Protein Quantification Techniques: A Comprehensive Comparative Analysis for Biomedical Research

This article provides a systematic comparison of modern protein quantification techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Protein Quantification Techniques: A Comprehensive Comparative Analysis for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of modern protein quantification techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of colorimetric, chromatographic, and immunoassay methods, detailing their specific applications in contexts like liposomal protein delivery and transmembrane protein analysis. The content addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies to improve accuracy, particularly for challenging samples. Finally, it presents a validated, comparative framework to guide method selection based on sensitivity, specificity, and sample compatibility, empowering robust experimental design in both basic research and clinical applications.

Core Principles of Protein Quantification: Choosing Your Foundation

The Critical Role of Protein Quantification in Standardization and Data Normalization

In biomedical research and drug development, the accuracy of protein quantification is not merely a preliminary step but the very foundation upon which reliable and reproducible scientific conclusions are built. Accurate protein concentration data is critical for a wide range of biological applications, from biochemical assays that assess protein function and the comparison of protein abundances across tissues and species, to the validation of knockdown experiments and the rigorous standards of biologic drug manufacture [1] [2]. Inconsistent or inaccurate quantification introduces significant variability, compromising experimental integrity, hindering the comparison of data across studies, and ultimately impeding scientific and therapeutic progress. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the most prominent protein quantification techniques, evaluating their performance through experimental data to help researchers select the optimal method for standardizing their workflows and ensuring data normalization.

A multitude of protein quantification assays are available to researchers, each with distinct chemistries, advantages, and limitations. The choice of method should be based on factors such as the stage of the drug production process, the goal of the quantification, the individual properties of the protein, and the buffer components involved [2]. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the most common techniques.

Table 1: Key Protein Quantification Methods at a Glance

| Method | Principle of Detection | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis A280 [3] | Absorbance of aromatic residues (Tyr, Trp) at 280 nm. | Quick; no special reagents required; can detect soluble aggregates. | Relies on aromatic residue composition; interfered with by nucleic acids, alcohols, and buffer ions. |

| Bradford Assay [1] [3] | Shift in Coomassie dye absorption upon binding to Arg and aromatic residues. | Quick, easy, and stable; not affected by reducing agents. | Susceptible to protein-protein variation; interfered with by detergents. |

| BCA Assay [1] [3] [4] | Reduction of Cu2+ to Cu+ by peptide bonds, followed by colorimetric detection with BCA. | Less affected by amino acid composition; compatible with detergents. | Interfered with by reducing agents; requires incubation; sensitive to Tyr, Trp, and Cys. |

| Folin-Lowry Assay [3] | Biuret reaction followed by reduction of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent by Tyr and Trp. | Flexible measurement wavelength; stable endpoint. | Incompatible with many common chemicals (EDTA, Tris, reducing agents); nonlinear standard curve. |

| ELISA [1] [5] [6] | Antigen-antibody binding with enzyme-linked colorimetric or fluorescent detection. | High sensitivity and specificity; can quantify specific proteins in complex mixtures. | Can yield false positives/negatives; requires specific antibodies; cannot provide protein size data. |

| Western Blot [6] | Gel electrophoresis separation followed by immunodetection. | Provides molecular weight and modification data; high specificity; confirmatory tool. | Semi-quantitative at best; time-consuming; complex workflow; sensitive to impurities. |

| Kjeldahl Method [3] | Conversion of protein nitrogen to ammonia for quantification. | Precive and reproducible. | Measures total nitrogen, not just protein; requires large sample amounts; impractical for most molecular biology. |

| Calibration-Free Concentration Analysis (CFCA) [7] | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) to measure active protein concentration via binding kinetics. | Directly quantifies functional, active protein; overcomes variability in recombinant protein production. | Requires specialized instrumentation (SPR). |

| Mass Spectrometry [8] [9] | Quantification based on mass-to-charge ratio of peptide ions, often with label-free or isotopic labeling. | High specificity and multiplexing capability; can identify and quantify thousands of proteins. | Expensive instrumentation; complex data analysis; requires expert operation. |

Experimental Data: A Head-to-Head Performance Analysis

Theoretical principles are informative, but empirical data reveals the real-world performance of these methods. A critical study evaluating quantification efficacy on the large transmembrane protein Na,K-ATPase (NKA) demonstrated that conventional colorimetric assays can significantly overestimate protein concentration compared to more specific techniques. The researchers developed an indirect ELISA for NKA and found it provided consistently low variation in subsequent functional assays, whereas the BCA, Bradford, and Lowry methods all overestimated the NKA concentration due to the presence of non-target proteins in the sample [1].

Similarly, in the development of liposomal protein formulations, direct quantification methods were established to accurately measure protein loading. The study validated three techniques—BCA assay, Reverse-Phase HPLC (RP-HPLC), and HPLC coupled with an Evaporative Light Scattering Detector (HPLC-ELSD)—showing all were reliable with linear responses and limits of quantification (LOQ) below 10 µg/mL [4]. The following table synthesizes key quantitative performance metrics from these and other studies.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Protein Quantification Assays

| Method | Linear Range | Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCA Assay | Up to at least 1,500 µg/mL [2] | < 10 µg/mL [4] | Overestimated transmembrane protein concentration vs. ELISA; reliable for direct liposomal quantification [1] [4]. |

| Bradford Assay | Not specified in search results | Not specified in search results | Significantly overestimated transmembrane protein concentration compared to ELISA [1]. |

| Modified Protein-Amidoblack-Complex Precipitation | 100 – 1,750 µg/mL [2] | 40 – 100 µg/mL [2] | Validation showed high tolerance to differing buffer compositions, meeting accuracy criterion of 100 ±5% recovery [2]. |

| RP-HPLC | Linear response with R² = 0.99 [4] | < 10 µg/mL [4] | Reliable for direct quantification of protein loaded in liposomes [4]. |

| HPLC-ELSD | Linear response with R² = 0.99 [4] | < 10 µg/mL [4] | Effective for direct protein quantification in liposomes, especially useful for analytes without a chromophore [4]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Assay Protocol

The BCA assay is a two-step, colorimetric method that relies on the reduction of copper ions by peptide bonds [3] [4].

- Working Principle: Proteins reduce Cu2+ to Cu+ in an alkaline environment (the biuret reaction). The Cu+ ions then react with bicinchoninic acid (BCA) to form a purple-colored complex with strong absorbance at 562 nm [3] [4].

- Procedure:

- Prepare Standard Curve: Dilute a standard protein (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin, BSA) in a series of known concentrations, typically from 25 µg/mL to 2,000 µg/mL, using the same buffer as the unknown samples [10].

- Prepare Working Reagent: Mix the BCA reagents according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Incubate Samples: Add the working reagent to each standard and unknown sample (e.g., a 1:1 ratio) and incubate at 37°C for 15-30 minutes [3] [4].

- Measure Absorbance: Transfer the solutions to a spectrophotometer or plate reader and measure the absorbance at 562 nm.

- Calculate Concentration: Plot a standard curve of absorbance versus concentration for the BSA standards. Use the trendline equation from this curve to calculate the concentration of the unknown samples based on their absorbance [10].

Indirect ELISA Protocol for Specific Quantification

The indirect ELISA is highly specific and ideal for quantifying a target protein like Na,K-ATPase in a heterogeneous mixture [1].

- Working Principle: A capture antibody is immobilized on a plate. The sample containing the target antigen is added, and the antigen binds. A primary antibody specific to the antigen is added, followed by an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody that recognizes the primary. A substrate is added, producing a color change proportional to the amount of antigen [1] [5].

- Procedure:

- Coat the Plate: Adsorb a capture antibody to a 96-well plate by incubation.

- Block the Plate: Add Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or another blocking agent to cover any unsaturated binding sites on the plate [6].

- Add Sample and Standard: Add the protein samples and a dilution series of a standard (e.g., a lyophilized aliquot of the purified target protein) to the wells [1].

- Add Primary Antibody: Introduce a specific primary antibody that binds to the target protein.

- Add Secondary Antibody: Add an enzyme-linked secondary antibody that binds to the primary antibody.

- Add Substrate: Introduce a substrate for the enzyme. The enzyme catalyzes a reaction that produces a colored product.

- Measure Signal: Measure the absorbance or fluorescence of the solution. The intensity is proportional to the amount of target protein bound [1] [6].

