Molecular Chaperones in Proteostasis: Mechanisms, Disease Connections, and Therapeutic Targeting

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role molecular chaperones play in cellular protein quality control.

Molecular Chaperones in Proteostasis: Mechanisms, Disease Connections, and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role molecular chaperones play in cellular protein quality control. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental mechanisms of chaperone-assisted folding, the consequences of proteostasis failure in diseases like neurodegeneration and cancer, and the advanced methodologies used to study these processes. Furthermore, it evaluates current and emerging therapeutic strategies, including small-molecule inhibitors and artificial chaperone systems, that target the proteostasis network to combat a growing list of human diseases, synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge clinical applications.

The Proteostasis Guardians: Defining Molecular Chaperones and Their Core Mechanisms

This whitepaper delineates the pivotal historical milestones in the understanding of protein quality control, tracing the trajectory from the serendipitous discovery of the heat shock response to the formulation of the sophisticated proteostasis network concept. Framed within a broader thesis on the role of molecular chaperones, we examine how this field has evolved from observing chromosomal "puffing" in Drosophila to defining a complex cellular system of nearly 3,000 components in humans. The review synthesizes fundamental discoveries, key experimental methodologies, and the emerging therapeutic paradigms that target the proteostasis network for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and other age-onset pathologies. By integrating quantitative data and structural visualizations, this guide provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this critical area of cell biology.

The faithful execution of biological function relies on the proteome—the entire complement of proteins expressed by a cell. For proteins to be functional, they must adopt precise three-dimensional conformations, a process known as protein folding. While pioneering work by Christian Anfinsen demonstrated that the amino acid sequence encodes all information necessary for spontaneous folding in vitro, the reality inside the cell is far more complex [1]. The cellular environment is densely crowded, favoring non-specific interactions between the hydrophobic regions of partially folded polypeptides, which can lead to misfolding and irreversible aggregation [2] [1]. Furthermore, the translation of proteins by the ribosome is a slow process relative to folding kinetics, leaving nascent chains particularly vulnerable to misfolding [1].

To navigate these challenges, cells have evolved an elaborate machinery of molecular chaperones—helper proteins that assist in the folding, assembly, and maintenance of other proteins without becoming part of their final structure [1]. The discovery of this machinery began with observations of a generalized stress response and has since matured into the concept of the proteostasis network (PN), an integrated system that manages protein synthesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation to maintain proteome health across the lifespan of the cell and organism [3].

Key Historical Milestones

The conceptual framework of protein quality control has been built upon a series of foundational discoveries. The table below chronicles the major milestones that have shaped our current understanding.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Protein Quality Control Research

| Year | Milestone Discovery | Key Researchers/Group | Experimental Model | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Discovery of the Heat Shock Response | Ferruccio Ritossa [4] [5] | Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) | Observed chromosomal "puffing" pattern after temperature increase, indicating activation of specific genes. |

| 1970s-80s | Identification of Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs) | Multiple groups [6] | D. melanogaster, E. coli | The proteins expressed after heat shock were identified and classified (e.g., Hsp70, Hsp90). |

| 1984 | Recognition of Hsp70 Conservation | Bardwell & Craig [4] | D. melanogaster, E. coli, S. cerevisiae | Demonstrated high sequence similarity between bacterial DnaK and eukaryotic Hsp70, revealing deep evolutionary conservation. |

| 1993 | First Crystal Structure of an Hsp70 | Not Specified [6] | N/A | Structure of HSC70 (PDB: 1ATR) solved, providing first atomic-level insight into chaperone machinery. |

| 2006 | Formalization of Protein Quality Control Concept | Hartl & Hayer-Hartl [7] | N/A | Comprehensive review articulating chaperones as central players in cellular quality control against misfolding/aggregation. |

| 2010s | Emergence of the Proteostasis Network Concept | Balch, Morimoto, et al. [3] | Mammalian cells | Defined the PN as the integrated system of ~2000 components governing synthesis, folding, & degradation. |

| 2019-2025 | Elucidation of Complex Chaperone Structures & Mechanisms | Kalodimos et al. [8], Multiple groups [6] | Bacteria, Yeast, Human | Solved high-resolution structures of full-length Hsp70-Hsp40 complexes and Hsp90 multi-component "epichaperone" complexes. |

The Initial Discovery: A Serendipitous Laboratory Incident

The field originated not from a hypothesis-driven experiment, but from an astute observation. In the 1960s, Ferruccio Ritossa was studying chromosome structure in Drosophila when a lab technician inadvertently increased the incubation temperature of the fruit flies. Upon examining the salivary gland chromosomes, Ritossa noticed a distinct "puffing pattern"—a cytological manifestation of intensely activated genes [4] [5]. This was the first record of the heat shock response, though the proteins responsible were not identified until the following decade.

From Phenomenon to Molecular Players: Identifying the Heat Shock Proteins

Subsequent work in the 1970s and 80s focused on identifying the proteins induced by heat shock. It was found that this response was not limited to heat but could be triggered by various proteotoxic stresses, including exposure to heavy metals, oxidative stress, and nutrient deprivation [4] [5]. These induced proteins were termed heat shock proteins (HSPs), classified by their molecular weight (e.g., Hsp70, Hsp90, Hsp40). A pivotal conceptual leap was the realization that these HSPs were not merely stress-induced but functioned as molecular chaperones under normal physiological conditions, guiding the proper folding of other proteins [1].

Conceptual Evolution to Proteostasis Network

The term "proteostasis" (protein homeostasis) was coined to describe the integrated biological pathways within a cell that control the biogenesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation of proteins present within and outside the cell [3]. This framework recognizes that the PN is composed of three core, interconnected modules:

- Protein Synthesis: Ribosomes and associated factors.

- Folding and Conformational Maintenance: Molecular chaperones and cochaperones.

- Protein Degradation: The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy-lysosomal pathway (ALP) [3].

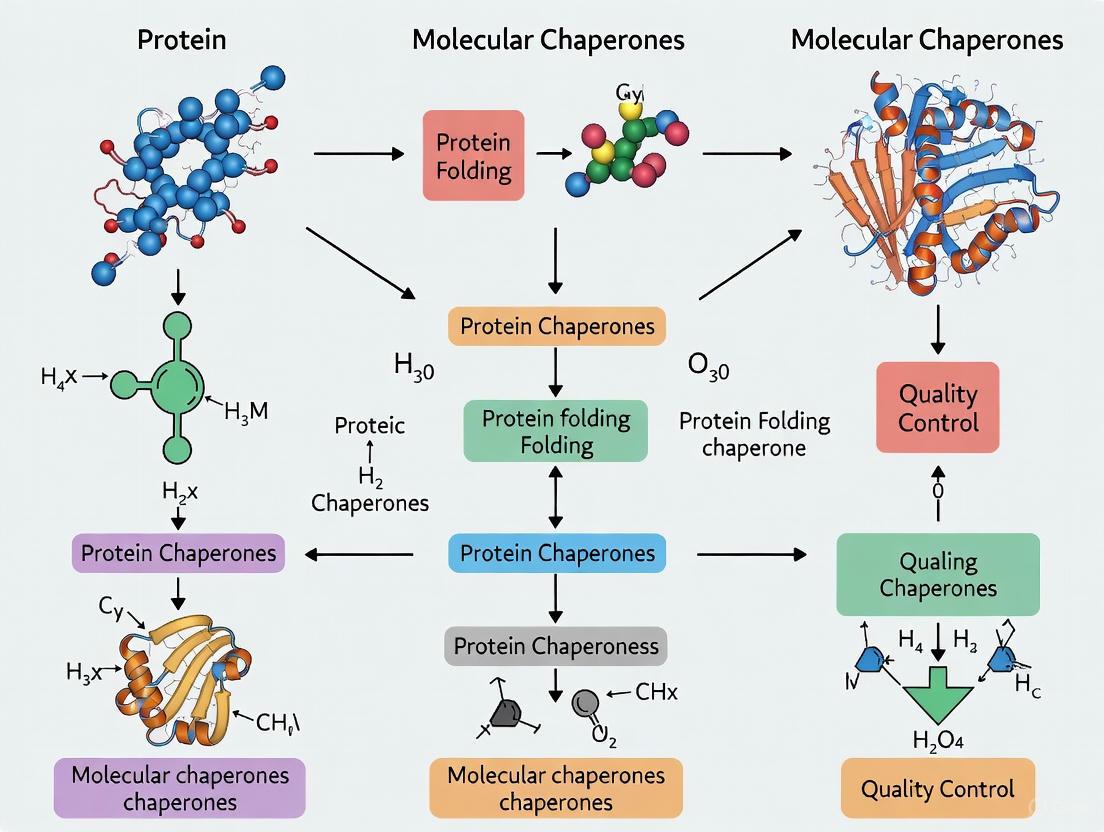

In human cells, this network is estimated to comprise nearly 3,000 unique components, organized into specialized branches for different organelles, reflecting the complexity of the human proteome [9]. The diagram below illustrates the logical progression from the initial stress trigger to the modern understanding of the proteostasis network.

