Protein Misfolding and Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Mechanisms, Models, and Therapeutic Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role of protein misfolding and aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and ALS.

Protein Misfolding and Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Mechanisms, Models, and Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role of protein misfolding and aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and ALS. It explores the fundamental mechanisms of proteostasis collapse, oligomer toxicity, and prion-like propagation. For researchers and drug development professionals, the content details advanced methodological approaches including AI-driven prediction platforms and mathematical modeling. It further examines current challenges in therapeutic development, troubleshooting strategies for high-concentration formulations, and comparative analysis of therapeutic modalities targeting protein aggregation pathways. The synthesis of foundational science with cutting-edge applications offers a valuable resource for accelerating therapeutic innovation in this field.

The Proteostasis Crisis: Unraveling Core Mechanisms of Protein Misfolding in Neurodegeneration

Protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, is a fundamental biological process that maintains the cellular proteome in a functional state through an integrated system of synthesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation [1]. This exquisite balance ensures that proteins acquire and retain their correct three-dimensional structures, essential for executing myriad biological functions from catalytic activity to signal transduction [1] [2]. The proteostasis network (PN) represents approximately 3,000 genes that encode components working cooperatively across all three processes to provide surveillance of proteome integrity and limit toxic protein accumulation [3]. Disruption of this delicate balance—a state termed dysproteostasis—leads to protein misfolding, aggregation, and cellular dysfunction, underpinning a growing list of human diseases with particular significance in neurodegenerative disorders [4] [1].

The Proteostasis Network: Core Components and Functional Relationships

The PN encompasses three interconnected functional domains: protein synthesis, folding and trafficking, and degradation [3]. These components function collaboratively across nine organelle or process-specific branches: PN regulation and protein translation, nuclear, mitochondrial, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), extracellular and cytonuclear proteostasis, ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), and autophagy-lysosome pathway (ALP) [3].

Table 1: Core Components of the Proteostasis Network

| Functional Domain | Key Elements | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Synthesis & Folding | Ribosomes, Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs: HSP70, HSP90, HSP60, small HSPs), Chaperonins (TRiC/CCT) | Nascent polypeptide folding; preventing aggregation; refolding misfolded proteins; protein trafficking [3] [1] [2] |

| Protein Degradation | Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS), Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway (ALP), Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy (CMA) | Recognition and degradation of misfolded, damaged, or excess proteins [4] [3] [2] |

| Cellular Compartments & Stress Responses | Endoplasmic Reticulum (UPR), Mitochondrial UPR, Heat Shock Response (HSR) | Compartment-specific folding quality control; adaptive stress response activation [3] [1] [5] |

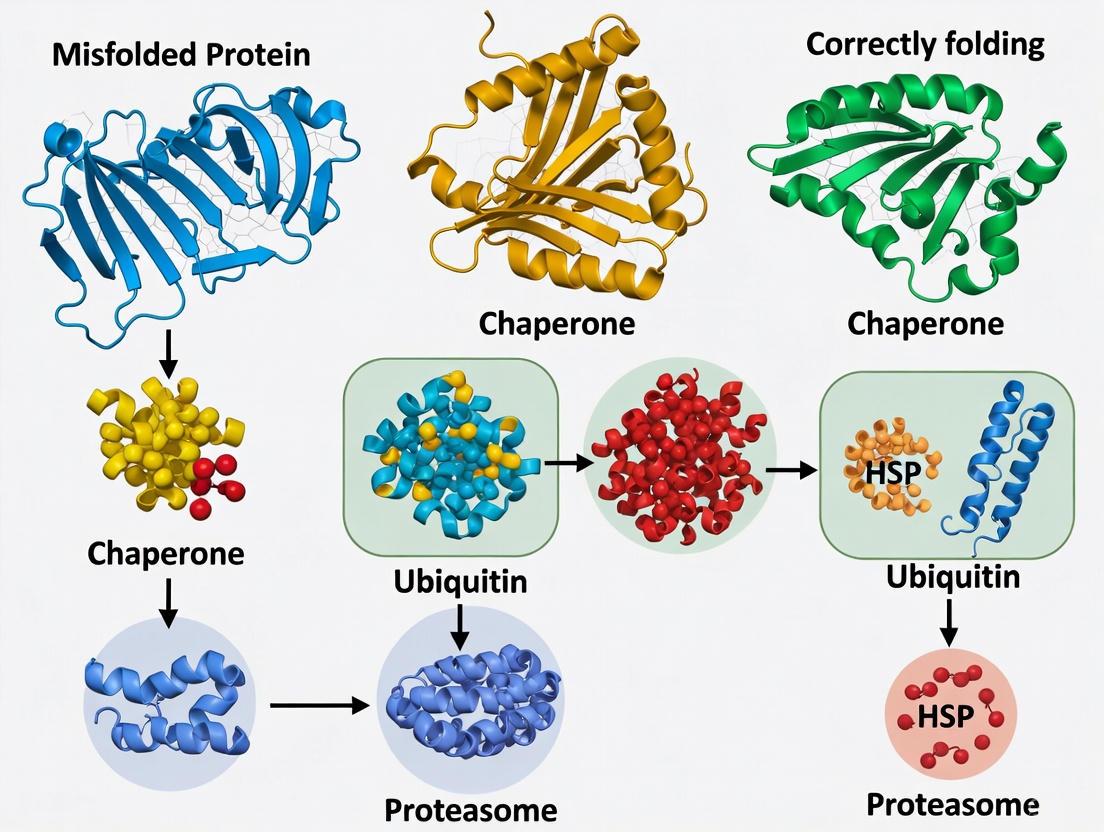

Diagram: The Integrated Proteostasis Network

Diagram Title: Integrated Proteostasis Network Components

Proteostasis Dysregulation in Neurodegenerative Diseases

In neurodegenerative diseases, collectively known as proteinopathies, proteostasis failure manifests through the accumulation of toxic, misfolded protein aggregates that lead to synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss [4] [3]. The three most common dementias—Alzheimer's Disease (AD), Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB), and Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD)—are all characterized by distinct protein aggregates: AD by extracellular amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and intracellular hyperphosphorylated tau tangles; DLB by α-synuclein aggregates; and FTD by tau or TDP-43 proteins [4]. Aging represents the most significant risk factor for proteostasis decline, as chaperone expression and degradation efficiency progressively wane, rendering post-mitotic neurons particularly vulnerable to accumulated damage over a lifetime [4] [3].

Quantitative proteomic analyses of post-mortem human brains, animal models, and iPSC-derived neurons have confirmed that PN dysfunction is an early event in pathogenesis [4]. Mass spectrometry studies reveal that PN components heavily implicated in dementia pathogenesis include chaperones and the endolysosomal network (ELN), with ELN defects observed reproducibly and early in AD brains [4]. Genome-wide association studies further show enrichment of ELN proteins among AD risk factors [4].

Table 2: Proteostasis Network Associations in Human Diseases

| Disease Category | Proteostasis Proteins in Disease Gene Sets | Most Perturbed PN Pathways | Characteristic Proteostasis State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodegenerative Diseases (AD, PD, FTD) | 30-35% | Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway (ALP), Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS), Proteostasis Regulation | Extensive UPS + Extracellular Proteostasis perturbation [6] |

| Cancers (Lung, Kidney, Pancreatic) | 25-36% | UPS, Proteostasis Regulation | Significant UPS perturbation, limited extracellular proteostasis involvement [6] |

| Autoimmune, Cardiovascular, Endocrine | 15-25% | Extracellular Proteostasis, ALP | Distinctive extracellular proteostasis deregulation, limited UPS involvement [6] |

Quantitative Analysis of Proteostasis in Neurodegeneration

Advanced mass spectrometry (MS) technologies have enabled comprehensive quantitative analysis of the PN in dementia research. Johnson et al. utilized label-free quantification to study >2000 brains across different cohorts including AD, Asymptomatic AD (AsymAD), and non-AD controls [4]. Other studies have obtained deeper proteome coverage using extensive peptide fractionation techniques on smaller cohorts [4]. These approaches have been instrumental in distinguishing proteome changes that respond to protein aggregates from those responsible for cognitive deficits by comparing AsymAD patients (with Aβ and tau pathology but normal cognition) with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) patients [4].

Key Experimental Findings

Chaperone Networks in AD: Inda et al. demonstrated that protein-protein interaction (PPI) chaperone networks were altered in AD human brains and mouse models using an affinity probe for stressed chaperones with label-free quantitation [4]. Spatial memory deficits were improved by inhibiting the formation of this stressed PPI network [4].

Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy (CMA): Bourdenx et al. used isobaric tags for quantitative proteomic analysis of insoluble brain fractions from CMA-deficient mice [4]. When crossed with AD mice, CMA deficiency enhanced insoluble proteins and exacerbated aggregation, whereas CMA activation decreased protein aggregation [4].

