Evolution-Guided Atomistic Design: The Next Frontier in Protein Optimization and Therapeutic Development

This article explores the transformative methodology of evolution-guided atomistic design, a powerful computational strategy that synergizes analysis of natural evolutionary sequences with atomic-level physics-based calculations to optimize protein stability and...

Evolution-Guided Atomistic Design: The Next Frontier in Protein Optimization and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative methodology of evolution-guided atomistic design, a powerful computational strategy that synergizes analysis of natural evolutionary sequences with atomic-level physics-based calculations to optimize protein stability and function. We detail its foundational principles, which address the core challenge of negative design by leveraging evolutionary filters, and examine its successful applications in creating stable vaccine immunogens, enhancing genome editors like IscB, and designing therapeutic mini-proteins. The article further investigates the integration of machine learning for multi-parameter optimization, addresses common troubleshooting challenges, and validates the approach through comparative case studies, highlighting its profound impact on accelerating the development of biologics, enzymes, and gene therapies.

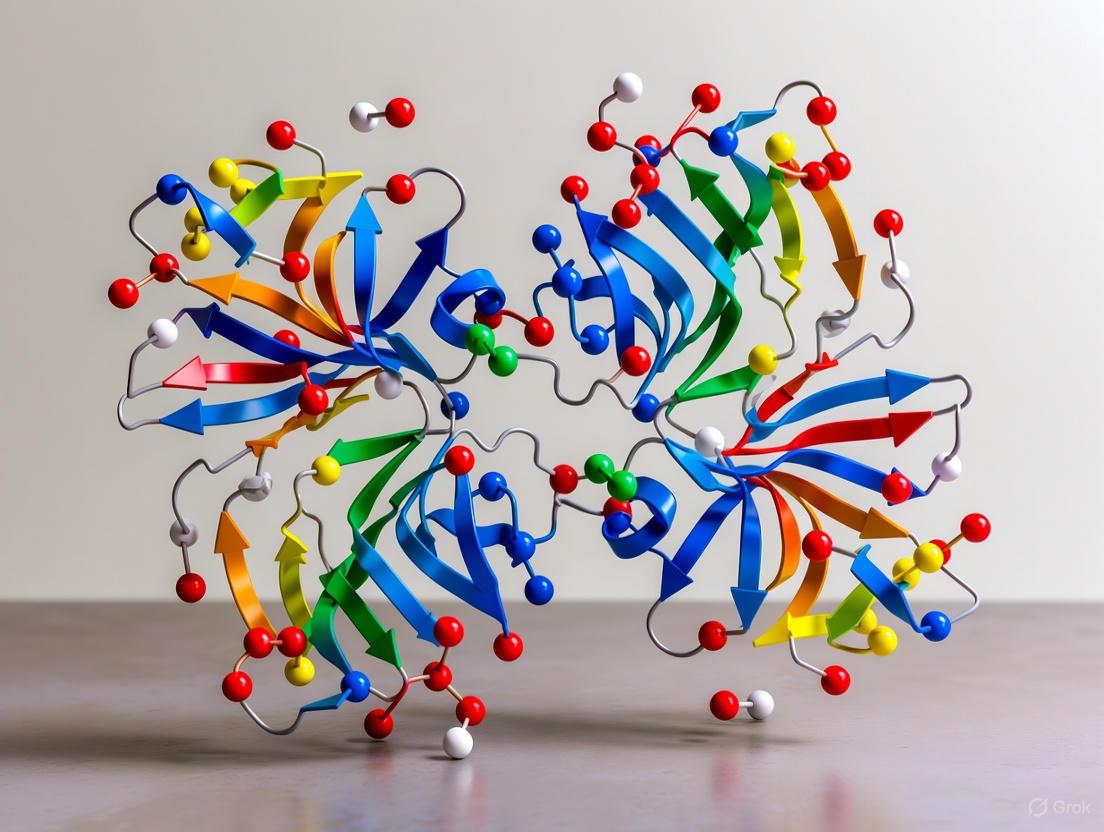

The Principles of Evolution-Guided Atomistic Design: Bridging Natural Selection and Computational Precision

The inverse function problem in protein science represents the formidable challenge of designing amino acid sequences that fold into specific three-dimensional structures to perform desired activities, a task inverse to predicting structure from sequence. Framed within the research paradigm of evolution-guided atomistic design, this problem seeks to leverage information from natural protein evolution to inform computational models, enabling the creation of novel proteins with optimized functions for therapeutic and diagnostic applications [1]. This approach is revolutionizing drug development by providing a rational framework for designing high-precision molecular tools, such as the mini-binders for cancer imaging discussed in this protocol.

