscapes

| Experimental System | Key Readouts | Applications and Insights |

|---|---|---|

| Dual-Species Neuron-Glia Co-culture [16] | Species-specific proteomics (DIA LC-MS/MS); UPR branch activation; protein trafficking. | Cell-type-specific aging responses; neuron-glia crosstalk in proteostasis collapse. |

| Intact Protein Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) [17] | Conformational fluctuation energies; stability of secondary structural elements. | Large-scale discovery of protein energy landscapes; identification of low-stability segments. |

| Machine-Learned Coarse-Grained (CG) Molecular Dynamics [15] | Folding/unfolding free energy landscapes; metastable states; root-mean-square deviation/fluctuation. | Predicts protein dynamics orders of magnitude faster than all-atom MD; explores folding mechanisms. |

Methodologies for Analyzing Energy Landscapes and Proteostasis

Protocol: Large-Scale Analysis of Energy Landscapes via HDX-MS

This protocol is adapted from the large-scale study of 5,778 protein domains to map conformational fluctuations [17].

- Sample Preparation: Express and purify the target protein domains (e.g., libraries of domains 28-64 amino acids in length). Ensure samples are in a stable, native-like buffer condition.

- Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange (HDX): Dilute the protein sample into a D₂O-based exchange buffer. Allow exchange to proceed for a series of predetermined time points (e.g., from seconds to hours) at a controlled temperature and pH.

- Quenching and Digestion: At each time point, withdraw an aliquot and quench the exchange reaction by lowering the pH and temperature. Pass the quenched sample through an immobilized pepsin column for rapid digestion into peptides.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Inject the digested peptides into a liquid chromatography system coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer. Use rapid separation to minimize back-exchange.

- Data Processing: Process the MS data using specialized software (e.g., HDExaminer) to identify peptides and calculate their deuterium incorporation at each time point.

- Energy Landscape Modeling: The deuterium uptake kinetics for each peptide are used as a proxy for local stability. Calculate the free energy of opening (ΔG°op) for structural segments by fitting the exchange data to a two-state model (closed vs. open). This reveals site-resolved conformational fluctuations and identifies low-stability segments.

Protocol: Branch-Specific UPR Activation Analysis via DIA Proteomics

This protocol details how to quantify the activation of all three UPR branches in a complex biological sample, such as a cell culture or tissue [16].

- Model System Setup: Establish a relevant model system (e.g., human neuronal cells, treated with ER stress inducers like tunicamycin or thapsigargin). Include appropriate controls.

- Sample Lysis and Protein Preparation: Lyse cells in a denaturing buffer. Reduce, alkylate, and digest the protein extract using trypsin.

- Liquid Chromatography and Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Analyze the resulting peptides using a data-independent acquisition (DIA) method on a high-resolution mass spectrometer. In DIA mode, the instrument fragments all ions within sequential, pre-defined isolation windows, generating a comprehensive map of fragment ions.

- Spectral Library Search and Peptide Quantification: Process the DIA data using software such as DIA-NN. Search the data against a project-specific spectral library built from data-dependent acquisition (DDA) runs of the same samples or a predicted library from a sequence database.

- UPR Branch Activation Scoring: For each UPR branch (ATF6, IRE1/XBP1s, PERK), quantify the abundance of a curated set of known downstream effector proteins. Aggregate the abundance changes of these effector sets to generate a composite score representing the activation level of each specific branch.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Proteostasis and Energy Landscape Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Proteostasis Network Reporters [6] | Fluorescence-based sensors to quantify the activity of different PN components (e.g., chaperone capacity, UPS activity). | Real-time monitoring of PN changes in live cells during aging or drug treatment. |

| Multiplexed Longitudinal Single-Cell Imaging Platform [6] | A platform for tracking protein aggregation, autophagy, and cell fate over time in individual live cells. | Understanding the heterogeneity of cellular responses to proteotoxic stress. |