Endolysosomal Function: Lee et al. focused on SORLA, an endocytic receptor that mediates ELN trafficking [4]. Using isobaric tag quantitation on differentiated neurons from >50 iPSC lines of AD patients, they found SORLA expression significantly correlated with other AD risk factors localized to the ELN [4].

Diagram: Temporal Progression of Proteostasis Failure in Neurodegeneration vs. Cancer

Diagram Title: Temporal Proteostasis Perturbation Patterns

Experimental Methodologies for Proteostasis Research

Quantitative Proteomic Approaches

Mass Spectrometry (MS) Strategies:

- Label-Free Quantification: Used for large-scale studies (>2000 brains) to compare different cohorts (AD, AsymAD, Non-AD) [4]. This method measures peptide intensity without isotopic labeling, allowing analysis of numerous samples but with less accuracy than labeled methods.

- Isobaric Tag Quantitation (TMT/iTRAQ): Employed with extensive peptide fractionation for deeper proteome coverage in smaller cohorts [4]. Tags like tandem mass tags (TMT) enable multiplexing of samples, providing relative quantification across multiple conditions simultaneously.

- Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC): Metabolic labeling approach that incorporates heavy isotopes into proteins for accurate quantification, particularly useful in cell culture models.

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Mapping

- Immunoprecipitation (IP) of Endogenous Proteins: Traditional method requiring specific antibodies to isolate protein complexes from brain tissue, followed by MS analysis [4].

- Affinity Probes for Stressed Chaperones: Specialized probes that selectively bind to chaperones under stress conditions, enabling isolation and quantification of stressed PPI networks [4].

- Proximity Labeling (BioID/APEX): Engineered enzymes that biotinylate nearby proteins, allowing identification of transient protein interactions in live cells [4]. Particularly valuable for mapping interactions of endogenous proteins in native environments like neurons.

Model Systems for Dementia Research

- Post-mortem Human Brain Tissue: Provides direct evidence but represents end-stage disease often with comorbidities [4].

- Transgenic Mouse Models: Overexpress human genes associated with dementia, enabling study of discrete timepoints but creating potential artifacts [4].

- Knock-in Models: Newer approaches without overexpression that better model the influence of aging on proteostasis decline [4].

- Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-Derived Neurons: Patient-specific cells that can be differentiated into various neuronal and glial types, enabling drug screening combined with quantitative proteomics [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Proteostasis Network Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Isobaric Tags (TMT, iTRAQ) | Multiplexed quantitative proteomics | Relative protein quantification across multiple samples in PN studies [4] |

| Stable Isotope Labels (SILAC) | Metabolic labeling for accurate quantification | Tracking protein synthesis and degradation dynamics [4] |

| Affinity Probes for Stressed Chaperones | Selective isolation of stressed PPI networks | Mapping altered chaperone interactions in disease models [4] |

| Proximity Labeling Enzymes (BioID, APEX) | Identification of transient protein interactions | Mapping endogenous PPI in neurons for PN components [4] |

| iPSC Lines | Patient-specific disease modeling | Differentiating into neuronal subtypes for cell-type-specific PN studies [4] |

| Specific Chaperone Inhibitors/Activators | Modulating specific PN pathways | Testing functional roles of HSP70, HSP90, CMA in protein aggregation [4] |

Therapeutic Targeting of Proteostasis Networks

Current therapeutic approaches focus on modulating PN components to ameliorate proteinopathies. Several strategies have shown promise in preclinical models:

- Chaperone Modulation: Small molecule inhibitors of stress-induced PPI networks have improved spatial memory in AD mouse models [4].

- CMA Activation: Enhancing chaperone-mediated autophagy decreased protein aggregation in AD models, while CMA deficiency exacerbated pathology [4].

- ELN-Targeted Approaches: Modulating endolysosomal trafficking through receptors like SORLA represents a potential avenue given the strong genetic association of ELN components with AD risk [4].

- HSF1 Activation: Enhancing the heat shock response to boost chaperone expression represents another strategy to combat proteostasis collapse [1] [2].

However, translating these approaches to human therapies has proven challenging. The modest efficacy of current AD drugs targeting Aβ aggregates, coupled with the abundance of AsymAD cases, suggests that protein aggregates are necessary but not sufficient to cause dementia [4]. This underscores the need for better understanding of PN dysfunction in early disease stages and developing therapeutics that target the underlying proteostasis imbalance rather than just its aggregated end products.

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The future of PN research in neurodegenerative diseases requires several key developments:

- Direct PN Investigation: Quantitative proteomics needs to directly investigate the PN to understand its roles in the brain, aging, and dementia, using labeled strategies (heavy stable isotopes or isobaric tags) for better accuracy [4].

- Spatial Proteomics: Combining subcellular fractionation with PPI and post-translational modification analyses will determine how PN disruptions are distributed intracellularly [4].

- Cell-Type-Specific Resolution: New techniques to label cell-specific proteomes can quantify the cellular heterogeneity of the PN, understanding why certain neurons are more vulnerable [4].

- Comparative Studies: Quantitative proteomic comparisons of AD, FTD, and DLB are required to determine if therapeutic strategies can be universal or must be dementia-specific [4].

- Human-Relevant Models: Patient iPSCs differentiated into multiple neuronal and glial types will be essential for understanding cell-type-specific PN function and for drug screening [4].

The disappointing clinical trial outcomes for aggregate-targeting therapies in AD suggest that future success may require targeting earlier events in the proteostasis collapse cascade. As our understanding of PN architecture and regulation advances, particularly through quantitative proteomic approaches, new opportunities will emerge for therapeutic interventions that maintain or restore proteostasis balance in neurodegenerative diseases.

Key Misfolded Proteins in Major Neurodegenerative Disorders (Aβ, tau, α-synuclein, TDP-43, SOD1)

Neurodegenerative diseases represent one of the most significant challenges in modern medicine, with protein misfolding and aggregation serving as a central pathological hallmark across these conditions. More than 57 million people globally suffer from neurodegenerative diseases, a figure expected to double every 20 years [7]. The accumulation of misfolded proteins into toxic aggregates disrupts cellular homeostasis, triggers neuroinflammation, and ultimately leads to progressive neuronal loss [8] [9]. Despite their distinct clinical presentations, Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and other neurodegenerative conditions share common molecular mechanisms centered on protein misfolding [10] [11].

Understanding the structural properties, aggregation kinetics, and pathogenic mechanisms of key misfolded proteins—amyloid-β (Aβ), tau, α-synuclein, TDP-43, and SOD1—is crucial for developing targeted therapeutic strategies. These proteins, though functionally diverse in their native states, undergo conformational changes that expose hydrophobic regions, leading to the formation of soluble oligomers and ultimately insoluble fibrils and plaques [8] [9]. Recent research has highlighted the prion-like properties of these aggregates, enabling their propagation between cells and spreading pathology throughout connected brain regions [8] [10]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of these key misfolded proteins, their roles in disease pathogenesis, and the experimental approaches used to study them, framed within the context of protein misfolding and aggregation research.

Protein-Specific Pathogenesis and Characteristics

Table 1: Key Misfolded Proteins in Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Protein Name | Primary Associated Disease(s) | Aggregate Morphology & Key Characteristics | Genetic Loci | Key Pathogenic Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amyloid-β (Aβ) | Alzheimer's disease (AD) | Extracellular senile plaques; Aβ42 more aggregation-prone than Aβ40 | APP, PSEN1, PSEN2 | Soluble oligomers, fibrils |

| Tau | AD, Pick's disease, PSP, CBD, AGD, CTE | Intracellular neurofibrillary tangles; hyperphosphorylated forms | MAPT | Oligomers, paired helical filaments |

| α-Synuclein | Parkinson's disease (PD), Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB), Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) | Neuronal Lewy bodies; glial cytoplasmic inclusions in MSA | SNCA | Soluble oligomers, protofibrils, fibrils |

| TDP-43 | ALS, FTLD, AD (30-70% of cases) | Cytoplasmic inclusions; nuclear clearance; hyperphosphorylation | TARDBP | Oligomers, aggregates, C-terminal fragments |

| SOD1 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | Cytoplasmic inclusions in motor neurons; dismutase activity loss | SOD1 | Misfolded monomers, aggregates |

| Huntingtin | Huntington's disease (HD) | Intracellular inclusions with expanded polyglutamine tract | HTT | N-terminal fragments, oligomers |