The following application notes detail the experimental and computational methodologies for tackling the inverse function problem, providing a structured framework for researchers to design, validate, and characterize novel protein activities. The protocols are designed with an emphasis on evolutionary principles and atomistic precision, ensuring that designed proteins are not only functional but also exhibit biophysical properties suitable for therapeutic development.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential research reagents and computational tools for inverse function protein design.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| EvoDesign [2] [3] | Evolution-guided sequence design protocol | Generates sequence decoys using Monte Carlo simulations guided by evolutionary profiles and knowledge-based energy terms. |

| SPDesign [4] | Deep learning-based sequence design | Utilizes structural sequence profiles and graph neural networks for sequence prediction; achieves 67.05% recovery on CATH 4.2. |

| ProteinMPNN [5] [6] | Inverse folding neural network | An autoregressive message-passing neural network for designing sequences for a given protein backbone structure. |

| AFDistill [7] | Fast, distilled structure consistency scorer | Predicts AlphaFold's pLDDT/pTM scores to evaluate structural consistency of designed sequences without full structure prediction. |

| I-TASSER [2] | Protein structure prediction suite | Assesses folding integrity of designed sequences via threading and assembly simulations. |

| EvoEF2 [2] | Energy-based protein design force field | Optimizes and evaluates the binding affinity and stability of designed protein sequences. |

| HER2 Extracellular Domain (ECD) [2] | Target antigen for binding assays | Recombinant biotinylated protein for validating binder affinity via surface plasmon resonance and flow cytometry. |

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Design Methods

Evaluating the success of computational design strategies requires a multi-faceted approach, analyzing metrics from sequence recovery to functional efficacy.

Table 2: Performance metrics of leading protein sequence design methods on benchmark tests.

| Design Method | Core Principle | Sequence Recovery (CATH 4.2) | Key Functional Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPDesign [4] | Structural sequence profile & GNN | 67.05% | High accuracy in orphan and de novo benchmarks |

| LM-Design [4] | Language model with structural adapter | ~55.65% (inferred) | Leverages pre-trained protein language models |

| ProteinMPNN [4] | Message-passing neural network | ~51.16% (inferred) | Fast, good for complexes and fixed-chain design |

| GVP (Baseline) [7] | Geometric Vector Perceptron GNN | 38.6% | Incorporates geometric features natively |

| GVP + SC (AFDistill) [7] | Structure-consistency regularization | 40.8% - 42.8% | Up to 45% higher sequence diversity |

| EnhancedMPNN (ResiDPO) [6] | Designability Preference Optimization | N/A (New metric) | ~3x higher designability success for enzymes |

Experimental Protocols for Design and Validation

Protocol: Evolution-Guided Mini-Protein Design (EvoDesign)

This protocol outlines the process for designing a novel mini-protein binder against a therapeutic target, following the methodology that produced the high-contrast HER2 imaging agent, BindHer [2] [3].

I. Materials

- Target protein structure (e.g., HER2 ECD, PDB ID: 3MZW)

- EvoDesign software suite [2] [3]

- High-performance computing cluster

- In-house or public protein structure database (e.g., PDB, AlphaFold DB)

II. Procedure

- Template Identification and MSA Construction

- Perform a structural alignment screen of the PDB using TM-align with the target structure as the query to identify structurally analogous scaffolds (e.g., 159 scaffolds were identified for HER2) [2].

- Construct a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) from the identified structural analogs.

Monte Carlo Sequence Simulation

- Input the target structure and the evolutionary profile derived from the MSA into EvoDesign.

- Run replica-exchange Monte Carlo (REMC) simulations guided by a knowledge-based energy function to generate a large set (e.g., 500) of low-energy sequence decoys [2].

Druggability Optimization Funnel

- Binding Affinity Assessment: Score each designed sequence using EvoEF2 to predict its binding energy to the target.

- Folding Integrity Validation: Model the structure of each designed sequence using I-TASSER. Filter out designs with high Cα RMSD from the target backbone.

- Spatial Aggregation Propensity (SAP) Evaluation: Use a high-throughput method (e.g., CIS-RR side-chain packing) to calculate the SAP score, selecting designs with low hydrophobicity and high solubility [2].

