Hsp70 and Hsp60 Chaperone Mechanisms: Orchestrating Proteostasis in Health and Disease

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the structural and functional mechanisms of Hsp70 and Hsp60 molecular chaperones in maintaining cellular proteostasis.

Hsp70 and Hsp60 Chaperone Mechanisms: Orchestrating Proteostasis in Health and Disease

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the structural and functional mechanisms of Hsp70 and Hsp60 molecular chaperones in maintaining cellular proteostasis. We explore the foundational biology of these chaperone systems, including their ATP-dependent allosteric regulation and complex cooperation with co-chaperones. The review examines cutting-edge methodological approaches for investigating chaperone functions and discusses the direct implications of chaperone dysregulation in human pathologies, including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. A significant focus is placed on emerging therapeutic strategies that target these chaperone networks, highlighting small-molecule inhibitors and innovative drug design approaches currently in development. This synthesis of mechanistic insights and translational applications offers researchers and drug development professionals a strategic framework for advancing chaperone-targeted therapeutics.

Structural Biology and Core Mechanisms of Hsp70 and Hsp60 Chaperone Systems

Evolutionary Conservation and Genomic Organization of Chaperone Families

Molecular chaperones, including the highly conserved Hsp70 and Hsp60 families, constitute fundamental components of the cellular protein homeostasis (proteostasis) network. These proteins facilitate nascent polypeptide folding, prevent protein aggregation, mediate intracellular trafficking, and support stress response pathways. The evolutionary conservation and genomic organization of these chaperone families reflect their critical role in maintaining cellular viability under both normal and stress conditions. Understanding their structural and genomic features provides crucial insights for developing therapeutic interventions for protein misfolding diseases, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders. This review examines the evolutionary trajectories, structural conservation, and genomic architecture of Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone families within the broader context of proteostasis research.

Structural Conservation and Evolutionary Relationships

Hsp60 Chaperonin Family

The Hsp60 family, also known as chaperonin 60 (Cpn60), demonstrates remarkable evolutionary conservation from prokaryotes to eukaryotes. In prokaryotes such as Escherichia coli, Hsp60 functions as the GroEL/GroES complex, forming a double-ring barrel structure that facilitates protein folding within a central cavity [1]. This complex captures non-native substrate proteins through hydrophobic interactions and encloses them in the central ring cavity where folding occurs protected from aggregation [1].

Eukaryotic Hsp60 localizes primarily to mitochondria (80-85%) with the remainder (15-20%) found in the cytoplasm [1]. The protein forms a double-ring assembly with each subunit approximately 60 kDa, functioning as a molecular chaperone for naïve polypeptides and unfolded proteins in both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial compartments [1]. The table below summarizes the key classification and characteristics of chaperonin families:

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Chaperonin Families

| Group | Chaperonins | Organisms | Localization | Structural Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | GroEL/GroES, HSP60/HSP10, Cpn60, HSPD1/E | Prokaryotes, Eukaryotes | Cytoplasm, Mitochondria, Nucleus, Chloroplast | Homo-oligomeric, GroES/HSP10-dependent, seven subunits per ring |

| Group II | TRiC/CCT, TCP1 | Archaea, Eukaryotes cytosol | Cytosol | Hetero-oligomeric, GroES/HSP10-independent, eight to nine subunits per ring |

Structural studies reveal that Hsp60 monomers consist of three distinct domains: an apical domain forming the barrel, an intermediate domain connecting the other domains, and an equatorial domain at the base of the ring [1]. The binding and hydrolysis of ATP triggers conformational changes that facilitate substrate protein folding and release. Under pathological conditions, increased Hsp60 can exhibit either pro-survival or lethal functions depending on whether it exists in monomeric or oligomeric forms [1].

Hsp70 Chaperone Family

The Hsp70 family represents one of the most evolutionarily conserved chaperone systems across species. These proteins contain three main domains: an N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain (NBD), a substrate-binding domain (SBD), and a C-terminal substrate-binding region [2]. The NBD exhibits ATPase activity that regulates substrate binding and release cycles, while the SBD interacts with client proteins through hydrophobic interactions.

Hsp70 proteins localize to various cellular compartments including cytoplasm, nucleus, mitochondria, chloroplasts, and endoplasmic reticulum [2]. In plants, the Hsp70 multigene family has expanded significantly, with 113 Hsp70 transcription factors identified in hybrid tea rose (Rosa hybrida), classifying into three phylogenetic subfamilies (I, II, and III) [2]. Most members (51 TFs) fall into subfamily II, exhibiting wide gene structural variations among subfamilies [2].

Genomic Organization and Family Expansion

Evolutionary Expansion of Chaperone Families

Chaperone families have undergone significant expansion throughout evolution, reflecting adaptation to increased proteostatic demands in multicellular organisms. The HSP40 family expanded from three members in E. coli and 22 members in budding yeast to 49 members in humans [3]. Similarly, the evolution of the sHSP family shows complex patterns, with plants and some lower eukaryotes possessing more sHSPs than mammals and higher eukaryotes [3].

This expansion has facilitated functional specialization, with different chaperone isoforms acquiring distinct substrate specificities and regulatory mechanisms. While prokaryotes utilize the same chaperones for both de novo protein folding and stress response, unicellular eukaryotes evolved two separately regulated systems—a basal system and a stress-inducible system—composed of distinct members of the same chaperone families [3]. This two-level organization is conserved in multi-cellular eukaryotes but further complicated by tissue-specific requirements.

Genomic Architecture Across Species

The genomic organization of chaperone genes reveals both conserved and species-specific patterns. In Arabidopsis thaliana, 18 HSP70 genes show varied expression across different tissues, developmental stages, and environmental conditions [2]. Rice (Oryza sativa) possesses 32 HSP70 genes, most exhibiting tissue-specificity and sensitivity to environmental stress [2]. Similarly, soybean (Glycine max) contains 61 HSP70 genes involved in tissue development and response to drought and heat stress [2].

Table 2: HSP70 Gene Family Size Across Species

| Organism | HSP70 Gene Count | Tissue Specificity | Stress Responsiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 18 | Varied across tissues | Heat stress responsive |

| Oryza sativa (rice) | 32 | Tissue-specific | Environmental stress sensitive |

| Glycine max (soybean) | 61 | Involved in tissue development | Drought and heat stress responsive |

| Rosa hybrida (tea rose) | 113 | Strong organ specificity | Heat stress responsive |

The hybrid tea rose exemplifies the extensive expansion of HSP70 genes, with 113 identified members showing wide gene structural variations [2]. Group I and II members typically lack introns, while group III members contain 1-4 exons and introns [2]. Promoter analysis of these genes reveals numerous cis-acting elements associated with abiotic stress, hormone response, growth and development, and light response [2].

Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns

Core and Variable Chaperone Networks

Recent transcriptomic analyses across human tissues reveal that the chaperone system is composed of core elements uniformly expressed across tissues and variable elements differentially expressed to meet tissue-specific requirements [3]. Approximately 74% of chaperones are expressed in all human tissues, compared to 47% of other protein-coding genes [3]. Core chaperones are significantly more abundant across tissues and more essential for cell survival than variable chaperones [3].

This layered architecture forms tissue-specific functional networks that are established during development and decline with age [3]. Analysis of human organ development and aging brain transcriptomes reveals that these functional networks are established in development and deteriorate during aging processes [3].

Expression Regulation

Chaperone expression exhibits complex regulation patterns. In hybrid tea rose, gene expression analysis revealed that 57 HSP70 genes displayed strong organ specificity and response to heat stress [2]. Notably, expression levels of RhHSP70-69 and RhHSP70-88 increased significantly after heat stress, suggesting crucial roles in thermotolerance [2]. Subcellular localization confirmed these proteins reside in the nucleus [2].

The quantitative composition of chaperone systems significantly impacts proteostatic capacity. While chaperone overexpression typically enhances folding capacity, specific chaperones when overexpressed can disrupt folding—as demonstrated with FKBP51 overexpression in a tau transgenic mouse model leading to tau accumulation and toxic oligomers [3].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Chaperone Systems

Interaction Mapping Techniques

Advanced proteomic approaches have enabled systematic characterization of chaperone interactions. One comprehensive study combined mass spectrometry and quantitative high-throughput LUMIER assays to map chaperone/co-chaperone/client interaction networks in human cells [4]. This approach identified hundreds of novel chaperone clients and delineated their participation in specific co-chaperone complexes.

The LUMIER method involves stably expressing prey proteins fused to Renilla luciferase in 293T cells. Putative interactors (baits) are tagged with a 3xFLAG epitope and transfected into the reporter cell line. Cell lysates are incubated on anti-FLAG coated plates, and interactions are quantified via luminescence detection [4]. This method enables quantitative assessment of protein-protein interactions with high sensitivity.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Chaperone Interaction Mapping. This diagram illustrates the integrated approach combining affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) and LUMIER assays for systematic characterization of chaperone complexes.