| TMT-MS3 Proteomics [6] | A highly accurate, multiplexed global proteomics method for simultaneously quantifying protein levels and post-translational modifications across 10+ samples. | Providing a systems-wide "fingerprint" of the PN state under different experimental conditions. |

| Machine-Learned Coarse-Grained (CG) Force Field [15] | A computationally efficient simulation model trained on all-atom data to predict protein dynamics and folding free energies. | Exploring the folding landscapes of large proteins and protein mutants where all-atom MD is computationally prohibitive. |

| Species-Specific Peptide Detection (DIA LC-MS/MS) [16] | A computational and experimental pipeline to differentiate proteomes in co-culture systems without physical separation. | Studying cell-type-specific proteostasis dynamics in neuron-glia co-cultures. |

Implications for Molecular Evolvability and Therapeutic Innovation

The management of protein folding energy landscapes by the proteostasis network is not merely a homeostatic function; it is a fundamental enabler of molecular evolvability. The rugged, yet funneled, nature of energy landscapes allows proteins to explore sequence space. Slightly destabilizing mutations can populate cryptic, higher-energy conformations that can be selected for new functions, a process facilitated by chaperones that can buffer against destabilizing mutations. Furthermore, the PN itself is adaptable—stress response pathways can be induced to alter the cellular environment, allowing otherwise destabilized variants to fold and function. This capacity for phenotypic plasticity is a key substrate for evolution.

Therapeutically, targeting the proteostasis network offers a powerful strategy for treating diseases of dysproteostasis. Strategies include:

- Chaperone Modulators: Small molecules that enhance the function of specific molecular chaperones, such as HSP70 or HSP90, to promote the refolding of misfolded proteins or triage them for degradation [1] [6].

- Proteostasis Pathway Activators: Pharmacologic agents that activate stress-responsive signaling pathways, such as the HSR or UPR, to globally enhance the cell's folding and degradation capacity. This approach aims to upregulate all components of a PN compartment in the correct stoichiometry [1] [6].

- Stabilizer Compounds: Molecules that bind to specific proteins and stabilize their native state, effectively deepening the global minimum on their energy landscape. This is a promising approach for diseases caused by loss-of-function mutations that destabilize proteins [1].

- Degradation Pathway Enhancers: Activators of the ubiquitin-proteasome system or the autophagy-lysosomal pathway to clear irreversibly aggregated proteins, a hallmark of many neurodegenerative diseases [6].

In conclusion, the interplay between the intrinsic protein energy landscape and the extrinsic cellular proteostasis network defines the folding, function, and evolvability of the proteome. Advanced computational models and multiplexed experimental techniques are now providing an unprecedented view of these landscapes, opening new frontiers for understanding fundamental biology and developing transformative therapies for a wide range of human diseases.

The central dogma of molecular biology outlines the flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA to protein. However, the critical mechanistic link that translates a DNA sequence (genotype) into an observable cellular or organismal function (phenotype) is the proteostasis network—the integrated biological system responsible for synthesizing, folding, trafficking, and degrading proteins. This whitepaper examines the proteostasis network as a fundamental modulator of phenotypic expression, detailing how its regulatory mechanisms influence molecular evolvability, adaptive evolution, and disease pathogenesis. By synthesizing recent advances in proteostasis research, we provide a framework for understanding how perturbations in protein homeostasis create distinct molecular signatures across human diseases and create selective pressures that guide evolutionary trajectories in both microbial and mammalian systems.

The relationship between genotype and phenotype is not linear but is governed by complex, multi-layered cellular processes. Among these, protein homeostasis (proteostasis) serves as the crucial intermediary that determines whether a genetic sequence yields a functional output or a pathological state. The proteostasis network comprises approximately 3,000 genes that encode components of an integrated system encompassing protein synthesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation [2]. This network maintains the functional proteome through collaborative organelle-specific efforts and adaptive stress responses [2].

