Optimizing Protein Homogeneity and Dispersity: A Comprehensive Guide for Reproducible Research and Drug Development

Achieving optimal protein homogeneity and dispersity is a critical, yet often challenging, prerequisite for reproducible research in biochemistry, structural biology, and drug development.

Optimizing Protein Homogeneity and Dispersity: A Comprehensive Guide for Reproducible Research and Drug Development

Abstract

Achieving optimal protein homogeneity and dispersity is a critical, yet often challenging, prerequisite for reproducible research in biochemistry, structural biology, and drug development. This article provides a comprehensive framework for scientists, covering the fundamental importance of sample quality for data integrity and the severe costs of irreproducibility. We explore a suite of methodological approaches, including high-pressure homogenization and enzymatic treatment, to refunctionalize protein aggregates and improve dispersity. A strong emphasis is placed on practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for challenging samples, followed by a comparative analysis of modern validation techniques like Mass Photometry and SEC-MALS. By integrating foundational knowledge with advanced application and validation protocols, this guide aims to empower researchers to standardize protein quality control, thereby enhancing the reliability and impact of their scientific outcomes.

Why Protein Homogeneity is Non-Negotiable: The Foundation of Reproducible Science

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between protein purity and protein homogeneity? Protein purity refers to the absence of contaminating proteins or other macromolecules in your sample, typically assessed by techniques like SDS-PAGE. Homogeneity (or dispersity) refers to the structural uniformity and oligomeric state distribution of your protein population—whether the molecules exist as consistent monomers, dimers, or higher-order assemblies without undesirable aggregates. A protein sample can be highly pure (free of contaminants) but heterogeneous in its oligomeric states, which can dramatically affect functional studies and experimental reproducibility [1].

Q2: Why does my purified protein show multiple peaks in size exclusion chromatography? Multiple peaks in SEC indicate a heterogeneous mixture of different molecular sizes in your sample. This could result from:

- Presence of aggregates (high molecular weight)

- Protein degradation or proteolysis (low molecular weight)

- Formation of incorrect oligomeric states

- Instability in the buffer or detergent conditions [2] Troubleshoot by analyzing peak fractions with SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry to identify the species present, then optimize purification and storage conditions.

Q3: What polydispersity index (PdI) value indicates an acceptably homogeneous sample? A polydispersity index value below 0.3 is generally considered acceptable and indicates a monodisperse, homogeneous system. Values approaching 1.0 indicate a highly heterogeneous mixture of particle sizes [3]. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) instruments provide this measurement, with lower PdI values representing more uniform protein preparations.

Q4: How can I stabilize a purified protein that tends to aggregate? Consider adding small molecule additives to your storage buffer:

- Amino acids (e.g., L-arginine, glycine)

- Sugars (e.g., sucrose)

- Osmolytes (e.g., glycerol) [4] Systematically screen these additives while monitoring homogeneity using size exclusion chromatography or dynamic light scattering.

Q5: My membrane protein aggregates after purification—what should I do? Membrane proteins require specific detergents to remain stable outside their native lipid environment. Implement a systematic detergent screen that tests different:

- Detergent types (varying head groups and alkyl chains)

- Salt concentrations

- pH conditions [2] Monitor results with analytical size exclusion chromatography (ASEC) to identify conditions that maintain mono-dispersity.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Homogeneity After Affinity Chromatography

Symptoms: Multiple peaks in SEC, high PdI in DLS measurements, inconsistent results in functional assays.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Protein aggregation | DLS, SEC-MALS | Add stabilizing additives (e.g., arginine, glycerol) [4], optimize buffer pH/salt [2] |

| Improper oligomeric state | Analytical SEC, Native PAGE | Screen different buffer conditions; consider ion strength effects [2] |

| Proteolytic degradation | SDS-PAGE, Mass spectrometry | Add protease inhibitors during purification; shorten purification time [5] |

| Detergent incompatibility | Analytical SEC, DLS | Perform detergent screen; evaluate mixed micelles [2] |

Protocol: Detergent Screening for Membrane Protein Homogeneity

- Purify membrane protein using standard affinity chromatography

- Prepare 10-15 different detergents at critical micelle concentration (CMC) in compatible buffers

- Exchange detergent by incubating purified protein with each detergent condition

- Analyze each condition using analytical size exclusion chromatography

- Select conditions producing single, symmetric peaks indicating mono-dispersity [2]

Problem: Low Protein Solubility and Recovery

Symptoms: Protein precipitation, low concentration after purification, high light scattering signal.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low intrinsic solubility | UV spectrophotometry, BCA assay | Add solubility enhancers (e.g., CHAPS, mild denaturants) [4] |

| Incorrect buffer conditions | pH measurement, conductivity | Screen pH (6-8) and salt concentration (50-250 mM) [4] |

| Oxidation or misfolding | Mass spectrometry, activity assays | Add reducing agents; optimize refolding conditions |

| Concentration too high | DLS, visual inspection | Dilute sample; use lower concentration for storage |

Protocol: High-Throughput Solubility Screening

- Prepare protein sample at consistent concentration

- Dispense into 96-well plate containing different buffer additives

- Incubate under standardized conditions (temperature, time)

- Measure solubility using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay or UV spectrophotometry [6]

- Confirm homogeneity of best conditions with DLS [3]

Quantitative Data Reference Tables

Acceptable Ranges for Homogeneity Assessment

Table 1: Key metrics for evaluating protein sample homogeneity

| Parameter | Acceptable Range | Ideal Value | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polydispersity Index (PdI) | < 0.3 | < 0.1 | Dynamic Light Scattering [3] |

| SEC Peak Symmetry | 0.8 - 1.2 | 0.9 - 1.1 | Analytical Size Exclusion Chromatography [2] |

| Mass Accuracy | ± 50 Da | ± 10 Da | Mass Spectrometry [1] |

| Purity Level | > 90% | > 95% | SDS-PAGE/Capillary Electrophoresis [1] |

Small Molecule Additives for Stability Enhancement

Table 2: Common additives to improve protein homogeneity and stability

| Additive | Concentration Range | Mechanism of Action | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Arginine | 50 - 500 mM | Suppresses aggregation; enhances solubility [4] | May affect binding assays |

| Glycerol | 5 - 20% (v/v) | Prevents denaturation; reduces surface adsorption [4] | High viscosity can affect some assays |

| Sucrose | 0.2 - 1.0 M | Excluded volume effect; stabilizes native state [4] | Can increase solution osmolarity |

| Glycine | 50 - 200 mM | Improves solubility; crystallization enhancer [4] | pH-dependent effects |

| Reducing Agents | 1 - 10 mM | Prevents disulfide aggregation | Incompatible with some enzymes |

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Basic Protocol: Assessing Protein Homogeneity