Phylogenetic and Genomic Analysis Methods

Phylogenetic analysis of chaperone families typically involves multiple sequence alignment and construction of evolutionary trees using neighbor-joining or maximum likelihood methods. For example, analysis of rose HSP70 genes utilized MEGA7 software with 1000 bootstrap replicates to establish reliable phylogenetic relationships [2].

Genome-wide identification employs tools such as TBtools for preliminary screening, Pfam database searches using hidden Markov models (HMMs), and SMART and NCBI CDD for domain identification [2]. Promoter analysis typically examines 2000 bp upstream of the start codon using platforms like PlantCARE to identify cis-acting elements [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chaperone Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| 3xFLAG-V5 Epitope Tags | Protein interaction studies | Enables affinity purification and identification of chaperone complexes |

| Renilla Luciferase | LUMIER assays | Quantitative measurement of protein-protein interactions |

| SAINT Algorithm | Mass spectrometry data analysis | Statistical framework for identifying high-confidence interactors |

| HMMER/Pfam Databases | Gene family identification | Identification of conserved chaperone domains in genomic sequences |

| TPR Domain Constructs | Co-chaperone studies | Investigation of Hsp90 and Hsp70 interaction mechanisms |

| CDC37 Constructs | Kinase chaperone studies | Specific analysis of kinase folding and maturation pathways |

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The evolutionary conservation of chaperone families makes them attractive therapeutic targets. The structured organization into core and variable components across tissues provides opportunities for tissue-specific therapeutic interventions [3]. Understanding the precise mechanisms of Hsp70 and Hsp60 in protein folding offers potential for treating conformational diseases like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Huntington's, and ALS [5].

Current therapeutic strategies targeting chaperones have evolved through four developmental stages: (1) pan-isoform inhibitors (1990s), (2) isoform-selective inhibitors (2000s), (3) protein-protein interaction disruptors (2010s), and (4) multi-specific molecules (2020s) [6]. These approaches leverage the extensive structural and mechanistic knowledge of chaperone systems to develop targeted therapeutics.

The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone families exhibit remarkable evolutionary conservation while demonstrating adaptive expansion and specialization across species. Their genomic organization reflects a balance between conserved core functions and tissue-specific adaptations essential for maintaining proteostasis. Integrated experimental approaches combining proteomics, genomics, and structural biology continue to unravel the complexity of chaperone networks. This knowledge provides the foundation for developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting the proteostasis network in human disease, particularly in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and aging-related conditions.

Molecular chaperones are fundamental components of the cellular proteostasis network, with Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperones representing two paradigmatic systems that utilize distinct mechanistic strategies. Hsp70 employs a bidirectional allosteric mechanism between its nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and substrate-binding domain (SBD) to interact with client proteins, whereas Hsp60 forms complex double-ring oligomeric structures that provide a protected folding chamber. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of their domain architectures, allosteric regulation, and oligomerization dynamics, synthesizing recent structural and biochemical advances. The information is presented to equip researchers and drug development professionals with refined mechanistic understanding and methodological approaches for investigating these critical chaperone systems, with implications for therapeutic intervention in protein aggregation diseases.

Protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, relies on an integrated network of molecular chaperones that prevent aggregation, facilitate folding, and mediate remodeling of client proteins. The Hsp70 and Hsp60 families represent two essential, yet mechanistically distinct, chaperone systems. Hsp70 functions as a central hub in proteostasis through transient binding to short hydrophobic client segments, with its activity governed by an allosteric interplay between its NBD and SBD [7] [8]. In contrast, Hsp60 forms elaborate double-ring complexes that encapsulate clients within an isolated folding chamber, providing a protected environment for folding to occur [9] [10]. While both systems are ATP-dependent, their architectural principles and operational mechanisms differ significantly. Understanding their distinct domain organizations and functional regulations provides critical insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies against proteostasis-related pathologies, including neurodegenerative diseases and cancer.

Hsp70: NBD-SBD Allosteric Communication

Domain Organization and Structural Basis

The Hsp70 chaperone consists of two principal domains: an N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) of approximately 45 kDa and a C-terminal substrate-binding domain (SBD) of about 25 kDa [7] [11]. The NBD adopts an actin-like fold composed of four subdomains (IA, IB, IIA, IIB) arranged in two lobes that form a deep cleft for nucleotide binding [7]. The SBD is further divided into a β-sandwich subdomain (SBDβ) containing the substrate-binding groove and an α-helical lid subdomain (SBDα) [7] [8]. These domains are connected by a conserved, hydrophobic interdomain linker that serves as a critical structural element for allosteric coupling [7].

Table 1: Key Structural Elements in Hsp70 Allostery

| Structural Element | Domain Location | Functional Role | Conserved Residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interdomain linker | Connects NBD & SBD | Transmits allosteric signals | VLLL (in E. coli DnaK) |

| Nucleotide-binding cleft | NBD | Binds ATP/ADP; regulates conformation | Present in all four subdomains |

| Substrate-binding groove | SBDβ | Binds hydrophobic client sequences | Loops L1,2, L3,4, L4,5, L5,6 |

| α-helical lid | SBDα | Controls substrate access | Helices αA-αE |

| Hydrogen bond network | NBD-SBD interface | Mediates interdomain communication | R151, K155, R167, D481 (DnaK) |

The Allosteric Mechanism

Hsp70 function is governed by a bidirectional allosteric mechanism that couples nucleotide status with substrate-binding affinity:

ATP-bound state: ATP binding to the NBD induces substantial conformational changes, including subdomain re-orientations and rotation of lobe II [7]. This facilitates docking of both SBD subdomains onto the NBD, resulting in an open conformation where the α-lid detaches from the βSBD [7] [11]. This state exhibits low substrate affinity but fast association and dissociation rates, enabling rapid substrate binding and release [8].

ADP-bound state: ATP hydrolysis and ADP binding promote domain undocking, where the NBD and SBD behave as independent dynamic units [7]. The SBD adopts a closed conformation with the α-lid packed against the βSBD, creating a stable interface that results in high substrate affinity and slow substrate exchange rates [7] [11].

Allosteric coupling: The system operates as an energetic "tug-of-war" between two orthogonal interfaces: the βSBD-α-lid interface (favored in ADP-state) and the NBD-SBD interface (favored in ATP-state) [7]. Key residues, including D481 in E. coli DnaK, form a hydrogen bond network that mediates interdomain communication [11]. Substrate binding to the SBD allosterically stimulates ATP hydrolysis at the NBD, completing the bidirectional communication cycle [11] [8].

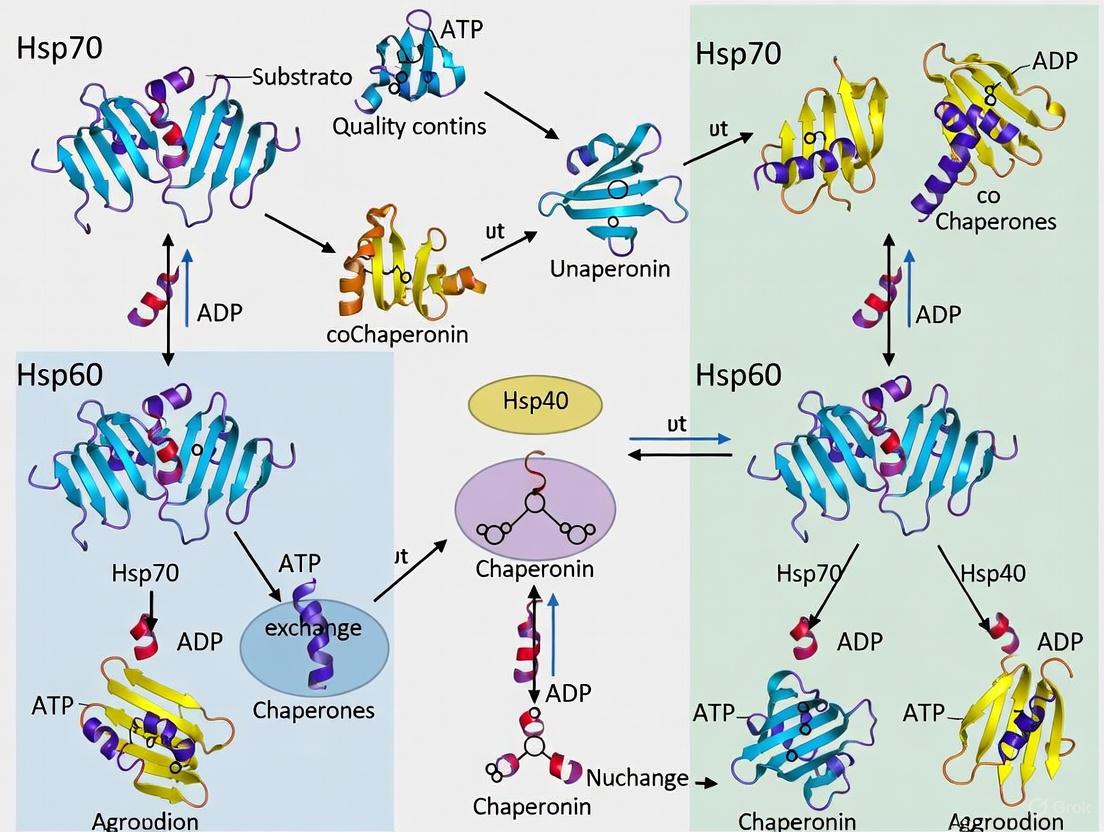

Figure 1: Hsp70 Allosteric Cycle. ATP binding induces a low-affinity, open state; hydrolysis yields a high-affinity, closed state; nucleotide exchange resets the cycle. Substrate binding stimulates ATP hydrolysis, enabling allosteric control.