Table 2: Quantitative Properties of Misfolded Protein Aggregates

| Protein | Native Structure | Aggregation-Prone Domains | Critical Concentration for Aggregation | Half-Life in CSF/Plasma | Key Post-Translational Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ | Disordered monomer | Central hydrophobic cluster (CHC) | ~5-20 μM (Aβ42) | ~2 hours (plasma) | Phosphorylation, truncation |

| Tau | Disordered microtubule-binding protein | Microtubule-binding repeats | ~50-100 nM | ~3 weeks (CSF) | Hyperphosphorylation, acetylation, truncation |

| α-Synuclein | Disordered/N-terminal lipid-binding | NAC domain (residues 61-95) | ~50-100 μM | ~2 days (CSF) | Phosphorylation (S129), truncation, ubiquitination |

| TDP-43 | RNA-binding protein with RRM domains | Prion-like domain (C-terminal) | Not well characterized | ~16 hours (CSF) | Hyperphosphorylation, proteolytic cleavage |

| SOD1 | Stable homodimer | Electrostatic loop elements | Mutation-dependent | ~24 hours (CSF) | Oxidation, misfolding of metal-free form |

Amyloid-β (Aβ)

Aβ peptides are proteolytic fragments of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), produced through sequential cleavage by β- and γ-secretases [8] [12]. While Aβ40 is the most abundant isoform in the brain, the Aβ42 isoform, although produced in smaller quantities, is most prone to misfolding and aggregation, resulting in cytotoxic prefibrillar oligomers and fibrils that accumulate as extracellular senile plaques [9]. The structural transition of Aβ from random coil to β-sheet-rich conformations is driven by exposed hydrophobic regions, particularly in the central hydrophobic cluster (residues 17-21) and C-terminal domain [8]. Soluble Aβ oligomers are now regarded as primary drivers of neurotoxicity, disrupting synaptic function through multiple mechanisms including binding to neuronal receptors, inducing oxidative stress, and triggering inflammatory responses [8] [11].

Aβ pathology follows a distinct spatial-temporal progression, beginning in cortical regions and spreading throughout the brain in a prion-like manner [8]. The propagation of Aβ aggregates involves template-induced conformational change, where misfolded Aβ acts as a seed to convert native proteins into pathological forms. This process occurs at molecular, cellular, and organ scales, facilitating disease progression [8]. Recent evidence also indicates cross-seeding interactions between Aβ and other pathological proteins, particularly tau, exacerbating overall pathology [11] [13].

Tau Protein

Tau is a microtubule-associated protein that normally stabilizes microtubule networks in neuronal axons. In disease states, tau becomes hyperphosphorylated, misfolds, and aggregates into intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) [8]. The transition from soluble to aggregated tau involves the formation of soluble oligomers that are highly toxic, followed by β-sheet-rich structures known as paired helical filaments (PHFs) that eventually form NFTs [8] [9]. Tau aggregation is promoted by numerous post-translational modifications, with hyperphosphorylation at specific epitopes (e.g., Ser202, Thr205, Thr231) serving as a key early event that reduces tau's affinity for microtubules and increases its aggregation propensity [13].

Tau pathology demonstrates a well-characterized progression through the brain, typically beginning in the transentorhinal region and advancing through hippocampal and cortical areas in a predictable pattern [8]. This spreading occurs through prion-like mechanisms where pathological tau seeds are released from affected cells and taken up by connected neurons, templating the misfolding of native tau in recipient cells [8] [10]. The molecular heterogeneity of tau aggregates contributes to different tauopathies, with distinct structural conformations or "strains" associated with specific diseases such as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration (CBD) [8].

α-Synuclein

α-Synuclein is a presynaptic protein that normally exists as an intrinsically disordered monomer but undergoes structural rearrangement to form β-sheet-rich aggregates that accumulate in Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites [8] [11]. The central non-amyloid-β component (NAC) region (residues 61-95) is critical for aggregation, with its hydrophobic nature driving the initial oligomerization [8]. The pathogenesis of α-synuclein in Parkinson's disease unfolds as a multistep process, initiating with protein misfolding that leads to the formation of increasingly intricate oligomers, soluble intermediates, and eventually insoluble fibrils and aggregates [11].

The prion-like propagation of α-synuclein pathology follows a characteristic pattern through the nervous system, beginning in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and olfactory bulb, then spreading through the brainstem to midbrain and cortical regions [8]. This spreading occurs through cell-to-cell transmission involving the release of α-synuclein aggregates from donor cells, their uptake by recipient cells, and subsequent seeding of new aggregates [8] [10]. The aggregates of α-synuclein have the potential to induce atrophy through diverse mechanisms, encompassing lysosomal impairment, mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and dysfunction in synaptic transmission [11].

TDP-43

TDP-43 is an RNA/DNA binding protein that normally resides predominantly in the nucleus but in disease conditions mislocalizes to the cytoplasm where it forms hyperphosphorylated and ubiquitinated aggregates [8] [13]. The protein contains two RNA recognition motifs (RRM1 and RRM2) and a C-terminal domain with a prion-like glycine-rich region that mediates protein-protein interactions and drives aggregation [13]. Pathological TDP-43 is characterized by hyperphosphorylation (particularly at Ser409/410), proteolytic cleavage generating C-terminal fragments (~25-35 kDa), and loss of nuclear function [13].

In approximately 30-70% of Alzheimer's disease cases, TDP-43 co-aggregates with Aβ and tau, with patients exhibiting more severe cognitive impairment, faster disease progression, and greater hippocampal atrophy [13]. TDP-43 interacts with both major AD pathologies: it promotes Aβ oligomerization and directly influences tau pathology by regulating tau mRNA stability and alternative splicing [13]. TDP-43 also disrupts mitochondrial function, RNA metabolism, and protein quality control, creating a vicious cycle of proteostatic collapse [9] [13].

SOD1

Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) is a homodimeric metalloenzyme that catalyzes the conversion of superoxide radicals to oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. Mutations in the SOD1 gene, particularly those that destabilize the native structure or reduce metal binding, promote misfolding and aggregation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [10] [12]. Misfolded SOD1 species lose their dismutase activity and acquire toxic gain-of-function properties, including pro-oxidant activity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impairment of protein quality control systems [10].

SOD1 aggregates propagate in a prion-like manner, with misfolded SOD1 acting as a template to convert native SOD1 into pathological forms [8] [10]. These aggregates can spread between cells and induce misfolding of native SOD1, highlighting the role of prion-like mechanisms in the progression of ALS [8]. The accumulation of SOD1 aggregates disrupts proteostasis by saturating chaperone systems and impairing proteasomal and autophagic clearance pathways, leading to widespread protein dyshomeostasis [10].

Common Aggregation Mechanisms and Cross-Talk

Despite their structural differences, the pathogenic proteins share common aggregation mechanisms including nucleation-dependent polymerization, where the formation of an initial seed represents the rate-limiting step, followed by rapid elongation and amplification [8] [9]. Each protein can form multiple structurally distinct aggregates or "strains" that exhibit different pathological properties, seeding activities, and disease phenotypes [8]. This conformational diversity may explain the heterogeneity in clinical presentations and disease progression rates observed in patients.

Growing evidence indicates significant cross-talk between different pathological proteins. The accumulation of one misfolded protein can impair the entire proteostatic network, triggering the misfolding of unrelated proteins that would otherwise fold normally [10]. For instance, Aβ can promote tau hyperphosphorylation and aggregation, while TDP-43 pathology interacts with both Aβ and tau to exacerbate Alzheimer's pathology [11] [13]. These interactions create vicious cycles that accelerate disease progression and complicate therapeutic targeting.

Diagram 1: Protein Misfolding and Propagation. The diagram illustrates the molecular events in protein misfolding, from initial native structure to oligomer formation, fibril elongation, and intercellular propagation through seeding. Toxic oligomers (yellow) directly cause neuronal dysfunction, while the cyclic process of fragmentation and templating enables disease progression.

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Aggregate Detection and Characterization

Immunoassay-Based Detection (ELISA/Simoa) Protocol Principle: Sandwich immunoassays enable specific detection and quantification of target proteins and their aggregated forms in biological fluids and tissue extracts. Detailed Methodology:

- Coating: Coat microplate wells with capture antibodies specific for target protein epitopes (e.g., 6E10 for Aβ, AT8 for phosphorylated tau, Syn211 for α-synuclein).

- Blocking: Block nonspecific binding sites with protein-based blockers (5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in PBS-Tween).

- Sample Preparation: Dilute CSF/plasma/tissue homogenates in appropriate buffers. For aggregate-specific detection, use native conditions without denaturation.

- Incubation: Add samples and standards to wells, incubate 2-4 hours at room temperature with shaking.

- Detection: Add biotinylated detection antibody (targeting distinct epitope), incubate 1-2 hours.

- Signal Development: Add streptavidin-HRP conjugate, incubate 30-60 minutes, then add chemiluminescent or colorimetric substrate.

- Quantification: Measure signal intensity and calculate concentrations from standard curves. Technical Notes: For ultrasensitive detection, use Single Molecule Array (Simoa) technology with paramagnetic beads and enzyme-labeled detection antibodies for digital counting of individual molecules [14].