- Apply Wynn statistics to identify consensus sequences from the top-performing designs across all three metrics.

Protocol: Functional Validation of Designed Mini-Binders

This protocol details the experimental validation of computationally designed protein sequences, specifically for binding affinity, stability, and in vivo imaging performance [2].

I. Materials

- Purified designed proteins and positive control (e.g., ABY-025)

- Yeast surface display vector

- Biotinylated target antigen (e.g., HER2 ECD)

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) system (e.g., Biacore)

- Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) instrument (e.g., UNcle)

- Circular Dichroism (CD) spectropolarimeter

- Radiolabeling kits (e.g., for ⁹⁹ᵐTc, ⁶⁸Ga, ¹⁸F)

- Animal model for disease (e.g., HER2-positive breast cancer mouse model)

- SPECT/CT or PET/CT imaging system

II. Procedure

- Initial Binding Affinity Screening via Yeast Surface Display

- Clone the designed sequences into a yeast surface-display vector with a C-Myc tag for detection.

- Induce expression of the designed binders on the yeast surface.

- Incubate yeast cells with biotinylated HER2 ECD, followed by staining with fluorescent streptavidin and anti-C-Myc antibody.

- Analyze binding via flow cytometry. Designs showing strong fluorescence shift (e.g., Design.01-05) are selected for further analysis [2].

Biophysical Characterization

- Expression and Purification: Express the selected designs in E. coli and purify using Ni²⁺-NTA chromatography. Aim for >95% purity and soluble yields >200 mg/L [2].

- Binding Kinetics (SPR): Immobilize HER2 ECD on an SPR chip. Flow purified designs at various concentrations. Calculate the dissociation constant (KD); successful designs exhibit KD in the low nM range (0.191-1.99 nmol/L) [2].

- Thermal Stability (DSF): Subject proteins to a thermal denaturation gradient. Determine the melting temperature (Tm). Superior designs (e.g., Design.01, .04, .05) show Tm values higher than the positive control [2].

- Secondary Structure (CD): Acquire CD spectra to confirm alpha-helical content. Perform thermal stress tests (e.g., 100°C for various durations) to assess structural robustness [2].

- Proteolytic Stability: Incubate proteins with a trypsin gradient (0.01-10 μmol/L). Analyze by SDS-PAGE; stable designs (e.g., Design.05) show minimal degradation at high trypsin concentrations [2].

In Vivo Imaging and Biodistribution

- Radiolabel the designed mini-protein (e.g., BindHer) and the control (ABY-025) with radionuclides such as ⁹⁹ᵐTc, ⁶⁸Ga, or ¹⁸F.

- Administer the radiolabeled proteins intravenously to HER2-positive breast cancer mouse models.

- Acquire SPECT or PET/CT images at multiple time points. Successful designs demonstrate high tumor uptake and significantly reduced non-specific liver absorption compared to the control [2].

Advanced Computational Design Workflows

Protocol: Designability-Optimized Inverse Folding (ResiDPO)

This protocol describes fine-tuning an inverse folding model with Residue-level Designability Preference Optimization (ResiDPO) to directly maximize the probability that designed sequences fold into the target structure, a critical improvement over standard sequence recovery objectives [6].

I. Materials

- Pre-trained inverse folding model (e.g., LigandMPNN)

- Dataset of protein backbones and sequences for fine-tuning

- AlphaFold2 software for pLDDT calculation

- High-performance GPU computing resources

II. Procedure

- Generate Preference Dataset

- For a set of backbone structures (x), use the base model (e.g., LigandMPNN) to generate candidate sequences (y).

- For each (x, y) pair, use AlphaFold2 to predict the structure of y and obtain the per-residue pLDDT scores, which serve as a proxy for local designability.

- For each backbone, rank the generated sequences by their overall designability (e.g., average pLDDT) to create preferred (yw) and dispreferred (yl) pairs [6].

- Fine-Tune with ResiDPO Loss

- The key innovation of ResiDPO is the decoupled residue-level loss function. It separately optimizes residues with low pLDDT (prioritizing the preference reward) and residues with high pLDDT and high model confidence (prioritizing regularization to prevent forgetting) [6].

- Implement the ResiDPO loss function and fine-tune the base model on the preference dataset.

- The resulting model (e.g., EnhancedMPNN) shows a nearly 3-fold increase in design success rate on challenging enzyme design benchmarks compared to the base model [6].