Detailed Experimental Methodologies

Understanding these milestones required the development and application of sophisticated experimental techniques. The following section details key methodologies that have been foundational to the field.

Classic Genetic and Molecular Biological Workflows

Early experiments relied heavily on genetic models and indirect observations of protein function.

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols in Chaperone Research

| Methodology | Protocol Description | Key Insight Generated | Critical Reagents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Screening & Mutation | Isolation of mutant organisms (e.g., yeast, flies) with defective stress responses; mapping and characterizing the affected genes. | Identified essential chaperone genes (e.g., DnaK, DnaJ in E. coli) and their non-redundant functions in viability. | Mutagenic agents (EMS), Selective growth media, Gene sequencing tools. |

| Pulse-Chase Analysis & Immunoprecipitation | Cells are pulsed with labeled amino acids (e.g., S³⁵-methionine) then "chased" with unlabeled ones. Proteins are isolated at time points via immunoprecipitation. | Allowed tracking of a protein's folding, maturation, and degradation kinetics in living cells, showing chaperone involvement. | Radiolabeled amino acids, Antibodies against target protein/chaperone, Protein A/G beads. |

| Gene Expression Analysis | Northern blotting or RT-PCR to measure mRNA levels of HSP genes under stress vs. normal conditions. | Quantified the induction of the heat shock response and identified the specific HSP family members involved. | RNA extraction kits, Specific cDNA probes, Reverse transcriptase, PCR reagents. |

Modern Structural Biology and Biophysical Approaches

Recent breakthroughs have come from directly visualizing chaperone-client interactions. A landmark 2025 study by Kalodimos et al. exemplifies this approach [8].

Protocol: Determining Full-Length Chaperone Complex Structures via an Integrated Approach

- Protein Complex Reconstitution: Full-length bacterial Hsp40 (DnaJ) and Hsp70 (DnaK) were expressed and purified. A misfolded client peptide was added to form the functional complex.

- Multi-Method Data Collection:

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): Frozen, vitrified samples were imaged to generate low-resolution 3D maps of the large, flexible complexes.

- X-ray Crystallography: Smaller, stable domains and sub-complexes were crystallized to obtain high-resolution atomic structures.

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Used to study the dynamics and structure of flexible regions, like the G/F-rich domain of Hsp40, in solution.

- Hybrid Model Building: The high-resolution structures from crystallography and NMR were fitted into the lower-resolution volumetric maps from Cryo-EM to build a complete atomic model of the full-length complex.

- Functional Validation: Mutations were introduced into key structural elements (e.g., the phenylalanine in the Hsp40 G/F region) to disrupt the interface, confirming the mechanistic model through biochemical ATPase and client refolding assays.

This integrated protocol was crucial for overcoming the technical challenges of studying large, dynamic chaperone machines, ultimately revealing the "handoff" mechanism where Hsp40 transfers a client protein to Hsp70 [8]. The workflow is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Progress in this field has been enabled by a specific set of research tools and reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Protein Quality Control Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant HSP70 | Purified, often tagged, protein for in vitro studies. | Used in binding assays to identify client proteins and in structural studies (e.g., [10]). |

| Anti-Hsp70 Antibodies | Detect and quantify Hsp70 expression and localization. | Used in Western blotting, immunofluorescence, and Immunohistochemistry (e.g., staining human colon tissue [4]). |

| Hsp70/Hsp90 Inhibitors | Small molecules that disrupt chaperone ATPase activity or co-chaperone interaction. | Tool compounds to probe chaperone function in disease models (e.g., cancer cells [6]). |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Introduce specific point mutations into chaperone genes. | Used to validate functional mechanisms by disrupting key residues (e.g., Hsp40 G/F domain Phe [8]). |

| Radiolabeled Amino Acids (e.g., S³⁵-Methionine) | Track newly synthesized proteins in pulse-chase experiments. | Measure the folding kinetics and half-life of chaperone clients [1]. |

Structural and Mechanistic Insights into Chaperone Function

Structural biology has been instrumental in moving from phenomenological observation to mechanistic understanding.

Hsp70 Architecture and Allostery

Hsp70 chaperones share a conserved domain architecture that functions as an allosteric machine:

- N-terminal Nucleotide-Binding Domain (NBD): Binds and hydrolyzes ATP.

- Substrate-Binding Domain (SBD): Contains a β-sheet "bucket" that captures hydrophobic client peptides.

- C-terminal "Lid" Region: A helical segment that opens and closes over the SBD, regulating client binding affinity [5].

The conformational state is regulated by ATP hydrolysis: ATP-bound Hsp70 has an open lid and fast client binding/release kinetics, while ADP-bound Hsp70 has a closed lid and tightly binds the client [5]. This cycle is regulated by co-chaperones: Hsp40 (a J-protein) stimulates ATP hydrolysis, while nucleotide exchange factors (e.g., BAG-1) promote ADP release and return to the ATP-bound state [5].

The Hsp70-Hsp40 Handoff Mechanism Visualized

The 2025 structural study of the full-length bacterial Hsp70-Hsp40 complex revealed the precise mechanism of client transfer [8]. A key finding was the role of a glycine/phenylalanine-rich (G/F) region in Hsp40. The mechanism involves a specific phenylalanine residue from Hsp40's G/F region that inserts into the substrate-binding pocket of Hsp70, acting as a placeholder. During the handoff, the misfolded client protein displaces this phenylalanine, taking its place in the binding pocket. Subsequent ATP binding to Hsp70 induces a conformational change that ejects the client and resets the cycle [8]. The following diagram illustrates this process.

Implications for Disease and Therapeutic Development

The link between proteostasis failure and human disease has made chaperones attractive therapeutic targets.

- Neurodegenerative Diseases: Aggregation of misfolded proteins is a hallmark of Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's diseases. A decline in PN capacity, particularly during aging, contributes to pathogenesis [3] [1]. Recombinant Hsp70 has shown protective effects in models of Alzheimer's and stroke [10].

- Cancer: Cancer cells are under proteotoxic stress due to rapid proliferation and mutated proteins. They often overexpress Hsp70 and Hsp90 to support oncoprotein stability and inhibit apoptosis [5] [6]. Hsp70 overexpression is linked to poor prognosis in several cancers [5].

- Therapeutic Strategies: Drug development has evolved through stages: 1) Pan-HSP inhibitors (e.g., Hsp90 ATPase inhibitors); 2) Isoform-selective inhibitors; 3) Protein-protein interaction (PPI) disruptors (e.g., blocking Hsp70-Hsp40 interface); and 4) Multi-specific molecules [6]. Targeting tumor-specific chaperone complexes, or "epichaperones," is a promising new avenue [2] [6].

The journey from observing a heat-induced puff in a fruit fly chromosome to defining a network of nearly 3,000 human genes represents a remarkable achievement in molecular biology. The historical milestones underscore a fundamental biological truth: cells invest immense resources in maintaining proteome balance. The PN is not a simple collection of redundant components but a finely tuned, adaptive system.

Future research will focus on understanding the PN's plasticity—how it is rewired during cell differentiation, aging, and in response to chronic disease [3]. Therapeutically, the challenge is to move beyond general inhibition and towards the precise modulation of specific PN nodes or interactions to correct proteostasis defects in a patient- and disease-specific manner. The continued integration of structural biology, systems-level analysis, and disease modeling will be critical for realizing the goal of targeting the proteostasis network to treat a wide array of human diseases.

Molecular chaperones are a diverse class of proteins that facilitate the folding, assembly, translocation, and degradation of other proteins to maintain cellular protein homeostasis (proteostasis). They function as essential components of the cellular quality control system, preventing protein aggregation and assisting in the recovery of misfolded proteins, particularly under stress conditions [2]. The major ATP-dependent chaperone families include Hsp70, Hsp90, and chaperonins, while small heat shock proteins (sHSPs) function as ATP-independent chaperones. These chaperone systems collectively ensure proteome integrity and functionality, with their dysfunction being implicated in numerous diseases, including neurodegeneration and cancer [11] [6].

The Hsp70 Chaperone System

Structural Organization and Functional Mechanism

The 70 kDa heat shock protein (Hsp70) system consists of Hsp70 itself, J-proteins (Hsp40s), and nucleotide exchange factors (NEFs). Hsp70 is composed of two primary domains: an N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) that binds and hydrolyzes ATP, and a C-terminal substrate-binding domain (SBD) that interacts with client proteins through recognition of short, exposed hydrophobic stretches [12]. The ATPase cycle of Hsp70 is regulated by two classes of co-chaperones: J-proteins (Hsp40s) that stimulate ATP hydrolysis, and NEFs that promote ADP release and subsequent ATP binding [2].