Key Experimental Approaches and Reagents

Investigating Hsp70 allostery requires specialized methodologies and reagents:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Hsp70 Allostery Studies

| Reagent / Method | Specification / Function | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| DnaK (E. coli Hsp70) | Model Hsp70 for mechanistic studies | Structural and biochemical analyses [7] [11] |

| TNP-ATP / MANT-nucleotides | Fluorescent nucleotide analogs | Monitoring nucleotide binding and kinetics [12] |

| Tryptophan fluorescence (W102) | Intrinsic fluorescence reporter | Detecting ATP-induced conformational changes [11] |

| Allosteric mutants (D481A/K) | Disrupt specific interdomain contacts | Probing allosteric communication pathways [11] |

| Single-turnover ATPase assays | Measures hydrolysis without exchange limitation | Assessing basal and stimulated ATPase rates [11] |

| ITC (Isothermal Titration Calorimetry) | Direct measurement of binding thermodynamics | Determining nucleotide affinity and stoichiometry [12] |

| Proteolysis sensitivity assays | Monitors domain docking/undocking | Probing conformational states under different conditions [12] |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Hsp70 Allosteric Mutants

- Protein Purification: Express and purify wild-type and mutant Hsp70 (e.g., D481A/K) using affinity and size-exclusion chromatography [11].

- Conformational Analysis: Monitor tryptophan fluorescence (W102 in DnaK) with excitation at 295 nm; ATP-induced blueshift indicates successful interdomain communication [11].

- Substrate Binding Kinetics: Use FRET-labeled peptides to measure substrate dissociation rates in presence of ATP versus ADP [11].

- ATPase Activity: Employ quenched-flow instruments for single-turnover ATP hydrolysis measurements; assess stimulation by J-domain proteins and substrates [11].

- Structural Validation: Utilize X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM to determine mutant structures; NMR for analyzing dynamics [7] [11].

Hsp60: Double-Ring Oligomerization and Function

Domain Architecture and Assembly

Mitochondrial Hsp60 (mtHsp60), a Group I chaperonin, shares structural homology with bacterial GroEL but exhibits distinct assembly properties. Each Hsp60 monomer consists of three domains: an equatorial domain that contains the ATP-binding site and mediates ring formation, an apical domain that binds substrates and the co-chaperonin Hsp10, and an intermediate domain that connects them and provides flexibility [9] [13]. Unlike GroEL, which forms stable tetradecamers, mtHsp60 exhibits dynamic oligomerization that depends on nucleotide presence [9] [10].

Table 3: Hsp60 Oligomeric States and Properties

| Oligomeric State | Structural Features | Functional Capacity | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer | Single subunit; disordered interaction interfaces | No ATPase activity; cannot assist folding [10] [13] | Low; prone to aggregation |

| Heptamer (Single-ring) | Seven subunits arranged in a ring; open at one end | Active folding with Hsp10; functional but less efficient than double-ring [9] [10] | Moderate; requires nucleotide for stability |

| Tetradecamer (Double-ring) | Two back-to-back heptameric rings; symmetrical structure | High-efficiency folding machine; encapsulates substrates [9] | High; stabilized by ATP and Hsp10 |

Oligomerization Mechanism and Functional Cycle

Hsp60 assembly and function are governed by nucleotide-dependent conformational changes:

Nucleotide-driven assembly: ATP binding promotes heptamer formation and subsequent double-ring assembly, unlike GroEL which forms stable tetradecamers without nucleotide [9]. The equatorial domain contains critical ATP-binding motifs (e.g., 85DGTTT89, G414, D494 in human mtHsp60) that mediate inter-subunit interactions [13].

Functional states: Hsp60 exists in equilibrium between single-ring "half-football" complexes (Hsp607-Hsp107) and double-ring "football" complexes (Hsp6014-(Hsp107)2) [9]. Both assemblies are functionally active in protein folding, with the double-ring form representing the ground state [9].

Lack of negative cooperativity: Unlike GroEL, Hsp60 does not display negative ATP-binding inter-ring cooperativity, allowing simultaneous ATP binding to both rings [9]. This fundamental mechanistic difference impacts the folding cycle and potential regulatory mechanisms.

Folding cycle: Client proteins bind to hydrophobic residues in the apical domain; ATP binding induces conformational changes that promote Hsp10 binding and encapsulation of the client within the folding chamber; ATP hydrolysis triggers release of the folded client [9] [14].

Figure 2: Hsp60 Oligomerization and Functional Cycle. ATP binding drives assembly from monomers to single rings, then to double rings; Hsp10 binding forms active football complexes; hydrolysis triggers disassembly.

Key Experimental Approaches for Hsp60 Oligomerization

Studying Hsp60 oligomerization requires techniques that capture dynamic assembly states:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Hsp60 Oligomerization Studies

| Reagent / Method | Specification / Function | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| SEC-MALS | Size-exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering | Determining oligomeric states and molecular weights in solution [9] |

| ADP:BeF3 | ATP ground-state mimic | Trapping and stabilizing football complexes for structural studies [9] |

| Cryo-EM single particle analysis | High-resolution structure determination of complexes | Visualizing football and half-football complexes at near-atomic resolution [9] |

| BS3 crosslinker | Chemical crosslinking with amine-reactive NHS esters | Stabilizing and identifying transient oligomeric states [13] |

| Temperature-controlled purification | Manipulating assembly stability | Isolating specific oligomeric forms (dimers at 4°C, heptamers at 25°C) [13] |

| Negative-stain TEM | Rapid structural assessment | Confirming ring-shaped structures and oligomeric states [13] |

| Obligate single-ring mutants | Engineered variants deficient in double-ring formation | Probing functional significance of different oligomeric states [9] |

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing Hsp60 Oligomeric States

- Temperature-Modulated Purification: Purify Hsp60 at 4°C to isolate dimeric forms and at 25°C to obtain heptameric/tetradecameric complexes [13].

- Complex Stabilization: Incubate Hsp60 with ATP and BeF3 to stabilize football complexes for structural studies [9].

- Oligomeric State Analysis: Use SEC-MALS to determine molecular weights and distributions of different oligomeric species in solution [9] [13].

- ATPase Activity Assays: Measure ATP hydrolysis kinetics across different oligomeric states; dimeric Hsp60 shows deficient ATPase activity [13].

- Structural Characterization: Apply single-particle cryo-EM to determine structures of football and half-football complexes at 3.0-3.8 Å resolution [9].

- Functional Complementation: Test obligate single-ring and double-ring mutants for in vivo function using bacterial complementation assays [9].

Comparative Analysis and Research Implications

Mechanistic Comparison of Hsp70 and Hsp60

Despite sharing fundamental roles in proteostasis, Hsp70 and Hsp60 employ strikingly different mechanistic strategies:

Table 5: Comparative Analysis of Hsp70 and Hsp60 Chaperone Systems

| Characteristic | Hsp70 System | Hsp60 System |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Mechanism | Allosteric regulation between NBD and SBD | Oligomeric assembly into folding chambers |

| Domain Architecture | Two-domain monomer (NBD + SBD) with flexible linker | Three-domain monomer (apical, intermediate, equatorial) |

| Functional Oligomerization | Primarily monomeric; cooperates with J-proteins and NEFs | Essential oligomerization (heptameric rings and tetradecamers) |

| Nucleotide Regulation | ATP/ADP cycling controls substrate affinity | ATP binding drives assembly and folding cycle |

| Substrate Recognition | Short hydrophobic stretches in extended conformations | Broader structural elements in folding intermediates |

| Co-chaperone Requirements | J-domain proteins and nucleotide exchange factors | Hsp10 (co-chaperonin) lid structure |

| Folding Environment | Transient binding without encapsulation | Sequestration in protected central cavity |

| Allosteric Properties | Bidirectional communication between domains | Inter-ring communication without negative cooperativity |

Research Applications and Therapeutic Implications

The distinct mechanisms of Hsp70 and Hsp60 present unique research and therapeutic opportunities:

Hsp70 as a therapeutic target: The allosteric regulation of Hsp70 makes it an attractive target for diseases of proteostasis. Small molecules that modulate the allosteric interface could potentially correct dysregulated chaperone function in neurodegenerative diseases and cancer [15] [16].