Protocol: Structure-Consistency Regularized Design (AFDistill)

This protocol uses a distilled version of AlphaFold to provide a fast, differentiable structure consistency score during inverse model training, enhancing the structural integrity of designed sequences [7].

I. Materials

- AFDistill model (pre-trained)

- Inverse folding model (e.g., GVP)

- CATH 4.2 or similar dataset for training

II. Procedure

- Knowledge Distillation from AlphaFold

- Train the AFDistill model to predict AlphaFold's pTM or pLDDT scores directly from the protein sequence, bypassing the need for slow structure prediction [7].

- Regularized Model Training

- During training of the inverse folding model (e.g., GVP), add an auxiliary loss term: the Structure Consistency (SC) loss.

- The SC loss is computed by comparing the AFDistill-predicted score for a generated sequence against a high target score (or the score of the native sequence). This penalizes sequences predicted to fold poorly [7].

- The total loss is:

L_total = L_recovery + λ * L_SC, where λ is a weighting hyperparameter. - This approach yields a 1-3% improvement in sequence recovery and up to a 45% improvement in sequence diversity while maintaining high structural accuracy (TM-score) [7].

The overarching goal of computational protein design is to achieve complete control over protein structure and function, particularly for large proteins with complex folds that defy purely atomistic calculations. Evolution-guided atomistic design has emerged as a powerful strategy that combines information from the evolutionary history of protein families with physics-based atomistic calculations to overcome these challenges. This approach uses natural sequence diversity to infer structural and sequence features that are evolutionarily tolerated, thereby guiding Rosetta atomistic design calculations in the search for novel proteins with desired functions [1] [8]. The natural evolutionary record effectively implements aspects of negative design by eliminating sequences prone to misfolding and aggregation, while the atomistic calculations focus on positive design to stabilize the desired native state within this evolutionarily refined sequence space [9].

This design framework addresses what we term "the dual challenge" in protein engineering: the simultaneous requirement to stabilize the native state (positive design) while destabilizing misfolded and aggregated states (negative design). According to the Thermodynamic Hypothesis, a protein's native state must have significantly lower energy than all alternative states, including misfolded and unfolded conformations, for reliable folding and function [9]. While positive design strengthens favorable interactions within the native structure, negative design introduces strategic repulsive interactions in non-native conformations that might otherwise compete with the native fold [10] [11]. The following sections detail the principles, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks for implementing this dual design strategy, with a focus on practical applications for researchers and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Principles

Physical Basis of Positive and Negative Design

Protein stability depends on the energy gap between the native state and all non-native conformations. Positive design refers to introducing favorable interactions between residues that are in contact in the native state, thereby stabilizing the desired fold. In contrast, negative design introduces unfavorable interactions between residues that come into contact in non-native conformations, thereby destabilizing misfolded states [10]. The balance between these strategies is influenced by a protein's structural properties, particularly its average contact-frequency—defined as the fraction of states in a protein's conformational ensemble where any given pair of residues is in contact [10].

Research on lattice models and natural proteins reveals that the choice between positive and negative design strategies depends on structural characteristics. Proteins with low average contact-frequencies preferentially utilize positive design, as the interactions that stabilize their native state are rarely found in non-native states. Conversely, proteins with high contact-frequencies (such as intrinsically disordered proteins or those requiring chaperonins for folding) rely more heavily on negative design, since the interactions stabilizing their native state commonly appear in non-native conformations and must be counterbalanced [10].

Evolution's Design Principles in Natural Proteomes

Analysis of natural proteomes reveals how evolution has balanced positive and negative design across different environmental conditions. Thermophilic organisms, which thrive at high temperatures, exhibit a characteristic "from both ends of the hydrophobicity scale" trend in their amino acid compositions. Their proteomes show increased fractions of both hydrophobic residues (e.g., Ile, Val, Leu, Phe) and charged residues (e.g., Asp, Glu, Lys, Arg) at the expense of polar residues [11].

In this evolutionary strategy, hydrophobic residues primarily contribute to positive design by stabilizing the native core, while charged residues contribute to negative design through strategic repulsive interactions in misfolded conformations. This combination creates a wider energy gap between native and non-native states, enhancing stability at elevated temperatures [11]. This principle has been validated through lattice model simulations and comparative proteomics, providing a blueprint for designing thermostable proteins.