- Calculate Concentration: Interpolate the concentration of the unknown samples from the standard curve.

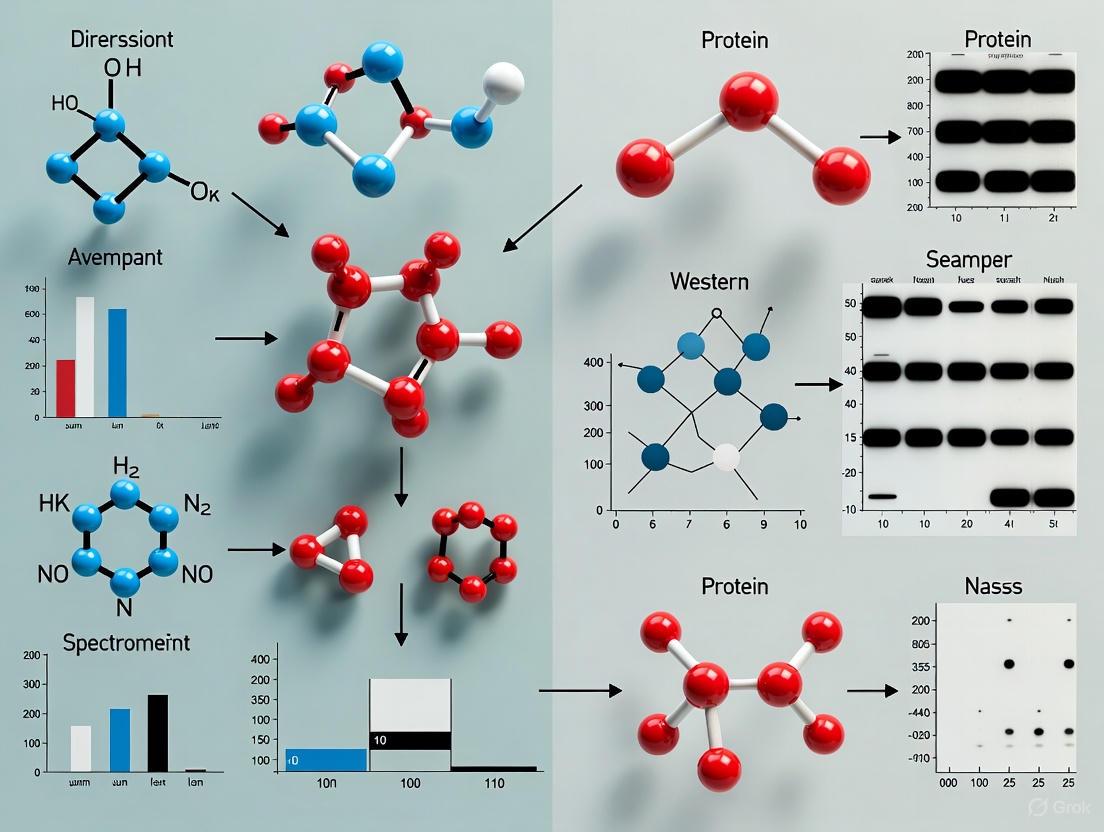

Figure 1: Indirect ELISA Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps for quantifying a specific protein using an indirect ELISA protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful protein quantification requires not only a well-validated method but also high-quality, consistent reagents. The following table details key materials and their functions in these experiments.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Protein Quantification Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Protein (e.g., BSA) [10] [2] | Used to create a standard curve for determining the concentration of unknown samples. | Accuracy is critical. Using a standard traceable to a reference material like NIST is recommended to avoid lot-to-lot variability [2]. |

| Microplates & Readers [6] | 96-well plates enable high-throughput spectrophotometric analysis of many samples at once. | Plates should be checked for homogeneous read-out across all well positions to ensure data consistency [2]. |

| Primary Antibodies [1] | In immunoassays like ELISA, these provide the specificity to detect and quantify the target protein. | Must be validated for specificity and affinity. Storage conditions are critical for maintaining stability [6]. |

| Detection Reagents (BCA, Coomassie Dye) [3] | These chemicals undergo color changes in the presence of protein components, enabling spectrophotometric detection. | Susceptible to interference from buffer components (detergents, reducing agents). Kit selection should match the sample buffer [3]. |

| Chromatography Systems (HPLC) [4] | Provide high-resolution separation and quantification of proteins, often with high sensitivity and specificity. | Methods must be developed and validated for the specific protein and formulation being analyzed [4]. |

Strategic Guidance for Method Selection and Normalization

Choosing the correct quantification method is pivotal for standardization. The following decision pathway can help guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate technique based on their experimental goals and sample type.

Figure 2: Protein Quantification Method Selection. This flowchart assists in selecting the optimal protein quantification method based on sample type and research question.

For robust standardization and data normalization, consider these best practices:

- Validate Your Chosen Assay: For critical applications, especially in drug development, validate the assay for parameters like linearity, accuracy, precision, and specificity according to relevant guidelines [2].

- Account for Matrix Effects: Always use the same buffer for standard curve dilutions as the unknown samples are in. Proof of specificity should be achieved by comparing results from a placebo (buffer), a spiked placebo, and the sample solution [2].

- Understand What is Being Measured: Traditional methods like Bradford and BCA measure total protein and are influenced by the protein's composition. Techniques like ELISA and CFCA measure specific proteins, with CFCA being unique in its ability to directly quantify the active concentration of functional protein [7] [3].

- Use a Confirmatory Workflow: For critical findings, especially when analyzing complex mixtures, use a orthogonal technique for confirmation. For example, a common and robust workflow is to use ELISA for initial high-throughput quantification and Western blot for confirmatory analysis, as the latter can provide information on molecular weight and help rule out false positives [6].

The critical role of protein quantification in standardization and data normalization cannot be overstated. As the comparative data and protocols in this guide illustrate, no single method is perfect for all scenarios. The choice between colorimetric assays, immunoassays, chromatography, and emerging techniques like CFCA depends on the required specificity, the sample matrix, and the need to measure total versus active protein concentration. By carefully selecting, validating, and applying the most appropriate quantification method, researchers can ensure that their data is robust, comparable, and reliable, thereby solidifying the foundation of scientific discovery and therapeutic development.

The accurate determination of protein concentration is a fundamental prerequisite in biochemical and biopharmaceutical research, essential for everything from enzymatic studies to the formulation of therapeutic biologics [11] [12]. Among the various techniques available, ultraviolet absorbance at 280 nm (UV A280) stands as one of the most established and widely utilized methods [13]. This technique leverages the innate physicochemical properties of proteins, requiring no additional reagents, which contributes to its simplicity and speed [11] [14]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of UV A280 against other common protein quantification assays, examining the principles, advantages, and inherent limitations of each within the context of modern laboratory and bioprocessing environments. The objective is to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the data necessary to select the most appropriate quantification method for their specific application, thereby enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of their experimental outcomes.

Fundamental Principles of UV A280 Measurement

The operational principle of the UV A280 method is grounded in the Beer-Lambert law, which states that the absorbance (A) of a solution is directly proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species, the pathlength (l) of the light through the solution, and its extinction coefficient (ε); expressed as A = εlc [15]. The specificity for proteins arises from the fact that the aromatic amino acids, primarily tryptophan and tyrosine, absorb ultraviolet light strongly at a wavelength of around 280 nm [11] [13]. Phenylalanine also contributes, though to a much lesser extent due to its lower molar absorptivity [13]. The measured absorbance at this wavelength is thus directly correlated with the protein concentration, provided the extinction coefficient is known.

This method is considered "direct" because it measures a property intrinsic to the protein itself, unlike "indirect" colorimetric assays that rely on a secondary chemical reaction [16]. The entire measurement process is rapid, typically taking just a few seconds after sample loading, and is non-destructive, allowing for the recovery and subsequent use of the sample [13] [16]. The instrumentation required, a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, is a commonplace piece of equipment in life science laboratories, further cementing the method's accessibility.

Comparative Analysis of Protein Quantification Methods

No single method for protein quantification serves as a universal "gold standard," as each technique possesses distinct strengths and weaknesses influenced by the protein's unique structure and the sample's buffer composition [12]. The optimal choice depends on a balance of factors including required sensitivity, sample volume, throughput, and the presence of potential interfering substances [11] [12].