Recent research has established that proteostasis not only ensures proper protein function but also modulates molecular evolvability—the capacity of proteins to acquire novel functions through mutation and selection [18] [19]. By buffering genetic variations or amplifying their effects, the proteostasis network shapes the adaptive landscape, influencing which mutations yield viable phenotypes and which lead to pathological outcomes [18]. This review examines the proteostasis network as the quintessential link between genotype and phenotype, with particular emphasis on its role in molecular evolution and disease pathogenesis.

The Proteostasis Network Architecture

The proteostasis network represents a sophisticated regulatory system that maintains proteome integrity through compartmentalized and collaborative mechanisms. Its architecture can be conceptualized across three interconnected functional domains and multiple subcellular branches.

Core Functional Domains

The proteostasis network operates through three primary, interconnected processes [2]:

- Protein Synthesis: Regulation of ribosomal translation and co-translational folding

- Protein Folding and Trafficking: Assisted folding by molecular chaperones and transport to cellular destinations

- Protein Degradation: Clearance of misfolded or damaged proteins via specialized pathways

Organelle and Process-Specific Branches

The proteostasis network functions through nine specialized branches that maintain proteome fidelity across cellular compartments [2]:

Table 1: Proteostasis Network Branches and Functions

| Branch | Primary Components | Core Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Translation | Ribosomal proteins, Initiation factors | Synthesis rate control, co-translational folding |

| Nuclear Proteostasis | Nuclear chaperones, SUMOylation machinery | Nuclear protein quality control, DNA-protein interactions |

| Mitochondrial Proteostasis | Mitochondrial HSPs, Lon protease | Energy metabolism protein maintenance |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum | Calnexin, BiP, ERAD machinery | Secretory protein folding, ER stress response |

| Extracellular Proteostasis | Chaperones, Clusterin | Extracellular matrix maintenance |

| Cytonuclear Proteostasis | Nuclear import/export machinery | Nucleocytoplasmic transport |

| Ubiquitin-Proteasome System | E3 ligases, Proteasome | Short-lived protein degradation |

| Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway | Autophagy receptors, Lysosomal enzymes | Aggregate clearance, organelle turnover |

| Proteostasis Regulation | HSF1, NRF2, UPR sensors | Stress response pathway activation |

These branches do not function in isolation but exhibit extensive crosstalk, creating a resilient system for proteome surveillance. For instance, ER stress activates the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR), which coordinates with the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy-lysosome pathway (ALP) to restore equilibrium [2].

Visualization of Proteostasis Network Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture of the proteostasis network and its functional integration:

Proteostasis as a Modulator of Molecular Evolvability

Molecular evolvability refers to the capacity of proteins to explore sequence space and acquire novel functions through mutation and selection. The proteostasis network profoundly influences this process through several biophysical mechanisms.

Proteostatic Buffering and Genetic Robustness

Chaperones and other proteostasis components can buffer the phenotypic effects of mutations, allowing genetic variations to accumulate without immediate fitness consequences [18]. This buffering capacity creates a reservoir of cryptic genetic variation that can be exposed under changing environmental conditions or cellular stress, thereby accelerating adaptation [19]. For example, the chaperone DnaK in E. coli has been identified as a source of mutational robustness, enhancing tolerance to mutations that would otherwise be destabilizing [18].

Protein Stability as an Evolvability Determinant

Protein stability represents a crucial determinant of evolutionary potential. Stable protein folds can tolerate a broader range of mutations while maintaining structural integrity, thereby increasing the probability of acquiring novel functions without loss of native activity [19]. The relationship between stability and evolvability follows a bell-shaped curve: insufficient stability leads to loss of function, while excessive stability may constrain conformational flexibility needed for functional innovation [19].

Quality Control Systems as Evolutionary Gatekeepers

Proteostasis components, particularly proteases like Lon in bacteria, act as evolutionary gatekeepers by selectively degrading mutant proteins with compromised folding [20] [18]. This degradation creates a fitness threshold that mutations must overcome to yield functional phenotypes. In antibiotic resistance evolution, Lon protease degrades mutant dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) variants, directly influencing which genotypic changes result in resistant phenotypes [20].