Seeding Amplification Assays (RT-QuIC) Protocol Principle: Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion assays exploit the prion-like seeding activity of protein aggregates to amplify minute quantities for detection. Detailed Methodology:

- Recombinant Substrate: Express and purify recombinant full-length target protein (e.g., α-synuclein, tau) in E. coli.

- Sample Preparation: Dilute CSF/brain homogenate in PBS with 0.1% SDS to dissociate non-specific aggregates while preserving seeding-competent species.

- Reaction Setup: Mix sample with recombinant substrate (0.1-0.3 mg/mL) in black 96-well plates with glass beads.

- Cyclic Incubation: Incubate plates at 37-42°C with intermittent shaking cycles (e.g., 1 minute shaking, 14 minutes rest).

- Thioflavin T Monitoring: Include 10-20 μM Thioflavin T, monitor fluorescence (excitation 450 nm, emission 480 nm) after each cycle.

- Data Analysis: Determine amplification time and maximum fluorescence; compare to standards for semi-quantification. Technical Notes: Assay conditions must be optimized for each protein target; α-synuclein RT-QuIC typically requires 150-200 cycles, while tau assays may need different buffer conditions [8] [14].

Cellular and Animal Models

Primary Neuronal Cultures for Toxicity Assessment Protocol Principle: Utilize primary neurons to evaluate the direct neurotoxic effects of protein aggregates and screen therapeutic compounds. Detailed Methodology:

- Cortical/Hippocampal Dissection: Isolate brain regions from E16-18 rodent embryos or postnatal day 0-1 pups.

- Tissue Dissociation: Digest tissue with papain or trypsin, triturate to single-cell suspension.

- Culture Establishment: Plate cells on poly-D-lysine-coated plates in neurobasal medium with B27 supplement, glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin.

- Treatment Preparation: Prepare recombinant oligomers (Aβ, α-synuclein, tau) by agitating monomer solutions at 300-1000 rpm for 12-48 hours; characterize by AFM/TEM and SEC.

- Compound Testing: Pre-treat neurons with experimental compounds 2-24 hours before adding protein aggregates.

- Viability Assessment: After 24-72 hours exposure, measure cell viability using MTT reduction, LDH release, or live/dead staining.

- Functional Assays: Assess mitochondrial membrane potential (JC-1 dye), reactive oxygen species (DCFDA), synaptic density (immunostaining for PSD-95, synapsin). Technical Notes: Use 7-14 days in vitro (DIV) neurons for maturity; include both monomer and vehicle controls [8] [11].

Transgenic Mouse Models Protocol Principle: Engineer mice to express human mutant proteins to recapitulate key aspects of protein aggregation pathology. Detailed Methodology:

- Model Selection: Choose appropriate models - APP/PS1 for Aβ pathology, P301S for tauopathy, A53T for α-synuclein, SOD1G93A for ALS.

- Genotyping: Confirm transgene presence by PCR of tail DNA.

- Intervention Studies: Administer test compounds via oral gavage, intraperitoneal injection, or intracerebroventricular infusion starting pre-symptomatically or at early disease stages.

- Behavioral Assessment: Conduct motor tests (rotarod, open field) and cognitive tests (Morris water maze, Y-maze) at regular intervals.

- Tissue Collection: Perfuse animals transcardially with PBS, collect brains and spinal cords for fixed (4% PFA) and fresh-frozen processing.

- Pathological Analysis: Perform immunohistochemistry for protein aggregates, stereological cell counting, biochemical fractionation for soluble/insoluble proteins. Technical Notes: Include age-matched non-transgenic and vehicle-treated controls; power studies appropriately for group sizes (n=10-15) [10] [11].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | 6E10 (Aβ), AT8/Tau5 (tau), Syn211 (α-syn), 2E2-D3 (TDP-43 pS409/410) | IHC, WB, ELISA, immunoprecipitation | Validate specificity for aggregated vs. monomeric forms |

| Assay Kits | Human Aβ42 ELISA, p-tau181 Simoa, α-syn RT-QuIC, TDP-43 MSD | Biomarker quantification, aggregate detection | Consider matrix effects in biological fluids |

| Cell Lines | SH-SY5Y, HEK293, BV-2 microglia, primary neuronal cultures | Toxicity screening, mechanism studies | Use relevant models (primary neurons for physiological relevance) |

| Animal Models | APP/PS1 (AD), P301S (tauopathy), A53T (α-syn), SOD1G93A (ALS) | Pathogenesis studies, therapeutic testing | Account for species differences in protein sequences |

| Recombinant Proteins | Monomeric Aβ1-42, α-synuclein, tau (2N4R, 1N4R), TDP-43 full-length | Biophysical studies, seeding assays | Ensure proper purification and characterization of conformation |

Biomarker Applications and Therapeutic Strategies

Table 4: Biomarker and Therapeutic Development Pipeline

| Target/Pathway | Biomarker Status | Therapeutic Approaches | Clinical Trial Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ aggregation | Plasma Aβ42/40 ratio (CLIA-approved) | Monoclonal antibodies (Lecanemab, Donanemab), BACE inhibitors | Phase 3 completed/ongoing |

| Tau pathology | CSF p-tau181, p-tau217 (validated) | Anti-tau antibodies, tau aggregation inhibitors, ASOs | Phase 2-3 trials |

| α-Synuclein aggregation | RT-QuIC (CSF, tissue), seed amplification assays | Immunotherapies, ASOs, small molecule inhibitors | Phase 1-2 studies |

| TDP-43 pathology | Plasma NfL (non-specific), CSF TDP-43 fragments | RNA-targeting therapies, modulation of nucleocytoplasmic transport | Preclinical/early clinical |

| Microglial function | sTREM2 (CSF), microglial PET imaging | TREM2 agonists (AL002, VG-3927), CD33 modulation | Phase 1-2 trials |

Biomarker Development

Fluid biomarkers have transformed neurodegenerative disease research and clinical trials by providing objective measures of pathological processes [14] [7]. Blood-based biomarkers offer particular promise for scalable screening and longitudinal monitoring. The most established biomarkers include:

- Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio: Decreased ratio indicates amyloid pathology; measured using immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry or immunoassays [14]

- Phosphorylated tau (p-tau181, p-tau217): Highly specific for Alzheimer's tau pathology; strong correlation with tau PET [14]

- Neurofilament light chain (NfL): Non-specific marker of neuroaxonal damage; elevated across multiple neurodegenerative conditions [14] [7]

- sTREM2: Marker of microglial activation; shows dynamic changes during disease progression [15]

Recent technological advances including single-molecule array (Simoa) and mass spectrometry-based methods have enabled precise quantification of these biomarkers in blood, overcoming previous sensitivity limitations [14]. The Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium (GNPC) has established one of the world's largest harmonized proteomic datasets, including approximately 250 million unique protein measurements from over 35,000 biofluid samples, accelerating biomarker discovery and validation [7].

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Protein Aggregation

Immunotherapy Approaches Monoclonal antibodies represent the most advanced therapeutic strategy targeting protein aggregates. Lecanemab, Aducanumab, and Donanemab target Aβ aggregates with varying epitope specificities, demonstrating clearance of amyloid plaques [15]. These antibodies work primarily by enhancing microglial phagocytosis of aggregates through Fc receptor engagement [15]. Similar approaches are being developed for α-synuclein (Prasinezumab) and tau (Gosuranemab, Tilavonemab) [11]. Challenges include limited blood-brain barrier penetration, potential inflammatory side effects (ARIA with anti-Aβ antibodies), and targeting of appropriate protein species [15].

Small Molecule Inhibitors Small molecules targeting various stages of the aggregation cascade include:

- Aggregation inhibitors: Compounds like epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and CLR01 that block the initial oligomerization steps

- Protein clearance enhancers: Activators of autophagy (rapamycin analogs) or the ubiquitin-proteasome system

- Chaperone inducers: Compounds that boost cellular chaperone networks (arimoclomol, celastrol)

- Kinase inhibitors: Modulators of kinases involved in pathological phosphorylation (GSK-3β, CK1δ inhibitors for tau) [11] [13]

Novel Mechanistic Approaches Emerging strategies include:

- Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs): Reduce production of target proteins; Tofersen for SOD1-ALS shows clinical benefit [10]

- Gene therapy: AAV-mediated delivery of protective factors (BDNF, PGRN) or knockdown of mutant genes

- Modulation of protein quality control systems: Enhancement of proteasome function, autophagy, or the unfolded protein response [11]

- Microglial-targeted therapies: TREM2 agonists (AL002, VG-3927), CD33 antagonists that enhance clearance of protein aggregates [15]

Diagram 2: Therapeutic Targeting of Protein Aggregation. The diagram illustrates key intervention points in the protein aggregation cascade, including ASOs to reduce synthesis, small molecules to inhibit oligomerization, immunotherapies to clear fibrils, and microglial modulators to address neuroinflammation. Enhancing proteostasis machinery (green) represents another key therapeutic strategy.