Hsp60 in disease contexts: The dynamic oligomerization of Hsp60 and its presence in extramitochondrial locations under pathological conditions suggests context-specific functions [10]. Different oligomeric states may play distinct roles in cancer progression and neurodegeneration, offering potential for selective therapeutic targeting [10].

Experimental design considerations: Research on these chaperones requires careful consideration of their dynamic nature. Hsp70 studies must account for nucleotide state and co-chaperone interactions, while Hsp60 research requires controls for oligomeric equilibrium and stabilization conditions [11] [13].

Technical advancements: Recent cryo-EM breakthroughs have enabled visualization of transient Hsp60 football complexes, while sophisticated NMR and single-molecule techniques have revealed Hsp70 allosteric dynamics at unprecedented resolution [7] [9].

The domain architecture of Hsp70, characterized by sophisticated NBD-SBD allostery, and the double-ring oligomerization of Hsp60 represent two elegant evolutionary solutions to the fundamental challenge of protein folding in the cellular environment. While Hsp70 operates through a dynamic, allosterically-regulated clamp mechanism ideal for binding transiently exposed hydrophobic segments, Hsp60 forms structured folding chambers that encapsulate clients entirely. Both systems exemplify the intricate relationship between protein structure and function in maintaining proteostasis. Their continued investigation not only deepens our understanding of basic cellular processes but also opens promising avenues for therapeutic intervention in the growing spectrum of protein conformation diseases. Future research directions include elucidating the full structural dynamics of these chaperones in their native environments, developing more specific chemical modulators, and exploring the therapeutic potential of manipulating their oligomeric states and allosteric networks.

Within the cellular machinery, molecular chaperones are essential guardians of protein homeostasis (proteostasis), ensuring the proper folding, assembly, and localization of proteins and mitigating the damage caused by proteotoxic stress [17] [18]. The 70 kDa and 60 kDa heat shock proteins, Hsp70 and Hsp60, are two central pillars of this chaperone network. Despite sharing a common goal of maintaining proteostasis, they employ distinct, sophisticated mechanisms centered on ATP-driven conformational switches to manage their client proteins [17]. This review delineates the core reaction cycles of Hsp70 and Hsp60, highlighting how ATP binding and hydrolysis power conformational changes that enable these chaperones to bind, fold, and release a diverse array of client substrates. A deep understanding of these mechanisms is paramount for developing novel therapeutic strategies against cancers, neurodegenerative diseases, and other conditions linked to chaperone malfunction [17] [6].

The Hsp70 Chaperone Cycle

Domain Architecture and Allosteric Regulation

Hsp70 chaperones are multi-domain proteins conserved from bacteria to humans. They consist of two principal structured domains [19] [18]:

- A 45 kDa N-terminal Nucleotide-Binding Domain (NBD)

- A 25 kDa C-terminal Substrate-Binding Domain (SBD) The SBD is further subdivided into a β-sandwich base (SBDβ) that forms the client binding pocket and an α-helical lid (SBDα). These domains are connected by a conserved, flexible linker that is critical for allosteric communication [18]. The NBD binds ATP and undergoes significant conformational changes during its hydrolysis. The SBD engages client proteins, preferring short stretches of hydrophobic amino acids flanked by basic residues [19] [20].

Table 1: Key Structural Domains of Hsp70 and Their Functions

| Domain | Molecular Weight | Primary Function | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-terminal Nucleotide-Binding Domain (NBD) | ~45 kDa | ATP binding and hydrolysis | Four subdomains (IA, IB, IIA, IIB) forming a cleft for nucleotide binding [19] [21] |

| C-terminal Substrate-Binding Domain (SBD) | ~25 kDa | Client protein recognition and binding | SBDβ (base): hydrophobic binding groove; SBDα (lid): regulates client access [19] [18] |

| Flexible Linker | Variable | Allosteric communication | Connects NBD and SBD; conformation changes with nucleotide state [18] |

The ATP-Driven Conformational Switch

The functional cycle of Hsp70 is governed by an allosteric mechanism that couples nucleotide state in the NBD to client affinity in the SBD [18].

- ATP-Bound State (Open Conformation): When ATP is bound in the NBD, the Hsp70 complex adopts an open conformation. The SBDα lid is retracted, and the SBDβ exhibits low affinity for client proteins. This state allows for rapid binding and release of client substrates [18].

- ATP Hydrolysis and Client Trapping: The ATPase activity of Hsp70, while intrinsically low, is dramatically stimulated by J-protein co-chaperones (Hsp40). Hsp40 delivers client proteins to the SBD and interacts with the Hsp70 NBD to trigger ATP hydrolysis [19] [18]. The energy from hydrolysis is transduced via the linker, causing the SBDα lid to close over the client protein, trapping it in the SBD with high affinity [18].

- ADP-Bound State (Closed Conformation): In the ADP-bound state, the chaperone remains in a closed conformation, stably associated with the client. This provides a protected environment, preventing the client from aggregating [17].

- Nucleotide Exchange and Client Release: The release of ADP is rate-limiting and is accelerated by Nucleotide Exchange Factors (NEFs) such as GrpE in bacteria or Bag-1 and Hsp110 in eukaryotes. NEFs pry the NBD open, facilitating the exchange of ADP for ATP. Once ATP binds, the cycle resets to the open conformation, releasing the folded or now-competent client protein [19] [21] [18].

This cycle enables Hsp70 to function as a "multiple socket," providing a platform where client proteins can be handed off to other chaperones or degradation systems based on the specific co-chaperones present [18].

Mechanism of Client Recognition

A fundamental characteristic of Hsp70 is its mode of client recognition. Research using solution NMR spectroscopy has established that both bacterial and human Hsp70 interact with clients via a conformational selection (CS) mechanism [20]. Hsp70 does not actively unfold its clients; instead, it selectively binds to pre-existing unfolded or partially unfolded conformations from a dynamic ensemble of interconverting client structures. This ensures that Hsp70 primarily engages non-native proteins while leaving natively folded proteins undisturbed [20].

Diagram 1: The Hsp70 ATP-driven chaperone cycle.

The Hsp60 Chaperonin Cycle

Structure and Classification

Hsp60 chaperonins, also known as Cpn60, form large, multi-subunit complexes that provide an encapsulated folding chamber for client proteins. They are classified into two groups [1] [22]:

- Group I: Found in eubacteria (GroEL), mitochondria (mtHSP60), and chloroplasts. They form a double-ring structure of 7 subunits per ring and require a dedicated co-chaperone lid (GroES in bacteria, HSP10 in eukaryotes) to function [1].

- Group II: Found in archaea and the eukaryotic cytosol (TRiC/CCT). They form double rings of 8 or 9 subunits per ring and have a built-in lid structure, making them independent of a GroES-like co-chaperone [1] [22].

The prototypical Group I chaperonin, GroEL, is a tetradecamer arranged in two back-to-back heptameric rings. Each subunit comprises three domains [1]:

- Equatorial Domain: Contains the ATPase activity and provides the main inter-ring and intra-ring contacts.

- Apical Domain: Forms the opening of the folding chamber and contains hydrophobic residues for client binding.

- Intermediate Domain: Connects the equatorial and apical domains and acts as a hinge during conformational changes.

Table 2: Comparison of Group I and Group II Chaperonins

| Feature | Group I Chaperonins (e.g., GroEL, mtHSP60) | Group II Chaperonins (e.g., TRiC/CCT) |

|---|---|---|

| Organisms | Eubacteria, Mitochondria, Chloroplasts | Archaea, Eukaryotic Cytosol |

| Ring Structure | Two heptameric rings (7+7) | Two octameric or nonameric rings (8+8/9+9) |

| Lid Mechanism | Requires separate GroES/HSP10 co-chaperone lid | Built-in lid formed by apical domain extensions |

| Folding Chamber | Encapsulates client in an isolated environment | Encapsulates client in an isolated environment |

The Folding Cycle and Coordinated Conformational Changes

The GroEL/GroES reaction cycle is a finely tuned process driven by ATP binding and hydrolysis, characterized by negative cooperativity between the two rings: when one ring is in a high-affinity state for ATP, the other is in a low-affinity state [1] [22].

Diagram 2: The GroEL/GroES (Hsp60/Hsp10) folding cycle.

The cycle proceeds as follows [1]:

- Client Binding: An unfolded client protein binds to the hydrophobic apical domains of one ring (the cis ring) of GroEL, which is in a nucleotide-free or ADP-bound state.

- Encapsulation: The binding of ATP and the co-chaperone GroES to the same cis ring triggers dramatic, concerted conformational changes. The apical domains undergo an upward and outward rotation, displacing the client protein into the now-enlarged and hydrophilic folding chamber. The chamber becomes encapsulated, isolating the client from the bulk cytosol.