Table 2: Proteostasis Components and Their Roles in Molecular Evolvability

| Proteostasis Component | Role in Evolvability | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Chaperones | Buffer destabilizing mutations, enable conformational diversity | DnaK in E. coli increases mutational robustness [18] |

| Quality Control Proteases | Filter mutations based on folding competence | Lon protease degrades mutant DHFR variants [20] |

| Ubiquitin-Proteasome System | Regulate abundance of mutant protein species | TRIM21 targets misfolded GABAA receptors [21] |

| Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway | Clear protein aggregates that constrain evolution | Aggregate removal enables exploration of mutational space |

| Stress Response Pathways | Induce proteostasis remodeling under pressure | HSF1 activation expands chaperone capacity |

Case Study: Proteostasis and Antibiotic Resistance Evolution

Research on E. coli adaptation to trimethoprim demonstrates how proteostasis shapes evolutionary trajectories. Resistance typically occurs through mutations that increase dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) expression or reduce drug binding [20]. However, the Lon protease selectively degrades certain mutant DHFR variants, creating a proteostatic constraint on resistance evolution. In Lon-deficient strains, the mutational landscape shifts dramatically, with genomic duplications encompassing folA (encoding DHFR) becoming more frequent [20]. This demonstrates how proteostasis mechanisms determine which genotypic changes successfully yield resistant phenotypes.

The following diagram illustrates the interplay between proteostasis and evolution in antibiotic resistance:

Proteostasis Signatures in Human Disease

When proteostasis fails, the resulting imbalance leads to distinctive molecular patterns called "proteostasis signatures" that characterize specific disease states. Large-scale pan-disease analyses reveal that proteostasis proteins are significantly over-represented in disease-associated gene sets, with particularly strong associations in cancer (25-36%) and neurodegenerative diseases (30-35%) [5] [3].

Distinct Proteostasis States Across Disease Types

Research across 32 human diseases has identified three predominant proteostasis states that differentiate disease mechanisms [5] [3]:

Table 3: Proteostasis States in Major Disease Categories

| Proteostasis State | Key Features | Associated Diseases |

|---|---|---|

| State 1: UPS-Dominant | Significant UPS perturbation, limited extracellular proteostasis involvement | Cancers (multiple types) |

| State 2: Mixed UPS/Extracellular | Extensive perturbation of both UPS and extracellular proteostasis | Neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Huntington's) |

| State 3: Extracellular-Dominant | Distinctive extracellular proteostasis deregulation, limited UPS involvement | Autoimmune, cardiovascular, endocrine, respiratory diseases |

Temporal Dynamics of Proteostasis Collapse

The progression of proteostasis disruption follows distinct temporal patterns across disease types:

- Neurodegenerative diseases: Proteostasis perturbations accumulate progressively throughout disease course [3]

- Cancers: Proteostasis alterations occur early in pathogenesis and are maintained [3]

In neurodegenerative disorders, the accumulation of misfolded proteins like hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau), β-amyloid (Aβ), and α-synuclein slowly overwhelms the UPS and ALP systems, leading to synaptic failure and neuronal dysfunction [2]. Cancer cells, by contrast, actively hijack proteostasis networks—particularly the UPS—to support rapid proliferation and mitigate proteotoxic stress from oncogenic signaling [5] [3].

Experimental Approaches for Proteostasis Research

Quantitative Interactome Proteomics

Systematic identification of proteostasis network components requires advanced proteomic methods. Quantitative immunoprecipitation-tandem mass spectrometry (IP-MS/MS) with Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC) enables mapping of protein interaction networks under different folding conditions [21].