Hsp70 exhibits two distinct chaperone functions: (1) an ATP-dependent foldase activity that actively promotes refolding of misfolded proteins to their native conformations, and (2) an ATP-independent holdase activity that prevents the accumulation of misfolded proteins by maintaining them in soluble, folding-competent states [13]. This functional versatility makes Hsp70 one of the most versatile chaperone systems in the cell, involved in processes ranging from de novo protein folding at the ribosome to protein translocation across membranes and cooperation with other chaperone systems [2].

Experimental Analysis of Hsp70 Function

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Hsp70 Functional Analysis

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| ATPase Assay Kits | Quantify Hsp70 ATP hydrolysis activity | Measure foldase function kinetics [13] |

| Luciferase Refolding Assay | Model client protein for folding studies | Monitor Hsp70-assisted reactivation of denatured firefly luciferase [14] |

| Recombinant Hsp40 (DnaJ) | Co-chaperone stimulating ATPase activity | Study Hsp70-Hsp40 collaboration in refolding [6] |

| Nucleotide Exchange Factors (NEFs) | Promote ADP release from Hsp70 | Investigate complete ATPase cycle regulation [12] |

| CHIP Ubiquitin Ligase | Connects Hsp70 to degradation pathways | Study client fate decision (folding vs. degradation) [15] |

Diagram 1: The Hsp70 chaperone cycle, showing conformational changes regulated by ATP binding/hydrolysis and co-chaperone interactions.

The Hsp90 Chaperone System

Structural Dynamics and Client Maturation

Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) functions as a homodimer, with each monomer consisting of three domains: the N-terminal domain (NTD) that binds and hydrolyzes ATP, the middle domain (MD) that participates in client protein binding and contributes a catalytic arginine residue for ATPase activity, and the C-terminal domain (CTD) that mediates dimerization [12]. Hsp90 undergoes dramatic ATP-dependent conformational changes, transitioning between an open, V-shaped conformation when ATP-free and a closed conformation upon ATP binding where the NTDs dimerize and associate with the MDs [13].

Unlike more generalist chaperones, Hsp90 interacts with a specific set of "client" proteins—many of which are signal transducers such as kinases and transcription factors—and is responsible for their final stages of maturation, stabilization, and activation [12] [6]. The conformational cycle of Hsp90 is regulated by numerous co-chaperones that assemble into distinct complexes to modulate Hsp90's ATPase activity, client binding, and progression through the chaperone cycle.

Coordinated Regulation with Hsp70

Hsp90 often functions downstream of Hsp70 in a coordinated chaperone pathway. The transfer of client proteins from Hsp70 to Hsp90 is facilitated by the co-chaperone Hop (Hsp70-Hsp90 organizing protein), which simultaneously binds both chaperones to form a functional ternary complex [12]. Recent evidence indicates that eukaryotic Hsp70 and Hsp90 can also form a prokaryote-like binary chaperone complex in the absence of Hop, with this simplified complex displaying enhanced protein folding and anti-aggregation activities [12].

Table 2: Hsp90 Client Protein Classes and Regulatory Co-chaperones

| Client Class | Representative Members | Key Regulatory Co-chaperones | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinases | v-Src, Cdk4, BRAF | Cdc37, PP5 | Activation, maturation, and stabilization [6] |

| Transcription Factors | Glucocorticoid Receptor, p53 | Hop, p23 | Ligand-binding competence [13] [12] |

| Steroid Hormone Receptors | Estrogen Receptor, Androgen Receptor | FKBP, p23 | Maturation and regulation [12] |

| Proteasome Subunits | 26S/30S Proteasome | Hop | Assembly and stability [12] |

Diagram 2: The Hsp90 chaperone cycle, showing client transfer from Hsp70 and ATP-dependent conformational changes.

Small Heat Shock Proteins (sHSPs)

Structural Features and Holdase Function

Small heat shock proteins (sHSPs) are ATP-independent chaperones that range in size from 12-43 kDa and represent the first line of defense in protein homeostasis [6]. Ten sHSP members (HSPB1-HSPB10) have been identified in mammals, characterized by a conserved α-crystallin domain flanked by variable N-terminal and C-terminal sequences [16] [6]. The α-crystallin domain forms a β-sheet sandwich structure consisting of eight antiparallel strands, which serves as the structural core for dimer formation [6].

sHSPs function primarily as holdases that bind non-native proteins to prevent their aggregation, maintaining clients in a soluble, folding-competent state for subsequent refolding by ATP-dependent chaperone systems like Hsp70 [13] [16]. Their chaperone activity is regulated by their dynamic quaternary structure, with smaller oligomers generally representing the more active chaperone species [2]. The variable N- and C-terminal regions are indispensable for sHSP subunit interactions and the formation of higher-order oligomers [6].

Substrate Recognition and Regulation

sHSPs demonstrate a remarkable ability to recognize a wide range of non-native substrate proteins while showing preference for certain functional classes of proteins. In prokaryotes, sHSPs preferentially protect translation-related proteins and metabolic enzymes, which may explain their critical role in enhancing cellular stress resistance [16]. Mechanistically, prokaryotic sHSPs possess numerous multi-type substrate-binding residues that are hierarchically activated in a temperature-dependent manner, allowing them to function as temperature-regulated chaperones [16].

Table 3: Characteristics of Major Mammalian Small Heat Shock Proteins

| sHSP Member | Also Known As | Reported Structural Features | Cellular Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSPB1 | HSP27 | Forms dynamic 24-mers; disordered N-terminus | Stress resistance, actin dynamics [6] |

| HSPB5 | αB-crystallin | Stable 24-32 mers; eye lens predominant | Lens transparency, cytoskeletal organization [6] |

| HSPB6 | HSP20 | Regulated oligomerization | Muscle function, cardiovascular protection [6] |

| Mitochondrial Hsp22 | - | Interacts with ATP synthase machinery | Mitochondrial proteostasis [17] |

Chaperonins: Assisted Folding in a Confined Chamber

Chaperonins are large, barrel-shaped multi-subunit complexes that provide a confined environment for protein folding. They are classified into two groups: Group I chaperonins (including GroEL in bacteria and Hsp60 in eukaryotes) function with a co-chaperone lid (GroES in bacteria), while Group II chaperonins (such as TRiC/CCT in eukaryotes) contain built-in lid structures [2]. These complexes facilitate folding by isolating non-native proteins within their central cavity, thereby preventing aggregation and allowing folding to proceed unimpeded by the crowded cellular environment.

The chaperonin reaction cycle is driven by ATP binding and hydrolysis, which induces conformational changes that close the folding chamber, then open it to release the folded protein. This mechanism is particularly essential for the folding of proteins with complex folding pathways or those prone to aggregation, including approximately 10% of cytosolic proteins in eukaryotes, with certain essential proteins being obligate chaperonin clients [2].

Post-Translational Modifications: The Chaperone Code

Regulatory Mechanisms and Functional Consequences

The activities of molecular chaperones are finely tuned by post-translational modifications (PTMs) that create a sophisticated "chaperone code" governing client fate, drug sensitivity, and cellular stress responses [18]. Hsp70 and Hsp90 undergo various PTMs including phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, ubiquitination, and glycosylation, which dynamically regulate their ATPase activity, subcellular localization, and interactions with both clients and co-chaperones [18].

A key regulatory mechanism involves phosphorylation at the C-termini of Hsp70 and Hsp90, which serves as a molecular switch that alters their binding preference for specific co-chaperones. Phosphorylation prevents binding to the ubiquitin ligase CHIP while enhancing interaction with HOP, thereby shifting the balance from protein degradation toward folding and maturation [15]. This PTM-based regulatory system introduces remarkable complexity and flexibility into chaperone function, with particular significance in cancer, neurodegeneration, and inflammation [18].

Diagram 3: The "chaperone code" where post-translational modifications determine client protein fate by regulating co-chaperone binding.

Research Methods and Experimental Applications

Methodologies for Chaperone Function Analysis

Investigating chaperone function requires integrated methodological approaches that span biochemical, structural, and cellular techniques. ATPase activity assays are fundamental for characterizing the enzymatic function of Hsp70 and Hsp90, typically measured using colorimetric or coupled enzymatic systems that quantify phosphate release [13]. Client refolding assays employ model substrate proteins like firefly luciferase or citrate synthase that are chemically denatured then monitored for chaperone-assisted reactivation, providing direct measurement of foldase activity [13] [14].