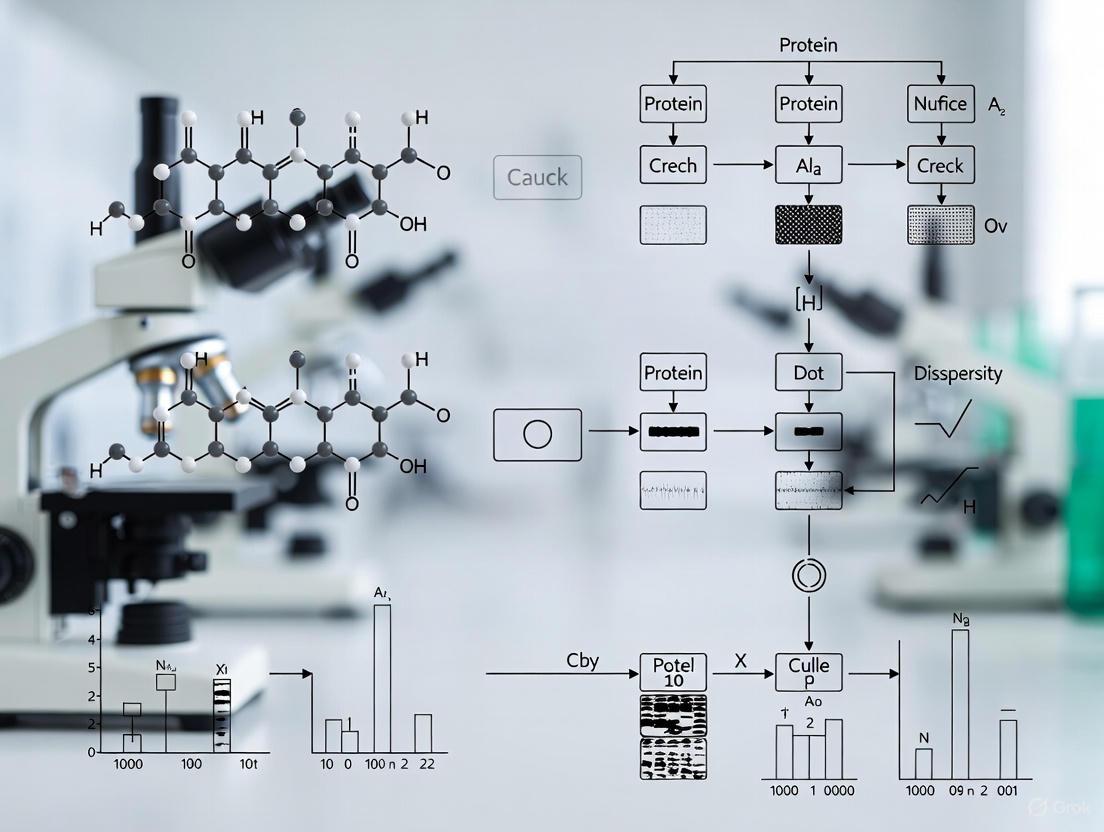

Homogeneity Assessment Workflow

Comprehensive Approach: Systematic Membrane Protein Optimization

Membrane Protein Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents for optimizing protein homogeneity and dispersity

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Homogeneity Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Detergents | DDM, OG, LDAO, Fos-Choline | Solubilize membrane proteins; maintain native state [2] |

| Chromatography Resins | Ni-NTA, Glutathione, Antibody-conjugated | Affinity purification with specific binding [5] |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, Complete Mini Tablets | Prevent proteolytic degradation during purification [5] |

| Stabilizing Additives | Arginine, glycerol, sucrose | Enhance solubility; prevent aggregation [4] |

| Analysis Standards | Molecular weight markers, SEC standards | Calibrate instruments; validate separation performance |

Implementation Notes:

- Detergent selection is empirical and protein-specific; systematic screening is essential [2]

- Additive effectiveness varies by protein; implement matrix screening approaches

- Quality control should be performed at each purification step, not just the final product [1]

- Document all conditions including buffer composition, temperature, and protein concentration for reproducibility [1]

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Why is my protein yield low after purification?

Low yield can result from protein degradation, inefficient elution, or protein loss during handling.

- Protein Degradation: Perform all purification steps at 4°C and include protease inhibitors during cell lysis to minimize degradation [7].

- Inefficient Elution: For affinity purification, ensure elution conditions are sufficient. If protein doesn't elute, try using more stringent conditions such as increasing NaCl concentration to 2M or decreasing pH. Alternatively, strip the column with 1mM DTT or 10-100mM EDTA [7].

- Handling Loss: Avoid techniques that cause shear stress, such as vigorous pipetting, vortexing, or high-speed centrifugation. Use wide-bore pipette tips and minimize mechanical agitation [8].

How can I reduce protein aggregation in my samples?

Aggregation often stems from improper buffer conditions, oxidation, or stress during purification.

- Buffer Conditions: Optimize pH and salt concentration to keep the protein stable. Sudden pH changes should be avoided. Include additives like glycerol to prevent aggregation [8].

- Prevent Oxidation: To protect sensitive cysteine residues from forming unwanted disulfide bonds, include reducing agents like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol in your buffers. For highly sensitive proteins, consider performing purification steps under an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon) [8].

- Control Hydrolysis: In enzymatic processes, controlled hydrolysis can break down complex protein structures into smaller, more functional fragments and improve solubility [9].

What can I do if my His-tagged protein doesn't bind to the Ni-NTA resin?

Several factors can prevent binding of His-tagged proteins to immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) resins.

- His-Tag is Inaccessible: If the tag is hidden due to protein folding, try a denaturing elution to expose it [7].

- Stringent Conditions: The presence of imidazole in the binding buffer can interfere. Use a lower concentration (10mM or less). Also, reduce the NaCl concentration from 500mM to 250mM or less [7].

- Resin Integrity: Ensure the resin has not frozen or been stripped by strong chelating agents. Frozen resin that forms clumps is likely non-functional [7].

How can I improve the solubility and dispersity of my purified protein?

Improving solubility is key to achieving homogeneous protein samples.

- Buffer Additives: Add detergents like 0.1% Triton X-100 or Tween-20 to help solubilize proteins. For stubborn proteins, include up to 0.2% Sarkosyl in a guanidine lysis buffer [7].

- Enzymatic Treatment: Using proteases or transglutaminases can strategically modify protein structures. This enzymatic treatment enhances solubility, improves digestibility, and creates a smoother texture (mouthfeel) by breaking proteins into smaller fragments [9].

- Clarify Samples: Before chromatography, always filter and clarify the lysate using centrifugation and 0.45µm or 0.22µm membrane filters to remove debris that can promote aggregation [8].

Table 1: Common Buffer Additives to Enhance Protein Solubility and Stability

| Additive | Typical Concentration | Primary Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerol | 5-20% | Reduces aggregation, stabilizes structure | Alters osmotic pressure; may interfere with assays |

| DTT / β-Mercaptoethanol | 1-20 mM | Prevents oxidation of cysteine residues | Unstable in buffer; prepare fresh |

| CHAPS | 0.1-2% | Detergent; solubilizes membrane proteins | Can interfere with ion exchange chromatography |

| Imidazole | 1-20 mM | Competes for resin binding in His-tag purifications | Use low concentrations in binding/wash steps |

| NaCl | 50-500 mM | Controls stringency; reduces non-specific binding | High concentrations can cause salting out |

| Protease Inhibitors | As recommended | Prevents proteolytic degradation | Cocktails often most effective |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Protein Purification Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Yield | Protein degradation, inefficient elution | Use protease inhibitors; optimize elution buffer pH/stringency [7] [8] | Maintain cold chain; include reducing agents |

| Poor Binding | Tag inaccessibility, harsh conditions | Try denaturing conditions; reduce imidazole/NaCl [7] | Check protein sequence; optimize binding buffer |

| Protein Aggregation | Oxidation, buffer mismatch | Add reducing agents, optimize pH/salt [8] | Screen buffer conditions; use stabilizing additives |

| Non-specific Binding | Insufficient washing | Increase wash stringency with NaCl/imidazole [7] | Optimize wash buffers; include mild detergents |

| Low Solubility | Hydrophobic regions exposed | Use chaotropes, detergents, enzymatic treatment [9] [7] | Use solubility enhancers like glycerol |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Enzymatic Treatment to Enhance Protein Solubility and Functionality

This protocol uses enzymatic hydrolysis to modify protein isolates, improving their solubility, digestibility, and sensory characteristics for research and development applications [9].

Materials

- Protein Isolate (e.g., Whey, Soy, or Pea Protein Isolate)

- Proteolytic Enzymes (e.g., specific proteases)

- Reaction Buffer (pH and composition suitable for the enzyme)

- Water Bath or incubator for temperature control

- pH Meter

- Equipment to stop reaction (e.g., heat source for inactivation)

Method

- Preparation: Dissolve the protein isolate in the reaction buffer to a desired concentration.

- Hydrolysis: Add the selected proteolytic enzyme to the protein solution. The enzyme-to-substrate ratio should be determined empirically.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture at the optimal temperature and pH for the enzyme. Continuously monitor and control parameters like temperature, pH, enzyme concentration, and reaction time [9].

- Reaction Termination: After the desired degree of hydrolysis is achieved, inactivate the enzyme (e.g., by heat treatment).

- Recovery: The resulting hydrolysate can be further processed, dried, and analyzed for improved properties.

Key Parameters for Optimization

- Degree of Hydrolysis: Control the reaction time to achieve the optimal balance between improved functionality and potential bitterness.

- Enzyme Specificity: Choose enzymes that target specific peptide bonds to achieve the desired protein profile.

- Reaction Conditions: Maintain precise control over temperature and pH throughout the process to ensure reproducible results.

Protocol: Affinity Purification of His-Tagged Proteins Under Native Conditions

This protocol outlines the steps for purifying soluble, correctly folded His-tagged proteins using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography [7].