Protocol Summary:

- Generate cells expressing bait proteins (e.g., WT and mutant receptors)

- Culture in SILAC media containing light ([¹²C₆]-Lys/Arg) or heavy ([¹³C₆]-Lys/Arg) isotopes

- Perform immunoprecipitation under native conditions

- Analyze by high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry

- Identify interactors through quantitative comparison of heavy/light ratios

- Validate interactions through co-immunoprecipitation in native tissue

This approach successfully identified 125 interactors for WT GABAA receptor α1 subunits and 105 interactors for misfolding-prone α1(A322D) subunits, with 54 overlapping proteins between the two interactomes [21]. The methodology revealed key proteostasis network components including chaperones, folding enzymes, trafficking factors, and degradation machinery.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Proteostasis Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| SILAC Labeling Kits | Heavy lysine/arginine isotopes | Quantitative interactome profiling [21] |

| Chaperone Inhibitors | HSP90, HSP70 inhibitors | Testing proteostasis buffering capacity |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib | UPS functional assessment |

| Autophagy Modulators | Chloroquine, Rapamycin | ALP pathway interrogation |

| Protein Stability Probes | Thermal shift dyes, Cycloheximide | Protein half-life determination [21] |

| Stress Response Reporters | HSE-luciferase, UPR sensors | Proteostasis network activation |

| Mutant Protein Variants | Misfolding-prone mutants (e.g., GABAA α1-A322D) | Folding capacity assessment [21] |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram outlines a standardized proteomics workflow for proteostasis network analysis:

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The central role of proteostasis in connecting genotype to phenotype offers promising therapeutic avenues for diverse diseases. Several targeted approaches are currently under investigation:

Proteostasis Network Remodeling

- Chaperone modulators: Drugs that enhance specific chaperone functions to stabilize mutant proteins in conformational diseases

- Proteostasis network regulators: Compounds that activate stress response pathways (HSF1, UPR) to boost proteostatic capacity

- Selective protein degradation: Bifunctional molecules that target disease-associated proteins for destruction by the UPS

Disease-Specific Therapeutic Strategies

- Neurodegenerative diseases: Enhance ALP function to clear protein aggregates, or inhibit specific aggregation-prone proteins

- Cancer: Exploit proteostatic vulnerabilities in malignant cells, particularly the high proteotoxic stress from rapid proliferation

- Conformational diseases: Pharmacological chaperones that stabilize correct protein folding and traffic

Understanding the proteostasis signatures of specific diseases will enable more precise therapeutic interventions aimed at restoring proteostatic balance rather than targeting individual proteins [5] [3].

The proteostasis network represents the essential mechanistic link between genotype and phenotype, transforming genetic information into functional proteomic outputs. Through its roles in protein synthesis, folding, and degradation, the proteostasis network shapes molecular evolvability by filtering genetic variations and determining their phenotypic consequences. Distinct proteostasis signatures across human diseases highlight both the vulnerability and adaptability of this system. As research methodologies advance, particularly in quantitative proteomics and network analysis, our understanding of proteostasis will continue to reveal new therapeutic opportunities for restoring balance in disease states. The ongoing characterization of proteostasis networks across tissues, cell types, and pathological conditions will further illuminate this quintessential link in the genotype-to-phenotype relationship.

The integration of protein homeostasis (proteostasis) with evolutionary genetics has revealed fundamental mechanisms shaping protein evolution. This review synthesizes evidence that the cellular proteostasis network (PN) acts as a critical modulator of epistasis—the dependence of mutational effects on genetic background—and thereby influences the accessibility and probability of evolutionary trajectories. We present a mechanistic framework describing how molecular chaperones and other PN components reshape genotype-phenotype maps, analyze quantitative data from experimental studies, and provide detailed methodologies for investigating these relationships. The emerging paradigm positions proteostasis as a central determinant of molecular evolvability, with significant implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

The proteostasis network (PN) comprises the cellular machinery—including chaperones, folding enzymes, and degradation components—that maintains protein homeostasis by ensuring proper protein synthesis, folding, conformational maintenance, and turnover [22] [23]. This network co-evolves with the proteome to manage protein folding in response to environmental stimuli and variation, reflecting the unique stresses that different cells or organisms experience [22]. The PN does not merely passively respond to protein misfolding but actively manages the quinary physiologic state of proteins, dynamically linking their structural features to physiological function [22].