- Folding: The client protein has a defined timeframe (the timescale of ATP hydrolysis, ~10-15 seconds) to fold within this protected Anfinsen cage.

- Release: The binding of ATP and a new client protein to the opposite trans ring acts as a allosteric trigger that discharges GroES, ADP, and the folded (or folding-competent) client from the cis ring. If the client has not reached its native state, it may rebind for another round of folding.

This alternating cycle of the two rings ensures continuous client processing [1] [22].

Experimental Analysis of Chaperone Mechanisms

Key Methodologies and Reagents

Understanding the conformational dynamics and client interactions of Hsp70 and Hsp60 relies on a suite of sophisticated biophysical and biochemical techniques.

Table 3: Key Experimental Protocols for Studying Chaperone Mechanisms

| Methodology | Application & Rationale | Key Experimental Insights |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Probing functional residues (e.g., ATPase site, client binding pocket). An R261A mutation in Hsp70 NBD was shown to alter ATP kinetics and fluorescence quenching [21]. | Validated computational predictions of allosteric communication pathways and identified critical residues for function [21]. |

| All-Atom Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Modeling atomic-level conformational dynamics and allosteric transitions. Simulations of Hsp70 NBD revealed a more closed ATP-bound state than seen in crystal structures [21]. | Predicted novel conformational states and provided atomic-level mechanisms for allostery and conformational selection [21] [20]. |

| Solution NMR Spectroscopy | Characterizing structure, dynamics, and binding events under native conditions. Used to quantify conformational selection in Hsp70-client interactions [20]. | Established that Hsp70 selects unfolded client conformations from a pre-existing ensemble, and defined the structural state of clients when bound [20]. |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Monitoring conformational changes in real-time. Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (e.g., Trp90 in Hsp70) reports on nucleotide-dependent domain rearrangements [21]. | Provided kinetic data on ATP-induced conformational changes and validated allosteric models derived from structures and simulations [21]. |

| X-ray Crystallography & Cryo-EM | Determining high-resolution structures of chaperones and their complexes. Revealed structures of GroEL/GroES and various Hsp70 conformational states [1] [6]. | Provided the foundational structural frameworks for understanding domain organization and large-scale quaternary changes [1] [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chaperone Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Chaperones (Hsp70, Hsp60, GroEL/ES) | Purified proteins for in vitro folding assays, structural studies, and biochemical characterization. | Core component for ATPase assays, client refolding experiments, and structural biology [1] [20]. |

| Co-chaperone Proteins (Hsp40, GrpE, Bag-1, Hsp110) | Regulate the ATPase cycle of Hsp70. Essential for reconstituting functional cycles in vitro. | Used to study stimulation of ATP hydrolysis (Hsp40) and nucleotide exchange (GrpE, Bag-1) [19] [18]. |

| Site-Directed Mutants (e.g., R261A Hsp70) | To dissect the functional contribution of specific amino acid residues. | The R261A Hsp70 mutant helped confirm the role of Arg261 in ATP-induced conformational changes and fluorescence quenching [21]. |

| Isotope-labeled Substrates (e.g., 15N, 13C-labeled clients) | Enables high-resolution NMR studies of chaperone-client interactions and client conformations. | Critical for determining that Hsp70 binds clients via conformational selection [20]. |

| Fluorescent Nucleotide Analogs (e.g., mant-ATP/ADP) | Report on nucleotide binding and dissociation kinetics. | Used in stopped-flow experiments to measure nucleotide affinity and the effects of NEFs and clients [21]. |

Hsp70 and Hsp60 exemplify nature's sophisticated solutions to the complex problem of protein homeostasis. While both are ATP-dependent molecular machines, their mechanisms are distinct. Hsp70 operates as a versatile "triage" chaperone, using a allosteric two-domain switch to selectively bind and release unfolded clients in a process governed by conformational selection and tightly regulated by co-chaperones [20] [18]. In contrast, Hsp60 functions as a specialized folding cage, utilizing a complex, cooperative two-ring system to physically encapsulate a single client protein, providing it with a protected environment to reach its native conformation [1] [22]. The continued elucidation of these ATP-driven cycles, through integrative structural biology, biophysics, and computation, not only deepens our fundamental understanding of cellular physiology but also paves the way for targeting these essential chaperones in human disease [17] [6].

Within the complex cellular environment, the maintenance of protein homeostasis (proteostasis) is a fundamental process, with molecular chaperones serving as the primary machinery for ensuring proper protein folding, preventing aggregation, and mediating cellular stress responses [1] [23]. The 70-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp70) and chaperonin (Hsp60) families represent two central pillars of this proteostasis network. While these chaperones form the core folding machinery, their functional specificity and regulation are critically dependent on dynamic interactions with co-chaperones [24] [25]. This orchestration is achieved through specialized co-chaperone networks: J-domain proteins (JDPs) and nucleotide exchange factors (NEFs) for the Hsp70 system, and Hsp10 for the Hsp60 system. These co-chaperones transform generic chaperone scaffolds into precise, regulated machines capable of handling a diverse array of client proteins and complex cellular challenges [26] [27]. Understanding the mechanisms of these cooperative systems is not only fundamental to cell biology but also provides crucial insights for developing therapeutic interventions for protein misfolding diseases, including neurodegeneration and cancer [1] [25].

The Hsp70 Chaperone System

The Hsp70 system is a versatile chaperone machine involved in a wide range of cellular processes, including de novo protein folding, prevention of protein aggregation, membrane translocation, and disassembly of protein complexes [23]. Its function is governed by an allosteric ATPase cycle that regulates its affinity for client proteins.

Core Mechanism of the Hsp70 Chaperone Cycle

Hsp70 consists of two primary domains: an N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) that hydrolyzes ATP, and a C-terminal substrate-binding domain (SBD) that interacts with client proteins [25] [23]. The chaperone alternates between two conformational states:

- ATP-bound state: The SBD exhibits fast substrate association and dissociation rates, characterized by an open lid structure.

- ADP-bound state: The SBD has slow substrate kinetics, with a closed lid that tightly traps client proteins.

The intrinsic ATPase activity of Hsp70 is low, and the switching between these states requires precise regulation by co-chaperones to achieve efficient client protein folding and processing [25] [23].

J-domain Proteins (JDPs): Specificity Factors for Hsp70

J-domain proteins (JDPs), also known as Hsp40s, constitute the largest family of Hsp70 co-chaperones and play a determinative role in specifying Hsp70 functions [24] [26].

Table 1: Classification of J-domain Proteins (JDPs)

| Class | Domain Architecture | Representative Members | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class A | J-domain → G/F region → Zinc-finger domain → C-terminal domain (CTD) | E. coli DnaJ, Yeast Ydj1 | Most similar to bacterial DnaJ; contain zinc finger motifs |

| Class B | J-domain → G/F region → Domain without zinc finger | Human DNAJB1, Yeast Sis1 | Lack zinc-binding motifs; may have other substrate interaction domains |

| Class C | J-domain with varied other domains | Diverse species-specific JDPs | Largest class; diverse domain architectures beyond typical JDP structure |

JDPs share a defining ~70 amino acid J-domain that contains a conserved His-Pro-Asp (HPD) motif essential for stimulating Hsp70's ATPase activity [26]. The J-domain interacts with the ATP-bound state of Hsp70, contacting lobe IIA of the NBD, the inter-domain linker, and the β-sandwich of the SBD [26]. This multi-site interaction couples substrate binding to ATP hydrolysis, enabling the synergistic action of substrates and J-domains in stimulating the Hsp70 ATPase cycle [26].

Beyond their J-domains, these co-chaperones possess diverse additional domains that drive functional specificity by delivering particular substrates or recruiting Hsp70 to specific cellular locations [24] [26]. In multicellular organisms, JDP expression shows tissue and cell-type heterogeneity, allowing specialized proteostasis networks tailored to distinct cellular environments [26].

Nucleotide Exchange Factors (NEFs): Completing the Hsp70 Cycle

Following ATP hydrolysis and client protein binding, the release of ADP from Hsp70 becomes rate-limiting for the chaperone cycle. Nucleotide Exchange Factors (NEFs) catalyze this critical step, facilitating the transition from the ADP-bound to ATP-bound state and subsequent client release [28] [25].

Table 2: Nucleotide Exchange Factor (NEF) Families in Eukaryotes

| NEF Family | Structure | Representative Members | Mechanistic Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp110 (Hsp70-related) | NBD, β-sandwich, 3-helix bundle | Mammalian Hsp110, Yeast Sse1p/Sse2p | Binds Hsp70 NBD, induces conformational change for ADP release |

| BAG Domain | BAG domain | BAG-1, BAG-3 | Interacts with Hsp70 NBD, accelerates nucleotide exchange |

| HspBP1 | Armadillo repeats | HspBP1, Fes1p | Binds Hsp70 NBD, disrupts nucleotide binding site |

| GrpE | Dimeric structure | Mitochondrial GrpE | Bacterial homolog; functions as homodimer |

The Hsp110 family represents a specialized subclass of NEFs that are themselves homologs of Hsp70 but have evolved to primarily function as NEFs rather than canonical chaperones [28]. Structural studies of the yeast Hsp110 Sse1 in complex with the Hsp70 NBD reveal that Hsp110 embraces the Hsp70 NBD, inducing structural changes that open the nucleotide-binding cleft and facilitate ADP release [29]. This NEF activity is essential for cellular viability, as demonstrated by the synthetic lethality observed in yeast lacking both SSE1 and SSE2 genes [28].