Materials

- Ni-NTA Resin

- Lysis Buffer: (e.g., 50 mM NaH₂PO₄, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0)

- Wash Buffer: (e.g., 50 mM NaH₂PO₄, 300 mM NaCl, 20-50 mM imidazole, pH 8.0)

- Elution Buffer: (e.g., 50 mM NaH₂PO₄, 300 mM NaCl, 250-500 mM imidazole, pH 8.0)

- Protease Inhibitor Cocktail

- Lysozyme (optional)

- DNase I (optional)

- Centrifuge and Tubes

- Chromatography Column

Method

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend cell pellet in Lysis Buffer. Lyse cells by sonication, homogenization, or with lysozyme. Include protease inhibitors to prevent degradation. For viscous lysates, add DNase I and incubate on ice.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at >10,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble debris. Filter the supernatant through a 0.45μm filter.

- Binding: Incub the clarified lysate with pre-equilibrated Ni-NTA resin for 30-60 minutes at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Washing: Wash the resin with 10-20 column volumes of Wash Buffer. If non-specific binding is high, increase the imidazole concentration or add 0.1% Triton X-100 [7].

- Elution: Elute the bound protein with Elution Buffer. Use a step gradient of imidazole (e.g., 100, 250, 500 mM) or a linear gradient for better separation.

- Analysis: Analyze fractions by SDS-PAGE. Pool fractions containing the target protein and dialyze into an appropriate storage buffer.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Optimizing Protein Homogeneity

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ni-NTA Resin | Affinity purification of His-tagged proteins | Avoid freezing; can be stripped and recharged if contaminated [7] |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevent proteolytic degradation during purification | Essential for maintaining protein integrity; use broad-spectrum for unknown proteases [7] [8] |

| Proteolytic Enzymes | Modify protein structure to enhance solubility & functionality | Select based on specificity; control reaction time to achieve desired hydrolysis [9] |

| DTT / β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents to prevent disulfide bond formation | Critical for cysteine-rich proteins; prepare fresh solutions [7] [8] |

| Detergents (Triton X-100, Tween-20) | Reduce non-specific binding, improve solubility | Use at 0.1% in wash buffers; choose based on downstream applications [7] |

| Imidazole | Competitor for His-tag binding sites | Use low concentrations (10-20mM) in binding/wash buffers; higher (250-500mM) for elution [7] |

| Chromatography Columns | Housing for purification resins | Choose appropriate size; avoid exceeding pressure limits (~2.8 psi for Ni-NTA) [7] |

FAQ: Understanding and Preventing Aggregation in Pea Protein

What causes pea protein to aggregate in my experiments? Pea protein aggregation is primarily driven by hydrophobic interactions and disulfide bonding [10]. During processing or experimental treatments like heating or enzymatic hydrolysis, the native structure of the protein is disrupted. This exposes buried hydrophobic amino acid residues, which then interact with each other to form insoluble aggregates [10]. Additionally, cross-linking enzymes such as transglutaminase can catalyze covalent bonds between protein molecules, creating a stable protein network that is difficult to disperse [10].

How can I improve the solubility and dispersibility of a commercial pea protein isolate? Employing sustainable non-thermal processing techniques is an effective strategy. Research indicates that enzymatic treatment significantly enhances solubility, with studies showing improvements from 64.28% to 66.55% [11]. Furthermore, adding small, affordable molecules to your buffer conditions can improve protein stability and homogeneity. Common additives include L-arginine (0.2 - 0.5 M) to increase solubility, and sucrose (0.2 - 1.0 M) or glycerol (5-20%) as stabilizers that help maintain the native protein fold [4].

My sample is viscous and doesn't run well on SDS-PAGE. What should I do? Viscosity is often caused by contaminating genomic DNA [12]. This can be remedied by shearing the DNA through sonication or by passing the lysate through a narrow-gauge needle [12] [13]. Furthermore, ensure your sample is properly denatured. Increasing the boiling time (a common practice is 5 minutes at 98°C) with fresh reducing agents like DTT can help linearize the proteins for better separation [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Scenarios and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Protein Solubility | Hydrophobic aggregation from processing; unsuitable buffer conditions. | Use non-thermal pre-treatments (e.g., ultrasonication); modify buffer with small molecules like L-arginine (0.2-0.5 M) or glycerol (5-20%) [11] [4]. |

| High Sample Viscosity | Contamination by genomic DNA. | Shear genomic DNA via sonication or pass lysate through a 28-gauge needle [12] [13]. |

| Poor Band Separation on SDS-PAGE | Protein overload; improper denaturation; high salt content. | Load less protein (validate optimal amount); ensure fresh DTT and proper boiling (5 min at 98°C); reduce salt concentration via dialysis or desalting columns [12] [14]. |

| Protein Degradation | Activity of endogenous proteases in the lysate. | Perform lysis on ice and include a cocktail of protease inhibitors (e.g., PMSF, Leupeptin, Aprotinin) in the lysis buffer [13]. |

Quantitative Data: Efficacy of Non-Thermal Processing Techniques

The following table summarizes data on non-thermal methods for improving pea protein functionality, as reported in recent scientific literature [11].

| Processing Technique | Key Outcome Metric | Result / Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasonication | Protein Content (Yield) | Increased yield from 82.76% to 85.76% [11] |

| Enzymatic Treatment | Protein Digestibility | Enhanced by 20.86% to 22.50% [11] |

| Enzymatic Treatment | Protein Solubility | Improved from 64.28% to 66.55% [11] |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing and Mitigating Aggregation

Protocol 1: Solubility and Homogeneity Check via Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

- Objective: To determine the size distribution and polydispersity of pea protein particles in solution, identifying the presence of large aggregates [15].

- Materials: Purified pea protein sample, DLS instrument, appropriate buffer (e.g., Tris or HEPES, pH 6-8).

- Steps:

- Clarify the protein sample by centrifugation at >10,000 x g for 10 minutes.

- Dilute the supernatant to a concentration within the optimal range for your DLS instrument (typically 0.1-1 mg/mL).

- Load the sample into a cuvette and place it in the instrument.

- Measure the hydrodynamic radius and polydispersity index (PDI). A PDI value below 0.2 is generally considered monodisperse.

Protocol 2: Improving Solubility via Enzymatic Modification

- Objective: To hydrolyze pea protein, thereby breaking it into smaller, more soluble peptides and reducing hydrophobic aggregation [11] [10].

- Materials: Commercial pea protein isolate, suitable protease (e.g., Alcalase), buffer, water bath.

- Steps:

- Prepare a dispersion of pea protein (e.g., 2-5% w/v) in a suitable buffer for the enzyme.

- Heat the dispersion to the optimal temperature for the selected protease.

- Add the enzyme at the recommended enzyme-to-substrate ratio.

- Incubate for a predetermined time while stirring.

- Inactivate the enzyme by heating (e.g., 85°C for 5-10 minutes).

- Centrifuge to remove any remaining insoluble aggregates and collect the soluble fraction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| L-Arginine | An amino acid additive that effectively improves protein solubility and stability in solution, often used in concentrations of 0.2-0.5 M [4]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | A cocktail (e.g., PMSF, Leupeptin) added to lysis buffers to prevent protein degradation by endogenous proteases released during cell breakage [13]. |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) | A reducing agent that breaks disulfide bonds, a key force in protein aggregation. It is used in sample buffers for SDS-PAGE to ensure complete denaturation [14] [13]. |

| CHAPS Detergent | A zwitterionic detergent effective at solubilizing membrane proteins and preventing aggregation of hydrophobic proteins, which can remain insoluble in milder detergents like Triton X-100 [13]. |

Workflow Visualization

This diagram illustrates the decision-making process for diagnosing and resolving common pea protein aggregation issues in a research setting.

Establishing Minimal Quality Control (QC) Standards for Every Protein Reagent

In the realm of biological research and drug development, purified proteins are fundamental reagents. However, inadequate quality of these proteins is a significant contributor to poor data reproducibility, costing the research community billions annually and impeding scientific progress [16]. Establishing and adhering to minimal quality control (QC) standards is not merely a best practice but an essential requirement for generating reliable, reproducible, and interpretable experimental data. This guide provides a foundational framework and practical troubleshooting advice to ensure your protein reagents meet the rigorous standards required for high-quality research.

The Core Minimal QC Standards Framework

A consensus among protein science experts, as outlined by networks like ARBRE-MOBIEU and P4EU, defines three pillars of minimal QC: essential information to document, mandatory quality control tests, and extended characterizations for specific applications [16].

Minimal Information to Document

For any protein reagent used in a study, the following information must be recorded and available:

- Complete Construct Sequence: For recombinant proteins, the full sequence of the expressed construct must be provided, ideally verified by DNA sequencing after cloning [16].

- Detailed Protocols: Expression, purification, and storage conditions should be exhaustively described to enable precise reproduction in any laboratory [16].