The following table summarizes the core principles and key characteristics of the most common protein quantification assays.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Protein Quantification Methods

| Method | Fundamental Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV A280 [11] [13] [16] | Absorbance by aromatic amino acids (Tyr, Trp) at 280 nm. | Quick and easy; no reagents or incubation [11]. Non-destructive; sample recovery possible [16]. Low sample volume (2-3 µL) [11] [14]. | Interference from nucleic acids, detergents [11] [13]. Relies on aromatic amino acid content [11]. Low sensitivity (< 1-50 µg/mL) [11] [14] [16]. |

| BCA Assay [11] [14] [16] | Reduction of Cu²⁺ to Cu⁺ by proteins in an alkaline medium, followed by colorimetric detection with bicinchoninic acid (λ = 562 nm). | Compatible with many detergents [11]. Wide dynamic range (20-2000 µg/mL) [11]. | Interference from reducing agents and metal ions [11]. Requires presence of specific amino acids for reduction [11]. Longer incubation (up to 30-60 min) [11] [14]. |

| Bradford Assay [11] [14] [16] | Shift in absorbance maximum (λ = 595 nm) of Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye upon binding to basic and aromatic residues. | Very fast and simple one-step assay (< 10 min) [11]. Not affected by reducing agents [11]. | Severe interference from detergents (SDS, Triton) [11]. Dye binding varies with protein composition [11]. |

| ELISA [11] | Antigen capture by specific antibody, with enzyme-linked detection producing a colorimetric signal. | High sensitivity (down to pg/mL range) [11]. High specificity for target protein [11]. High throughput capability [11]. | Time-consuming optimization and assay steps [11]. Significantly more expensive [11]. Requires specific antibodies [11]. |

Quantitative Performance Data

Experimental data from controlled studies using Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) as a standard allows for a direct comparison of the operational range and sensitivity of these methods.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics for Protein Assays (BSA Standard)

| Method | Typical Linear Range (µg/mL) | Detection Limit | Sample Volume per Assay | Total Protein Mass Required | Assay Time & Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV A280 [14] [16] | 125 - 1,000 [14] | 0.0012 mg/mL (1.2 µg/mL) [16] | 2 - 3 µL [14] | 0.38 µg [14] | ~1 minute; No reagents [11] [14] |

| BCA Assay [11] [14] | 20 - 2,000 [11] | ~20 µg/mL [11] | 30 µL [14] | 0.47 µg [14] | ~30 minutes; 1-2 steps, 37°C incubation [11] [14] |

| Bradford Assay [11] [14] | 62.5 - 1,000 [14] | ~10 µg/mL [11] | 5 µL [14] | 0.31 µg [14] | ~10 minutes; Single reagent step, room temperature [11] [14] |

| Lowry Assay [14] [16] | 5 - 200 [16] | ~5 µg/mL [16] | 100 µL [14] | 1.56 µg [14] | ~50 minutes; Multiple reagent steps [14] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for UV A280 Measurement

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for determining protein concentration using a traditional spectrophotometer [14] [16].

- Instrument Preparation: Turn on the UV-Vis spectrophotometer and allow it to warm up for approximately 15 minutes. Set the measurement wavelength to 280 nm.

- Blank Measurement: Fill a quartz cuvette with the appropriate buffer solution (the same buffer used to dissolve or dilute the protein sample). Wipe the cuvette clean and place it in the spectrophotometer. Perform a blank measurement to zero the instrument.

- Sample Measurement: Replace the blank with the protein sample. Ensure the sample is appropriately diluted so that the absorbance reading falls within the linear range of the instrument (typically A280 < 1.5) [13]. Record the absorbance value.

- Concentration Calculation: Calculate the protein concentration using the Beer-Lambert law: c = A / (ε × l), where 'A' is the measured absorbance, 'ε' is the molar extinction coefficient for the specific protein (cm⁻¹M⁻¹), and 'l' is the pathlength of the cuvette in cm. If the extinction coefficient is unknown, concentration can be estimated by comparison to a standard curve generated with a reference protein like BSA.

Protocol for BCA Assay

The BCA assay is a two-step, colorimetric method commonly performed in microplates for higher throughput [11] [14].

- Standard Curve Preparation: Prepare a series of dilutions from a standard protein stock (e.g., BSA at 2 mg/mL) to cover a concentration range from 0 to 2000 µg/mL.

- Working Reagent Preparation: Mix the BCA reagents as directed by the manufacturer to create the BCA working reagent.

- Reaction Setup: Combine 30 µL of each standard or unknown sample with 240 µL of the BCA working reagent in a microplate well. Include a blank well with buffer only.

- Incubation: Cover the plate and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Absorbance Measurement: After incubation, measure the absorbance of each well at 562 nm using a plate reader.

- Data Analysis: Plot the absorbance of the standards against their known concentrations to generate a standard curve. Use the linear equation from this curve to calculate the concentration of the unknown samples.

Advanced Applications and Technological Innovations

To overcome the inherent limitations of traditional fixed-pathlength A280 measurements, such as the need for sample dilution and a limited dynamic range, advanced technologies have been developed. Variable Pathlength Spectroscopy (VPS) is one such innovation [15].

This technology operates on the same Beer-Lambert principle but introduces a crucial variable: the pathlength (l). Instruments like the SoloVPE and FlowVPX systems use a motorized stage to automatically adjust the pathlength during measurement, taking multiple absorbance readings at different pathlengths [15]. The plot of Absorbance vs. Pathlength yields a slope, which is used to calculate concentration (c = slope / ε). This "slope spectroscopy" method offers significant advantages [15]:

- Eliminates Dilutions: The adjustable pathlength allows for the direct measurement of highly concentrated samples (up to 300 mg/mL for some antibodies).

- Enhanced Accuracy and Precision: The multi-point slope-based calculation reduces errors associated with single measurements and manual dilutions.

- Broad Dynamic Range: It reliably measures concentrations from as low as 0.1 mg/mL to over 250 mg/mL.

- Process Integration: The FlowVPX system enables in-line, real-time protein concentration monitoring during bioprocessing, serving as a powerful Process Analytical Technology (PAT) tool [15].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for performing the protein quantification methods discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Protein Quantification

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvette or UV-Transparent Microplate [14] | Holds sample for A280 measurement in a spectrophotometer or plate reader. | Must be transparent to UV light (quartz or specialized UV-plastic). Standard polystyrene plastic absorbs UV light and is not suitable. |

| Protein Standard (e.g., BSA) [14] [12] | Used to generate a calibration curve for colorimetric assays and to calibrate A280 measurements. | Choosing a standard similar in composition to the target protein improves accuracy. Concentration of the standard must be accurately determined [12]. |

| BCA Assay Kit [16] | Provides pre-mixed reagents for the Bicinchoninic Acid assay. | Kits ensure reagent consistency and often include a protein standard. Typically contain BCA solution and copper solution. |

| Bradford Assay Kit [16] | Provides a ready-to-use Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 dye solution. | Kits offer convenience and standardized dye concentration. Compatibility with detergents in the sample should be verified. |

| Buffers (e.g., PBS, Tris) | To dissolve, dilute, or dialyze the protein sample. | Buffer components must not absorb significantly at 280 nm (e.g., avoid Tris for A280 if possible) and should be compatible with the chosen assay [11]. |

UV A280 absorbance remains a cornerstone technique for protein quantification due to its simplicity, speed, and cost-effectiveness, particularly for pure samples of known extinction coefficient. However, this analysis demonstrates that its inherent limitations regarding sensitivity and susceptibility to interference make it unsuitable for all applications. The BCA and Bradford assays offer robust, sensitive alternatives for complex samples, albeit with their own specific constraints. The choice of method is not one-size-fits-all but must be guided by the sample properties, required accuracy, and experimental context. Furthermore, technological advancements like Variable Pathlength Spectroscopy are addressing the classic challenges of the A280 method, enhancing its accuracy and utility in modern biopharmaceutical development and manufacturing. A critical understanding of the principles and comparative performance of these assays is fundamental to ensuring data quality in scientific research and drug development.