The functional importance of this regulation is evidenced by experimental findings that equimolar amounts of Sse1p increase the rate of nucleotide exchange on the yeast Hsp70 Ssa1p by approximately 12-fold, significantly outperforming other NEFs like Fes1p [28]. This efficient nucleotide exchange directly enhances Hsp70-mediated refolding of denatured proteins, as demonstrated with thermally denatured firefly luciferase [28].

The Hsp60 Chaperonin System

The Hsp60 family, also known as chaperonins, represents a distinct class of chaperones that form large, barrel-shaped complexes that provide an isolated environment for protein folding [1] [27].

Structural Organization and Classification

Chaperonins are classified into two main groups based on their structure and occurrence:

Table 3: Classification of Chaperonin Systems

| Group | Representative Complexes | Structure | Co-chaperone Requirement | Cellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | GroEL (bacteria), HSP60/HSP10 (mitochondria) | Double 7-mer ring | Hsp10 (GroES) co-chaperone essential | Bacteria, mitochondria, chloroplasts |

| Group II | TRiC/CCT (eukaryotic cytosol), Thermosome (archaea) | Double 8-9-mer ring | Built-in lid; prefoldin co-factor | Eukaryotic cytosol, archaea |

Group I chaperonins, such as the well-characterized GroEL/GroES system in E. coli and the homologous HSP60/HSP10 system in mammalian mitochondria, form symmetrical double-ring complexes with seven subunits per ring [1] [27]. Each subunit consists of three domains: equatorial (mediating ring-ring interactions and ATP binding), intermediate (acting as a hinge), and apical (containing the substrate-binding sites) [27].

Hsp10 Cooperation in the Chaperonin Folding Cycle

Hsp10 (known as GroES in bacteria) functions as a essential co-chaperone for Group I chaperonins, forming a dome-like structure that seals the folding chamber [1] [27]. The cooperative mechanism follows a well-defined sequence:

- Client protein binding: Unfolded substrate proteins bind to hydrophobic residues in the apical domains of the open GroEL (Hsp60) ring.

- Hsp10 binding: ATP and Hsp10 bind cooperatively to the same ring, causing dramatic conformational changes that elevate and twist the apical domains.

- Folding encapsulation: The Hsp10 "lid" seals the chamber, creating an isolated environment that shields the client protein from the crowded cellular milieu.

- Folding and release: ATP hydrolysis in the cis-ring and ATP binding to the trans-ring trigger Hsp10 and substrate release, typically after a complete catalytic cycle of approximately 10-15 seconds.

This mechanism allows proteins up to ~60 kDa to fold within the protected central cavity, which provides essential isolation from potential aggregation partners in the cellular environment [27]. The encapsulation event also induces a conformational shift from hydrophobic to hydrophilic surfaces in the folding chamber, promoting proper protein folding rather than aggregation [1].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Co-chaperone Networks

Key Methodologies and Reagents

Advanced experimental techniques have been essential for elucidating the mechanisms of co-chaperone networks.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Approaches

| Research Tool | Experimental Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent MABA-ADP | Stopped-flow fluorimetry to measure nucleotide exchange rates | Quantitative analysis of NEF activity; Sse1p accelerates Ssa1p nucleotide release 12-fold [28] |

| Recombinant Hsp70/Hsp40/NEF systems | In vitro refolding assays with denatured substrates (e.g., firefly luciferase) | Demonstration that optimal Sse1p concentrations boost Hsp70-mediated refolding yield and rate [28] |

| X-ray crystallography of Sse1p-Hsp70 complexes | Structural analysis of co-chaperone:chaperone interactions | Revealed how Hsp110 embraces Hsp70 NBD to induce ADP release [29] |

| Yeast genetics (SSE1/SSE2 deletion strains) | In vivo analysis of co-chaperone function | Established essential role of Hsp110 NEF activity; synthetic lethality of double deletions [28] |

| Small molecule inhibitors (MKT-077, JG-98) | Modulating Hsp70-co-chaperone interactions | Identification of allosteric sites that disrupt Hsp70-BAG interactions; potential therapeutic applications [25] |

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates a representative experimental approach for analyzing nucleotide exchange factor activity, a key methodology in co-chaperone research:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for measuring NEF activity using fluorescent MABA-ADP. The fluorescence of MABA-ADP decreases upon release from Hsp70, allowing quantification of nucleotide exchange rates [28].

Chaperone-Co-chaperone Functional Relationships

The functional integration between chaperones and their co-chaperones can be visualized as a coordinated network:

Diagram 2: Functional relationships in chaperone-co-chaperone networks. JDPs target substrates to Hsp70 and stimulate ATP hydrolysis, while NEFs reset the cycle by promoting ADP release. In the Hsp60 system, Hsp10 forms a sealed folding chamber for client encapsulation [28] [1] [26].

Implications for Disease and Therapeutic Development

The critical role of co-chaperone networks in proteostasis has profound implications for human disease, particularly in neurodegeneration and cancer [25] [30].

In neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and Huntington's disease, dysfunction of the Hsp70 co-chaperone system contributes to the accumulation of misfolded proteins [25]. For example, Hsp70 in complex with specific JDPs can disassemble tau fibrils but may generate seeding-competent oligomeric tau species in the process [25]. Similarly, mutations in synaptic JDPs like DNAJC5 (CSPα) and DNAJC6 (auxilin) cause adult neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis and early-onset Parkinson's disease, respectively, highlighting the specialized functions of these co-chaperones in neuronal proteostasis [30].

Therapeutic strategies are increasingly targeting specific co-chaperone interactions rather than the general chaperone machinery to avoid detrimental side effects [25]. Small molecules like JG-98 that allosterically inhibit Hsp70-BAG interactions have shown promise in modulating chaperone function for therapeutic benefit, illustrating the potential of targeting co-chaperone networks for drug development [25].

Co-chaperone networks represent sophisticated regulatory systems that confer specificity, efficiency, and functional diversity to the core chaperone machinery. J-domain proteins and nucleotide exchange factors partner with Hsp70 to form a dynamic system capable of responding to diverse protein folding challenges, while Hsp10 cooperation with Hsp60 creates an essential protected environment for proper protein folding. Continued elucidation of these cooperative mechanisms will not only advance our fundamental understanding of cellular proteostasis but also provide novel therapeutic avenues for the growing number of diseases associated with protein misfolding and aggregation. The integrated view presented in this review highlights the complexity and elegance of these essential cellular systems and underscores their importance in both health and disease.

Within the cellular milieu, molecular chaperones are fundamental components of the protein homeostasis (proteostasis) network, responsible for recognizing, binding, and assisting in the folding of non-native proteins. Their function prevents the toxic consequences of protein aggregation, a hallmark of numerous age-related diseases [17] [31]. The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone families are central to this proteostasis machinery, utilizing distinct but complementary mechanisms to manage substrate proteins. The core principle underlying substrate recognition across these chaperone families is the specific detection of hydrophobic amino acid patches that are exposed in non-native, misfolded, or unfolding polypeptides [32] [33]. These hydrophobic surfaces, which are typically buried within the core of correctly folded proteins, represent a danger of aberrant interactions that can lead to aggregation. By binding these patches, chaperones effectively shield them, thereby preventing aggregation and allowing folding to proceed correctly [33] [31]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the mechanisms by which Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperones recognize their substrates and prevent aggregation, framed within the context of modern proteostasis research for a scientific audience.

Hsp70 Chaperone System: Mechanism of Substrate Recognition

Structural Domains and Allosteric Regulation

The Hsp70 chaperone system, comprising Hsp70 (DnaK in bacteria) and its co-chaperones, operates as a central hub in proteostasis, assisting in a wide range of processes including de novo folding, refolding, and translocation [17] [33]. Hsp70 proteins share a conserved architecture consisting of two primary domains:

- N-terminal Nucleotide-Binding Domain (NTD): This domain exhibits ATPase activity.

- C-terminal Substrate-Binding Domain (SBD): This domain is responsible for binding client proteins.