- Concentration Measurement: The specific method used for determining protein concentration (e.g., Bradford, BCA, UV absorbance) must be stated [16].

Minimal QC Tests to Perform

These three tests form the non-negotiable core of protein QC, utilizing widely available techniques.

- Purity and Integrity: Assessed by techniques like SDS-PAGE, Capillary Electrophoresis (CE), or Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC). Mass Spectrometry (MS) is highly recommended for detecting contaminating proteins, proteolysis, and minor truncations [16].

- Homogeneity and Dispersity: This refers to the size distribution and oligomeric state of the protein sample. The presence of incorrect oligomeric states or aggregates can severely skew results like enzyme kinetics. This is best evaluated by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), or preferably, SEC coupled to multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) [16].

- Molecular Identity: Confirm you have the correct protein using Mass Spectrometry, either through "bottom-up" (mass fingerprinting of tryptic digests) or "top-down" (measuring the intact protein mass) approaches. This verifies the protein's identity and intactness [16].

Extended QC Tests

Depending on the downstream application, further characterization is crucial:

- Folding State: Using methods like circular dichroism.

- Specific Activity: Essential for enzymes.

- Endotoxin Levels: Must be checked for proteins used in cell culture experiments [16].

- Thermostability: Assessed via techniques like Thermofluor (Differential Scanning Fluorimetry) to identify optimal storage and assay conditions [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential QC Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Key reagents and materials for protein quality control.

| Item | Function in QC |

|---|---|

| SDS-PAGE Gels & Equipment | Separates proteins by molecular weight to assess purity, integrity, and detect proteolysis [18] [19]. |

| Mass Spectrometer | Confirms protein identity, intact mass, and detects post-translational modifications [16] [18]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | Measures hydrodynamic radius and assesses sample monodispersity vs. aggregation [18]. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) System | Separates protein species based on size and hydrodynamic volume to evaluate oligomeric state and homogeneity [16]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Measures protein concentration and detects common contaminants like nucleic acids [18]. |

| Affinity Resins & Columns | For initial purification of tagged recombinant proteins [20]. |

| Specific Activity Assay Components | Reagents and substrates needed to measure the functional output of enzymatic proteins. |

| Thermofluor-Compatible Dyes (e.g., SYPRO Orange) | Report on protein thermal unfolding and stability under different buffer conditions [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Protein QC

Q1: My protein is pure according to SDS-PAGE. Why do I need other QC tests? SDS-PAGE is an excellent first check, but it has limitations. It may not detect aggregates (which can remain in the well), minor proteolytic events that change the mass by only a few amino acids, or incorrectly folded protein that has the same molecular weight. DLS and Mass Spectrometry are essential complementary techniques that provide a deeper analysis of homogeneity and molecular identity [16] [18].

Q2: What does a "poly-disperse" DLS result mean, and is it always bad? A poly-disperse result indicates a mixture of particles of different sizes in your sample. This is not inherently bad but requires interpretation. It could signal the presence of undesirable aggregates or simply a defined oligomeric mixture of your protein (e.g., a dimer in equilibrium with a tetramer). While a monodisperse peak is often the goal, the critical question is whether the dispersity affects your protein's function in downstream applications. SEC or SEC-MALS can help further resolve the species present [16].

Q3: How can I quickly improve the stability and homogeneity of my protein?

Use a Thermofluor screen. This method allows you to rapidly test dozens of different buffer conditions (pH, salts, additives) in a 96-well plate format to identify those that maximize your protein's thermal stability (Tm). A higher Tm often correlates with improved homogeneity and better behavior in concentration, crystallization, and activity assays [17].

Troubleshooting Common Protein Purification and QC Issues

Table 2: Common problems and solutions in protein QC.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|

| No protein in final elution | Construct/expression issue. | Verify DNA sequence and that the tag is in-frame. Check expression via SDS-PAGE and western blot with an anti-tag antibody [20]. |

| Low yield or protein concentration | Protein instability or degradation. | Optimize lysis and purification buffers (see Thermofluor, Q3). Add protease inhibitors. Check for and remove degradation-prone regions by construct truncation [17] [19]. |

| High aggregate content | Unstable protein or harsh purification. | Optimize buffer pH and salt concentration. Include stabilizing additives (e.g., sugars, glycerol). Avoid excessive shear forces. Use a gentle elution method [20]. |

| Incorrect molecular weight by MS | Proteolysis or unexpected PTMs. | Check for truncated forms by SDS-PAGE. Use bottom-up MS to map sequence coverage and identify modifications. Verify purification protocol to minimize protease activity [18]. |

| Poor activity despite good purity | Protein misfolding or inactive aggregates. | Check folding state (e.g., by circular dichroism). Use SEC to separate and test activity of different oligomeric states. Ensure reducing environment for proteins with disulfide bonds [16]. |

Workflow Diagram for Protein QC

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for implementing a minimal QC standard for any protein reagent.

Integrating these minimal QC standards into your daily research practice is a critical step toward enhancing data reproducibility and reliability. The upfront investment in thorough characterization saves immeasurable time and resources that would otherwise be wasted on interpreting irreproducible results. By adopting this framework, the scientific community can collectively raise the standard of protein-based research, fostering greater confidence in published data and accelerating discovery.

Practical Strategies for Enhancing Dispersity: From Homogenization to Hybrid Systems

High-Pressure Homogenization (HPH) serves as a critical mechanical processing technology in pharmaceutical and biochemical research for optimizing protein homogeneity and dispersity in purified samples. By forcing protein suspensions through a narrow valve under extreme pressures, HPH utilizes a combination of cavitation, shear forces, and turbulence to disrupt insoluble protein aggregates—a common challenge in therapeutic protein development. This technology directly addresses the industry-wide need for efficient particle size reduction and structural modification of plant-based and recombinant proteins, ultimately enhancing their functional properties for drug formulations and delivery systems. The controlled application of HPH enables researchers to achieve reproducible results in sample preparation, significantly improving batch-to-batch consistency in protein-based therapeutic development.

Technical Mechanisms: How HPH Disrupts Protein Aggregates

Fundamental Disruption Forces

The aggregate disruption capability of HPH stems from intense mechanical forces generated as protein suspensions pass through the homogenizer's microscopic gap:

- Shear Stress: Laminar and turbulent flow profiles create strong velocity gradients that mechanically tear apart aggregate structures [21].

- Cavitation: Rapid pressure changes cause vapor bubble formation and implosion, generating shockwaves that fracture aggregate particles [22].

- Impact and Collision: High-velocity particles collide with each other and with homogenizer surfaces, causing further size reduction [22].

- Turbulence: Intense eddy currents in the fluid create chaotic flow patterns that exert twisting and tearing forces on aggregates [22].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential mechanisms of protein aggregate disruption as material passes through an HPH valve:

Structural Modifications in Proteins

HPH induces specific structural changes to protein molecules that enhance dispersity:

- Quaternary Structure Disassembly: HPH disrupts non-covalent bonds holding multi-subunit complexes together, effectively dissociating legumin hexamers and vicilin trimers in plant proteins [21].

- Tertiary Structure Unfolding: Mechanical forces partially unfold compact globular structures, exposing hydrophobic regions and functional groups [23].

- Aggregate Fragmentation: Large insoluble aggregates break into smaller, more uniform particles with increased surface area [10].

- Secondary Structure Modifications: Circular dichroism studies demonstrate alterations in α-helix and β-sheet content, affecting protein solubility and functionality [21].

Table 1: HPH-Induced Structural Changes and Functional Outcomes in Plant Proteins

| Protein Type | Structural Modification | Functional Outcome | Research Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pea Protein | Decreased vicilin-to-legumin ratio; partial unfolding | Increased solubility from 18% to 42%; improved emulsion stability | [21] |

| Hazelnut Protein | Reduced particle size; secondary structure changes | Enhanced gel hardness (1.52g to 2.06g); improved water holding capacity | [23] |

| Soy Protein | Disruption of insoluble aggregates; increased surface hydrophobicity | Improved gel formation; higher storage modulus (291Pa to 528Pa) | [23] |

| Lentil Protein | Structural unfolding; increased free sulfhydryl groups | Enhanced solubility, foaming and emulsifying capacity | [21] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common HPH Experimental Challenges

Pressure and Flow-Related Issues

Problem: Inability to reach or maintain target homogenization pressure during protein processing.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Homogenizing Valve Leakage: Worn valve seats or O-rings cause pressure loss and noisy operation. Inspect homogenizing head and seat for damage; replace worn O-rings and anti-extrusion rings [24] [25].