Meanwhile, epistasis—where the effect of a mutation depends on the presence of other mutations—creates historical contingency in evolution by making mutational effects context-dependent [24] [25]. When epistasis occurs within proteins, it can restrict or open evolutionary paths, creating functional interdependencies between amino acid residues [24] [26].

The central thesis of this review is that the PN serves as a master regulator of epistatic interactions by determining the functional expression of genetic variation. Through its capacity to buffer or amplify the phenotypic effects of mutations, the PN shapes the ruggedness of fitness landscapes and controls access to evolutionary trajectories. This framework positions proteostasis as a fundamental mediator of molecular evolvability, with profound implications for understanding evolutionary processes and developing therapeutic interventions for protein-misfolding diseases and cancer.

Theoretical Framework: Proteostasis as an Epistatic Filter

The Quinary State and Protein Evolutionary Landscapes

The concept of the quinary state represents a fifth level of protein structural organization that extends beyond the traditional primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures [22]. This state encompasses the dynamic interactions between a protein and its cellular environment that manage protein folding in response to the metabolic state of the cell and external signaling pathways [22]. The PN actively maintains this quinary state, effectively creating a "cloud" surrounding each protein that is responsive to the local environment to manage protein synthesis, folding, misfolding, and degradation [22].

This management system has profound implications for evolutionary landscapes. In the absence of proteostasis, a protein's function would be determined solely by its amino acid sequence and intrinsic physicochemical properties. The PN introduces an additional layer of regulation that can buffer or expose genetic variation, thereby altering the relationship between genotype and phenotype [22] [1].

Table 1: Proteostasis Network Components and Their Evolutionary Roles

| PN Component | Primary Function | Impact on Evolutionary Trajectories |

|---|---|---|

| HSP70/HSP40 | Co-translational folding; stress response | Buffers deleterious mutations; enables exploration of sequence space |

| HSP90 | Conformational regulation of metastable proteins | Capacitates hidden genetic variation; promotes evolutionary innovation |

| Chaperonins (HSP60) | Folding encapsulation | Enables folding of complex protein domains; mitigates aggregation |

| Small HSPs | ATP-independent aggregation suppression | Provides first-line defense against proteotoxic stress |

| Ubiquitin-Proteasome System | Targeted protein degradation | Removes misfolded proteins; constrains functional space |

| Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway | Bulk protein/organelle degradation | Manages aggregate clearance during severe stress |

Mechanisms of Epistatic Modulation

The PN modulates epistasis through several biophysical mechanisms:

Stability-mediated epistasis: Chaperones can compensate for mutations that reduce protein stability, allowing functionally beneficial but structurally destabilizing mutations to persist [24] [1]. This converts what would be negative epistasis (where combined mutations have stronger deleterious effects than expected) into neutral or even positive epistatic interactions.

Conformation-mediated epistasis: Chaperones like HSP90 can regulate the conformational equilibrium of metastable proteins, enabling mutations that would otherwise lock proteins in non-functional states to instead produce functional diversity [22] [27].

Aggregation-mediated epistasis: By suppressing protein aggregation, chaperones prevent the dominant-negative effects that can occur when misfolded proteins sequester functional ones, thereby altering the epistatic landscape [23] [1].

The following diagram illustrates how the proteostasis network modulates epistatic interactions and evolutionary trajectories:

Quantitative Evidence: Experimental Data and Analysis

High-Order Epistasis in Experimental Evolution

Recent studies have quantified the contributions of different orders of epistasis to evolutionary outcomes. Sailer and Harms (2017) analyzed six experimentally measured genotype-fitness maps, systematically decomposing each map into additive, pairwise, and high-order epistatic components [25]. Their approach involved calculating truncated epistasis models by sequentially setting fifth-, fourth-, third-, and second-order epistatic coefficients to zero, then comparing trajectories through maps with and without high-order epistasis [25].