For holdase function analysis, aggregation suppression assays track the precipitation of aggregation-prone clients (such as insulin or α-synuclein) by measuring light scattering or using sedimentation approaches [13]. Structural characterization of chaperone-client interactions employs nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, X-ray crystallography of chaperone-client complexes, and increasingly, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) for visualizing large, dynamic chaperone assemblies [13] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Core Research Reagent Solutions for Chaperone Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATPase Inhibitors | Radicicol (Hsp90); VER-155008 (Hsp70) | Mechanistic studies, therapeutic exploration | Blocks ATP binding/hydrolysis to trap conformational states [6] |

| Co-chaperone Proteins | Recombinant Hop, Cdc37, p23, CHIP | Pathway mapping, client fate studies | Define specific functional pathways within chaperone networks [12] [15] |

| Model Client Proteins | Luciferase, Glucocorticoid Receptor, tau, α-synuclein | Folding, holdase, disaggregase assays | Well-characterized substrates for functional quantification [13] [14] |

| Phospho-specific Antibodies | Anti-pS189 Hop, Anti-pT198 Hop, Hsp90 C-terminal phospho-antibodies | PTM mapping, signaling studies | Detect regulatory modifications in chaperone circuits [15] |

| Aggregation-Prone Proteins | Insulin, α-synuclein, Aβ peptide | Holdase and anti-aggregation assays | Measure prevention of protein aggregation [13] |

Molecular chaperones represent promising therapeutic targets for numerous human diseases, with cancer and neurodegenerative disorders being primary areas of investigation. In cancer, malignant cells frequently exploit chaperone function to support oncogenic signaling, buffer proteotoxic stress, and promote survival. Consequently, Hsp90 inhibitors have been extensively explored as anticancer agents, with some advancing to clinical trials [6]. Conversely, in neurodegenerative diseases characterized by protein aggregation, enhancing chaperone function represents a potential therapeutic strategy to reduce proteotoxicity [13].

The complex regulation of chaperones through PTMs and co-chaperone interactions provides multiple entry points for therapeutic intervention beyond simple inhibition of ATPase activity. Emerging strategies include targeting specific co-chaperone interactions, modulating the "chaperone code" by influencing PTM-writing or -erasing enzymes, and developing compounds that allosterically regulate chaperone function [18] [6]. As our understanding of the intricate chaperone networks continues to deepen, so too will opportunities for developing precisely targeted therapies that restore proteostasis in disease contexts.

Within the cellular proteostasis network, ATP-dependent molecular chaperones are fundamental components that prevent protein misfolding and aggregation, thereby ensuring cellular viability [19]. These chaperones are essential for navigating the challenges of the intracellular environment, such as macromolecular crowding and high rates of protein synthesis, which inherently favor non-productive interactions [19]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of two major ATP-dependent chaperone systems: the Hsp70 system and the GroEL/GroES chaperonin machine. The Hsp70 system, including co-chaperones Hsp40 and NEFs, operates as a versatile "molecular clamp" that binds short hydrophobic peptides to assist in a wide array of folding processes [20] [21]. In contrast, the GroEL/GroES system forms a "nano-cage" that encapsulates single protein molecules, providing a secluded environment for folding to proceed in isolation [22] [23]. By detailing their distinct mechanisms, kinetic parameters, and experimental methodologies, this review aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with a refined understanding of these critical cellular machines and their implications in health and disease.

The Hsp70 Chaperone System

Core Components and the ATPase Cycle

The Hsp70 chaperone system is a central hub in the cellular protein quality control network, assisting in processes ranging from de novo folding and refolding of misfolded proteins to membrane translocation and dissolution of protein aggregates [20] [24]. Hsp70 chaperones function as ATP-dependent "foldases" and "holdases," with their activity regulated by a cycle of nucleotide binding and hydrolysis [25].

The functional core of the system consists of:

- Hsp70: A monomeric chaperone comprising an N-terminal Nucleotide-Binding Domain (NBD) with ATPase activity and a C-terminal Substrate-Binding Domain (SBD) that interacts with hydrophobic peptide segments of client proteins [20] [21].

- Hsp40 (J-domain proteins): Co-chaperones that stimulate Hsp70's ATPase activity and often serve as primary recruiters of non-native substrate proteins [20] [21].

- Nucleotide Exchange Factors (NEFs): Proteins such as Bag domains, HspBP1, and Hsp110 that catalyze the exchange of ADP for ATP, resetting the Hsp70 cycle and promoting substrate release [21].

The ATPase cycle of Hsp70 is the fundamental engine driving its chaperone function, as illustrated in the diagram below:

In the ATP-bound state, Hsp70 exhibits low affinity for substrates and rapid binding and release kinetics, allowing the SBD to sample potential client proteins [20] [21]. Upon ATP hydrolysis, stimulated by Hsp40 and substrate binding, the chaperone undergoes a conformational change to the ADP-bound state, which has high substrate affinity and traps the client protein [20]. Finally, nucleotide exchange, catalyzed by NEFs, promotes ADP release and ATP rebinding, returning Hsp70 to its low-affinity state and releasing the substrate for a folding attempt [21]. This cycle can be repeated until the substrate reaches its native conformation or is handed off to downstream components of the proteostasis network.

Quantitative Kinetic Parameters of Hsp70

The following table summarizes key kinetic and biophysical parameters for the Hsp70 system, specifically for the human BiP protein, as revealed by recent investigations:

Table 1: Kinetic and Biophysical Parameters of the Hsp70 Chaperone BiP

| Parameter | Value | Experimental Method | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| KD (ADP) | 0.9 ± 0.1 μM | ITC & NMR Titration [24] | Very high affinity in product state; dictates cycle lifetime. |

| KD (ATP) | 1.6 ± 0.2 μM | ITC & NMR Titration [24] | High affinity for substrate ATP; ensures cycle progression. |

| KD (Pi) | 310 ± 40 μM | ITC & NMR Titration [24] | Low affinity for inorganic phosphate; facilitates product release. |

| KD (ADP·Pi) | 280 ± 50 μM | ITC & NMR Titration [24] | Low affinity for the hydrolyzed products. |

| Product Release Pathways | Two parallel pathways (ADP or Pi released first) | In-cyclo NMR [24] | Provides regulatory flexibility under varying cellular [ADP]/[Pi] ratios. |

Key Experimental Workflow: In-Cyclo NMR for Hsp70 Cycle Analysis

A recent breakthrough in studying the Hsp70 functional cycle is the development of the "in-cyclo NMR" method, which combines high-resolution NMR spectroscopy with an ATP recovery and phosphate removal system [24]. This setup allows for the simultaneous determination of kinetic rates and structural information throughout the ATP-driven functional cycle.

Detailed Protocol for In-Cyclo NMR [24]:

Sample Preparation:

- Express and purify the target protein (e.g., the NBD of human BiP).

- Implement a high-purity protocol involving an affinity column step under denaturing conditions (8 M urea) to remove bound nucleotides and contaminants.

- Refold the protein via slow dialysis and confirm native state formation using SEC-MALS and NMR.

- Prepare an isotope-labeled sample with protonated methyl groups (Ile, Val, Met) on a deuterated background for high-sensitivity NMR.

NMR Resonance Assignment:

- Acquire 2D [13C,1H]-methyl-TROSY spectra of the protein in different states (apo, +ADP, +Pi, +ADP·Pi).

- Perform sequence-specific assignment of methyl group resonances using a combination of single-point mutagenesis and 3D 13C-resolved [1H,1H]-NOESY experiments.

Setting up the Functional Cycle:

- Prepare the NMR sample containing the assigned protein, ATP, and an ATP regeneration system (e.g., creatine kinase and phosphocreatine) to maintain a constant [ATP].

- Include a phosphate-scavenging system (e.g., Puridine Nucleoside Phosphorylase and 7-methylguanosine) to control phosphate concentration.

Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Record a time series of NMR spectra to monitor the conformational states of the protein during the functional cycle.

- Analyze the signal intensities of reporter residues that are sensitive to nucleotide state.

- Fit the kinetic data to a mathematical model of the cycle to determine the rates of individual steps, including ATP binding, hydrolysis, and product release via parallel pathways.

The GroEL/GroES Chaperonin System

Structural Architecture and Folding Cycle

The GroEL/GroES complex is a large, cylindrical molecular machine that provides a physical compartment for protein folding. Unlike the more versatile Hsp70, GroEL/GroES specializes in assisting a subset of proteins that are prone to aggregation and cannot fold efficiently in the crowded cellular environment [23].

Its core structure consists of:

- GroEL: A double-ring complex of 14 identical 57 kDa subunits, with each ring forming a central cavity. Each subunit has three domains: an Equatorial Domain (contains ATPase site and provides ring-ring contacts), an Intermediate Domain (acts as a hinge), and an Apical Domain (binds substrate and GroES) [22] [23].

- GroES: A single heptameric ring that acts as a "lid" for the GroEL folding chamber [23].

The chaperonin folding cycle is a sophisticated process of coordinated conformational changes, as depicted below:

The cycle begins with a substrate protein (SP) binding to the hydrophobic apical domains of an open GroEL ring (the "cis" ring). ATP binding to the cis ring triggers a series of conformational changes that elevate and twist the apical domains, weakening their affinity for the substrate and priming the ring for GroES binding [23]. GroES binding encapsulates the substrate within a now hydrophilic folding cage, the "Anfinsen cage" [23]. The substrate has a finite time (the lifetime of the GroES complex, ~10-15 seconds) to fold in isolation. ATP hydrolysis in the cis ring and subsequent ATP binding to the opposite ("trans") ring triggers the release of GroES, ADP, and the folded (or folding-committed) protein, resetting the ring for a new cycle [26] [23].