- Suction/Discharge Valve Malfunction: Broken springs, damaged balls, or worn valve seats prevent proper pumping action. Remove front covers to inspect valve components; replace broken springs and damaged valves [26].

- Plunger Seal Leakage: Worn plunger seals allow fluid bypass, reducing pressure generation. Check for leakage at plunger seals; replace if worn or damaged [25].

- Cavitation: Air entrapment in protein suspension creates vapor bubbles that disrupt flow. Degas protein solutions before processing; ensure proper feed pressure and check for suction line leaks [26].

Material Flow and Quality Issues

Problem: Reduced flow rate or inconsistent homogenization results with protein samples.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Main Motor Belt Slippage: Worn or loose belts reduce plunger speed and flow rate. Inspect drive belts for wear and proper tension; replace if necessary [24] [25].

- Partially Blocked Valves: Protein aggregates or crystals obstruct valve operation. Disassemble and clean valves; pre-filter concentrated protein solutions if needed [26].

- Incorrect Protein Concentration: Excessive viscosity hinders proper flow through the homogenizer. Optimize protein concentration (typically 1-10% w/v) for your specific sample [21] [23].

- Temperature Fluctuations: Protein viscosity changes with temperature, affecting flow characteristics. Use heat exchangers to maintain constant temperature (often 20-30°C) during processing [21].

Equipment Performance and Maintenance Issues

Problem: Unusual noises, motor overload, or gradual performance degradation.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Main Motor Overload: Excessive homogenization pressure or mechanical resistance strains the motor. Verify pressure settings are within manufacturer recommendations; check for worn power transmission components [24] [25].

- Worn Bearings or Connecting Rods: Mechanical damage causes unusual knocking noises. Inspect bearings, connecting rod nuts/bolts, and bushings for wear; replace damaged components [24].

- Pressure Gauge Malfunction: Faulty gauges provide inaccurate pressure readings. Check if pointer returns to zero after pressure release; replace if defective [24].

- General Wear and Tear: Regular operation with abrasive samples (e.g., calcium-fortified proteins) accelerates component wear. Implement preventive maintenance schedule; replace wear parts based on manufacturer recommendations [22] [25].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Common HPH Problems in Protein Processing

| Problem | Possible Causes | Immediate Actions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure instability | Cavitation, air in product, worn valves | Degas sample, check suction lines, inspect valves | Regular valve inspection, proper sample preparation |

| Reduced flow rate | Worn plunger seals, blocked valves, motor issues | Inspect seals and valves, check motor speed | Regular seal replacement, sample pre-filtration |

| Abnormal noise | Worn bearings, loose components, cavitation | Identify noise source, check bearings and connectors | Routine lubrication, proper equipment operation |

| Product temperature increase | Insufficient cooling, high pressure, frequent passes | Verify heat exchanger function, optimize pressure | Maintain cooling systems, limit recycle passes |

| Inconsistent results | Worn homogenizing valve, pressure fluctuations | Inspect homogenizing valve, verify pressure settings | Regular valve maintenance, pressure calibration |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

HPH Application and Optimization

Q1: What HPH pressure levels are most effective for different protein types?

- Plant proteins (pea, lentil): 60-100 MPa for 1-5 cycles significantly improves solubility and functionality [21].

- Nut proteins (hazelnut, almond): 100-150 MPa effectively reduces particle size and enhances gelation properties [23].

- General protein aggregate disruption: Start with 50-80 MPa and increase incrementally based on particle size analysis.

Q2: How does HPH compare to other protein disruption methods? HPH provides mechanical, non-thermal processing that avoids chemical modification. Compared to ultrasonication, HPH typically achieves more uniform particle size reduction. Unlike enzymatic treatment, HPH doesn't introduce foreign substances but may cause more extensive structural unfolding than mild enzymatic approaches [10].

Q3: What is the optimal number of passes for protein homogenization? Most studies utilize 1-5 passes, with diminishing returns beyond this range. For pea proteins, 5 cycles at 60 MPa significantly modified protein structure while minimizing excessive denaturation. Always validate passes for your specific protein through solubility and activity assays [21].

Technical Specifications and Limitations

Q4: What protein concentrations can be effectively processed with HPH? Typical working concentrations range from 1-10% (w/v). For research-scale protein isolation, 1% solutions are common [21]. Higher concentrations may require optimization of pressure and cycle number to avoid clogging and ensure efficient homogenization.

Q5: How does HPH affect protein stability and denaturation? HPH can cause partial denaturation through mechanical unfolding, which often enhances functional properties like solubility and emulsification. However, excessive pressure (>150 MPa) or cycles may cause undesirable aggregation. Always monitor thermal stability via DSC and structural changes via circular dichroism [21].

Q6: Can HPH process sensitive therapeutic proteins? Yes, with parameter optimization. The absence of heat and chemicals makes HPH suitable for sensitive proteins. Start with lower pressures (20-50 MPa) and minimal cycles, then gradually increase while monitoring biological activity retention.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard HPH Protocol for Plant Protein Modification

This methodology is adapted from published research on pea and hazelnut protein modification [21] [23]:

Materials and Reagents:

- Protein isolate (commercial or extracted via alkaline extraction/acid precipitation)

- Appropriate buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer saline, pH 7.0-7.5)

- High-pressure homogenizer with temperature control

- Ice bath for sample collection

- Analytical equipment (SDS-PAGE, dynamic light scattering, spectrophotometer)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare protein solution at 1% (w/v) concentration in appropriate buffer

- Stir for 2 hours at room temperature to ensure complete hydration

- Adjust pH to desired value (typically 7.0 for most applications)

- Pre-filter through coarse filter if large aggregates are visible

HPH Processing:

- Set homogenizer temperature control to maintain 20-30°C during processing

- Prime system with buffer to establish stable flow

- Load protein sample into feed reservoir

- Process through homogenizer at selected pressure (60-150 MPa)

- Subject to predetermined number of passes (typically 3-5 cycles)

- Collect samples after each pass for analysis if studying progressive effects

Post-Processing:

- Immediately cool processed samples on ice

- Analyze for particle size, solubility, and structural changes

- Store at appropriate conditions for further experimentation

Validation Measurements:

- Solubility: Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 10 min; measure protein in supernatant

- Particle Size: Dynamic light scattering to determine size distribution

- Structural Analysis: SDS-PAGE under reducing and non-reducing conditions

- Functional Properties: Emulsifying capacity, water/oil holding capacity as required

Research Reagent Solutions for HPH Protein Studies

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for HPH Protein Research

| Reagent/Equipment | Specifications | Research Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Isolates | Pea, hazelnut, soy; 85-90% purity | Primary substrate for HPH modification | Structural functionality studies [21] [23] |

| Buffer Systems | Phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.5-7.5) | Maintain pH during processing | Stability and solubility measurements [21] |

| Glucono-δ-lactone (GDL) | Food-grade acidulant | Induce acid-induced gelation | Cold-set gel formation studies [23] |

| SDS-PAGE Reagents | Precast gels, Coomassie Blue | Analyze protein composition and degradation | Monitor HPH-induced structural changes [21] |

| Dynamic Light Scattering | Particle size analyzer | Measure aggregate size distribution | Quantify HPH disruption efficiency |

Enzymatic Hydrolysis for Improved Solubility and Digestibility

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: My protein hydrolysate has an unacceptably bitter taste. What is the cause and how can I mitigate this?

- Cause: Bitterness is often caused by the formation of short-chain peptides with hydrophobic amino acids during hydrolysis [9].

- Solution: You can manage this by:

- Controlling the Degree of Hydrolysis (DH): Avoid over-hydrolysis, as extensive breakdown increases bitter peptide formation [9].

- Enzyme Selection: Use specific proteases like pepsin, which is known to produce hydrolysates with a low bitter taste [27].

- Post-Hydrolysis Treatment: Apply purification techniques such as ultrafiltration to remove small, bitter peptides [28].

FAQ: The solubility of my protein sample has not improved after enzymatic hydrolysis. What might have gone wrong?

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect Enzyme Selection: Different enzymes cleave proteins at different sites. Alkaline protease, for example, has been shown to significantly enhance solubility in mung bean protein isolates [29]. Ensure the enzyme you select is appropriate for your specific protein source.

- Suboptimal Reaction Conditions: Parameters like pH, temperature, and enzyme-to-substrate ratio (E/S) are critical. For instance, a study on yak whey protein found optimal hydrolysis with alkaline protease at pH 8.0 and 62°C [28]. Use experimental design methodologies like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to optimize these conditions for your protein.