Table 2: Contributions of Epistatic Orders to Fitness Variation Across Experimental Datasets

| Dataset | Organism/System | Additive Effects (%) | Pairwise Epistasis (%) | High-Order Epistasis (%) | Total Epistasis (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | E. coli (adaptive evolution) | 94.0 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 6.0 |

| II | E. coli (drug resistance) | 85.1 | 9.8 | 5.1 | 14.9 |

| III | A. niger (random mutations) | 79.3 | 12.1 | 8.6 | 20.7 |

| IV | E. coli (adaptive evolution) | 89.5 | 7.2 | 3.3 | 10.5 |

| V | A. niger (random mutations) | 75.4 | 11.5 | 13.1 | 24.6 |

| VI | HIV (drug resistance) | 67.8 | 25.1 | 7.1 | 32.2 |

This analysis revealed that high-order epistasis (interactions between three or more mutations) strongly shapes the accessibility and probability of evolutionary trajectories, despite making relatively small contributions to total fitness variation [25]. The researchers found that high-order epistasis makes it impossible to predict evolutionary trajectories from the individual and paired effects of mutations alone [25].

Proteostasis Capacity Modulates Epistatic Interactions

Bershtein et al. (2015) developed a biosensor-based framework to quantitatively measure latent proteostasis capacity [28]. Their system used barnase mutants with differing folding stabilities to probe chaperone engagement, primarily with HSP70 and HSP90 family proteins [28]. By measuring FRET signals reporting on folded, unfolded, and aggregated states, they could quantify the "holdase" activity of the proteostasis network—its capacity to bind unfolding clients and prevent aggregation [28].

The key finding was that proteostasis capacity acts as a tunable filter for genetic variation. Under conditions of proteostasis stress, mutations that were previously buffered by chaperones become exposed to selection, effectively changing the epistatic relationships between mutations [28]. This provides a mechanistic explanation for how environmental stress can alter evolutionary trajectories by taxing the PN.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Investigation

Combinatorial Deep Mutational Scanning

Purpose: To comprehensively map sequence-function relationships and epistatic interactions across multiple amino acid sites [26].

Detailed Protocol:

Library Design: Select 3-5 critical sites based on structural or functional data. For a transcription factor DNA-binding domain, Starr et al. (2024) focused on four sites critical for DNA recognition [26].

Oligo Library Synthesis: Generate all possible combinations of the 20 amino acids at selected sites using array-based oligonucleotide synthesis. For four sites, this creates 160,000 (20^4) theoretical combinations.

Vector Construction: Clone the oligo pool into an appropriate expression vector using Golden Gate assembly or Gibson assembly. For transcription factors, use a vector that couples protein expression to a reporter gene readout.

Functional Selection:

- Transform the library into the host organism (e.g., yeast for eukaryotic proteins)

- Conduct separate selections for each function of interest (e.g., activation from different DNA response elements)

- Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate functional variants based on reporter expression

Sequencing and Analysis:

- Extract plasmid DNA from sorted populations

- Amplify variant sequences with barcoded primers for multiplexing

- Sequence on an Illumina platform to obtain counts for each variant pre- and post-selection

- Calculate enrichment scores for each variant as log2(frequencypost/frequencypre)

Key Considerations: Include internal controls for normalization, use sufficient library coverage (>50x), and perform biological replicates to assess technical variability.

Biosensor-Based Proteostasis Capacity Measurement

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the latent proteostasis capacity of cells, specifically their "holdase" activity [28].

Detailed Protocol:

Biosensor Construction:

- Create FRET-based biosensors with mTFP1 cp175 and Venus cp173 flanking a folding sensor domain (e.g., barnase)

- Engineer a series of destabilized mutants with predicted ΔG values spanning from -25 kJ/mol (stable) to 1 kJ/mol (unstable)

- Validate folding states in vitro using purified proteins and denaturation curves

Cell Line Generation:

- Stably transduce the biosensor into mammalian cells using lentiviral delivery

- Use low MOI to ensure single-copy integration

- Sort cells to establish homogeneous expression populations

Flow Cytometry Analysis:

- Analyze 50,000-100,000 cells per condition using a high-throughput flow cytometer

- Measure donor fluorescence (mTFP1 excitation/emission) and FRET (sensitized Venus emission)