Key Structural Insights and Functional Models

Recent cryo-EM studies have revealed novel conformational states of the GroEL/GroES complex. A 2021 study resolved a bullet-shaped GroEL–GroES1 complex at 3.4 Å resolution, which contained nucleotides in both rings, contrary to the classical model where only the cis ring is occupied [22]. This structure, observed at low ATP:ADP ratios, suggests a new intermediate in the functional cycle and highlights the dynamic nature of the machine [22].

The mechanism by which the chaperonin cage assists folding is still refined, with three primary models under consideration:

Table 2: Models of GroEL/GroES-Assisted Protein Folding

| Model | Core Principle | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Passive Cage (Anfinsen Cage) | The cage passively prevents aggregation by isolating a single molecule, allowing it to fold as in infinite dilution. | Folding rates and pathways inside the cage are identical to those in highly diluted solution for some proteins [23]. |

| Active Cage | The cage actively promotes folding by exerting steric confinement and/or periodic, forced unfolding of trapped non-native states. | GroEL/GroES accelerates the folding of some proteins beyond the rate seen in free dilution [23]. |

| Iterative Annealing | The chaperonin uses ATP-driven cycles of binding and partial unfolding to disrupt kinetically trapped folding intermediates. | GroEL can unfold misfolded states, giving the substrate multiple chances to find the productive folding path [23]. |

These models are not mutually exclusive, and the dominant mechanism may depend on the specific substrate protein.

Comparative Analysis and Research Applications

Functional Distinctions and Collaborations

While both systems are ATP-dependent, Hsp70 and GroEL/GroES have distinct roles and mechanisms. Hsp70 acts as a versatile "clamp" on short hydrophobic stretches, making it ideal for binding a wide array of non-native proteins at various stages of their life cycle [20]. In contrast, GroEL/GroES provides a specialized "cage" for a smaller subset of proteins (in E. coli, ~5-10% of the proteome) that are aggregation-prone and often have complex α/β domains like the TIM-barrel fold [23]. In vivo, these systems often function cooperatively; for instance, some proteins are first handled by the Hsp70 system and subsequently passed to GroEL for final folding [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and their applications for studying these chaperone systems, based on the cited experimental methodologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chaperone Studies

| Reagent / Method | Chaperone System | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope-labeled Chaperones (e.g., Ile/Val/Met 13C1H-methyl labeled) | Hsp70 / GroEL | Enables high-sensitivity NMR studies (e.g., methyl-TROSY) of structure and dynamics in large complexes [24]. |

| ATP Regeneration System (Creatine Kinase/Phosphocreatine) | Hsp70 / GroEL | Maintains constant [ATP] in ATPase assays and functional studies over extended time courses [24]. |

| Phosphate Scavenging System (PNP/7-methylguanosine) | Hsp70 | Controls inorganic phosphate (Pi) concentration, crucial for dissecting hydrolysis and product release steps [24]. |

| Non-hydrolyzable ATP Analogs (e.g., ATPγS) | Hsp70 / GroEL | Traps chaperones in specific conformational states (e.g., Hsp70-ATP state) for structural and functional characterization [26]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | GroEL/GroES | Visualizes high-resolution structures of different conformational states (e.g., bullet-shaped, football-shaped complexes) in the functional cycle [22]. |

The Hsp70 and GroEL/GroES systems represent two elegant but fundamentally different evolutionary solutions to the problem of protein folding in the cell. The Hsp70 system operates through a dynamic ATP-controlled clamping mechanism on short hydrophobic peptides, granting it remarkable versatility in diverse folding tasks [20] [21]. The GroEL/GroES system provides a sequestered nano-cage, leveraging controlled encapsulation to prevent aggregation and actively assist the folding of a more specialized clientele [23]. A deep understanding of their distinct mechanisms, kinetics, and collaborative functions is not only a pursuit of basic science but also a critical foundation for biomedical applications. Given the direct links between chaperone dysfunction and neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and aging [20] [27] [19], these machines represent compelling therapeutic targets. Future research, powered by the advanced experimental tools outlined herein, will continue to unravel the intricacies of these folding machines and pave the way for novel chaperone-targeted therapeutics.

Cellular protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, is a cornerstone of cellular health and functionality. It describes the delicate balance between protein synthesis, folding, modification, trafficking, and degradation, ensuring a stable and functional proteome [19]. The proper folding and function of proteins are paramount, as their three-dimensional conformation directly determines their activity. Maintaining this precise structural integrity is a continuous challenge faced by all cellular compartments. This review provides a comprehensive technical examination of the specialized protein quality control (PQC) systems operating in the cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and mitochondria. We explore the distinct molecular mechanisms, key chaperone players, and experimental approaches that define PQC in each compartment, framing this discussion within the broader context of molecular chaperone research and its implications for understanding and treating human disease.

Endoplasmic Reticulum Chaperone Networks

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a major site for the folding and maturation of secretory and membrane proteins. A network of molecular chaperones and folding enzymes ensures the fidelity of these processes, a system collectively known as ER quality control (ERQC) [28].

The PDIA6 Multichaperone Condensate

A groundbreaking 2025 study revealed that the ER chaperone PDIA6 (Protein Disulfide Isomerase A6) forms a phase-separated condensate that serves as a central organizing hub for the early folding machinery [29]. These condensates are scaffolded by PDIA6 and recruit other essential chaperones, including Hsp70 BiP, the J-domain protein ERdj3, disulfide isomerase PDIA1, and Hsp90 Grp94, thereby enhancing the folding of client proteins like proinsulin and preventing misfolding [29].

- Regulation by Calcium and ER Stress: The formation of PDIA6 condensates is exquisitely regulated by the luminal Ca²⁺ concentration. They form under homeostatic conditions ([Ca²⁺]~800 μM) and dissolve upon ER stress when Ca²⁺ levels drop ([Ca²⁺]~100 μM) [29]. The condensates dissolve in response to ER stress inducers such as tunicamycin, thapsigargin, and cyclopiazonic acid, with dissolution kinetics that correlate with the drug's mechanism of action [29].

- Structural Basis: PDIA6 consists of two catalytically active thioredoxin-like domains (a0 and a) and an inactive domain (b). The protein forms a stable dimer via helix α4 in its a0 domain, a feature distinguishing it from other monomeric PDI family members [29]. The C-terminal tail of PDIA6 is disordered and, along with two other sites at the a-b domain interface, constitutes three distinct Ca²⁺-binding sites that mediate phase separation [29].

The Unfolded Protein Response (UPR)

When the protein-folding load exceeds the capacity of the ERQC system, the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) is activated to remodel the ERQC and restore proteostasis. In mammals, the UPR comprises three signaling pathways regulated by IRE1, ATF6, and PERK, which adapt the ERQC to match diverse physiological and pathological demands [28].

Table 1: Key Chaperones and Enzymes in the Endoplasmic Reticulum

| Chaperone/Enzyme | Function | Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| PDIA6 | Scaffolds multichaperone condensates; disulfide isomerization | Ca²⁺-dependent phase separation; essential gene |

| BiP (Hsp70) | ATP-dependent folding; prevents aggregation | Regulated by co-chaperone ERdj3 and nucleotide exchange |

| Grp94 (Hsp90) | Late-stage folding of specific client proteins | Part of PDIA6 condensate; ATPase cycle |

| PDIA1 | Disulfide bond oxidation, reduction, and isomerization | Recruited to PDIA6 condensates |

| ERdj3 | J-domain co-chaperone that stimulates BiP ATPase activity | Recruited to PDIA6 condensates |

Experimental Analysis of ER Chaperone Condensates

Methodology for Studying PDIA6 Condensates In Vivo and In Vitro [29]:

- Live-Cell Imaging and FRAP: Endogenous or overexpressed PDIA6 is visualized in knock-in cell lines (e.g., HeLa, HEK, U2OS). Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) is used to assess dynamics (e.g., half-life of recovery ~78 seconds), confirming liquid-like properties.

- ER Stress Induction: Cells are treated with pharmacological agents:

- Tunicamycin (1-6 hr treatment): Inhibits N-glycosylation, causing delayed Ca²⁺ depletion and condensate dissolution.

- Thapsigargin/Cyclopiazonic Acid (1 hr treatment): Inhibits SERCA pumps, causing rapid Ca²⁺ depletion and condensate dissolution.

- In Vitro Reconstitution:

- Purified Protein: Recombinant PDIA6 is purified.

- Droplet Formation Buffer: Mimics homeostatic ER conditions with high Ca²⁺ (>500 μM), reducing agents, physiological pH, and a molecular crowding agent.

- Droplet Characterization: Fusion events, growth, and FRAP (half-life ~47 seconds) are quantified to confirm phase separation.