Accurate protein quantification is a cornerstone of biochemical research, biopharmaceutical development, and diagnostic applications. Among the various methods available, colorimetric assays represent some of the most widely used techniques in laboratory practice worldwide. The Bradford and Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) assays, in particular, have become fundamental tools for researchers requiring rapid and sensitive determination of protein concentration in complex solutions. These methods enable critical calculations for downstream applications including protein purification, enzyme kinetics, Western blotting, and drug target validation [17] [18]. The selection between these assays can significantly impact experimental outcomes, as each operates on distinct biochemical principles with unique advantages and limitations.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the Bradford and BCA assays, focusing on their mechanisms of colorimetric detection, experimental parameters, and suitability for different sample types. Within the broader context of comparative analysis of protein quantification techniques, understanding these fundamental differences enables researchers to make informed methodological choices that enhance data reliability and reproducibility across diverse experimental systems.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Color Formation

Bradford Assay Mechanism

The Bradford assay, developed by Marion M. Bradford in 1976, relies on the unique binding properties of Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 dye to protein molecules [19] [20]. Under acidic conditions, the dye exists primarily in a protonated, cationic red form with an absorption maximum at 465 nm [21] [19]. When this dye encounters protein molecules, it undergoes a dramatic color shift through a sophisticated binding mechanism.

The binding process involves both electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions between the dye and specific amino acid residues within the protein structure. The dye's sulfonate groups form electrostatic interactions primarily with positively charged arginine residues and, to a lesser extent, with histidine, lysine, and tyrosine side chains [21] [19]. Simultaneously, hydrophobic interactions and van der Waals forces stabilize the binding through association with tryptophan, phenylalanine, and other non-polar residues [19] [22]. This dual-mode binding causes the dye to shift from its protonated red form (absorption maximum at 465 nm) to a stable, deprotonated blue anionic form (absorption maximum at 595 nm) [21] [19] [20]. The number of binding sites occupied is directly proportional to the protein concentration present in the sample, forming the quantitative basis of the assay.

BCA Assay Mechanism

The BCA assay operates through a two-step reaction mechanism that combines the classic biuret reaction with highly sensitive colorimetric detection. In the first step, proteins in an alkaline medium reduce cupric ions (Cu²⁺) to cuprous ions (Cu⁺) [21] [23] [24]. This reduction reaction occurs primarily through interactions with peptide bonds, with additional contributions from specific amino acid side chains including cysteine, tyrosine, and tryptophan residues [23] [22]. The extent of copper reduction is directly proportional to the protein concentration present in the sample.

In the second step, two molecules of bicinchoninic acid (BCA) chelate each cuprous ion (Cu⁺) to form a stable, purple-colored complex [23] [24]. This BCA-Cu⁺ complex exhibits a strong linear absorbance at 562 nm, with the intensity of the purple color directly correlating with the original protein concentration [21] [23]. Unlike the Bradford assay, which depends on dye binding to specific amino acids, the BCA assay responds primarily to the peptide backbone itself, with enhancements from specific reducing residues, resulting in generally more uniform responses across different protein types [23] [17].

Comparative Experimental Data

The distinct chemical mechanisms underlying the Bradford and BCA assays translate into significant practical differences in performance characteristics, sensitivity, and compatibility with various sample types. The table below summarizes the key comparative parameters based on experimental data from multiple studies:

Table 1: Comparative performance characteristics of Bradford and BCA assays

| Parameter | Bradford Assay | BCA Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Dye-binding shift | Copper reduction & chelation |

| Absorbance Maximum | 595 nm [21] [19] | 562 nm [21] [23] |

| Sensitivity Range | 1-20 μg/mL [21] | 25-2000 μg/mL (standard); as low as 0.5 μg/mL (micro-BCA) [21] [23] |

| Dynamic Range | Narrower [21] | Broader [21] |

| Assay Time | 5-10 minutes [21] [19] | 30 minutes - 2 hours [21] [23] |

| Protein-to-Protein Variation | Higher (response varies with basic residues) [21] [17] | Lower (more consistent across proteins) [21] [23] |

| Linearity | Limited at higher concentrations [19] | Excellent linear response [23] |

Compatibility with Chemical Reagents

The composition of protein samples often includes various buffers, detergents, and reducing agents that can interfere with colorimetric assays. The compatibility of each assay with common laboratory reagents represents a critical consideration for method selection:

Table 2: Compatibility with chemical reagents

| Reagent Type | Bradford Assay | BCA Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Detergents | Low tolerance (SDS interferes strongly) [21] [19] | High tolerance (compatible with up to 5% surfactants) [21] [23] |

| Reducing Agents | Low tolerance [21] | Variable tolerance (special kits available for compatibility) [23] |

| Buffers | Moderate tolerance [21] | High tolerance [21] |

| Chelating Agents | Generally compatible [20] | Low tolerance (EDTA interferes) [23] [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard Bradford Assay Protocol

The Bradford assay protocol involves a straightforward, single-step procedure that can be completed rapidly with minimal equipment requirements [19].

Materials Required:

- Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 dye reagent [19]

- Protein standard (typically Bovine Serum Albumin) [19]

- Unknown protein samples

- Spectrophotometer or plate reader capable of measuring at 595 nm [19]

- Cuvettes or microplates [19]

Procedure:

- Prepare Standard Curve: Create a series of protein standards with known concentrations (typically 0, 250, 500, 750, and 1500 μg/mL) diluted in the same buffer as your samples [19] [20].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute unknown protein samples appropriately (typically 1:50 dilution) in compatible buffer such as PBS [19].

- Reaction Setup: Add 100 μL of each standard and unknown sample to separate test tubes or microplate wells [20].

- Dye Addition: Add 5.0 mL of Coomassie Blue reagent to each tube (or proportionally smaller volumes for microplate formats) and mix thoroughly by vortexing or inversion [20].

- Incubation: Allow the mixture to incubate at room temperature for at least 5 minutes [19]. Note that the color development is time-sensitive, so consistent timing is critical for accurate comparisons between samples [20].

- Absorbance Measurement: Measure the absorbance at 595 nm using a spectrophotometer [19] [20].

- Data Analysis: Generate a standard curve by plotting absorbance versus protein concentration for the standards. Calculate the concentration of unknown samples using the linear regression equation from the standard curve [19].

Standard BCA Assay Protocol

The BCA assay requires a two-step reagent preparation and longer incubation but offers enhanced compatibility with diverse sample types [23] [25].

Materials Required:

- BCA Reagent A (containing BCA in alkaline buffer) [23] [25]

- BCA Reagent B (copper sulfate solution) [23] [25]

- Protein standard (typically BSA)

- Unknown protein samples

- 96-well microplate [25]

- Plate reader capable of measuring at 562 nm [23]

- Incubator (37°C or 60°C, depending on protocol)

Procedure:

- Prepare Standard Curve: Create a series of BSA standards with concentrations spanning the expected range of unknowns (e.g., 0-2000 μg/mL) [25].

- Working Reagent Preparation: Mix BCA Reagent A with BCA Reagent B at a 50:1 ratio (Reagent A:B) [25]. Prepare sufficient volume for all standards and samples.

- Sample Loading: Add 10 μL of each standard and unknown sample into microplate wells in duplicate [25].

- Reagent Addition: Add 200 μL of BCA working reagent to each well containing standard or sample [25].

- Mixing and Incubation: Cover the plate and mix by gentle tapping. Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes [23] [25]. Alternatively, for enhanced sensitivity, incubate at 60°C for 60 minutes [23].

- Absorbance Measurement: Measure the absorbance at 562 nm using a microplate reader [23] [25].

- Data Analysis: Generate a standard curve by plotting the average absorbance for each standard against its concentration. Determine unknown sample concentrations using the linear regression equation from the standard curve [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of either protein quantification assay requires specific, high-quality reagents and equipment. The following table outlines essential materials and their functions:

Table 3: Essential research reagents and equipment for protein quantification assays

| Item | Function | Both/Bradford/BCA |

|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 | Dye that binds proteins and undergoes color shift | Bradford [19] |

| BCA Reagents (A & B) | Copper solution and bicinchoninic acid for two-step detection | BCA [23] [25] |

| BSA Protein Standards | Known concentration reference for calibration curves | Both [19] [25] |

| Spectrophotometer/Plate Reader | Measures absorbance at specific wavelengths | Both [19] [25] |

| Cuvettes or Microplates | Containers for holding reaction mixtures | Both [19] [25] |

| Precision Pipettes | Accurate liquid handling for reagents and samples | Both [19] |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Compatible dilution buffer for samples | Both [19] |

| Plate Heater-Shaker | Temperature control and mixing for BCA incubation | BCA [24] |

Application Guidelines and Selection Criteria

When to Use Bradford Assay

The Bradford assay excels in specific experimental contexts where speed, sensitivity, and minimal chemical interference are prioritized. Key applications include:

- Routine Protein Determination: Ideal for quick assessments of protein concentration during purification procedures when sample purity is high and interfering substances are minimal [21].