These two domains are connected by a flexible linker [17]. The SBD is further subdivided into a β-sandwich subdomain (SBDβ) that houses the hydrophobic peptide-binding pocket and an α-helical lid (SBDα) [17]. The chaperone activity of Hsp70 is governed by an allosteric mechanism tied to its ATPase cycle. When the NTD is bound to ATP, the SBD adopts an open conformation characterized by low affinity for substrates and fast binding/dissociation kinetics. Hydrolysis of ATP to ADP triggers a conformational shift that closes the lid, resulting in a high-affinity state that stably traps the substrate [17] [33]. This cycle is critically regulated by co-chaperones; Hsp40 (DnaJ) proteins act as J-proteins that stimulate Hsp70's ATPase activity and often deliver initial substrates, while nucleotide exchange factors (e.g., GrpE in E. coli) promote the release of ADP, allowing a new ATP to bind and substrate release [17] [6].

Specificity for Hydrophobic Patches

Hsp70 chaperones recognize short, degenerate peptide stretches of approximately 7 amino acids within their substrate proteins [34]. The core recognition motif is hydrophobic in nature, typically enriched with branched-chain aliphatic amino acids like leucine and isoleucine [34] [33]. The SBDβ domain contains a specific pocket that accommodates these hydrophobic residues, while flanking regions of the substrate peptide may interact with more polar areas of the binding groove. This mechanism allows Hsp70 to bind to a vast repertoire of partially folded or unfolded proteins, as these hydrophobic segments are transiently exposed during folding or become permanently accessible in misfolded states [33]. The primary role of the Hsp70 system is often described as a "holdase" or "gatekeeper," minimizing aggregation of nascent chains and unfolded proteins by binding hydrophobic patches, thereby keeping them in a folding-competent state before they may be transferred to other chaperone systems like Hsp60 for active folding [33].

Hsp60 Chaperone System: Encapsulation for Folding

The GroEL-GroES Complex Architecture

In contrast to the more open binding mode of Hsp70, the Hsp60 chaperonin system, exemplified by the GroEL-GroES complex in bacteria, provides an encapsulated environment for protein folding. GroEL is a large, double-ring structure composed of 14 identical subunits arranged in two heptameric rings stacked back-to-back [17]. Each ring defines a central cavity that serves as the folding chamber. The co-chaperonin GroES is a single heptameric ring that acts as a lid for the GroEL complex [17] [33].

The internal surface of the GroEL cavity is predominantly hydrophilic, which provides an environment that discourages aggregation and promotes proper folding, in stark contrast to the hydrophobic binding surfaces used for initial substrate recognition [33]. The folding process is ATP-dependent. A partially folded substrate protein is captured by the hydrophobic apical domains of the open GroEL ring. ATP binding to the ring facilitates the binding of GroES, which triggers a massive conformational change: the apical domains rotate and elevate, sequestering the substrate inside the now hydrophilic, encapsulated chamber. This process promotes folding during a timescale set by the ATP hydrolysis cycle within the ring. Upon ATP hydrolysis in the encapsulated ring and subsequent ATP binding to the opposite ring, the lid is released, and the substrate, whether folded or not, is discharged [17] [33].

Recognition at the Hydrophobic Apical Domain

Substrate recognition by GroEL does not rely on a specific linear sequence motif but is mediated by flexible hydrophobic residues located in the apical domains of the GroEL subunits [33]. These hydrophobic patches, which include residues such as Val, Leu, and Ile, interact with complementary hydrophobic surfaces exposed on non-native substrate proteins. This interaction is relatively promiscuous, allowing GroEL to assist in the folding of a diverse set of cytosolic proteins, typically in the size range of 20-60 kDa [33]. The binding itself helps to prevent off-pathway aggregation interactions. The subsequent conformational change that occurs upon GroES binding serves a critical dual function: it physically separates the substrate from the bulk solvent and other folding intermediates, and it removes the substrate from the initial hydrophobic binding sites, shifting it into the hydrophilic folding cage. This "forced unfolding" mechanism can disrupt misfolded structures, giving the substrate a fresh opportunity to reach its native conformation [33].

Table 1: Comparative Features of Hsp70 and Hsp60 Chaperone Systems

| Feature | Hsp70 System | Hsp60 (GroEL-GroES) System |

|---|---|---|

| Core Components | Hsp70 (DnaK), Hsp40 (DnaJ), NEF (GrpE) | GroEL (Hsp60), GroES (Hsp10) |

| Structural Organization | Monomeric; two-domain structure | Double-ring tetradecamer with a lid |

| ATP Dependency | ATP-dependent allosteric control | ATP-dependent encapsulation |

| Primary Recognition Motif | Short hydrophobic peptide stretches (~7 residues) | Exposed hydrophobic surfaces on non-native proteins |

| Binding Site | Hydrophobic pocket in the SBDβ | Hydrophobic patches on apical domains |

| Folding Environment | Open binding; no encapsulation | Secluded, hydrophilic Anfinsen cage |

| Primary Role in Proteostasis | Holdase; prevents aggregation of nascent/unfolded chains | Foldase; provides isolated compartment for folding |

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Chaperone-Substrate Interactions

Elucidating the dynamic interactions between chaperones and their substrates requires sophisticated biochemical and biophysical techniques. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments cited in research.

Aggregation Prevention Assay

A standard in vitro method to quantify chaperone activity is to monitor its ability to prevent the aggregation of a model substrate under stress conditions [32].

Protocol:

- Substrate Denaturation: A model substrate protein (e.g., citrate synthase or rhodanese) is first denatured in a buffer containing 6 M guanidine-HCl and a reducing agent like DTT [32].

- Refolding Initiation: The denatured substrate is rapidly diluted 100-fold into a refolding buffer. This dilution initiates aggregation as the protein begins to refold and expose hydrophobic surfaces.

- Turbidity Measurement: The sample is placed in a spectrophotometer, and light scattering (turbidity) is monitored by measuring the absorbance at 360 nm for a set period (e.g., 10-30 minutes) at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C). Aggregation manifests as an increase in optical density.

- Data Analysis: The aggregation kinetics in the presence of the chaperone are compared to a control containing only the substrate. Raw absorbance data are normalized, and relative aggregation is calculated as the fraction of the final absorbance value observed in the control. Effective chaperones will significantly reduce or eliminate the increase in turbidity [32].

READ Method for Visualizing Dynamic Complexes

The Residual Electron and Anomalous Density (READ) method is a novel X-ray crystallography approach designed to visualize heterogeneous and dynamic complexes, such as those between a chaperone and its unfolding substrate [35].

Protocol:

- Complex Crystallization: Co-crystallize the chaperone (e.g., E. coli Spy) with a substrate protein (e.g., Im7).

- Anomalous Scatterer Incorporation: Engineer variants of the substrate where individual residues are replaced with the non-canonical amino acid 4-iodophenylalanine (pI-Phe), a strong anomalous scatterer. Co-crystallize the chaperone with each single-substitute substrate variant [35].

- Data Collection: Collect X-ray diffraction data and anomalous data for each crystal.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: Generate a large, diverse pool of possible chaperone-substrate complex conformations using coarse-grained MD simulations.

- Sample-and-Select Algorithm: A computational algorithm iteratively selects the minimal ensemble of conformations from the MD pool that best fits both the residual electron density and the collected anomalous signals from the iodine atoms.

- Validation: The final structural ensemble is validated using multiple statistical tests, resulting in a high-resolution view of the various conformational states the substrate samples while bound to the chaperone [35].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the READ method.

Analysis of Hydrophobic Motif Function

To define the role of specific hydrophobic motifs in chaperone activity, such as in BRICHOS or prefoldin domains, researchers employ loop-swap and point mutation strategies [32] [36].

Protocol:

- Sequence Analysis: Identify short, conserved hydrophobic sequence motifs (e.g., tripeptides) in an unstructured loop region of a chaperone domain [36].

- Construct Design:

- Loop-Swap Variants: Replace the native loop in an active chaperone (e.g., Bri2 BRICHOS) with the corresponding loop from a chaperone-inactive homolog (e.g., proSP-C BRICHOS), and vice versa [36].

- Point Mutants: Systematically mutate key hydrophobic residues in the motifs to alanine or more polar residues to reduce hydrophobicity.

- Protein Purification: Express and purify the wild-type and variant chaperone proteins.

- Activity Assay: Test the chaperone activity of all variants using the aggregation prevention assay (see 4.1). The relative activity is quantified and correlated with the biological hydrophobicity of the motifs [36].