Figure 1: Regulation of PDIA6 Condensates and the ER Stress Response. During homeostasis, high Ca²⁺ promotes PDIA6 dimerization and condensate formation, enhancing client protein folding. ER stress depletes Ca²⁺, dissolving condensates and activating the UPR.

Cytosolic Chaperone Networks

The cytosol faces the formidable challenge of folding a vast and diverse proteome in a molecularly crowded environment. The cytosolic PQC system relies on a sophisticated network of chaperones that guide newly synthesized polypeptides toward their native structures and prevent aggregation [30].

Key Chaperone Systems and Mechanisms

The core cytosolic chaperones can be categorized based on their mechanism and ATP dependence.

- Hsp70 System (ATP-dependent): The Hsp70 system (e.g., bacterial DnaK) is a central foldase. It functions with co-chaperones Hsp40 (DnaJ) and nucleotide exchange factors (GrpE). Hsp70 cycles between ATP-bound (open, low-affinity) and ADP-bound (closed, high-affinity) states to bind and release hydrophobic stretches of unfolded polypeptides, preventing aggregation and promoting folding [30]. Recent evidence suggests Hsp70 is allosterically regulated by proline isomerization at a conserved residue (Pro143) [30].

- Chaperonins (ATP-dependent): The GroEL-GroES system provides an Anfinsen cage—an encapsulated environment that allows proteins to fold in isolation, shielded from the crowded cytosol. This system typically assists proteins that have failed to reach their native state via the Hsp70 system [30].

- Hsp90 System (ATP-dependent): Hsp90 acts as a late-stage folding enhancer for a specific set of client proteins, including steroid hormone receptors and kinases. It interfaces with Hsp70 via co-chaperones like Hop (Hsp70/Hsp90-organizing protein) to facilitate client maturation [30].

- Small Heat-Shock Proteins (sHsps, ATP-independent): sHsps function as holdases, serving as a first line of defense against protein misfolding. They bind to and stabilize unfolding proteins during stress, preventing aggregation. Subsequent refolding requires ATP-dependent chaperones like Hsp70 [30].

- Peptidyl Prolyl Isomerases (PPIases): Proline isomerization is a common rate-limiting step in protein folding. PPIases (e.g., cyclophilins, FKBPs) catalyze the cis/trans isomerization of prolyl bonds, accelerating folding. They also function as co-chaperones by interacting with major chaperone systems like Hsp90 [30].

Table 2: Major Chaperone Systems in the Cytosol

| Chaperone System | Class | Key Components | Proposed Mechanism(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp70 | Foldase (ATP-dep) | Hsp70 (DnaK), Hsp40 (DnaJ), NEF (GrpE) | Iterative substrate binding/release; prevents aggregation |

| Chaperonin | Foldase (ATP-dep) | GroEL, GroES | Anfinsen cage; encapsulation |

| Hsp90 | Foldase (ATP-dep) | Hsp90, co-chaperones (Hop, p23) | Late-stage folding of specific clients |

| Small HSPs | Holdase (ATP-indep) | Various sHsps (e.g., Hsp27) | Prevent aggregation; require Hsp70 for refolding |

| PPIases | Enzyme | Cyclophilins, FKBPs | Catalyze proline isomerization; co-chaperone activity |

Experimental Workflow for Analyzing Chaperone Function

Methodology for Studying ATP-Dependent Chaperone Mechanisms [30]:

- ATPase Activity Assays:

- Purpose: Measure the hydrolysis of ATP to ADP, a key energy input for foldases.

- Protocol: Use purified chaperone (e.g., Hsp70, Hsp90) in reaction buffer with ATP. The reaction is stopped at time points, and ADP production is quantified (e.g., via malachite green assay or HPLC).

- Client Refolding Assays:

- Purpose: Monitor the chaperone's ability to refold denatured client proteins.

- Protocol: A client protein (e.g., Luciferase) is chemically denatured. Refolding is initiated by diluting the denaturant in the presence of the chaperone system, ATP, and an ATP-regenerating system. Recovery of client activity is measured over time.

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis:

- Purpose: Probe the functional role of specific residues (e.g., Hsp70 Pro143).

- Protocol: Mutate the target residue, purify the mutant protein, and compare its ATPase kinetics, conformational stability, and client-refolding efficiency to the wild-type protein.

Figure 2: The Cytosolic Protein Folding Pathway. Nascent polypeptides are assisted by a network of chaperones. The Hsp70 system and PPIases handle initial folding, while recalcitrant proteins are passed to chaperonins or the Hsp90 system. sHsps provide a stress-induced safety net.

Mitochondrial Chaperone Networks

Mitochondria possess their own sophisticated protein quality control (MQC) system to maintain the health of the organelle's proteome, which is essential for its roles in energy production and signaling [31]. This system governs protein import, folding, and degradation.

Protein Import and Intramitochondrial Folding

Nearly all mitochondrial proteins are synthesized on cytosolic ribosomes and must be imported. A 2025 study using selective ribosome profiling revealed that ~20% of mitochondrial proteins in human cells are imported cotranslationally [32]. This pathway prioritizes large, multi-domain proteins with complex topology and is initiated only after a large globular domain emerges from the ribosome, contrasting with ER targeting [32].

Once inside, proteins are folded by resident chaperones. The mitochondrial Hsp70 (mtHsp70) is crucial for importing proteins into the matrix and their subsequent folding, functioning with its co-chaperones [31]. Other chaperones, including Hsp60 and Hsp10, provide a folding cage in the matrix analogous to the GroEL/GroES system in the cytosol [33].

Mitochondrial Dynamics and Proteolysis

MQC extends beyond molecular chaperones to include dynamic remodeling of the entire organelle and targeted degradation of damaged components.

- Mitochondrial Dynamics: Mitochondrial fusion promotes functional complementation between damaged mitochondria by mixing their contents, while fission enables the separation of damaged components for removal [33]. These processes are regulated by dynamin-family GTPases: MFN1/2 and OPA1 mediate fusion, while DRP1 is recruited to execute fission [33].

- Proteolytic Systems: Mitochondria contain intrinsic AAA+ proteases (e.g., Lon, m-AAA, i-AAA) that degrade misfolded or damaged proteins within the organelle, maintaining protein homeostasis [31] [33].

- Mitophagy: When damage is too extensive, entire mitochondria are targeted for degradation via mitophagy, a specialized form of autophagy. This is a key endpoint of the MQC system [33].

Table 3: Core Components of Mitochondrial Quality Control

| MQC Component | Key Molecules | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Import | TOM Complex, TIM Complex | Import of cytosolic proteins |

| Chaperones | mtHsp70, Hsp60/Hsp10 | Protein folding & assembly in matrix |

| Proteases | Lon, m-AAA, i-AAA | Degradation of misfolded proteins |

| Fusion | MFN1, MFN2 (OMM), OPA1 (IMM) | Mixing contents; complementation |

| Fission | DRP1, Mff, MiD49/51 | Isolation of damaged components |

| Clearance | PINK1, Parkin, Mitophagy Receptors | Degradation of damaged mitochondria |

Experimental Approaches to MQC

Methodology for Studying Mitochondrial Quality Control [33]:

- Analysis of Mitochondrial Dynamics:

- Live-Cell Imaging: Cells are transfected with fluorescent markers targeted to mitochondria (e.g., MitoTracker, mito-GFP).

- Quantification: Time-lapse imaging is used to track fission and fusion events. Network morphology is quantified; fragmented networks suggest elevated fission or impaired fusion.

- Assessment of Membrane Potential:

- Purpose: The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is a key indicator of health.

- Protocol: Cells are stained with potentiometric dyes (e.g., TMRE, JC-1) and analyzed by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy. Loss of ΔΨm indicates dysfunction.

- Monitoring Mitophagy:

- Protocol: Use of the pH-sensitive fluorescent tag mt-Keima. Its emission spectrum changes upon delivery to acidic lysosomes, allowing quantification of mitophagic flux via confocal microscopy or flow cytometry.

Figure 3: The Mitochondrial Quality Control System. MQC operates at multiple levels. Chaperones and proteases handle molecular-level damage. Organelle-level stress triggers fusion for repair or fission to isolate damage, targeting severely damaged components for degradation via mitophagy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Protein Quality Control Research

| Reagent / Tool | Application / Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Tunicamycin | Inhibits N-linked glycosylation; induces ER stress. | Dissolution of PDIA6 condensates after 6h treatment [29]. |

| Thapsigargin | Inhibits SERCA pump; depletes ER Ca²⁺ stores. | Rapid dissolution of PDIA6 condensates within 1h [29]. |

| MitoTracker Dyes | Cell-permeable fluorescent probes for labeling mitochondria. | Live-cell imaging of mitochondrial morphology and dynamics [33]. |

| Mdivi-1 | Selective inhibitor of the mitochondrial fission protein DRP1. | To probe the role of fission in mitochondrial network fragmentation [33]. |

| Hsp70 Inhibitors (e.g., VER-155008) | ATP-competitive inhibitors of Hsp70. | To assess Hsp70 dependency in client protein folding assays [30]. |

| mt-Keima | pH-sensitive fluorescent protein for monitoring mitophagy. | Quantification of mitophagic flux via flow cytometry/confocal microscopy [33]. |

| Recombinant PDIA6 | Purified protein for in vitro reconstitution studies. | Forming condensates in droplet formation buffer to study phase separation mechanics [29]. |

Concluding Perspectives

The chaperone networks within the ER, cytosol, and mitochondria, while specialized for their unique environments, collectively form an integrated cellular defense system against proteotoxic stress. The recent discovery of regulated biomolecular condensates in the ER exemplifies how the spatial organization of chaperones adds a new layer of regulation to protein folding homeostasis [29]. Ongoing research continues to elucidate the complex interplay between these compartments and how their failure contributes to disease. Understanding these mechanisms at a granular level, as outlined in this technical guide, provides a foundation for developing therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating proteostasis networks to treat neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and metabolic disorders.