- Limited Sample Volume: Due to its high sensitivity, the Bradford assay is beneficial when sample volume is scarce, as it requires smaller amounts of protein for accurate quantification [21].

- Educational Settings: The assay's simplicity and rapid results (under 10 minutes) make it well-suited for teaching laboratories where fundamental principles of protein quantification are demonstrated [21].

- High-Throughput Screening: The single-reagent, rapid development time enables efficient processing of large sample numbers in 96-well plate formats [19].

When to Use BCA Assay

The BCA assay offers distinct advantages for more complex samples and applications requiring high accuracy across diverse protein types:

- Samples Containing Detergents: The BCA assay demonstrates superior tolerance for various detergents and surfactants commonly used in cell lysis and protein solubilization, making it ideal for cell culture lysates and membrane protein preparations [21] [23].

- Comparative Studies: The BCA assay's more uniform response across different protein types makes it preferable for experiments comparing concentrations of different proteins or protein mixtures [21] [23].

- Low Concentration Samples: Enhanced and micro-BCA protocols can detect protein concentrations as low as 0.5-20 μg/mL, making them suitable for dilute protein solutions [23].

- Automated High-Throughput Applications: Despite longer incubation times, the BCA assay's compatibility with diverse sample types and consistency across proteins makes it appropriate for automated screening platforms [21] [24].

The Bradford and BCA colorimetric assays represent two fundamentally different approaches to protein quantification, each with distinct mechanisms and optimal applications. The Bradford assay operates through direct dye-binding to basic and aromatic amino acid residues, resulting in a rapid color shift measurable at 595 nm. In contrast, the BCA assay functions through copper reduction by peptide bonds followed by bicinchoninic acid chelation, producing a purple complex detectable at 562 nm.

Selection between these methods should be guided by experimental requirements, including the need for speed versus accuracy, sample composition, and the nature of the proteins being quantified. The Bradford assay offers unparalleled speed and simplicity for pure protein samples, while the BCA assay provides superior compatibility with detergents and more consistent performance across different protein types. Understanding these core mechanisms and performance characteristics enables researchers to implement the most appropriate quantification method for their specific experimental context, thereby ensuring reliable and reproducible results in protein-based research and biopharmaceutical applications.

Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) coupled with Evaporative Light Scattering Detection (ELSD) represents a powerful analytical platform for separating and detecting analytes that lack chromophores necessary for conventional UV detection. RP-HPLC separates compounds based on their hydrophobicity using a non-polar stationary phase and a polar mobile phase, making it one of the most versatile chromatographic techniques for analytical scientists. ELSD serves as a quasi-universal detection system that measures the light scattered by non-volatile analyte particles after nebulization and evaporation of the mobile phase, enabling detection of compounds regardless of their optical characteristics [26] [27].

This combination is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical research, food analysis, and biofuel production monitoring where analysts frequently encounter molecules with insufficient UV absorption. The HPLC-ELSD system provides distinct advantages over other detection methods like Refractive Index (RI) detection by offering compatibility with gradient elution, and compared to Mass Spectrometry (MS), it presents a more cost-effective solution with simpler operation and maintenance [27] [28]. Within the context of protein quantification research, while these techniques are not typically used for direct protein concentration measurement, they provide critical analytical capabilities for characterizing lipid components in drug delivery systems, monitoring biodiesel production intermediates, and quantifying excipients in biopharmaceutical formulations [26] [27].

Technical Comparison of Detection Strategies

Performance Characteristics of Common Detectors

The selection of an appropriate detection strategy for HPLC applications depends on multiple factors including the chemical properties of target analytes, required sensitivity, mobile phase compatibility, and economic considerations. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major detection approaches used with HPLC systems:

Table 1: Comparison of HPLC Detection Methods

| Detection Method | Detection Principle | Gradient Compatibility | Sensitivity | Universal Response | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Detection | Absorption of light by chromophores | Excellent | High (ng-pg) | No (requires chromophores) | Limited to compounds with UV chromophores |

| ELSD | Light scattering by non-volatile particles | Excellent | Moderate (µg-ng) | Yes (for non-volatiles) | Non-linear response; analyte must be less volatile than mobile phase |

| CAD | Charged aerosol detection | Excellent | High (ng-pg) | Yes (for non-volatiles) | More expensive than ELSD; requires nitrogen source |

| RI Detection | Refractive index change | Poor | Low (µg) | Yes | Sensitive to temperature/pressure changes; no gradient elution |

| MS Detection | Mass-to-charge ratio | Excellent | Very high (pg-fg) | Yes | High cost; complex operation; matrix effects |

Among these options, ELSD has emerged as a robust compromise between performance, universality, and operational practicality. Unlike UV detection, ELSD does not require chromophores in the analyte structure, making it suitable for lipids, carbohydrates, polymers, and other compounds with poor UV absorbance [27] [28]. Compared to RI detection, ELSD offers superior sensitivity and full compatibility with gradient elution, enabling more complex separations [26]. While Charged Aerosol Detection (CAD) typically provides better sensitivity, ELSD benefits from lower purchase costs, simpler operation, and better robustness for routine quality control activities [27] [28].

Quantitative Performance Considerations

A critical aspect of ELSD performance is its non-linear response characteristics. The relationship between analyte mass and detector response typically follows a power law function represented by the equation: ( A = a \times M^b ), where ( A ) is the peak area, ( M ) is the analyte mass, ( a ) is the response factor, and ( b ) is the regression coefficient [29] [30]. This non-linearity distinguishes ELSD from "linear" detectors like UV, CLND, and MS where ( b = 1.00 ). For ELSD in ideal Mie scattering conditions, ( b = 1.33 ), which leads to systematic underestimation of chromatographically resolved impurities and consequent overestimation of analyte purity when using uncalibrated area percentage calculations [30].

This quantitative limitation has important practical implications. Research has demonstrated that an impurity present at 10% mass/mass may appear as only 5% by ELSD area percentage, and impurities at 1% mass/mass might contribute only 0.2% of total area [30]. This suppression effect becomes more pronounced as the true amount of impurity decreases. The response factors also vary significantly between compounds, with studies showing log ( a ) values ranging from 2.02 to 2.18 even for closely related compounds within a library, representing a 45% difference in response factor [30]. These quantitative characteristics must be carefully considered when implementing HPLC-ELSD for analytical applications requiring high accuracy.

Experimental Applications and Protocols

Analysis of Biodiesel Production Intermediates

The transesterification reaction used for biodiesel production generates a complex mixture of triacylglycerols (TAG), diacylglycerols (DAG), monoacylglycerols (MAG), free fatty acids (FFA), and fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) that must be monitored to ensure final product quality meets international standards (e.g., EN 14214 in Europe and ASTM D6751 in the USA) [26].

Table 2: RP-HPLC-ELSD Method for Biodiesel Analysis

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Column Type | Reversed-Phase UHPLC |

| Mobile Phase | Gradient of water/acetonitrile/trifluoroacetic acid |

| ELSD Conditions | Nebulizer temperature: 40°C; evaporator temperature: 60°C |

| Separation Time | 17 minutes |

| Compounds Quantified | 21 compounds including FFA, MAG, DAG, TAG, FAME |

| Linear Range | 10-500 μg/mL for most analytes |

| Application | Monitoring transesterification reaction progress |

The developed RP-UHPLC-ELSD method successfully separated and quantified at least 21 compounds in a single 17-minute run, providing a significant advantage over conventional GC methods that require derivatization of acylglycerols and suffer from high-temperature column issues [26]. The method was validated and shown to be suitable for simultaneous analysis of FFA, MAG, and DAG, offering a rapid solution for both research and industrial quality control contexts.

Quantification of Lipids in Nanoparticle Formulations

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have gained significant importance as drug delivery systems, particularly for mRNA vaccines. Quality control of LNP formulations requires precise quantification of lipid components, including ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, and PEGylated lipids [27].