The study of misfolded proteins in neurodegenerative diseases has progressed dramatically from initial histopathological observations to sophisticated molecular understanding of aggregation mechanisms and their consequences. Key challenges remain, including the need for biomarkers that can detect pathology in the earliest stages, therapies that can effectively target the most toxic species, and strategies to address the heterogeneity of these diseases.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Early intervention strategies: Targeting pathological processes before irreversible neuronal loss occurs

- Combination therapies: Addressing multiple aspects of the disease cascade simultaneously

- Patient stratification: Using biomarker profiles to match patients with optimal treatments

- Novel therapeutic modalities: Developing approaches that target RNA, enhance protein clearance, or modulate neuroinflammation

- Advanced delivery systems: Ensuring therapeutics reach the appropriate brain regions and cell types

The integration of multi-omics technologies, advanced imaging, and sophisticated cellular models will continue to deepen our understanding of these complex diseases. International collaborative efforts like the Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium are essential for assembling the large datasets needed to identify robust biomarkers and therapeutic targets [7]. As our knowledge of protein misfolding mechanisms grows, so does the potential for developing effective treatments that can alter the course of these devastating disorders.

The seeding-nucleation model of protein aggregation represents a fundamental mechanism underlying the pathogenesis of numerous neurodegenerative diseases. This process involves the transition of native monomeric proteins into toxic oligomeric species and eventually into amyloid fibrils, driven by a nucleation-dependent polymerization mechanism. The formation of stable nucleation seeds constitutes the rate-limiting step, after which rapid elongation and amplification occur through prion-like template-directed misfolding. This comprehensive review examines the molecular mechanisms, kinetic principles, and experimental methodologies for studying protein aggregation, with particular emphasis on the central role of oligomeric intermediates in neurotoxicity. Emerging therapeutic strategies targeting specific stages of the aggregation cascade are also discussed, providing a framework for developing interventions against protein misfolding disorders.

Protein aggregation following the seeding-nucleation model is a central pathological feature in neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), Huntington's disease (HD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [16] [17]. These conditions are characterized by the accumulation of specific misfolded proteins—such as amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau in AD, α-synuclein (α-syn) in PD, and huntingtin (Htt) in HD—that form protein aggregates disrupting cellular homeostasis and ultimately leading to neuronal death [16] [17] [18].

The seeding-nucleation mechanism was first described for prion proteins (PrP) and has since been recognized as a fundamental process underlying the aggregation kinetics of numerous amyloidogenic proteins implicated in neurodegeneration [19] [18]. This model explains the characteristic lag phase observed during in vitro aggregation assays, where soluble monomers slowly form stable nucleation seeds, followed by a rapid growth phase where these seeds template the conversion of additional monomers into fibrillar structures [19] [18].

Understanding the molecular events governing the transition from monomers to oligomers is particularly crucial, as accumulating evidence indicates that soluble oligomeric species—rather than mature fibrils—represent the primary mediators of neurotoxicity in protein misfolding disorders [17] [18]. These oligomers exhibit heightened toxicity through multiple mechanisms, including membrane disruption, mitochondrial dysfunction, impairment of proteostatic systems, and induction of oxidative stress [18].

This review comprehensively examines the seeding-nucleation model of protein aggregation within the context of neurodegenerative disease research, with emphasis on molecular mechanisms, experimental approaches, and therapeutic implications.

Molecular Mechanisms of Seeding-Nucleation

The Kinetic Pathway of Aggregation

The aggregation of amyloidogenic proteins follows a characteristic kinetic trajectory comprising three distinct phases: lag phase, elongation phase, and plateau phase. During the initial lag phase, soluble monomers undergo conformational changes and associate into unstable oligomeric intermediates until critical nuclei form. This nucleation step is rate-limiting and stochastic, explaining the variable onset of aggregation observed experimentally [18]. Once stable seeds are established, the process enters a rapid elongation phase where these seeds act as templates for the sequential addition of monomers, leading to exponential growth of fibrillar structures. Finally, the system reaches a plateau phase as the available monomer pool depletes and equilibrium establishes between soluble and insoluble species [17] [18].

The diagram below illustrates the sequential stages of the seeding-nucleation model:

Oligomeric Intermediates: Structure and Toxicity

Oligomeric assemblies formed during the aggregation process represent crucial intermediates with distinct structural and toxic properties. These species are typically characterized by their amorphous structures with exposed hydrophobic regions, making them highly reactive and cytotoxic [17]. Oligomers exist in a dynamic equilibrium with monomers and fibrils, and can be categorized as either "on-pathway" (progressing toward fibril formation) or "off-pathway" (terminal products that do not convert to fibrils) [17].

The structural transition from disordered monomers to β-sheet-rich oligomers constitutes a critical step in the aggregation process. In environments with limited solvent availability, such as those mimicked by reverse micelles, monomeric amyloid-β (Aβ) proteins can form extended β-strands, providing a plausible mechanism for amyloid fibril nucleation in the brain [17]. This structural transformation is initiated by the formation of β-strand seed structures that act as nucleation sites for further aggregation.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that soluble oligomers from various amyloidogenic proteins (Aβ, α-syn, tau) exhibit greater correlation with disease progression and neuronal dysfunction than mature fibrils or insoluble deposits [17] [18]. The mechanisms underlying oligomer toxicity include:

- Membrane disruption through pore formation or bilayer distortion

- Mitochondrial dysfunction and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production

- Impairment of synaptic plasticity and neuronal signaling

- Disruption of proteostasis by overwhelming protein quality control systems

- Induction of inflammatory responses in glial cells

Table 1: Characteristics of Oligomeric Species in Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Protein | Size Range | Key Structural Features | Primary Toxic Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ | 10-50 monomers | Prefibrillar assemblies with exposed hydrophobic patches | Membrane disruption, synaptic dysfunction, oxidative stress |

| α-Synuclein | 10-30 monomers | Annular protofibrils with β-sheet content | Mitochondrial impairment, membrane permeability, vesicle trafficking disruption |

| Tau | 10-40 monomers | Aggregates with cross-β structure | Microtubule destabilization, impaired axonal transport |

| Huntingtin | 10-100 monomers | Spherical and annular structures with polyQ expansion | Proteasome inhibition, transcription dysregulation, organelle dysfunction |

Prion-like Propagation and Cell-to-Cell Transmission

A defining characteristic of many pathogenic protein aggregates is their capacity for prion-like propagation, enabling the spread of pathology throughout the brain [19] [17] [18]. This process involves the release of misfolded proteins from donor cells, their uptake by recipient cells, and subsequent seeding of new aggregates in previously healthy cells [19] [17].

The molecular mechanisms facilitating cell-to-cell transmission include:

- Non-classical secretion of aggregated proteins via exocytotic vesicles [19]

- Exosome-mediated transfer of pathogenic species between cells [19] [17]

- Receptor-mediated endocytosis of extracellular aggregates [19]

- Direct penetration of plasma membranes by oligomeric species [19]

The following diagram illustrates the prion-like propagation mechanism:

The seeding efficiency of pathogenic aggregates depends on multiple factors, including their structural properties (strain characteristics), cellular environment, and the presence of co-factors that can either promote or inhibit the process [18]. Different conformational variants (strains) of the same protein can exhibit distinct seeding activities and neuropathological profiles, potentially explaining the heterogeneity in clinical presentations and disease progression observed among patients with the same neuropathological diagnosis [17] [18].

Experimental Methods and Research Tools

Label-Free Detection of Protein Aggregates

Traditional approaches for visualizing protein aggregates rely on fluorescent tags (e.g., GFP, YFP, mCherry) fused to the protein of interest. However, these tags can significantly alter the biophysical properties of proteins, including aggregation kinetics, final aggregate structure, and interactions with cellular components [20]. For instance, GFP-tagged huntingtin exon 1 (Httex1) forms fibrils approximately 3 nm thicker than untagged Httex1 and exhibits altered mechanical properties and interactomes [20].