Table 1: Key Principles of Positive and Negative Design

| Design Principle | Objective | Molecular Strategy | Observed in Natural Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Design | Stabilize native state | Introduce favorable interactions between residues in contact in native structure | Increased hydrophobic residues in thermophiles |

| Negative Design | Destabilize non-native states | Introduce repulsive interactions between residues that contact in misfolded states | Increased charged residues in thermophiles |

| Contact-Frequency Dependence | Optimize design strategy based on structure | Use negative design when native interactions commonly appear in non-native states | Proteins with high contact-frequencies show more correlated mutations |

| Evolution-Guided Filtering | Reduce aggregation risk | Incorporate only evolutionarily observed variations | Natural homologs provide constraints on viable sequence space |

Quantitative Analysis of Design Principles

Trade-offs Between Positive and Negative Design

Lattice model studies have quantified the fundamental trade-off between positive and negative design. Research demonstrates an almost perfect negative correlation (r = -0.96, P-value<0.0001) between the contributions of positive and negative design to stability across different protein folds [10]. This strong trade-off indicates that structural properties largely determine which strategy will be most effective for stabilizing a given protein.

The average contact-frequency of a fold directly influences this balance. Native states with very high average contact-frequencies show minimal gains from positive design, instead relying predominantly on negative design. Conversely, native states with very low average contact-frequencies benefit mainly from positive design, with negative design contributing little to their stability [10]. This relationship has important implications for choosing design strategies based on a target protein's structural characteristics.

Correlated Mutations as Signature of Negative Design

Negative design often requires maintaining specific repulsive interactions between residues that are not in contact in the native state but may interact in misfolded conformations. This constraint can lead to correlated mutations—where mutations at one site are accompanied by compensatory mutations at a distant site—even when those residues are far apart in the native structure [11].

Proteins with high contact-frequencies (such as disordered proteins and chaperonin-dependent proteins) show stronger correlated mutations compared to those with typical contact-frequencies [10]. This pattern suggests that negative design pressures shape evolutionary sequences, particularly for proteins that are inherently prone to misfolding. Analysis of correlated mutations in natural protein sequences can therefore help identify positions where negative design constraints have operated, providing guidance for computational design.

Table 2: Quantitative Relationships in Protein Design Strategies

| Structural Property | Impact on Positive Design | Impact on Negative Design | Correlation with Design Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Contact-Frequency | Strongly favored | Minimally used | r = -0.608 with |

| High Contact-Frequency | Minimally effective | Strongly favored | r = 0.639 with |

| Thermophilic Adaptation | Increased hydrophobic residues | Increased charged residues | IVYWREL index predicts OGT (R=0.93) [11] |

| Correlated Mutations | Associated with native contacts | Associated with non-native contacts | Higher in proteins with folding difficulties [10] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Evolution-Guided Atomistic Design Protocol

Purpose: To design stable, functional protein variants by combining evolutionary constraints with atomistic calculations, thereby addressing both positive and negative design challenges.

Workflow:

Sequence Homolog Collection

- Identify natural homologs of the target protein using BLAST or HMMER searches against non-redundant databases

- Curate a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) with diverse representatives covering phylogenetic diversity

- Critical Step: Ensure sufficient sequence diversity while maintaining structural coverage of the target

Evolutionary Analysis

- Calculate position-specific conservation scores from the MSA

- Identify co-evolving residues using tools like EVcouplings or plmDCA

- Output: Map of evolutionarily tolerated substitutions and correlated mutation networks

Structure Preparation

- Obtain experimental structure or generate high-quality homology model

- Identify native contacts and potential frustration points in the fold

- Note: For proteins without structures, use AlphaFold2 predictions with confidence metrics

Sequence Space Filtering

- Filter design candidates to include only variations observed in natural homologs

- This implements negative design by excluding sequences prone to misfolding

- Result: Sequence space reduced by several orders of magnitude

Atomistic Design Calculations

- Use Rosetta or similar software to optimize sequences within the filtered space

- Focus on stabilizing native state interactions (positive design)

- Scoring: Combine physical energy terms with evolutionary conservation metrics

Experimental Validation

Diagram 1: Evolution-guided atomistic design workflow. This protocol combines evolutionary constraints with atomistic calculations to balance positive and negative design.

Assessing Misfolding Propensity and Aggregation

Purpose: To evaluate designed proteins for resistance to misfolding and aggregation, addressing negative design outcomes.