- Oligomerization Analysis: Use techniques like analytical size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) to determine if mutations affect the chaperone's assembly state, as oligomerization is often required to display multiple hydrophobic motifs [32] [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table details essential reagents and materials used in experimental studies of chaperone function.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Chaperone Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Model Amyloidogenic Substrates | To study chaperone inhibition of fibril formation. | Aβ42 (Alzheimer's disease), α-Synuclein (Parkinson's disease). Monitored by Thioflavin T fluorescence [31]. |

| Model Amorphous Aggregation Substrates | To study chaperone prevention of non-fibrillar aggregation. | Citrate Synthase (CS), Rhodanese (Rho), Malate Dehydrogenase (MDH). Unfold at high temperature; aggregation monitored by light scattering [32] [36]. |

| Anomalous Scatterers | To locate specific residues in dynamic complexes via X-ray crystallography. | 4-Iodophenylalanine (pI-Phe): A non-canonical amino acid with a strong anomalous signal for precise positioning [35]. |

| Chaperone Activity Assay Kits | Commercial solutions for standardized activity measurement. | Kits based on light scattering of a standard substrate (e.g., CS or MDH) in the presence of a test chaperone. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | To analyze chaperone oligomeric state and complex formation. | Superdex S200HR: Used for analytical SEC to separate oligomers, dimers, and monomers of chaperones like prefoldin and BRICHOS [32] [36]. |

Advanced Research and Therapeutic Implications

Beyond Hydrophobicity: The Role of Electrostatics

While hydrophobic interactions are the primary driving force for substrate recognition, recent research highlights the important role of electrostatic interactions in modulating chaperone activity. For example, engineering the chaperone Spy to increase the positive charge on its surface was shown to enhance its anti-aggregation activity for a variety of substrates. This suggests that attractive electrostatic forces can guide non-native proteins to the chaperone's binding surface, increasing the association rate constant (k~on~) and overall efficiency, without altering the fundamental hydrophobic binding mechanism [37]. This combination of hydrophobic binding and electrostatic steering may be a general feature that enhances the capacity and speed of the cellular chaperone network.

Chaperones in Longevity and Disease

The critical role of chaperones in proteostasis is underscored by their correlation with longevity and involvement in human disease. Comparative studies across vertebrate species have shown that longer-lived mammals and birds consistently exhibit higher constitutive expression levels of Hsp60, Hsp70, GRP78, and GRP94 in tissues like liver, heart, and brain [38]. This suggests that the evolution of longevity is supported by an enhanced proteostasis network with a greater capacity to prevent protein damage and aggregation over a longer lifespan [38]. Conversely, a decline in chaperone function is implicated in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Here, chaperones like Hsp70 and small HSPs can interact with amyloidogenic proteins (e.g., Aβ, α-synuclein) at various stages of the aggregation pathway, inhibiting primary nucleation, secondary nucleation, and elongation, or even mediating the detoxification of amyloid fibrils [31].

Targeting Chaperones for Drug Discovery

The clear link between chaperone malfunction and disease has positioned them as promising therapeutic targets. The field has evolved through several stages:

- Stage 1 (Pan-isoform inhibition): Development of small-molecule inhibitors (e.g., for Hsp90) without initial regard for isoform selectivity.

- Stage 2 (Isoform-selective inhibition): Designing inhibitors that target specific isoforms of HSP families (e.g., cytosolic HSP90α vs. ER-resident GRP94) to improve specificity and reduce side effects.

- Stage 3 (Targeting PPIs): Developing compounds that disrupt specific protein-protein interactions (PPIs) between HSPs and their co-chaperones or client proteins.

- Stage 4 (Multi-specific molecules): The latest frontier involves designing bi- or multi-specific molecules that simultaneously target different components of the chaperone network for enhanced efficacy and selectivity [6].

The following diagram illustrates the progression of these therapeutic strategies.

Cellular compartmentalization, a defining feature of eukaryotic cells, establishes distinct biochemical environments within membrane-bound organelles, allowing separate metabolic reactions and specialized functions to occur simultaneously and efficiently. This physical separation minimizes conflicting side reactions, prevents accidental enzyme inhibition, and enables cells to increase internal surface areas for critical reactions through organelle membranes [39]. The functional specialization achieved through compartmentalization is fundamentally supported by molecular chaperones, which ensure proper protein folding, assembly, and quality control within each cellular compartment [16].

The proteostasis network—an integrated system of molecular chaperones, folding enzymes, and degradation machineries—maintains protein homeostasis differently in each compartment [16]. Molecular chaperones, particularly those from the heat shock protein (HSP) families, have evolved specialized forms and regulatory mechanisms tailored to the unique environments and client proteins of the cytosol, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum. This review examines the compartment-specific functions of the Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone systems, their mechanisms of action, and their critical roles in maintaining cellular proteostasis.

Compartment-Specific Chaperone Systems

The Cytosolic Hsp70 Chaperone Network

The 70-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp70) chaperone system in the cytosol represents a paradigm of "selective promiscuity," interacting with a wide range of substrate proteins while minimizing undesired interactions [40]. Cytosolic Hsp70 facilitates the folding, assembly, membrane translocation, and quality control of nascent polypeptide chains and stress-denatured proteins through an ATP-dependent binding and release cycle.

Mechanism and Regulation: Hsp70 achieves its functional versatility through sophisticated regulation by co-chaperones. J-domain proteins (JDPs) and nucleotide exchange factors (NEFs) are key to substrate recognition, remodeling, and release from chaperone complexes [40]. The approximately 50 human JDPs confer remarkable client specificity to Hsp70s, with some JDPs targeting Hsp70s to specific subcellular locations ("recruiters") while others bind substrates directly as "specialists" or "generalists" [40]. Different JDPs, together with NEFs, dictate the fate of Hsp70 clients by directing them toward distinct protein quality control pathways, resulting in either folding or degradation [40].

Functional Specialization: The cytosolic Hsp70 system demonstrates remarkable adaptation to its environment through:

- Collaboration with other chaperones: Hsp70 works with Hsp90 in multi-chaperone complexes for folding specific client classes, such as kinases and transcription factors [6].

- Integration with degradation pathways: Through co-chaperones like BAG-1, Hsp70 can target irreversibly damaged proteins for proteasomal degradation [41].

- Stress adaptation: Under heat stress, Hsp70 expression increases dramatically to prevent aggregation of denatured proteins and facilitate refolding [41].

Table 1: Key Components of the Cytosolic Hsp70 System

| Component | Type | Function | Regulatory Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp70 (HSPA1A, HSPA8) | Core Chaperone | ATP-dependent substrate binding/release | Protein folding, translocation, complex assembly |

| Hsp40 (DNAJA, DNAJB, DNAJC) | J-domain Protein | Stimulates Hsp70 ATPase activity | Substrate targeting and specificity |

| BAG-1, BAG-3 | Nucleotide Exchange Factor | Promotes ADP release from Hsp70 | Determines client fate (degradation vs. folding) |

| Hsp110 | NEF | Specialized NEF for Hsp70 | Enhances folding efficiency under stress |

| CHIP | Co-chaperone | E3 ubiquitin ligase | Targets Hsp70 clients for degradation |

Mitochondrial Chaperone Systems: Hsp60 and Hsp70

Mitochondria contain specialized chaperone systems in different sub-compartments that are essential for maintaining mitochondrial proteostasis and overall function. The mitochondrial matrix houses the Hsp60 chaperonin system, while both the matrix and intermembrane space contain specialized Hsp70 isoforms.

Mitochondrial Hsp60 (HSPD1) Structure and Function: The Hsp60 chaperonin forms a large double-ring complex with a central folding cavity that provides an isolated environment for protein folding. Unlike Hsp70, which primarily binds extended hydrophobic segments, Hsp60 encapsulates entire folding intermediates, preventing aggregation during the folding process [42]. Hsp60 deficiency disrupts the mitochondrial matrix proteome and has been shown to dysregulates cholesterol synthesis, demonstrating its essential role in mitochondrial function and metabolism [42].

Mitochondrial Hsp70 System: Mitochondrial Hsp70 (mtHsp70) plays distinct roles in the matrix, including:

- Protein import: mtHsp70 is essential for the import of nuclear-encoded proteins through the TIM complex, using ATP-dependent binding to pull precursors into the matrix.

- Folding of matrix proteins: Once imported, mtHsp70 assists in the folding of proteins in collaboration with the Hsp60/Hsp10 system.

- Proteostasis maintenance: mtHsp70 works with mitochondrial proteases to ensure degradation of misfolded proteins.

Integration with Mitochondrial Quality Control: Mitochondrial chaperones are integral components of the mitochondrial quality control (MQC) system, which includes mitochondrial dynamics (fusion and fission), mitophagy, and proteostasis [43]. This system maintains a healthy mitochondrial population through:

- Protein quality control: Molecular chaperones like HSP70 and HSP90 assist in protein folding, while degradation systems including Lon and ClPXP proteases remove misfolded or damaged proteins [44].

- Coordination with dynamics: Mitochondrial fusion allows content mixing, complementing chaperone function by enabling functional complementation between damaged mitochondria [43].

- Mitophagy regulation: When chaperones cannot rescue damaged proteins, the MQC system triggers mitophagy to remove severely damaged mitochondria [43].

Table 2: Mitochondrial Chaperone Systems and Their Functions

| Chaperone | Location | Complex Structure | Primary Functions | Associated Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp60 (HSPD1) | Matrix | Tetradecameric double-ring | Folding of matrix proteins, metabolic regulation | Neurodegeneration, myelination defects |

| mtHsp70 (HSPA9) | Matrix | Monomeric with co-chaperones | Protein import, folding, iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis | Myelodysplastic syndromes |