To address these limitations, label-free methods have been developed that enable the study of unaltered protein aggregates:

- Label-free Identification of NDD-associated Aggregates (LINA): Utilizes deep learning to detect unlabeled protein aggregates in living cells from transmitted-light images, allowing quantitative analysis of aggregation dynamics without fluorescent labeling [20]

- Quantitative Phase Imaging (QPI): Produces quantitative images of unlabeled specimens based on phase shifts, enabling extraction of parameters such as dry mass and morphology with minimal photodamage [20]

- Brillouin Microscopy: A non-invasive technique that studies biomechanical properties of cells and tissues through inelastic scattering, revealing that protein aggregates exhibit higher longitudinal modulus compared to cytoplasm [21]

- Self-driving microscopy: Employs deep learning to predict aggregation onset from images of soluble protein, achieving 91% accuracy in triggering optimized multimodal imaging when aggregation is imminent [21]

The experimental workflow for label-free aggregate detection is summarized below:

Quantitative Assessment of Aggregation Kinetics

The table below summarizes key parameters and methods for quantifying protein aggregation kinetics:

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for Protein Aggregation Analysis

| Parameter | Description | Measurement Techniques | Typical Values/Ranges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lag Phase Duration | Time required for nucleation seed formation | Thioflavin T fluorescence, light scattering | Minutes to hours (in vitro); days in cellular models |

| Elongation Rate | Speed of fibril growth after nucleation | Atomic force microscopy, TEM with time-lapse | Variable depending on protein and conditions |

| Oligomer Concentration | Amount of soluble oligomeric species | ELISA, native PAGE, photo-induced cross-linking | Nanomolar to low micromolar range in disease models |

| Seeding Efficiency | Potency in inducing aggregation in recipient cells | FRET-based biosensors, cell-based seeding assays | Strain-dependent; affected by aggregate size and structure |

| Toxicity Threshold | Oligomer concentration causing cell death | Viability assays, membrane integrity tests | Protein-specific; often correlates with oligomer size |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines essential research tools and reagents for studying protein aggregation:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Aggregation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Proteins | Aβ1-42, α-synuclein, tau isoforms | In vitro aggregation studies, seeding assays | Source, purification method, endotoxin levels affect reproducibility |

| Pre-formed Fibrils (PFFs) | α-syn PFFs, tau PFFs | Seeding experiments in cellular and animal models | Preparation method, sonication protocol, concentration |

| Fluorescent Tags | GFP, mCherry, SNAP-tag | Visualizing aggregation in live cells | Tags can alter native aggregation kinetics and properties |

| Aggregation Sensors | Thioflavin T, Congo red, Proteostat | Detecting amyloid formation in vitro and in cells | Specificity, background signal, compatibility with live cells |

| Cell Lines | SH-SY5Y, HEK293, primary neurons | Cellular models of protein aggregation | Species origin, differentiation state, transfection efficiency |

| Animal Models | APP/PS1 mice, Thy1-α-syn mice, HD knock-in | In vivo study of aggregation and spread | Genetic background, age of onset, pathological progression |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Seeding Assay Using Pre-formed Fibrils (PFFs)

Purpose: To evaluate the seeding activity of pre-formed fibrils on endogenous soluble proteins in cellular models.

Materials:

- Purified pre-formed fibrils (PFFs) of protein of interest (e.g., α-syn, tau)

- Target cell line (e.g., HEK293 cells, primary neurons)

- Lipofectamine or alternative transfection reagent (for some protocols)

- Fixation and immunostaining reagents

- Confocal microscopy equipment

Procedure:

- Prepare PFFs by sonicating fibril stocks (3 × 10 seconds pulses at 10-20% amplitude) to generate short fragments suitable for cellular uptake.

- Treat cells with PFFs at appropriate concentration (typically 0.1-5 μg/mL) for 4-24 hours.

- Remove extracellular PFFs by washing with PBS and maintain cells in fresh media for desired time period (typically 3-14 days).

- Fix cells and perform immunostaining for protein of interest and aggregation markers (e.g., phospho-epitopes).

- Image using confocal microscopy and quantify percentage of cells with aggregates, aggregate number per cell, and aggregate size.

Key Considerations: PFF concentration, sonication parameters, and cell type significantly impact seeding efficiency. Include appropriate controls (monomer-treated cells, vehicle-only) in each experiment [19].

Protocol: Label-Free Identification of Aggregates in Living Cells

Purpose: To detect and quantify protein aggregates in living cells without fluorescent labeling.

Materials:

- Cells expressing protein of interest (without fluorescent tag)

- Microscope with transmitted-light or phase-contrast capability

- LINA software and pre-trained neural network models [20]

- Computer with appropriate GPU for deep learning analysis

Procedure:

- Culture cells expressing untagged protein of interest under appropriate conditions.

- Acquire transmitted-light image stacks at multiple z-planes using microscope.

- Process images using Fourier filtering to generate quantitative phase images (QPI).

- Apply LINA deep learning model to identify aggregates from phase images.

- Quantify aggregate parameters including number, area, dry mass, and growth kinetics.

Key Considerations: The method is robust across imaging conditions and different protein constructs, providing high-speed, specific identification of native aggregates without tag-induced alterations [20].

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The seeding-nucleation model provides critical insights for developing therapeutic strategies targeting protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases. Current approaches include:

- Seeding inhibitors: Compounds that prevent the template-directed conversion of native proteins (e.g., small molecules that bind to oligomeric species) [16] [17]

- Passive immunotherapy: Antibodies targeting toxic oligomeric species to neutralize their toxicity and promote clearance [16] [17]

- Enhancement of protein clearance: Activation of autophagy-lysosomal pathway or ubiquitin-proteasome system to degrade aggregates [16]

- Gene therapy: Reduction of mutant protein expression using antisense oligonucleotides or RNA interference [16] [17]

Understanding the precise molecular mechanisms underlying the formation and propagation of pathogenic seeds continues to drive innovation in diagnostic and therapeutic development for neurodegenerative proteinopathies. The emergence of advanced imaging technologies and label-free detection methods promises to accelerate these efforts by providing more physiologically relevant insights into protein aggregation dynamics.

Protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, is essential for neuronal function and survival. It encompasses the coordinated cellular processes that regulate protein synthesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation [10] [22]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the autophagy-lysosome pathway (ALP) represent the two major intracellular protein degradation systems responsible for maintaining this delicate balance [23] [24]. In neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), Huntington's disease (HD), and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), the accumulation of misfolded and aggregated proteins is a defining pathological feature [10] [16] [11]. This failure in proteostasis is often attributed to impairments in the UPS and ALP, which become overwhelmed by the burden of aberrant proteins or are directly compromised by the disease process itself [23] [10] [11]. A comprehensive understanding of these clearance pathways, their intricate crosstalk, and their role in neurodegeneration is paramount for developing novel therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring proteostatic control and neuronal health.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS)

Molecular Mechanism and Components

The UPS is a highly specific, ATP-dependent proteolytic system responsible for the degradation of the majority of intracellular soluble proteins, particularly short-lived and soluble misfolded proteins [23] [25]. It operates through a coordinated two-step process: the covalent attachment of ubiquitin chains to a target protein, followed by its recognition and degradation by the proteasome [22] [24].

Ubiquitination is a enzymatic cascade involving three key components:

- E1 (Ubiquitin-activating enzyme): Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner [24] [25].

- E2 (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme): Accepts the activated ubiquitin from E1 [24] [25].

- E3 (Ubiquitin ligase): Recognizes specific substrate proteins and facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to the target protein, conferring substrate specificity. The human genome encodes hundreds of E3 ligases, allowing for precise targeting [22] [24] [25].

Proteins tagged with chains of ubiquitin linked through lysine 48 (K48) are typically directed to the proteasome for degradation [25]. The proteasome is a multi-subunit complex comprising a 20S core particle (CP) and one or two 19S regulatory particles (RP) [22]. The 19S RP recognizes ubiquitinated proteins, removes the ubiquitin chains, and unfolds the substrate. The unfolded polypeptide is then translocated into the 20S CP, a barrel-shaped structure containing proteolytic active sites that hydrolyze the protein into short peptides [22] [24].

Figure 1: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Pathway. This diagram illustrates the sequential enzymatic cascade of ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of a target protein.

The UPS in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Impairment of the UPS is heavily implicated in the pathogenesis of various neurodegenerative diseases. Protein aggregates enriched with ubiquitinated proteins are a hallmark of these disorders, suggesting a failure in UPS-mediated clearance [10] [11]. In cerebral ischemia, for example, ubiquitinated proteins accumulate, and proteasome function is compromised [23]. The depletion of free ubiquitin and the accumulation of its mutant form can directly inhibit the UPS, contributing to delayed neuronal death [23].

Specific disease-associated proteins are also linked to UPS dysfunction:

- In Parkinson's disease, mutations in E3 ubiquitin ligases like Parkin are associated with familial forms of the disease. Parkin promotes the degradation of proteins like Drp1, and its loss of function exacerbates neuronal injury [23].

- In Alzheimer's disease, components of the UPS are found associated with neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques [10].

- The immunoproteasome, a specialized proteasome induced during inflammation, is upregulated in cerebral ischemia. Its inhibition has been shown to reduce infarction volume and attenuate inflammation, suggesting a role in ischemic pathology [23].