- Inadequate Purity of Starting Material: Contaminants in your initial protein isolate can interfere with the hydrolysis reaction. Ensure your protein sample meets minimal quality control standards, including checks for purity and identity, before beginning hydrolysis [16].

FAQ: How can I ensure my purified protein or hydrolysate is of high quality and suitable for my research?

- Guidance: Implement the following minimal quality control (QC) tests as a standard practice [16]:

- Purity Analysis: Use SDS-PAGE, Capillary Electrophoresis (CE), or Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC) to detect contaminating proteins or sample proteolysis.

- Homogeneity/Dispersity Assessment: Analyze the oligomeric state and check for aggregates using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) or Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC). This is crucial for accurate concentration measurement and reproducible results in downstream experiments like enzyme kinetics.

- Identity Confirmation: Confirm the protein's identity and intactness using mass spectrometry (MS), either through mass fingerprinting of tryptic digests or by measuring the intact protein mass.

Summarized Experimental Data

The following tables consolidate key quantitative data from recent studies to guide your experimental planning.

Table 1: Optimal Hydrolysis Conditions for Different Protein Sources

| Protein Source | Optimal Enzyme | Optimal pH | Optimal Temperature (°C) | E/S Ratio | Hydrolysis Time (Hours) | Key Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soy Protein Isolate | Pepsin | 1.5-3.5 (Acidic) | Not Specified | 1.5% (w/w) | 4 | High protein recovery (89.70%) and bioactive peptides [27]. | |

| Yak Whey Protein Concentrate | Alkaline Protease | 8.0 | 62 | 7500 U/g | 2.5 | Highest peptide concentration (17.21 mg/mL) [28]. | |

| Mung Bean Protein Isolate | Alcalase | 8.5 | 55 | 5.88% (v/w) | 3.56 | ~33% Degree of Hydrolysis; improved solubility & bioactivity [29]. |

Table 2: Bioactivity of Ultrafiltration Fractions from Yak Whey Protein Hydrolysate

| Ultrafiltration Fraction(Molecular Weight) | α-amylase Inhibition(%) | XOD Inhibition(%) | ABTS Radical Scavenging(%) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 kDa | 22.06 | 17.15 | 69.55 | [28] |

| 1-3 kDa | Data not provided in source | Data not provided in source | Data not provided in source | |

| 3-5 kDa | Data not provided in source | Data not provided in source | Data not provided in source | |

| 5-10 kDa | Data not provided in source | Data not provided in source | Data not provided in source | |

| >10 kDa | Data not provided in source | Data not provided in source | Data not provided in source |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Protein Isolates

This protocol provides a generalized workflow for the enzymatic hydrolysis of protein isolates, which can be adapted based on the specific optimization data in Table 1.

1. Preparation of Experimental Materials and Reagents [30]

- Protein Sample: Use a purified protein isolate (e.g., Soy Protein Isolate, Mung Bean Protein Isolate). Ensure the sample is completely dissolved in an appropriate buffer. Determine protein concentration using a standard assay (e.g., Bradford assay).

- Protease: Select a suitable protease (e.g., Alkaline protease, Pepsin, Alcalase) and prepare an enzyme solution of known activity.

- Buffer Solution: Choose a buffer that maintains the optimal pH for the selected enzyme (e.g., Phosphate buffer for alkaline conditions).

- Other Reagents: Have acids (e.g., HCl) and bases (e.g., NaOH) on hand for pH adjustment during the reaction. Prepare reagents for reaction termination (e.g., another acid/base for pH shift, or a heating block for thermal inactivation).

2. Hydrolysis Reaction [27] [28] [29]

- Reaction Setup: In a reaction vessel, combine the protein solution with buffer to achieve a typical substrate concentration of 3-5% (w/v).

- Condition Equilibrium: Place the vessel in a temperature-controlled water bath or heating block and allow it to equilibrate to the optimal temperature for your enzyme (see Table 1).

- Initiation: Adjust the pH to the enzyme's optimum and then add the predetermined amount of enzyme (E/S ratio from Table 1) to start the hydrolysis. Gently stir the mixture throughout the reaction.

- Control and Monitoring: Maintain the pH stat by adding acid/base as needed. The reaction should proceed for the optimized time (see Table 1). You can periodically withdraw samples to monitor the Degree of Hydrolysis (DH).

3. Reaction Termination and Product Recovery [30] [29]

- Termination: After the desired time, terminate the reaction by rapidly inactivating the enzyme. This is typically done by:

- Separation: Cool the hydrolysate and centrifuge it (e.g., at 10,000× g for 20 minutes at 4°C) to remove any insoluble aggregates or denatured enzyme [29].

- Purification and Analysis: The supernatant contains your protein hydrolysate. It can be further fractionated by ultrafiltration [28] and then lyophilized for storage. Always perform QC checks on the final product [16].

Process and Quality Control Visualization

Enzymatic Hydrolysis Workflow

Protein QC for Research Reproducibility

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Enzymatic Hydrolysis and QC

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Proteases (e.g., Alkaline Protease, Pepsin, Alcalase, Trypsin) | Catalyze the cleavage of peptide bonds to hydrolyze proteins into smaller peptides [9] [27] [28]. | Select based on specificity, optimal pH (e.g., pepsin for acidic conditions), and the desired bioactivity of the resulting hydrolysate [27] [30]. |

| Ultrafiltration Membranes | Fractionate hydrolysates by molecular weight to isolate specific peptide sizes, remove bitter compounds, or concentrate samples [28]. | Choose membranes with appropriate molecular weight cut-offs (e.g., 1kDa, 3kDa, 10kDa) to target specific bioactive peptide fractions [28]. |

| Buffers (e.g., Tris, Phosphate, HEPES) | Maintain stable pH during hydrolysis and purification, which is critical for enzyme activity and protein stability [31]. | Tris is the most commonly used buffer in protein purification (49.2% of cases). Ensure compatibility with your enzyme's optimal pH range [31]. |

| Affinity Tags (e.g., Polyhistidine-tag) | Facilitate purification of recombinant proteins via immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) [31]. | The polyhistidine-tag is dominant (82.5% of cases). It enhances expression, solubility, and enables high-purity isolation [31]. |

| QC Instruments: SDS-PAGE, DLS, Mass Spectrometry | Assess protein purity, homogeneity/dispersity, and identity as minimal QC standards to ensure research reproducibility [16]. | These are essential for verifying that the protein/hydrolysate is correct, intact, and free of aggregates or contaminants before use in downstream applications [16]. |

Creating Hetero-Protein Systems for Functional Complementation

Within the scope of optimizing protein homogeneity and dispersity in purified samples, the creation of hetero-protein systems presents unique challenges. Functional complementation assays rely on the precise interaction of multiple, distinct protein subunits. The success and reproducibility of these experiments are fundamentally dependent on the quality of the individual protein components. Sample heterogeneity, such as the presence of aggregates, misfolded species, or unintended proteolytic fragments, can severely compromise functional data, leading to inaccurate conclusions about protein-protein interactions and complementation efficacy [16]. This technical support center is designed to guide researchers through common pitfalls, providing actionable troubleshooting advice to ensure the production of high-quality, homogeneous protein samples for reliable research outcomes.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My hetero-protein system shows no functional activity after purification. What are the primary causes I should investigate?

A1: A lack of activity can stem from several issues related to protein quality. First, confirm the identity and integrity of each protein in your system using mass spectrometry (e.g., intact protein mass measurement) to ensure the correct sequence and detect any proteolysis or major truncations [16]. Second, assess sample homogeneity and oligomeric state via size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) or dynamic light scattering (DLS). Aggregates or an incorrect oligomeric state can directly prevent functional complementation [16]. Third, verify that essential cofactors have not been removed during purification, and consider adding them back to the assay buffer [32].

Q2: I observe excessive protein degradation in my samples. How can I mitigate this?

A2: Protein degradation, a common issue that destroys homogeneity, can be minimized by:

- Performing all purification steps at 4°C and using pre-chilled buffers [7].

- Including protease inhibitors in all cell lysis and initial purification buffers [7].

- For recombinant proteins, ensuring the affinity tag is not being cleaved during processing. If degradation persists, check the construct design and consider using an N-terminal versus C-terminal tag or vice versa [7].

Q3: My His-tagged protein is not binding to the Ni-NTA resin. What could be wrong?

A3: This binding failure can occur for several reasons:

- The affinity tag is not accessible. If the His-tag is hidden due to protein folding, you may need to switch to denaturing purification conditions to expose the tag [7].