Experimental Protocol: HPLC-DAD/ELSD for Lipid Analysis

- Column: Poroshell C18 column (50°C)

- Mobile Phase: Step gradient of water/methanol mixtures with 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid

- Detection: Simultaneous DAD/ELSD detection

- Validated Parameters: Linearity (R² ≥ 0.997), precision (RSD < 5%), accuracy (recoveries: 92.9-108.5%)

- Application: Analysis of novel synthetic lipids (CSL3, PolyEtOx) and conventional lipids (DSPC, DOPE, cholesterol, DSPE-PEG2000)

The method was successfully validated according to ICH Q2(R1) & (R2) guidelines and applied to the analysis of several liposome formulations at key development stages [27]. It enabled the detection of lipid degradation products under various stress conditions (basic, acidic, oxidative), demonstrating its utility for stability testing of LNP formulations.

Analysis of Inorganic Ions in Pharmaceutical Formulations

The determination of inorganic ions such as sodium and phosphate is critical in pharmaceutical development to ensure product consistency and safety. A recent innovative application of HPLC-ELSD demonstrated simultaneous quantification of these ions in aripiprazole extended-release injectable suspensions [31].

Experimental Protocol: Inorganic Ion Analysis

- Column: Amaze TH trimodal column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm)

- Mobile Phase: 20 mM ammonium formate (pH 3.2)/acetonitrile (70:30 v/v)

- Flow Rate: 1 mL/min

- ELSD Conditions: Drift tube temperature: 70°C; nebulizing gas pressure: 3.2 bar (N₂)

- Injection Volume: 20 μL

- Validation: Linearity (R² > 0.99), precision (RSD < 10%), accuracy (95-105% recovery)

This method utilized a trimodal stationary phase combining reversed-phase, cation-exchange, and anion-exchange mechanisms to retain and separate the highly polar inorganic ions [31]. The approach provided a simpler and more cost-effective alternative to ion chromatography or ICP-MS for routine quality control of complex pharmaceutical matrices.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Figure 1: HPLC-ELSD Analytical Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of RP-HPLC-ELSD methods requires specific reagents and materials optimized for the particular application. The following table details essential components for the experimental protocols discussed:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HPLC-ELSD Applications

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stationary Phase | C18, C8, or trimodal columns | Compound separation based on hydrophobicity | Poroshell C18 for lipids [27]; Amaze TH for ions [31] |

| Organic Solvents | HPLC-grade acetonitrile, methanol | Mobile phase components | Acetonitrile/water gradients [26] [27] |

| Acid Modifiers | Trifluoroacetic acid, formic acid | Improve peak shape and separation | 0.1% TFA in mobile phase [27] |

| Volatile Salts | Ammonium formate, ammonium acetate | Mobile phase additives for ion separation | 20 mM ammonium formate [31] |

| Reference Standards | Analyte-specific certified standards | Method calibration and quantification | Lipid standards for LNP analysis [27] |

Advantages and Limitations in Protein Research Context

While RP-HPLC-ELSD is not typically employed for direct protein quantification, its utility in related biopharmaceutical characterization is significant. In the context of comparative protein quantification techniques research, understanding the position of HPLC-ELSD within the analytical landscape is valuable.

The primary advantages of HPLC-ELSD include its universal response for non-volatile compounds, compatibility with gradient elution, and relatively low operational costs compared to MS-based detection [27]. These characteristics make it particularly suitable for monitoring chemical reactions involving non-chromophoric compounds, quantifying excipients in formulated products, and analyzing compounds with poor UV absorbance such as lipids and carbohydrates [26] [28].

However, the technique has notable limitations for quantitative work. The non-linear response requires careful calibration with authentic standards, and the sensitivity is generally lower than UV detection for compounds with strong chromophores or CAD for universal detection [30] [28]. Additionally, the response factor variability between different compounds necessitates individual calibration for each analyte when accurate quantification is required [30].

When compared with mainstream protein quantification methods like Bradford, BCA, Lowry, or UV absorbance at 280 nm, HPLC-ELSD serves complementary rather than competing roles. While the conventional protein assays quantify total protein content based on specific chemical reactions or structural features, HPLC-ELSD excels at characterizing specific non-protein components in biopharmaceutical formulations, such as lipids in nanoparticle drug delivery systems or intermediates in enzymatic reactions [27] [12] [17].

RP-HPLC with ELSD detection provides a versatile analytical platform for separating and detecting analytes that challenge conventional UV-based detection systems. The technique offers particular value in monitoring chemical reactions involving lipids, carbohydrates, and other non-chromophoric compounds, as demonstrated in biodiesel production, lipid nanoparticle characterization, and pharmaceutical excipient analysis.

While the non-linear response characteristics of ELSD present quantitative challenges that require careful method validation, the benefits of universal detection, gradient compatibility, and operational simplicity make it an important tool in the analytical chemist's arsenal. In the broader context of protein quantification research, HPLC-ELSD serves complementary functions rather than direct competition with established protein assays, highlighting the need for multiple orthogonal analytical techniques to fully characterize complex biological and pharmaceutical systems.

As analytical demands continue to evolve in pharmaceutical and biotechnology research, the combination of robust separation mechanisms with universal detection principles will remain essential for addressing challenging analytical problems involving diverse chemical entities with varying physicochemical properties.

In the field of protein quantification, few techniques have demonstrated the enduring utility and widespread adoption of the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). As biological research and drug development increasingly require precise measurement of specific proteins within complex mixtures, ELISA has maintained its status as a gold standard methodology due to its exceptional sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. The technique's fundamental principle relies on the specific binding between an antigen and an antibody, coupled with an enzymatic reaction that generates a measurable signal [32]. This elegant combination provides researchers with a powerful tool for quantifying target proteins with precision unmatched by many alternative methods.

The versatility of ELISA is evidenced by its application across diverse scientific domains. In clinical diagnostics, it enables the detection of disease biomarkers; in drug discovery, it facilitates the assessment of therapeutic antibody efficacy and pharmacokinetic properties; and in basic research, it allows for the accurate quantification of protein expression levels [33]. A critical advantage of ELISA lies in its ability to detect specific target proteins within heterogeneous samples containing numerous non-target proteins, a challenge that frequently confounds conventional protein quantification methods [1]. This capability is particularly valuable when working with large transmembrane proteins or low-abundance targets that require exceptional detection sensitivity.

Comparative Analysis of Protein Quantification Techniques

Performance Comparison of Major Protein Quantification Methods

To objectively evaluate ELISA's position within the protein quantification landscape, we compared its key performance metrics against other commonly used techniques, including Western Blot, Mass Spectrometry, and the newer Olink Proximity Extension Assay (PEA).

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Quantification Techniques

| Feature | ELISA | Western Blot | Mass Spectrometry | Olink PEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (pg/mL) [34] | Moderate (ng/mL) [34] | Low [35] | High [35] |

| Throughput | High [6] [34] | Low [34] [35] | Low [35] | Medium [35] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Low (single protein) [35] | Low to Moderate [6] | High [35] | High (up to 384 proteins) [35] |

| Sample Input | ~100 µL [35] | Varies | ~150 µL [35] | ~1 µL [35] |

| Quantification Capability | Absolute and relative [35] | Semi-quantitative [34] | Absolute and relative [35] | Absolute and relative [35] |

| Molecular Weight Information | No [34] | Yes [6] [34] | Yes [35] | No |

| Detection of Post-Translational Modifications | No [34] | Yes [34] | Yes [35] | Limited |

| Time Required | 4-6 hours [34] | 1-2 days [34] | Time-intensive [35] | Varies |

Experimental Evidence: ELISA vs. Conventional Protein Assays

Recent research has provided direct experimental comparisons between ELISA and conventional protein quantification methods. A 2024 study systematically evaluated the efficacy of common protein quantification methods (Lowry, bicinchoninic acid [BCA], and Coomassie Bradford assays) against a newly developed ELISA for quantifying Na,K-ATPase (NKA), a large transmembrane protein [1].

The results demonstrated that the three conventional methods significantly overestimated the concentration of NKA compared with ELISA. This overestimation was attributed to the samples containing a heterogeneous mix of proteins, including a significant amount of non-target proteins, which are detected by the conventional methods but not by the target-specific ELISA [1]. Furthermore, when applying the protein concentrations determined by the different methods to in vitro assays, the variation in the resulting data was consistently low when the assay reactions were prepared based on concentrations determined from ELISA, highlighting its superior reliability for downstream applications [1].

This study underscores a critical limitation of conventional methods: their mechanism of action makes them less ideal for specific quantification of target proteins within complex mixtures, particularly for transmembrane proteins integrated in the plasma membrane [1].