Workflow:

Solubility and Expression Analysis

- Express designs in appropriate heterologous system (typically E. coli)

- Separate soluble and insoluble fractions by centrifugation

- Quantify yield in soluble fraction by SDS-PAGE or Western blot

- Benchmark: Compare to wild-type protein and known stable controls

Thermal Stability Assay

- Use differential scanning fluorimetry (thermal shift assay)

- Monitor fluorescence of environment-sensitive dyes (e.g., SYPRO Orange)

- Calculate Tm (melting temperature) from denaturation curve

- Advanced: Determine ΔG of unfolding and Tm by circular dichroism or DSC

Aggregation Propensity Screening

- Incubate proteins under accelerated stress conditions (elevated temperature)

- Monitor aggregation by dynamic light scattering or static light scattering

- Assess amyloid formation using thioflavin T fluorescence

- Validation: Test resistance to aggregation over 24-72 hours

Proteostatic Compatibility

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Design Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Design Validation | Protocol Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Systems | E. coli BL21(DE3), insect cell systems, mammalian HEK293 | Heterologous production of designed variants | Solubility and yield assessment |

| Stability Assay Reagents | SYPRO Orange, thioflavin T, Congo red | Probe thermal stability and amyloid formation | Thermal shift assays, aggregation monitoring |

| Proteomics Tools | 2DDB software platform, DIA-NN, MaxQuant | Manage and analyze quantitative proteomics data | Identification of aggregation-prone variants |

| Chromatography Resins | Ni-NTA agarose (His-tag), streptavidin beads (biotin tag) | Purification of designed proteins | Assessment of folding and monodispersity |

| Structural Biology | Cryo-EM instruments, ssNMR spectrometers | High-resolution structure determination | Validation of designed vs. actual structures |

| Design Software | Rosetta, AlphaFold2, EVcouplings | Computational design and analysis | Implementation of evolution-guided strategies |

Case Study: Engineering Thermostable Malaria Vaccine Candidate

Application to RH5 Malaria Antigen

The protein RH5 from Plasmodium falciparum is a leading malaria vaccine candidate but suffers from marginal stability (denaturation at ~40°C) and poor expression yields in cost-effective systems. Researchers applied evolution-guided atomistic design to enhance its stability while maintaining immunogenicity [9].

The design process began with collecting RH5 homologs from apicomplexan parasites to define evolutionarily allowed sequence variations. Analysis revealed positions with strong conservation patterns and co-evolutionary networks. Atomistic design calculations within this constrained sequence space identified mutations that improved hydrophobic packing (positive design) and introduced strategic charged residues in surface loops (negative design) [9].

The resulting designed variant exhibited dramatically improved properties:

- Thermal stability: Increased denaturation temperature by nearly 15°C

- Expression: Robust production in E. coli (versus previous requirement for insect cells)

- Immunogenicity: Maintained protective epitopes and antigenicity

- Developability: Improved shelf-life and resistance to aggregation

This case demonstrates how the dual design approach can overcome stability and expression bottlenecks for therapeutic proteins, particularly for global health applications where cost and stability are critical considerations.

Protocol for Stability Enhancement of Vaccine Antigens

Purpose: To enhance thermal stability and expression of vaccine immunogens while maintaining immunogenic properties.

Workflow:

Epitope Mapping

- Identify conserved protective epitopes through structural biology or mutagenesis

- Define constrained regions where mutations are prohibited

- Method: X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, or hydrogen-deuterium exchange MS

Homolog Identification

- Focus on pathogenic organisms within the same family

- Balance diversity with relevance to target organism

- Database: NCBI non-redundant database, specialized pathogen databases

Stability Design

- Use FoldX or Rosetta to predict stability effects of mutations

- Prioritize mutations with predicted stability gains >1 kcal/mol

- Filter: Exclude mutations in epitope regions

Multi-parameter Optimization

- Select designs with optimal stability and epitope preservation

- Use structural analysis to verify native state stabilization

- Output: 5-10 lead designs for experimental testing

Immunogenicity Validation

- Test binding to conformation-sensitive antibodies

- Assess immunogenicity in animal models

- Compare to wild-type antigen as benchmark [9]

Diagram 2: Vaccine antigen stabilization workflow. This protocol enhances stability while preserving immunogenic epitopes.

Analytical Methods for Assessing Design Outcomes

Quantifying Positive and Negative Design Contributions

Advanced analytical methods can dissect the individual contributions of positive and negative design to protein stability. The double-mutant cycle (DMC) method provides a powerful approach to quantify interaction energies between residue pairs in both native and non-native contexts [10].