Molecular chaperones constitute an essential network of proteins responsible for maintaining cellular proteostasis (protein homeostasis). They function by interacting with, stabilizing, and assisting other proteins in acquiring their functionally competent conformations, thereby preventing aggregation, premature folding, or misfolding [34]. The journey of a protein, from its emergence as a nascent chain from the ribosome to its eventual degradation, is fraught with risks of misfolding and aggregation, particularly in the crowded cellular environment. Molecular chaperones act as guardians throughout this lifecycle, ensuring proteome integrity and functionality [19] [35].

This review delineates the core mechanistic activities of molecular chaperones—folding assistance, holdase function, and disaggregase action—framing them within the critical context of protein quality control (PQC). The precise execution of these roles is fundamental to cellular health, and their dysregulation is a hallmark of numerous human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders and cancer [19] [6] [36]. By exploring the structures, mechanisms, and functional classes of chaperones, this guide provides a comprehensive technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals working at the forefront of proteostasis research.

Chaperone-Assisted Protein Folding: From Nascent Chains to Native Structures

The process of protein folding, whereby a linear polypeptide chain attains its intricate three-dimensional structure, is one of the most fundamental in cell biology. While the amino acid sequence inherently encodes the native structure, the cellular environment presents challenges such as macromolecular crowding that increase the risk of off-pathway reactions and aggregation [19] [35]. Molecular chaperones mitigate these risks, ensuring efficient and accurate folding.

Folding in the Cytosol: The Hsp70 and Chaperonin Systems

Two major systems work collaboratively in the cytosol to manage the folding of a vast repertoire of client proteins: the Hsp70 system and the chaperonins.

The Hsp70 System (DnaK in E. coli): Hsp70 is a central hub in the cellular chaperone network [35]. It functions as an ATP-dependent molecular machine that binds short, hydrophobic peptide segments of client proteins in a reversible manner. Its activity is regulated by a core mechanism and co-chaperones [37]:

- ATP-Dependent Conformational Cycling: When Hsp70 is bound to ATP, its substrate-binding domain is in an open conformation, characterized by a low affinity for substrates and a high on/off rate. Substrate binding stimulates ATP hydrolysis.

- ADP-Bound State: The hydrolysis of ATP to ADP triggers a conformational change, closing a "lid" over the substrate-binding domain. This results in a high-affinity state that traps the client protein, stabilizing it and preventing aggregation.

- Co-chaperone Regulation: The ATPase cycle is tightly regulated by co-chaperones. Hsp40s (DnaJ) act as targeting factors, recognizing non-native clients and delivering them to Hsp70 while stimulating its ATPase activity. Nucleotide Exchange Factors (NEFs), such as Hsp110 (in eukaryotes) or GrpE (in bacteria), facilitate the release of ADP, allowing ATP to bind and the client to be released for a new cycle of binding or for spontaneous folding [35] [37].

The Chaperonin System (GroEL/GroES in E. coli): For proteins that are prone to aggregation or cannot fold in the crowded cytosol, the chaperonins provide an isolated folding chamber [34]. GroEL is a large, double-ringed complex with 14 subunits. Its mechanism involves:

- Client Capture: An unfolded protein binds to the hydrophobic apical domains of one ring of GroEL.

- Encapsulation: The binding of ATP and the co-chaperonin GroES (a single-ring heptamer) triggers a dramatic conformational change. The GroES "lid" seals the chamber, and the interior lining becomes hydrophilic, creating a privileged environment for folding.

- Folding and Release: The client protein is given time to fold inside this Anfinsen cage. After ATP hydrolysis in the first ring, binding of ATP to the second ring triggers the release of GroES, the client, and ADP. If the protein has not reached its native state, it may undergo another round of binding and encapsulation [34].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these two major folding systems.

Table 1: Core Protein Folding Systems in the Cytosol

| System | Key Components | ATP-Dependent | Core Mechanism | Representative Clients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp70 System | Hsp70 (DnaK), Hsp40 (DnaJ), NEF (GrpE/Hsp110) | Yes | Transient binding and release cycles to prevent aggregation and promote folding [37] [34] | Nascent chains, transcription factors, kinase precursors [6] |

| Chaperonin System (GroEL/ES) | Hsp60 (GroEL), Hsp10 (GroES) | Yes | Encapsulation in an isolated chamber for folding [34] | ~10-15% of cytosolic proteins; large, aggregation-prone proteins [34] |

Folding in Specialized Compartments: The Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the entry point for proteins in the secretory pathway, and it possesses a dedicated set of chaperones for protein maturation [37]. The ER Hsp70, BiP, is a central player that gates the Sec61 translocon, facilitates polypeptide translocation through a ratcheting mechanism, and assists in folding within the ER lumen [37]. Its function is aided by co-chaperones like Lhs1/GRP170, which acts as a NEF. Other critical ER chaperones include the lectins calnexin and calreticulin, which bind to glycoproteins to promote folding and retain immature proteins, and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), which catalyzes the formation and isomerization of disulfide bonds [37].

The following diagram illustrates the ATP-dependent conformational cycle of Hsp70, a core mechanism in chaperone-assisted folding.

Stabilization and Prevention: The Holdase Activity

Not all chaperone functions involve active folding. A critical first line of defense against proteostasis collapse is the holdase activity, a passive, ATP-independent function where chaperones bind to non-native proteins to prevent their aggregation [35] [34]. This activity is crucial during cellular stress, such as heat shock or oxidative stress, when the load of unfolded proteins surges.

Small Heat Shock Proteins (sHSPs) as Canonical Holdases

The small HSPs (sHSPs), such as HSPB1 (Hsp27) and αB-crystallin (HspB5), are archetypal holdases. They form large, dynamic oligomers that act as a molecular "sponge" for unfolding clients [6]. Their structure consists of a conserved α-crystallin domain flanked by variable N- and C-terminal regions. The flexible N-terminal allows them to bind a wide array of destabilized proteins, sequestering them in a soluble, folding-competent state until stress conditions subside and they can be refolded by ATP-dependent chaperones like Hsp70 [6].

SecB: A Specialized Bacterial Holdase for Translocation

In bacteria, SecB is a dedicated holdase that maintains precursor proteins in an unfolded, translocation-competent state for export through the Sec translocon [38]. Structural studies reveal that SecB uses long hydrophobic grooves to bind multiple segments of a client protein, effectively "wrapping" it and conferring strong antifolding activity. This binding mode kinetically traps the protein in an unfolded state, preventing premature folding that would preclude membrane translocation [38].

Table 2: Key Chaperones with Holdase Activity

| Chaperone | Class | ATP-Dependent | Primary Function | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sHSPs (e.g., Hsp27) | Small HSP | No | First-line defense against aggregation during stress [6] [34] | Forms large oligomers; binds diverse clients via flexible N-termini [6] |

| SecB | Specialized Holdase | No | Maintains preprotein unfolding for translocation in bacteria [38] | Uses hydrophobic grooves for multivalent binding, wrapping clients to inhibit folding [38] |

| Hsp33 | Redox Sensor | No | Activated by oxidative stress to prevent aggregation [34] | Functions as a redox-regulated holdase [34] |

Repair and Reactivation: Catalytic Unfoldase and Disaggregase Activities

When prevention fails and misfolded proteins form aggregates, cells deploy a powerful repair machinery: chaperones that function as unfoldases and disaggregases. Unlike holdases, these are ATP-dependent nanomachines that actively disentangle and extract polypeptides from aggregates, giving them a second chance to refold correctly [35].

The Hsp100 Disaggregase System in Yeast

In yeast, the Hsp104 disaggregase is a member of the AAA+ (ATPases Associated with diverse cellular Activities) family. It forms a hexameric ring that threads aggregated proteins through its central pore, using the energy of ATP hydrolysis to mechanically pull and unfold the trapped polypeptides [34]. This activity is essential for yeast prion propagation and thermotolerance.