ELISA Methodology: Principles and Protocols

Core Principles and Workflows

ELISA operates on the principle of antigen-antibody binding, where the detection antibody is conjugated to an enzyme that produces a measurable signal when exposed to its substrate [32]. The intensity of this signal is directly proportional to the concentration of the target molecule, allowing for accurate quantification [34]. The four main types of ELISA are:

- Direct ELISA: Uses a single enzyme-conjugated primary antibody that binds directly to the target antigen [32] [36].

- Indirect ELISA: Employs an unlabeled primary antibody followed by an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody that recognizes the primary antibody [32] [36].

- Sandwich ELISA: The target antigen is bound between a capture antibody attached to the plate and a detection antibody in solution, providing high specificity [32] [36].

- Competitive ELISA: Used for detecting small antigens, where the sample antigen competes with a reference antigen for binding to antibodies [32] [36].

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in a standard direct ELISA protocol:

Figure 1: Direct ELISA workflow diagram showing the sequential steps from coating to quantification.

For enhanced sensitivity and specificity, the sandwich ELISA format is often preferred. The following diagram details this approach:

Figure 2: Sandwich ELISA workflow diagram demonstrating the enhanced specificity achieved through dual antibody binding.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Indirect ELISA

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for performing an indirect ELISA, adapted from established clinical laboratory practices [36]:

Specimen Requirements and Reagents:

- Polystyrene 96-well plates

- Primary detection antibody specific to the target protein

- Secondary enzyme-conjugated antibody complementary to the primary antibody

- Antigen of interest for coating

- Blocking buffer (typically bovine serum albumin - BSA)

- Wash buffer (phosphate-buffered saline - PBS with non-ionic detergent)

- Enzyme substrate (e.g., p-nitrophenyl-phosphate for alkaline phosphatase)

Procedure:

- Coating: Add antigens diluted in coating buffer to plates. Incubate for one hour at 37°C or overnight at 4°C.

- Washing: Wash plates with buffer to remove unbound antigens.

- Blocking: Add blocking buffer (BSA) to cover all well surfaces. Incubate at room temperature for 1-2 hours to prevent nonspecific binding.

- Washing: Wash plates to remove excess blocking buffer.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Add primary detection antibody that binds to the protein of interest. Incubate for one hour at 37°C.

- Washing: Wash plates thoroughly to remove unbound primary antibody.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Add enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody complementary to the primary antibody. Incubate for one hour at 37°C.

- Washing: Wash plates thoroughly to remove unbound secondary antibody.

- Substrate Addition: Add enzyme-specific substrate to each well. Incubate for 15-30 minutes at room temperature to allow color development.

- Signal Detection: Measure color change using a spectrophotometer or plate reader.

- Quantification: Plot a standard curve using serial dilutions of known concentrations and calculate sample concentrations based on the standard curve [36].

Critical Considerations:

- Each wash step should be performed 2 or more times to ensure complete removal of unbound materials [36].

- The optimal concentrations for coating antigens and antibodies should be determined empirically for each new application.

- Incubation times may be adjusted based on the affinity of the antibodies and the abundance of the target protein.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for ELISA

Successful implementation of ELISA requires specific high-quality reagents and instruments. The following table details the essential components needed for establishing a robust ELISA protocol:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for ELISA

| Item | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Microplates | Solid surface for immobilization | 96-well polystyrene plates [36] |

| Coating Antibody/Antigen | Capture molecule bound to plate surface | Target-specific antibody or purified antigen [32] |

| Blocking Buffer | Prevents nonspecific binding | Bovine serum albumin (BSA), non-fat milk, or other proteins [34] [36] |

| Detection Antibodies | Binds to target with high specificity | Primary and secondary antibodies; enzyme-conjugated [32] |

| Wash Buffer | Removes unbound components | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with detergent [36] |

| Enzyme Substrate | Generates detectable signal | Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or alkaline phosphatase (AP) substrates [36] |

| Plate Reader | Measures signal intensity | Spectrophotometer for colorimetric detection [33] |

The selection of high-affinity antibodies is particularly crucial, as "the backbone of any ELISA assay, which makes it a great assay, is the use of particular, high-affinity antibodies to your target of interest" [33]. The quality of antibodies directly impacts the specificity and sensitivity of the assay.

Advantages and Limitations in Target-Specific Quantification

Key Advantages of ELISA

ELISA offers several compelling advantages that explain its enduring popularity as a quantification method:

High Sensitivity and Specificity: ELISA can detect proteins at concentrations as low as picograms per milliliter (pg/mL), making it suitable for quantifying low-abundance proteins [34]. The use of specific antibodies enables precise target detection even in complex biological mixtures [33].

Quantitative Capabilities: Unlike semi-quantitative methods like Western Blot, ELISA provides absolute quantification of protein concentrations when used with appropriate standard curves [6] [35].

High-Throughput Capacity: The 96-well plate format enables simultaneous processing of multiple samples, making ELISA ideal for screening large sample sets [6] [34]. This format is also amenable to automation, further increasing throughput [33].

Robustness and Reproducibility: Well-optimized ELISA protocols demonstrate excellent inter-assay and intra-assay reproducibility, providing reliable data for comparative studies [32].

Broad Application Range: ELISA has been successfully applied to diverse sample types, including serum, plasma, cell lysates, and tissue homogenates [32] [36].

Limitations and Considerations

Despite its many strengths, researchers should be aware of several limitations:

Limited Structural Information: Unlike Western Blot or mass spectrometry, ELISA does not provide information about protein size, isoforms, or post-translational modifications [6] [34].

Potential for Interference: ELISA can yield false positives or negatives due to assay conditions, sample characteristics, or cross-reactivity between antibodies [32].

Antibody Dependency: The quality of ELISA results is entirely dependent on the specificity and affinity of the antibodies used [33]. Poor antibody selection can compromise the entire assay.

Limited Dynamic Range: The quantification range of ELISA can be limited, potentially leading to saturation or detection limitations at extreme concentrations [32].

Future Directions: Next-Generation ELISA Technologies

The field of ELISA continues to evolve with advancements aimed at addressing current limitations. "Next-generation ELISA" technologies incorporate innovations such as:

- Digital ELISA: Enables ultra-sensitive, single-molecule detection for quantifying extremely low-abundance proteins [37].

- Multiplex ELISA: Allows simultaneous quantification of multiple analytes from a single sample, dramatically increasing information content while conserving sample [32] [37].

- Advanced Detection Methods: Transition from traditional colorimetric detection to chemiluminescent, fluorescent, and electrochemiluminescent reporters that offer improved sensitivity and dynamic range [33] [37].

- Microfluidic and Lab-on-a-Chip Platforms: Miniaturization of ELISA protocols reduces reagent consumption and analysis time while increasing portability [32] [37].

- Automation and Integration: Fully automated ELISA systems streamline workflows, reduce human error, and enable high-throughput processing [33].

The global market for these advanced ELISA technologies is predicted to grow significantly, with projections estimating a rise from US$519.4 million in 2022 to US$754.38 million by 2030, reflecting the continued importance and evolution of this methodology [37].

ELISA remains an indispensable tool in the protein quantification arsenal, offering an optimal balance of sensitivity, specificity, and practicality for target-specific protein detection. While newer technologies have emerged that address certain limitations of traditional ELISA, its position as a gold standard for protein quantification is secured by its robust performance, quantitative reliability, and adaptability to diverse research needs. For researchers requiring accurate, target-specific quantification of proteins in complex mixtures, ELISA continues to provide a methodology against which newer technologies are often measured. As the technique evolves through incorporation of novel detection strategies and automation, its utility in both basic research and applied clinical settings is likely to expand further, maintaining its relevance in the rapidly advancing field of protein science.

In modern proteomics, the accurate quantification of proteins across biological samples is fundamental for advancing research in drug discovery, biomarker identification, and systems biology. Mass spectrometry (MS) has emerged as the principal technology for large-scale protein analysis, with quantification strategies primarily bifurcating into label-free and label-based methodologies. The choice between these approaches significantly influences experimental outcomes, affecting proteome coverage, quantification accuracy, and analytical throughput [38]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these foundational strategies, drawing on recent benchmarking studies to delineate their performance characteristics, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols. Framed within a broader thesis on comparative protein quantification technique research, this overview is designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the evidence necessary to select the optimal method for their specific experimental context.