Double-Mutant Cycle Analysis Protocol:

Generate Mutant Series

- Create single mutants at positions i and j (Ai and Aj)

- Create double mutant (Aij)

- Ensure all variants express and fold properly

Measure Stability Effects

- Determine ΔG of unfolding for each variant

- Use thermal denaturation or chemical denaturation

- Precision: Replicate measurements to achieve <0.1 kcal/mol error

Calculate Coupling Energies

- Compute ΔΔGint = ΔGij - ΔGi - ΔGj + ΔGwild-type

- This represents the interaction energy between positions i and j

Classify Interactions

- Native contacts with negative ΔΔGint contribute to positive design

- Non-native contacts with positive ΔΔGint contribute to negative design

- Statistical analysis: Compare means across different contact types [10]

Correlated Mutation Analysis

Purpose: To identify residue pairs involved in negative design constraints through evolutionary analysis.

Workflow:

Construct High-Quality MSA

- Curate diverse but related sequences

- Ensure sufficient coverage and quality

- Minimum: 100 effective sequences for statistical power

Calculate Correlated Mutations

- Use maximum entropy models (plmDCA) or direct coupling analysis

- Account for phylogenetic bias and sampling noise

- Output: Scores for all residue pairs indicating coupling strength

Map to Structure

- Identify correlated pairs distant in native structure

- Test if these positions contact in misfolded models

- Interpretation: Long-range correlated mutations suggest negative design

Experimental Validation

The integration of positive and negative design principles within an evolution-guided framework represents a significant advance in computational protein design. By leveraging natural evolutionary information to constrain sequence space and implement negative design, then applying atomistic calculations to optimize native state stability, this approach addresses the fundamental challenge of designing proteins that not fold correctly but also avoid misfolding and aggregation.

The methods and protocols outlined here provide researchers with practical tools to implement this dual design strategy for various applications, from enzyme engineering to therapeutic protein development. As protein design methodologies continue to advance—particularly with the integration of deep learning approaches like AlphaFold2 and protein language models—the precision and scope of design will further improve. However, the fundamental principles of balancing positive and negative design will remain essential for creating functional, robust proteins that meet the challenges of research and therapeutic applications.

Future directions in the field include developing more sophisticated methods for predicting and designing against aggregation, expanding design capabilities to membrane proteins and larger complexes, and improving multi-property optimization to simultaneously address stability, activity, and specificity. As these methods mature, completely computational design of proteins with custom-tailored properties will become increasingly routine, accelerating progress in biotechnology and therapeutic development.

In the field of protein engineering, the sequence diversity generated through millions of years of natural evolution provides a rich resource for designing proteins with enhanced or novel functions. Natural sequence diversity serves as a sophisticated filter that identifies functional variants while excluding deleterious mutations already weeded out by evolutionary pressure [14]. This approach stands in contrast to purely random mutagenesis methods, offering a higher probability of discovering functional proteins with improved stability and activity.

The core premise of harnessing evolutionary wisdom lies in the observation that modern sequence diversity represents sequences that have already been deemed 'fit to survive' [14]. This review details practical applications and protocols for leveraging this evolutionary information in protein optimization research, particularly within the context of evolution-guided atomistic design. We present a structured framework for implementing these approaches, complete with quantitative comparisons and experimental workflows.

Evolutionary Approaches and Their Applications

Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary Methods

Table 1: Key Approaches in Evolution-Guided Protein Design

| Approach | Methodology | Use of Sequence Information | Functional Information Content | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Shuffling | Recombination among extant sequences via PCR fragmentation and reassembly [14] | Modern sequence diversity only | Low | Enzyme engineering, herbicide resistance [14] |

| Consensus Design | Deriving the most common amino acid at each position across homologs [14] | Modern sequence diversity only | Moderate | Thermostability enhancement (e.g., fungal phytase, β-lactamase) [14] |