Table 1: Key UPS Components and Their Alterations in Neurodegenerative Pathologies

| UPS Component | Normal Function | Alteration in Disease | Associated Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|

| E3 Ligase (Parkin) | Substrate ubiquitination | Loss-of-function mutations | Parkinson's Disease [23] |

| E3 Ligase (TRAF6) | Signal transduction | Overexpression exacerbates injury | Cerebral Ischemia [23] |

| Immunoproteasome | Immune response, stress clearance | Subunit (β1i, β5i) upregulation | Cerebral Ischemia, Stroke [23] |

| Deubiquitinase (USP14) | Negatively regulates proteasome | Inhibition is neuroprotective | Cerebral Ischemia [23] |

| Ubiquitin C-terminal Hydrolase L1 (UCHL1) | Deubiquitination | Mutation (C152A) is protective | Ischemic Stroke [23] |

The Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway (ALP)

Molecular Mechanism and Forms of Autophagy

The ALP is responsible for the degradation of long-lived proteins, insoluble protein aggregates, and damaged organelles [23] [25]. It is a vesicular trafficking pathway that delivers cargo to the lysosome for degradation. There are three main forms of autophagy:

- Macroautophagy: The primary form, involving the formation of a double-membraned vesicle, the autophagosome, which engulfs cytoplasmic cargo. The autophagosome then fuses with the lysosome to form an autolysosome, where the contents are degraded by acidic hydrolases [24] [25].

- Microautophagy: The direct engulfment of cytoplasmic material by invagination of the lysosomal membrane.

- Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy (CMA): A highly selective process where specific proteins bearing a KFERQ-like motif are recognized by chaperones (Hsc70) and directly translocated across the lysosomal membrane via the LAMP-2A receptor for degradation [11].

Lysosomes can also receive extracellular material and cell-surface receptors via endocytosis, phagocytosis, and pinocytosis [24] [25].

Figure 2: The Macroautophagy Pathway. This diagram illustrates the key stages of macroautophagy, from the formation of the phagophore to the degradation of cargo within the autolysosome.

The ALP in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Similar to the UPS, the ALP is critically impaired in neurodegenerative diseases. The accumulation of autophagic vesicles is a common observation in affected neurons, indicating a blockage in the autophagic flux [11] [26]. Many disease-linked aggregate-prone proteins, such as mutant huntingtin (in HD) and α-synuclein (in PD), are substrates for autophagy, and their clearance is heavily dependent on a functional ALP [10] [11].

Specific disease connections include:

- In Parkinson's disease, α-synuclein aggregates can impair CMA by binding to and obstructing the LAMP-2A receptor, thereby inhibiting its own degradation and that of other CMA substrates [11].

- In Alzheimer's disease, defective autophagy contributes to the accumulation of Aβ peptides and hyperphosphorylated tau. Enhancing autophagy has been shown to reduce pathology in animal models [11] [26].

- In cerebral ischemia, the autophagy-lysosome pathway is impaired, contributing to neuronal damage [23].

Table 2: Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway Impairments in Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Disease | Key Aggregated Protein(s) | ALP Impairment |

|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | Amyloid-β, Tau | Reduced autophagosome clearance, disrupted lysosomal function [11] [26] |

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) | α-Synuclein | Inhibition of Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy (CMA), impaired mitophagy [11] |

| Huntington's Disease (HD) | Mutant Huntingtin (mHtt) | Defective cargo recognition and autophagosome transport [10] |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) | TDP-43, SOD1 | Impaired autophagic flux, lysosomal dysfunction [10] [12] |

| Cerebral Ischemia | Various ubiquitinated proteins | Impaired autophagy-lysosome pathway [23] |

Crosstalk and Therapeutic Targeting

Interplay Between UPS and ALP

The UPS and ALP are not isolated systems but are interconnected and collaborate to maintain proteostasis. When one pathway is compromised, the other can often compensate. For instance, proteasome inhibition can induce the upregulation of autophagy [26]. Conversely, impairment in autophagy can lead to increased dependence on the UPS. This crosstalk becomes critical under conditions of cellular stress, such as in neurodegenerative diseases where the burden of misfolded proteins overwhelms both systems, leading to a vicious cycle of proteostatic collapse [23] [11] [26]. The Keap1-Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway is one example of a regulatory node that can be activated by proteotoxic stress and can transcriptionally upregulate components of both degradation systems [11].

Experimental Protocols for Studying Clearance Pathways

Protocol 1: Assessing Proteasome Activity in Cell Cultures

- Cell Treatment: Treat cultured neuronal cells (e.g., SH-SY5Y, primary neurons) with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG-132, 10 μM) as a negative control or a potential activator (e.g, Trehalose) for a defined period (e.g., 6-24 h) [23] [10].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in a buffer containing ATP to maintain 26S proteasome integrity.

- Activity Assay: Use fluorogenic peptides that are substrates for different proteasome catalytic activities (e.g., Suc-LLVY-AMC for chymotrypsin-like activity). Incubate cell lysates with the substrate and measure the release of the fluorescent group (AMC) over time using a microplate reader [22].

- Data Analysis: Normalize fluorescence values to total protein concentration. Activity is expressed as fluorescence intensity/hour/mg of protein.

Protocol 2: Monitoring Autophagic Flux Using LC3-I/II Turnover

- Transfection/Treatment: Transfect cells with a GFP-LC3 plasmid or treat cells with an autophagy modulator (e.g., Rapamycin for induction, Bafilomycin A1 for inhibition of lysosomal degradation) [24].

- Protein Extraction and Western Blot: Harvest cells and extract proteins. Perform Western blot analysis using antibodies against LC3.

- Detection and Quantification: LC3-I (cytosolic form) and the phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated LC3-II (autophagosome-associated form) will be detected. An increase in LC3-II levels in the presence of a lysosomal inhibitor (like Bafilomycin A1) indicates increased autophagic flux, whereas an increase without inhibition suggests a blockade in the pathway [24] [25].

- Immunofluorescence: Alternatively, visualize GFP-LC3 puncta (representing autophagosomes) under a confocal microscope. An increase in puncta number indicates autophagy induction or blockade of downstream steps.

Protocol 3: Evaluating Protein Aggregation via Filter Trap Assay

- Sample Preparation: Prepare solubilized protein extracts from brain tissue or cultured cells using buffers with mild detergents.

- Filtration: Dilute samples and filter through a cellulose acetate membrane under vacuum. Soluble proteins pass through, while large, insoluble aggregates are trapped.

- Immunodetection: Probe the membrane with an antibody specific to the protein of interest (e.g., anti-α-synuclein for PD, anti-polyglutamine for HD).

- Analysis: Detect the signal using chemiluminescence. The amount of trapped aggregate correlates with the signal intensity [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Protein Clearance Pathways

| Reagent / Assay | Function / Application | Example Use in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Proteasome Substrates (e.g., Suc-LLVY-AMC) | Quantifying chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity in cell lysates or purified complexes. | Measuring proteasome dysfunction in cerebral ischemia models [23] [22]. |

| LC3B Antibody | Detecting LC3-I to LC3-II conversion via Western blot or immunofluorescence to monitor autophagosome formation. | Assessing autophagic flux in neurons under oxidative stress [24]. |

| p62/SQSTM1 Antibody | Detecting p62, an autophagy receptor that is degraded along with its cargo; accumulation indicates autophagy impairment. | Demonstrating blocked autophagic degradation in disease models [24] [11]. |

| Lysosomal Trackers & pHrodo Dyes | Staining acidic organelles (lysosomes, autolysosomes) and tracking endocytosis based on vesicle acidification. | Studying lysosomal function and vesicle trafficking in live cells [24]. |

| PROTAC Molecules (Heterobifunctional degraders) | Inducing targeted degradation of specific proteins of interest (POIs) via the UPS for therapeutic exploration. | Degrading pathological tau or mutant huntingtin in preclinical studies [24] [25]. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | V-ATPase inhibitor that blocks autophagosome-lysosome fusion and lysosomal acidification. | Used to inhibit autophagic degradation and measure autophagic flux [24]. |

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

Therapeutic strategies aimed at enhancing protein clearance are a major focus of neurodegenerative disease research. These include:

UPS-Targeted Therapies: Small molecule proteasome activators are being explored to boost the degradation of misfolded proteins. Additionally, targeted protein degradation (TPD) technologies, such as PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs), are being developed to artificially recruit specific disease-causing proteins to E3 ubiquitin ligases for ubiquitination and degradation [25]. For example, PROTACs have been designed to target the androgen receptor and estrogen receptor in cancer, and this approach is now being applied to neurodegenerative disease targets [25].

ALP-Targeted Therapies: Pharmacological inducers of autophagy, such as Trehalose and Rapamycin analogs (e.g., Everolimus), have shown promise in preclinical models by enhancing the clearance of aggregate-prone proteins and improving neuronal survival [23] [11]. Trehalose has been shown to inhibit cerebral ischemia-induced protein aggregation by preserving proteasome activity [23] [10].