- Construct issues. Verify by DNA sequencing that there were no cloning errors and that the protein-coding region is in-frame with the tag [33].

- Low expression. Check the expression level of your construct via SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using an antibody against the affinity tag [33].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

The table below summarizes common problems, their potential causes, and solutions specifically for purifying components of hetero-protein systems.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Purification of Tagged Proteins for Hetero-Systems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No protein in eluate | Protein not expressing; tag inaccessible; protein degraded [7] [33] [32] | Sequence DNA construct; check expression via Western blot; use denaturing conditions; add protease inhibitors; ensure elution buffer is fresh and correctly prepared [7] [33]. |

| Low binding to affinity resin | Tag not accessible; binding conditions too stringent; resin compromised [7] [33] | Reduce flow rate or incubate sample with resin; reduce imidazole (1-5 mM) and/or NaCl (e.g., to 250 mM) in binding/wash buffer; if resin froze and formed clumps, replace it [7] [33]. |

| Contaminants co-elute with target | Wash conditions not stringent enough; non-specific binding [7] [33] [32] | Increase stringency of washes (e.g., increase [NaCl] to 2M, increase [imidazole]); add a mild non-ionic detergent (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100) to wash buffer; perform a second purification step [7]. |

| Protein precipitation/aggregation | Buffer conditions cause instability; shear stress [34] [32] | Optimize buffer pH and salt concentration; add stabilizing agents (e.g., glycerol); avoid vortexing and use wide-bore pipette tips to minimize shear stress; purify at room temperature if protein is stable [34]. |

| Low final protein yield | Protein not recovered in soluble fraction; expression level low; protein degradation [7] [35] | Solubilize protein complexes with mild, non-ionic detergents; optimize induction conditions (IPTG concentration, temperature, time); include protease inhibitors during lysis [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Homogeneity

Protocol: Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) for Assessing Homogeneity

This protocol is critical for evaluating the oligomeric state and dispersity of your purified protein samples, a key metric for functional studies [16].

1. Principle: SEC separates proteins based on their hydrodynamic radius, allowing the resolution of monomers, defined oligomers, and aggregates from each other.

2. Reagents and Buffers:

- SEC Running Buffer: 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5. Filter through a 0.22 µm membrane and degas before use.

- SEC Standards: A kit of proteins of known molecular weight for column calibration.

3. Procedure: 1. Equilibrate the SEC column with at least 2 column volumes (CV) of running buffer at a constant flow rate recommended for the column. 2. Clarify your protein sample by centrifugation at high speed (e.g., 14,000 x g for 10 minutes) to remove any insoluble material. 3. Concentrate the protein sample to a volume suitable for injection (typically 0.5-2% of the column CV). 4. Inject the sample onto the column and elute isocratically with running buffer, monitoring the UV absorbance (e.g., at 280 nm). 5. Collect fractions corresponding to distinct peaks.

4. Analysis:

- Analyze the chromatogram. A single, symmetric peak suggests a homogeneous preparation. Multiple peaks or broad, asymmetric peaks indicate heterogeneity (e.g., mixtures of oligomers or aggregates) [16].

- Analyze the fractions by SDS-PAGE to confirm the identity of the protein in each peak.

SEC Workflow for Homogeneity Assessment

Protocol: Quality Control for Recombinant Protein Identity and Purity

This protocol outlines the minimal QC tests recommended to ensure the quality of protein reagents, thereby improving research data reproducibility [16].

1. Purity Analysis by SDS-PAGE:

- Run an aliquot of the purified protein on a precast SDS-PAGE gel under reducing conditions.

- Stain the gel with Coomassie Blue or a more sensitive stain.

- A pure protein preparation should show a single major band at the expected molecular weight. Additional bands indicate contaminating proteins or proteolytic fragments.

2. Identity Confirmation by Mass Spectrometry (MS):

- Intact Protein MS: Determine the mass of the intact protein. This confirms the identity of the protein and detects whether it has suffered any proteolysis or post-translational modifications (micro-heterogeneity) [16].

- Tryptic Digest MS (Mass Fingerprinting): Digest the protein with trypsin and analyze the peptides by MS. This confirms the protein's identity and is especially useful if a host protein of similar mass was purified in error [16].

Table 2: Minimal Quality Control Tests for Protein Reagents [16]

| QC Test | Technique Examples | Key Information Provided |

|---|---|---|

| Purity | SDS-PAGE, Capillary Electrophoresis, Reversed-Phase LC | Presence of contaminating proteins or proteolytic fragments. |

| Homogeneity/Dispersity | Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Oligomeric state, presence of aggregates, sample monodispersity. |

| Identity | Mass Spectrometry (intact or tryptic digest) | Confirmation of correct protein sequence and intactness. |

Protein Quality Control Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents critical for successful protein purification and quality control in the context of creating hetero-protein systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Purification and QC

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Affinity Chromatography Resins | Selective binding and purification of tagged recombinant proteins (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins). |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Added to lysis and purification buffers to prevent protein degradation, preserving sample integrity [7]. |

| Detergents (e.g., NP-40, Triton X-100) | Aid in solubilizing membrane proteins or protein complexes; can be added to wash buffers to reduce non-specific binding [7]. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, TCEP, β-Mercaptoethanol) | Prevent oxidation of cysteine residues and the formation of unwanted disulfide bonds, which can cause aggregation [7] [34]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | Critical for separating proteins by size, assessing sample homogeneity, and removing aggregates [16]. |

| Gentle Elution Buffers | Near-neutral pH, high-salt buffers for eluting proteins from affinity resins while minimizing denaturation, helping to preserve activity for functional assays [7]. |

Buffer and Ionic Strength Optimization for Native-State Stability

FAQs: Core Concepts

1. How do buffer pH and ionic strength directly impact protein stability during purification? The stability of a protein's native state is highly dependent on its environment. Buffer pH affects the ionization of amino acid side chains, influencing the protein's net charge and conformational stability. Ionic strength, governed by salt concentration, modulates electrostatic interactions within the protein and between protein molecules. An optimal balance is required; if the ionic strength is too low, it may not sufficiently shield electrostatic repulsion, while if it's too high, it can disrupt essential salt bridges and promote aggregation due to a "salting-out" effect. The goal is to identify conditions that maximize the free energy difference (ΔG) between the folded and unfolded states [36] [4].

2. What is the relationship between a protein's isoelectric point (pI) and my choice of ion exchange chromatography media? The pI is a critical parameter for selecting ion exchange media. You should use a cation exchanger (e.g., SP, CM) when your protein is most stable below its pI, as it will carry a net positive charge. Conversely, use an anion exchanger (e.g., Q, DEAE) when your protein is stable above its pI, where it carries a net negative charge. If the protein is stable over a wide pH range on both sides of its pI, either type of exchanger can be used. For a systematic approach, start with a strong ion exchanger, which maintains its charge over a broad pH range [36].

3. Why is my protein not binding to the ion exchange column, and how can I fix it? This common issue can have several causes and solutions [37]:

- Incorrect Ionic Strength: The ionic strength of your sample may be too high. Solution: Desalt or dilute your sample with start buffer.

- Incorrect pH: The buffer pH may be inappropriate for binding. Solution: For an anion exchanger, increase the buffer pH; for a cation exchanger, decrease the pH.

- Detergent Contamination: The column may be contaminated with detergent, which can interfere with binding.

4. What are some affordable and readily available additives to stabilize my protein in solution? Several small molecules can improve protein stability and solubility without requiring a significant investment [4]. These are often used in the low mM to percent range and work through various mechanisms, such as preferential exclusion or stabilizing the protein's hydration shell.

- Amino Acids: L-Arginine, L-Glutamate, L-Proline, Glycine, L-Lysine.

- Sugars and Polyols: Sucrose, Glycerol, Sorbitol.

- Other Osmolytes: Betaine, Proline.