- Identify distinct populations based on FRET/donor fluorescence slopes

Mathematical Modeling:

- Apply a three-state model (folded, unfolded, aggregated) to interpret FRET distributions

- Use the derived equation to calculate changes in latent chaperone concentration (ΔC): ΔC = [-KdKf(ft - fc)]/(ftfc) - B(ft - fc)(1 + 1/K_f)

- Where Kd is binding affinity, Kf is folding equilibrium, f is fraction folded, and B is barnase concentration

Key Considerations: Include biosensor-free controls, use standardized growth conditions, and validate chaperone engagement through co-immunoprecipitation.

The Proteostasis-Epistasis Signaling Network

The following diagram maps the core signaling pathways through which the proteostasis network detects and responds to proteotoxic stress, thereby modulating the epistatic landscape:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Investigation

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Proteostasis-Epistasis Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biosensor Systems | Barnase FRET biosensors [28], metastable GFP variants | Quantitative measurement of proteostasis capacity and protein folding states |

| Chaperone Modulators | PU-H71 (HSP90 inhibitor) [29], Celastrol (HSF1 activator) [29], Rapamycin (autophagy inducer) [29] | Experimental manipulation of proteostasis network components |

| Epistasis Mapping Tools | Combinatorial DNA libraries [26], ORF assemblies with barcodes | High-throughput mapping of genetic interactions |

| Proteostasis Reporters | HSR-Luciferase, UPR-XBP1 splicing reporters | Monitoring specific proteostasis pathway activation |

| Quantitative Proteomics | TMT/iTRAQ labeling, affinity purification mass spectrometry | System-wide analysis of chaperone-client interactions |

| Model Organisms | C. elegans (e.g., polyQ aggregation models) [29], Yeast (S. cerevisiae) | Genetic screening for proteostasis-epistasis interactions |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The integration of proteostasis biology with evolutionary genetics represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of molecular evolution. The evidence presented establishes that the PN is not merely a housekeeping system but an active modulator of evolutionary processes that shapes the accessibility of evolutionary trajectories through its influence on epistatic interactions.

This synthesis has important implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development. In cancer, tumor cells exploit the PN to manage proteotoxic stress resulting from high mutation loads and rapid proliferation [27]. The diametrically opposed chaperone expression patterns in cancer versus neurodegenerative diseases—with ATP-dependent chaperones induced in cancers but repressed in neurodegeneration—suggest distinct proteostasis strategies in different disease contexts [29]. These patterns represent promising biomarkers for therapeutic targeting.

Future research should focus on several key areas:

- Dynamic mapping of how proteostasis remodeling during differentiation and disease progression alters epistatic landscapes

- Single-cell analysis of proteostasis capacity and its heterogeneity in cell populations

- Computational models that integrate proteostasis parameters into predictions of evolutionary trajectories

- Therapeutic strategies that exploit the PN-epistasis relationship, such as combination therapies that simultaneously target specific oncoproteins and the proteostasis networks that buffer their mutation

The framework presented here positions proteostasis as a central mediator of molecular evolvability, providing both theoretical insights and practical methodologies for advancing this emerging field at the intersection of protein biochemistry, cellular networks, and evolutionary genetics.

Decoding Evolvability: Experimental and Computational Approaches

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) to Probe Historical Proteostasis Interactions

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) has emerged as a powerful phylogenetic method for inferring historical states of biomolecules, enabling direct experimental investigation of ancient protein properties and their interactions within proteostasis networks. This technical guide examines how ASR provides a unique window into the evolutionary relationship between proteostasis and molecular evolvability, allowing researchers to characterize historical protein folding pathways, stability adaptations, and interaction networks. By reconstructing and experimentally validating ancestral proteins, scientists can elucidate how proteostatic mechanisms have shaped the evolution of novel protein functions and constrained evolutionary trajectories. The integration of ASR with modern biophysical techniques creates a robust framework for probing deep historical proteostasis interactions, offering insights critical for protein engineering and therapeutic development.