Lysosome-Targeting Therapies: For extracellular proteins and cell-surface receptors, LYsosome-TArgeting Chimeras (LYTACs) represent a novel modality that binds to both the extracellular protein and a lysosome-targeting receptor, shuttling the target for lysosomal degradation [24] [25].

Multi-Target Approaches: Given the crosstalk between pathways, interventions that simultaneously enhance both UPS and ALP function, such as activating the transcription factor TFEB (a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy), are under intense investigation [11].

Molecular chaperones, particularly heat shock proteins (HSPs), constitute a primary cellular defense mechanism against proteotoxic stress by ensuring proper protein folding, preventing aberrant aggregation, and facilitating the degradation of irreversibly damaged proteins. Within the context of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and Huntington's disease (HD), the collapse of this chaperone system contributes directly to the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates, a hallmark of these disorders. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of chaperone classification, structure, and mechanistic functions in protein homeostasis. It further examines the consequences of chaperone network failure in neurodegeneration and details contemporary experimental methodologies for investigating chaperone-client interactions. Finally, we synthesize current therapeutic strategies aimed at augmenting chaperone function to combat protein misfolding diseases, presenting quantitative data on drug development pipelines and reagent solutions for research professionals.

Cellular protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, represents a delicate equilibrium between protein synthesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation [27]. This balance is maintained by a sophisticated network of molecular chaperones, folding enzymes, and degradation machineries. Molecular chaperones, a class of highly conserved proteins, are fundamental components of this proteostasis network (PN) [28]. They function as cellular defense proteins by interacting with, stabilizing, and assisting other proteins in acquiring their functionally active native conformations, thereby preventing misfolding and aggregation [28] [29]. The term "heat shock protein" originates from their initial discovery in Drosophila as proteins markedly upregulated in response to thermal stress [27] [28]. However, their expression and function are critical under physiological conditions for managing nascent polypeptide chains and under various proteotoxic stresses, including oxidative stress and metabolic alterations [30] [29].

The challenge of maintaining proteostasis is particularly acute in neurons. As post-mitotic cells, neurons cannot dilute accumulated toxic aggregates through cell division, making them exceptionally vulnerable to proteostasis imbalances over time [29]. A hallmark of numerous neurodegenerative diseases is the intra- or extracellular accumulation of misfolded proteins that aggregate into toxic oligomers and insoluble fibrils, leading to synaptic dysfunction, activation of stress pathways, and ultimately neuronal death [10] [31] [11]. Key aggregating proteins include amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau in Alzheimer's disease, α-synuclein in Parkinson's disease, and huntingtin with expanded polyglutamine tracts in Huntington's disease [10] [12]. Molecular chaperones are deployed at every stage to combat this pathogenic cascade, from initial folding assistance to refolding, sequestration, and ultimate degradation of misfolded species [31] [29]. The failure of these defense mechanisms is a pivotal event in the progression of neurodegeneration, positioning chaperones as central players in both disease pathogenesis and potential therapeutic strategies [10] [28] [11].

Classification, Structure, and Mechanism of Molecular Chaperones

Molecular chaperones are systematically classified based on their molecular weight, structure, and mechanism of action. The major families include HSP100, HSP90, HSP70, HSP60, HSP40, and small HSPs (sHSPs), alongside regulatory co-chaperones that fine-tune their activity [28] [29].

Table 1: Major Molecular Chaperone Families and Their Characteristics

| Chaperone Family | Key Members | ATP-Dependent | Cellular Localization | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small HSPs (sHSPs) | HSPB1 (HSP27), HSPB5 | No | Cytosol, Nucleus | First line of defense; prevent aggregation by binding unfolding clients [28] |

| HSP40 (DnaJ) | DnaJA, DnaJB, DnaJC | Co-chaperone | Cytosol, Nucleus | Regulate HSP70 ATPase activity; client protein recruitment [28] |

| HSP70 | Hsp70, Hsc70 | Yes | Cytosol, Nucleus, ER, Mitochondria | Nascent chain folding; prevent aggregation; refold misfolded proteins; client delivery to degradative pathways [32] [29] |

| HSP90 | Hsp90α, Hsp90β, GRP94, TRAP-1 | Yes | Cytosol, ER, Mitochondria | Maturation of specific client proteins (e.g., kinases, transcription factors) [28] |

| HSP60/HSP10 | Chaperonins | Yes | Mitochondria, Cytosol | Facilitate folding in sequestered chambers, especially for complex proteins [28] |

Structural Insights and the Chaperone Cycle

Structural biology has profoundly advanced our understanding of chaperone mechanisms. The first crystal structures of HSP family members, including HSC70 (1993) and the N-terminal domain of HSP90 (1997), paved the way for elucidating their functional cycles [28]. Recent breakthroughs include resolving structures of ternary and quaternary complexes, such as the HSP90-CDC37-kinase and HSP90-HSP70-HOP-GR complexes, revealing the intricate mechanics of client protein regulation [28].

The HSP70 cycle serves as a paradigm for ATP-dependent chaperone function. HSP70 comprises an N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and a C-terminal substrate-binding domain (SBD). In the ATP-bound state, the SBD is open, allowing for rapid binding and release of client proteins with exposed hydrophobic regions. HSP40 co-chaperones, which themselves can bind clients, stimulate ATP hydrolysis by HSP70. This hydrolysis traps the client in the SBD. Subsequent nucleotide exchange, often facilitated by co-chaperones like HSP110, promotes ADP release and ATP rebinding, leading to client release. This cycle allows HSP70 to bind unfolded polypeptides, prevent aggregation, and facilitate folding [28] [32] [29].

The following diagram illustrates the core ATP-dependent cycle of HSP70 chaperones:

Similary, the HSP90 chaperone machinery involves a complex and dynamic process. HSP90 functions as a flexible dimer, and its cycle is regulated by a suite of co-chaperones like CDC37, p23, and Aha1. The cycle progresses through distinct conformational states (open, closed) that are coupled to ATP binding and hydrolysis. Co-chaperones act as molecular switches that dictate client recruitment, activation, or degradation. For instance, the co-chaperone CDC37 specifically recruits kinase clients to HSP90, forming a transient ternary complex that is essential for kinase stability and maturation [28].

Chaperone Functions in Neurodegeneration: Mechanisms and Consequences

In neurodegenerative proteinopathies, molecular chaperones engage in a multi-layered defense strategy against proteotoxic stress, targeting the misfolded proteins associated with these diseases.

Anti-Aggregation and Refolding

The primary function of chaperones is to bind to hydrophobic patches exposed on misfolded proteins, shielding them from inappropriate interactions that lead to aggregation. sHSPs like HSP27 act as a first line of defense by forming large oligomers that bind unfolding clients, preventing aggregation in an ATP-independent manner [28]. ATP-dependent chaperones like HSP70 and HSP40 then attempt to refold these stabilized clients. If initial refolding fails, the Hsp70-Hsp40 system, sometimes with the assistance of Hsp110 in metazoans, can function as a disaggregase, actively disentangling and solubilizing pre-formed aggregates to generate refoldable species [29].

Clearance of Misfolded Proteins

When refolding attempts are unsuccessful, chaperones pivot to facilitate the degradation of terminally misfolded proteins by partnering with cellular clearance machinery.

- Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS): Hsp70 can recognize misfolded clients and present them to E3 ubiquitin ligases, which tag the clients for processive degradation by the 26S proteasome [29].

- Autophagy-Lysosome Pathways: Chaperones are integral to multiple forms of autophagy.

- Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy (CMA): Hsc70 (a constitutive HSP70 isoform) recognizes proteins bearing a KFERQ-like motif and directs them to the lysosomal membrane receptor LAMP2A for translocation into the lysosome and degradation [31] [29].

- Macroautophagy: Misfolded proteins and aggregates that are too large for the proteasome or CMA are tagged by chaperones and selectively engulfed by autophagosomes via adaptor proteins like p62/SQSTM1. The autophagosome then fuses with the lysosome for bulk degradation [11] [29].

The following pathway diagram synthesizes the major chaperone-mediated defense mechanisms against proteotoxic stress:

Chaperone Dysfunction in Disease

Aging and chronic proteotoxic stress can lead to a state of "proteostatic collapse," where chaperone networks become overwhelmed and dysfunctional [30]. In many neurodegenerative diseases, components of the chaperone system are found sequestered within insoluble protein aggregates, rendering them inactive and further exacerbating the proteostasis imbalance [31] [32]. For example, in Parkinson's disease, α-synuclein can inhibit CMA by binding to LAMP2A, thereby blocking its own degradation and creating a vicious cycle of accumulation [31]. Similarly, in Alzheimer's and Huntington's disease, a specific subset of chaperones linked to protein synthesis (CLIPs) is repressed, weakening the cell's ability to manage newly synthesized proteins and existing misfolded species [10].

Experimental Methodologies for Chaperone Research