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Ionic Strength and Buffer Issues in IEX

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sample elutes before gradient begins (proteins do not bind) [37] | Sample ionic strength too high; incorrect pH | Desalt/dilute sample. For anion exchange, increase buffer pH; for cation exchange, decrease pH. |

| Proteins elute late in gradient (bind too strongly) [37] | Buffer pH suboptimal; gradient ionic strength too low | For anion exchange, decrease buffer pH; for cation exchange, increase pH. Use a steeper or higher ionic strength gradient. |

| Target protein(s) not resolved [37] | Poorly optimized conditions | Re-optimize pH and gradient slope. Consider using a different counter-ion (e.g., K+, acetate) to alter selectivity [36]. |

| Poor run-to-run reproducibility | Inconsistent buffer preparation | Prepare buffers at the temperature they will be used. Do not dilute pH-adjusted stock solutions. Record and follow exact preparation procedures [38]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Stability Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Strong Ion Exchangers (Q, SP) | Maintain charge capacity over a wide pH range, ideal for initial method development and screening [36]. |

| Chaotropic Salts (NaCl, KCl) | Act as counter-ions in IEX with a low "salting-out" effect, helping to maintain protein solubility during elution [36]. |

| Thermostability Assays (nanoDSF) | Measure thermal unfolding (Tm, Tonset, Tagg) by monitoring intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence, providing a direct readout of stability under different buffer conditions [39] [4]. |

| Stabilizing Additives (e.g., Arg, Sucrose) | Improve protein stability and solubility by altering the solvent environment, helping to maintain the native state and prevent aggregation [4]. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Assesses protein homogeneity, monodispersity, and aggregation state after purification and buffer optimization [39]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Initial Screen for IEX Binding Conditions

This protocol helps establish starting conditions for ion exchange purification [36].

Key Materials:

- Strong Anion Exchange medium (e.g., Q) and/or Strong Cation Exchange medium (e.g., SP)

- Start buffers: 20 mM Tris or HEPES, pH 8.0 (Anion Exchange); 20 mM MES or Phosphate, pH 6.0 (Cation Exchange)

- Elution buffer: Start buffer + 1 M NaCl

- Chromatography system capable of gradient elution

Methodology:

- Equilibrate: Pack a small column (e.g., 1 mL) and equilibrate with 5-10 column volumes (CV) of start buffer until the UV baseline, pH, and conductivity are stable.

- Prepare Sample: Adjust the sample to the pH and ionic strength of the start buffer using desalting, dialysis, or dilution.

- Apply and Wash: Apply the sample to the column. Wash with 5-10 CV of start buffer until the UV baseline is stable, ensuring all unbound material is removed.

- Elute: Elute bound proteins using a linear gradient of 0-100% elution buffer over 10-20 CV.

- Strip and Re-equilibrate: Wash the column with 5 CV of 1 M NaCl (100% elution buffer) to remove strongly bound impurities, then re-equilibrate with 5-10 CV of start buffer.

Visual Workflow: Ion Exchange Chromatography Screening

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Stability Screening Using nanoDSF

This protocol uses intrinsic protein fluorescence to measure thermal stability under different buffer conditions, helping to identify formulations that maximize native-state stability [39] [4].

Key Materials:

- nanoDSF-capable fluorimeter

- Purified protein sample

- Plate with 96 different buffer/additive conditions

- Capillary tubes or plate suitable for the instrument

Methodology:

- Sample Dilution: Dilute the purified protein from its storage condition into the various screening conditions. A tenfold dilution is often sufficient to observe stabilization or destabilization effects [39].

- Loading: Load the samples into capillaries or the wells of a nanoDSF plate.

- Thermal Ramp: Subject the samples to a controlled temperature ramp (e.g., from 20°C to 95°C) while monitoring the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence at 330 nm and 350 nm.

- Data Analysis: Plot the fluorescence ratio (350 nm/330 nm) or the signal at a single wavelength against temperature. Determine the melting temperature (Tm), which is the inflection point of the unfolding transition, and Tonset, the temperature where unfolding begins [39] [4].

- Selection: Prioritize buffer conditions that result in the highest Tm and Tonset values for downstream experiments.

Visual Workflow: High-Throughput Stability Screening

Solving Common Homogeneity Challenges: A Troubleshooter's Guide

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Membrane Proteins

Q1: Why is maintaining a native-like lipid environment so critical for membrane protein studies? The structure, function, and conformational flexibility of membrane proteins are intimately tied to their lipid environment [40]. Removing them from their native membrane can disrupt specific lipid-protein interactions, leading to protein denaturation, aggregation, and loss of function [41] [40]. Reconstitution into native-like membrane mimetics is essential for preserving biological activity during in vitro experiments [40].

Q2: What are the biggest hurdles in obtaining high-quality membrane protein samples? The primary challenges include:

- Low Abundance: Naturally low expression levels often require significant optimization of expression systems [41].

- Instability: Removal from the native lipid bilayer often renders the proteins unstable in aqueous solutions, leading to aggregation and precipitation [41] [40].

- Complex Extraction and Purification: The process of extracting proteins from the membrane with detergents or other agents without damaging their structure is technically demanding [41] [40].

Insoluble Aggregates

Q3: What causes insoluble aggregates to form in reconstituted protein samples? Insoluble aggregation can be triggered by stress during processing. For example, spray-drying proteins can disrupt their higher-order structure, exposing hydrophobic regions that drive aggregation through hydrophobic interactions upon reconstitution [42]. Similar mechanisms can occur due to shear stress, air-liquid interfaces, or freeze-thaw cycles.

Q4: How can I confirm that observed particles are insoluble protein aggregates and not something else? A combination of techniques is used. Microflow Imaging (MFI) can count and size particles [42]. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) microscopy can then confirm the proteinaceous nature of the collected particles, distinguishing them from undissolved excipients or other contaminants [42].

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs)

Q5: My protein sample lacks a stable 3D structure. Does this mean it is degraded or non-functional? Not necessarily. Many proteins or protein regions, known as Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) or Regions (IDRs), are biologically active without adopting a fixed three-dimensional structure [43] [44]. This is known as the "disorder–function paradigm" [44]. You should validate functionality using activity assays specific to your protein.

Q6: How do I characterize a protein that is inherently unstructured? Techniques that study conformational ensembles are ideal. These include:

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Provides atomic-resolution data on dynamics and transient structures [43].

- Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS): Probes conformational dynamics and solvent accessibility, which can also be applied to study regions involved in aggregate formation [42].

- Analytical Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (MALS): Determines the hydrodynamic radius and molecular weight of polydisperse samples, providing information on oligomeric state and dispersity [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Membrane Protein Purification and Stability

This guide addresses common issues encountered when working with membrane proteins.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Membrane Protein Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Experimental Controls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Expression | Protein toxicity to host; improper folding. | Use different expression hosts (e.g., insect, mammalian cells); optimize induction conditions [41]. | Test small-scale expressions; use a tagged protein for detection. |

| Low Stability & Activity | Loss of native lipid environment; use of harsh detergents. | Screen different detergents and lipids; use membrane mimetics like nanodiscs for reconstitution [41] [40]; add stabilizing lipids during purification. | Measure activity immediately after purification and over time. |

| Sample Aggregation | Denaturation during extraction; detergent instability; hydrophobic exposure. | Use milder detergents; incorporate lipids early in purification; optimize buffer conditions (pH, salt) [40]. | Analyze by SEC-MALS or DLS to monitor size and dispersity [16]. |

| Low Functional Yield | Only a fraction of the purified protein is active. | Perform activity assays parallel to concentration measurements; use traceable affinity tags for accurate quantification [16]. | Determine specific activity (activity per mg protein). |

Troubleshooting Insoluble Aggregates

This guide focuses on identifying and mitigating the formation of insoluble aggregates.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Insoluble Aggregate Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Analytical Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Particle Counts | Shear stress; surface-induced denaturation; contaminant nucleation. | Avoid vigorous mixing; use surfactants to protect interfaces; use ultra-pure buffers and filter solutions [42]. | Microflow Imaging (MFI) [42]; Light Obscuration. |

| Aggregates after Processing | Stress from drying, freezing, or temperature shifts. | Optimize process parameters (e.g., lower outlet temp in spray-drying) [42]; use cryoprotectants for freeze-thaw. | Compare SEC chromatograms before and after processing [42]. |

| Identification of Particles | Uncertainty about particle composition (protein vs. other). | Isolate particles and analyze their composition. | FTIR Microscopy (for proteinaceous nature) [42]; SDS-PAGE. |

| Understanding Aggregation Mechanism | Unknown structural region initiating aggregation. | Probe conformational changes in the aggregated state. | Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) [42]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quality Control for Purified Protein Samples

Implementing this minimal set of quality control (QC) tests is essential for ensuring reproducible and reliable experimental data [16].

Table 3: Minimal Quality Control Tests for Protein Reagents [16]

| QC Test | Method | Purpose | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purity | SDS-PAGE, Capillary Electrophoresis (CE), Reversed-Phase LC (RPLC) | Assess sample purity and detect proteolysis or contaminating proteins. | A single major band at expected molecular weight; minimal contaminating bands. |