Label-free quantification (LFQ) determines relative protein abundance by analyzing data from individual LC-MS runs without the use of isotopic labels. Quantification is typically based on either the precursor signal intensity at the MS1 level, by integrating the chromatographic peak area of peptide ions, or spectral counting, which tallies the number of fragmentation spectra identified for a given peptide [39]. Its major advantages include simpler sample preparation, lower cost due to the absence of labeling reagents, and a wider dynamic range, which collectively facilitate the identification of a broader range of proteins, especially in complex samples [38].

In contrast, label-based quantification employs stable isotopes to tag proteins or peptides from different samples, allowing them to be pooled and analyzed simultaneously in a single LC-MS run. Common methods include Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) and Isobaric Tag for Relative and Absolute Quantitation (iTRAQ), which are forms of isobaric labeling. During MS/MS analysis, these tags release reporter ions whose intensities provide quantitative data for each sample [40]. The primary strengths of label-based approaches include higher multiplexing capacity, enabling the parallel analysis of up to 16 samples [41] [38], and reduced technical variability as all samples experience identical LC-MS conditions post-pooling [38].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Label-Free and Label-Based Quantification Strategies

| Feature | Label-Free Proteomics | Label-Based Proteomics (e.g., TMT, iTRAQ) |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Simpler, less time-consuming [38] | More complex, requires a labeling step and reaction optimization [38] |

| Cost | Lower; no labeling reagents needed [38] | Higher, due to cost of labeling reagents [38] |

| Proteome Coverage | Higher; can identify up to 3x more proteins in complex samples [38] | Lower, partly due to increased sample complexity from multiplexing [38] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited; separate runs for each sample [38] | High; up to 16 samples in a single run [38] |

| Quantification Accuracy & Precision | Moderate; can be influenced by run-to-run variation [38] | Generally higher for low-abundance proteins; reduced technical variability [38] |

| Dynamic Range | Wider [38] | Narrower [38] |

| Instrument Time | More, as each sample is run individually [38] | Less for multiplexed samples, as multiple samples are run together [38] |

| Data Analysis Complexity | High, requires sophisticated chromatographic alignment and normalization [39] [38] | High, requires careful normalization and correction for factors like ratio compression [40] |

Performance Benchmarking: Experimental Data

Independent benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated these methodologies, providing critical data to inform selection.

A Benchmarking Study on Host Cell Protein (HCP) Monitoring

A rigorous 2024 study evaluated six MS/MS search algorithms for label-free HCP monitoring using complex samples spiked with isotopically labeled standards. The study, which employed a Bayesian modeling framework, revealed significant performance variability:

- Byos and SpectroMine excelled in quantitative accuracy with minimal bias.

- FragPipe provided high precision and quantifiability.

- PEAKS offered the deepest protein coverage.

- Mascot showed strong trueness in its measurements.

- MaxQuant exhibited moderate identification performance with greater variability at lower spike levels [42].

This study underscores that even within the label-free domain, the choice of data processing software is a critical determinant of performance outcomes in applications requiring high reliability, such as biopharmaceutical development [42].

Comparative Analysis for Subcellular Proteomics

A comprehensive study compared four quantitative MS approaches—label-free (MS1 and DIA) and isobaric labeling (TMT-MS2 and TMT-MS3)—for mapping subcellular proteomes. The objective was not merely accurate protein measurement, but correct assignment of protein localization.

- TMT-MS2 provided the greatest proteome coverage and the lowest proportion of missing values when analyzing orthogonal fractionation methods. However, it suffered from ratio compression, narrowing its accurate dynamic range [40].

- Despite its quantitative inaccuracy, TMT-MS2 assigned protein localization with similar quality to other methods, because the errors applied systematically to both marker proteins and unknowns [40].

- TMT-MS3, MS1, and DIA showed similar and superior dynamic range in accurate quantification compared to TMT-MS2 [40].

This research highlights that the "best" method depends on the ultimate experimental goal. For subcellular localization aiming for maximal proteome coverage with minimal missing data, TMT-MS2 was highly effective, whereas for precise fold-change measurements, other methods proved more accurate [40].

Benchmarking for Limited Proteolysis-MS (LiP-MS)

A 2025 benchmark evaluating workflows for LiP-MS, a technique for detecting protein structural changes, directly compared TMT isobaric labeling and Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA), a label-free method.

- TMT Labeling enabled the quantification of more peptides and proteins with lower coefficients of variation [41].

- DIA-MS exhibited greater accuracy in identifying true drug targets and showed stronger dose-response correlations for peptides derived from protein targets [41].

This indicates a trade-off between the depth and precision of measurement (favoring TMT) and quantitative accuracy in a complex biological assay (favoring DIA) [41].

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Findings from Benchmarking Studies

| Study Context | Key Finding for Label-Free | Key Finding for Label-Based (TMT) |

|---|---|---|

| HCP Monitoring [42] | Software choice drastically affects performance (e.g., PEAKS for coverage; Byos/SpectroMine for accuracy). | Not the focus of this particular study. |

| Subcellular Proteomics [40] | MS1 and DIA showed superior dynamic range and accuracy of measurement. | TMT-MS2 offered greatest coverage and lowest missing data, despite ratio compression. |

| Limited Proteolysis-MS (LiP-MS) [41] | DIA provided greater accuracy in target identification and stronger dose-response correlation. | TMT enabled quantification of more peptides/proteins with lower technical variation. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of the underlying data, here are the summarized protocols from key benchmarking studies.

This protocol was used to compare TMT-MS2, TMT-MS3, MS1, and DIA on rat liver fractions.

1. Sample Preparation:

- Source: Rat liver differential centrifugation and Nycodenz density gradient fractions.

- Protein Processing: Proteins (20 μg per sample) were reduced, alkylated, and digested using the FASP method with Lys-C and trypsin.

- Standard Addition: A bacterial protein standard (DrR57) was spiked into samples in a dilution series for quality control.

2. Data Acquisition:

- TMT Workflow: Peptides from different fractions were labeled with TMT10plex reagents, pooled, and fractionated. Data was acquired on an Orbitrap instrument.

- TMT-MS2: Precursor ions were isolated and fragmented (MS2), with reporter ions quantified in the MS2 spectrum.

- TMT-MS3: MS2 fragment ions were isolated and further fragmented (MS3), with reporter ions quantified in the MS3 spectrum to minimize ratio compression.

- Label-Free Workflow (MS1 & DIA): Individual fractions were analyzed separately.

- MS1 (Peak Intensity): Quantification based on extracted ion chromatograms of precursor peptides.

- DIA (Data-Independent Acquisition): The instrument cyclically fragmented all precursors within sequential, wide m/z windows.

3. Data Analysis:

- Protein identification and quantification were performed using software specific to each method (e.g., MaxQuant for LFQ).

- Protein localization was assessed using a clustering algorithm to assign known marker proteins to their correct subcellular compartments.

This protocol benchmarked DIA and TMT for detecting drug-induced protein structural changes.

1. Biological Sample Treatment:

- Cell Culture: K562 human myeloid leukemia cells were cultured and harvested.

- Limited Proteolysis: Cell lysates were treated with staurosporine (across an 8-point dose-response) or vehicle control. Proteinase K was added at a 1:100 (enzyme:substrate) ratio for 5 minutes at 25°C to conduct limited proteolysis.

- Digestion Quenching & Completion: Reactions were stopped by heat denaturation. Sodium deoxycholate (DOC) was added, and proteins were reduced, alkylated, and digested to completion first with Lys-C and then with trypsin.

2. Sample Preparation for MS:

- For DIA: 20 μg of desalted peptides were used.

- For TMT: 100 μg of peptides were labeled with TMTpro 16plex reagents. Labeled samples were pooled and desalted.

3. Data Acquisition & Analysis:

- DIA-MS: Data was acquired on an Orbitrap Astral or similar instrument using DIA methods. Data was processed using software such as DIA-NN or Spectronaut.

- TMT-MS: Data was acquired using an LC-MS method optimized for TMT reporter ion detection. Data was processed with tools like FragPipe.

- Hit Confirmation: Performance was evaluated based on the accurate identification of known staurosporine targets and the strength of the peptide dose-response.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core procedural steps and logical relationships for the two main quantification strategies, highlighting their parallel paths and key differences.