The Collaborative Hsp70-Based Disaggregase System

In metazoans, a collaborative system centered on Hsp70 performs disaggregation. This system involves a partnership between Hsp70 (DnaK), Hsp40 (DnaJ), and Hsp110 (in eukaryotes, or GrpE in bacteria). Hsp110/GrpE acts as a potent NEF for Hsp70, and recent studies show that Hsp110 synergizes with Hsp70 to drive the catalytic disaggregation of even stable amyloid fibrils, such as those formed by α-synuclein, which is linked to Parkinson's disease [35]. The mechanism involves iterative cycles of binding, unfolding/pulling, and release, transforming aggregated or misfolded substrates into transiently unfolded intermediates capable of spontaneous refolding [35].

The following diagram outlines the collaborative mechanism of the Hsp70-based disaggregase system.

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies for Studying Chaperone Function

Understanding chaperone mechanisms requires a multidisciplinary toolkit that probes structure, dynamics, and function. The following protocols summarize key methodologies cited in the literature.

Structural Analysis of Chaperone-Substrate Complexes

Protocol: Solution NMR for Chaperone-Client Complexes

- Objective: Determine the structure and dynamics of a chaperone bound to an unfolded client protein at atomic resolution.

- Method Summary (as applied to SecB-unfolded protein complexes) [38]:

- Isotopic Labeling: Produce uniformly (^{15})N- and (^{13})C-labeled chaperone (e.g., SecB) and/or client protein (e.g., alkaline phosphatase, maltose-binding protein) in E. coli.

- Complex Formation: Mix the chaperone with the unfolded client protein under non-denaturing conditions.

- NMR Data Collection: Acquire multidimensional NMR spectra (e.g., (^{1})H-(^{15})N HSQC, TROSY) to observe chemical shift perturbations and intermolecular nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs).

- Structure Calculation: Use experimental restraints (NOEs, residual dipolar couplings, etc.) in computational programs like CYANA or Xplor-NIH to calculate an ensemble of structures representing the complex.

- Key Insight: This approach revealed that SecB uses long hydrophobic grooves to bind multiple segments of the client, causing the protein to wrap around the chaperone and explaining its potent antifolding activity [38].

Functional Assays for Disaggregase Activity

Protocol: Monitoring Amyloid Disaggregation In Vitro

- Objective: Quantify the ability of a chaperone system (e.g., Hsp70/Hsp40/Hsp110) to disassemble pre-formed amyloid fibrils.

- Method Summary (as applied to α-synuclein fibrils) [35]:

- Fibril Formation: Incubate purified α-synuclein with shaking to form mature amyloid fibrils. Confirm fibril formation using Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence, which increases upon binding to cross-β-sheet structures.

- Disaggregation Reaction: Mix the pre-formed fibrils with the chaperone system (Hsp70, Hsp40, Hsp110) in the presence of an ATP-regenerating system.

- Kinetic Monitoring: Monitor the reaction over time by:

- ThT Fluorescence: A decrease signals the loss of amyloid structure.

- Electron Microscopy: Visualize the morphological changes from fibrils to smaller species.

- Native PAGE or Size-Exclusion Chromatography: Assess the appearance of soluble, monomeric α-synuclein.

- Validation of Reactivation: Test the functionality of the disaggregated protein in a relevant biochemical assay.

- Key Insight: This assay demonstrated that the Hsp70/Hsp40/Hsp110 system can catalytically convert rigid α-synuclein amyloids into natively refolded, functional monomers [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The study of chaperone biology relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below details essential materials for experimental research in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Chaperone Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Chaperone Proteins (e.g., Hsp70, Hsp40, GroEL/ES) | Purified components for in vitro folding, holdase, and disaggregation assays. | Reconstituting ATP-dependent refolding of denatured luciferase [35]. |

| ATP-Regenerating System (e.g., Creatine Phosphate & Kinase) | Maintains constant ATP levels in ATP-dependent chaperone assays. | Essential for sustained activity in long-term disaggregation experiments [35]. |

| Thioflavin T (ThT) | Fluorescent dye that binds amyloid fibrils; used to monitor aggregation/disaggregation. | Quantifying the kinetics of α-synuclein fibril formation and chaperone-mediated disassembly [35]. |

| Isotopically Labeled Amino Acids ((^{15})N, (^{13})C) | Production of labeled proteins for structural analysis by NMR spectroscopy. | Determining the solution structure of chaperone-client complexes, like SecB with unfolded proteins [38]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Generate chaperone mutants to dissect functional domains and mechanistic steps. | Creating Hsp70 ATPase domain mutants (e.g., P143A) to study interdomain communication [37]. |

| CHIP Ubiquitin Ligase | Connects chaperone network to protein degradation; ubiquitinates Hsp70-bound clients. | Studying the triage decision between refolding and degradation by the proteasome [39]. |

Decoding the Chaperone Code: Techniques and Research Applications

Molecular chaperones are fundamental components of the cellular machinery, responsible for assisting the folding, assembly, and stabilization of other proteins. Within the crowded cellular environment, both newly synthesized and pre-existing polypeptides are perpetually at risk of misfolding and aggregation. Molecular chaperones counter these threats, thereby maintaining protein homeostasis, a state of proper protein folding and function essential for cellular health [7] [2]. Their role is a cornerstone of protein quality control, a system that surveys individual protein molecules to prevent the uncontrolled aggregation that can lead to devastating diseases [2]. Elucidating the structures of these chaperones and their client complexes is critical for understanding their mechanism of action. This whitepaper delves into the breakthroughs achieved by two key structural biology techniques—X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM)—in unraveling the intricate workings of chaperone complexes.

The Structural Biology Toolkit: Principles and Workflows

The determination of high-resolution structures of chaperone complexes relies on advanced biophysical techniques. The synergistic application of X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM has proven particularly powerful, each with distinct strengths and workflows.

X-ray Crystallography

This traditional high-resolution method involves purifying the protein or complex and growing it into a highly ordered crystal. When exposed to an X-ray beam, the crystal diffracts the radiation, producing a pattern used to calculate an electron density map and an atomic model.

Single-Particle Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM)

Cryo-EM has emerged as a revolutionary technique for studying macromolecular structures. It involves freezing purified protein complexes in a thin layer of vitreous ice, preserving their native state. An electron microscope is then used to capture thousands of 2D images of individual particles at random orientations. Computational algorithms align, classify, and average these images to reconstruct a high-resolution 3D structure [40].

Diagram 1: Generalized workflow for single-particle cryo-EM analysis.

Deciphering Chaperone Mechanisms Through Integrated Structural Biology

The combination of X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM has been instrumental in revealing the mechanisms of chaperone systems. Crystallography often provides the first atomic-level details of individual components or sub-complexes, while cryo-EM allows for the visualization of larger, more flexible functional assemblies.

The Chaperonin CCT and mTOR Complex Assembly

The eukaryotic chaperonin CCT (also known as TRiC) is a multi-subunit, ATP-dependent folding machine that plays a critical role in folding proteins with complex topologies, such as β-propeller domains. A landmark study combined functional assays with high-resolution (4.0 Å) cryo-EM to investigate CCT's role in assembling the mTORC1 complex, a master regulator of cell growth [41].

The cryo-EM structure of a human mLST8-CCT intermediate, isolated directly from cells, revealed mLST8—a β-propeller protein—in a near-native state bound deep within the CCT folding chamber. The structure showed that mLST8 interacts mainly with the disordered N- and C-termini of specific CCT subunits in both rings, identifying a distinct binding mode different from other β-propeller substrates like Gβ [41]. This work demonstrated that CCT is essential for the folding of mLST8 and Raptor, another β-propeller component of mTORC1, thereby directly linking chaperone function to the assembly of a critical signaling complex.

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Chaperone-Substrate Interactions by Cryo-EM

- Construct Design: Express substrate protein (e.g., mLST8) with an affinity tag in a suitable cell line.

- Complex Isolation: Use co-immunoprecipitation with antibodies against the substrate or a chaperone subunit (e.g., CCT5) to pull down endogenous chaperone-substrate complexes from cell lysates.

- ATP-dependent Release Assay: Incubate immunopurified complexes with ATP (e.g., 5 mM) and measure the amount of substrate remaining bound over time to confirm a dynamic folding interaction.

- Sample Vitrification: Apply the purified complex to an EM grid, blot away excess liquid, and rapidly freeze in liquid ethane to form vitreous ice.

- Data Collection & Processing: Acquire thousands of micrographs using a cryo-electron microscope. Perform particle picking, 2D classification, and 3D reconstruction to generate the final density map.

- Model Building: Fit or build an atomic model into the cryo-EM density map for structural analysis [41].

The Donor Strand Exchange Mechanism in Pilus Biogenesis

The chaperone-usher (CU) pathway in bacteria is a superb example of how combined structural biology can unravel a complex assembly line. This pathway, which builds hair-like pili on the bacterial surface, involves a periplasmic chaperone and an outer membrane usher protein. X-ray crystallography of individual chaperone-subunit complexes revealed a groundbreaking mechanism known as donor strand complementation (DSC) [40].