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) | Computational inference and experimental resurrection of ancestral sequences [14] | Sequence history and diversity | Moderate | Thermostable enzymes, understanding functional diversification [14] |

| Ancestral Mutation Method (AMM) | Incorporating ancestral residues into modern protein scaffolds [14] | Single modern sequence + subset of ancestral residues | High | Thermostability improvement while maintaining modern function [14] |

| Natural Diversity Mining | Identifying and characterizing unannotated protein families from genomic data [15] | Global natural sequence diversity | Variable | Discovery of new protein folds and functions (e.g., β-flower fold, TumE-TumA system) [15] |

| Continuous Evolution (T7-ORACLE) | Orthogonal replication system in E. coli with error-prone polymerase [16] [17] | Directed evolution accelerated by 100,000x mutation rate | Not specified | Antibody engineering, therapeutic enzyme optimization, protease design [16] [17] |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Performance Outcomes of Evolutionary Protein Design Methods

| Method | Documented Improvement | Timeframe | Library Size Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Shuffling | 4 orders of magnitude activity increase in glyphosate acetyltransferase over 11 rounds [14] | Weeks to months | Very large libraries, can be resource-limited [14] |

| Consensus Design | 15-22°C increase in thermostability of fungal phytase [14] | Direct construction | Can be as small as a single variant [14] |

| Ancestral Mutation Method | Multiple variants with increased thermostability and activity in β-amylase [14] | Direct construction | Small, focused libraries with high functional content [14] |

| T7-ORACLE | Evolved TEM-1 β-lactamase resisting antibiotic levels 5,000x higher than wild-type [16] | Less than one week | Continuous evolution without manual intervention [16] [17] |

| DeepSCFold | 11.6% and 10.3% improvement in TM-score over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 in CASP15 [18] | Computational prediction | Leverages deep learning on sequence-derived structural complementarity [18] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Consensus Protein Design

Objective: Enhance thermostability of a target protein using consensus design.

Materials:

- Multiple sequence alignment of homologous proteins

- Molecular biology reagents for gene synthesis

- Protein expression system

- Thermostability assay reagents

Procedure:

- Sequence Collection and Alignment: Collect a diverse set of homologous protein sequences (minimum 10-15 sequences recommended). Perform multiple sequence alignment using tools such as Clustal Omega or MAFFT.

- Consensus Calculation: At each position in the alignment, identify the most frequently occurring amino acid. For positions with equal frequency, choose the amino acid with higher physicochemical similarity to other options.

- Gene Synthesis: Synthesize the full-length consensus gene using commercial gene synthesis services.

- Protein Expression and Purification: Express and purify the consensus protein using standard protocols appropriate for your expression system.

- Functional Validation:

- Assess thermostability by measuring residual activity after incubation at elevated temperatures.

- Compare catalytic activity to wild-type protein under standard conditions.

- Determine melting temperature (Tm) using differential scanning fluorimetry.

Troubleshooting: If consensus protein fails to express or fold properly, consider constructing a hybrid approach where only a subset of positions (e.g., those with >70% conservation) are converted to consensus.

Protocol 2: T7-ORACLE Continuous Evolution

Objective: Rapidly evolve a protein with improved function using continuous evolution system.

Materials:

- T7-ORACLE E. coli strain

- Plasmid vector compatible with T7-ORACLE system

- Selective antibiotics

- Appropriate selection pressure

Procedure:

- Gene Cloning: Clone your target gene into the T7-ORACLE compatible plasmid vector.

- Transformation: Transform the plasmid into the T7-ORACLE E. coli strain.

- Continuous Evolution Culture:

- Inoculate transformed bacteria into appropriate medium with selective antibiotics.

- Apply appropriate selection pressure (e.g., antibiotic for resistance genes, substrate for enzymes).

- Culture for 3-7 days, periodically increasing selection pressure as evolution progresses.

- Variant Isolation:

- After evolution period, plate cultures on selective medium.

- Isolate individual colonies for sequencing and functional characterization.

- Characterization:

- Sequence evolved variants to identify mutations.

- Purify proteins and characterize functional improvements.

Key Considerations: The T7-ORACLE system introduces mutations at a rate 100,000 times higher than normal without damaging the host cells, enabling rapid evolution [16] [17]. Selection pressure should be carefully calibrated to maintain cell viability while driving evolution.

Visualization of Methodologies

Evolutionary Protein Design Workflow

Natural Sequence Diversity Utilization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Evolution-Guided Protein Design

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Databases | Provides evolutionary sequence diversity for analysis | Consensus design, ancestral sequence reconstruction [14] |

| T7-ORACLE E. coli System | Host for continuous evolution with orthogonal replication | Rapid directed evolution of therapeutic proteins [16] [17] |

| Error-Prone T7 DNA Polymerase | Generates mutations at 100,000x normal rate in T7-ORACLE | Introducing diversity in continuous evolution systems [16] |

| AlphaFold Database | Provides predicted structures for functionally dark proteins | Mining unannotated protein families for new folds [15] |

| DeepSCFold Pipeline | Predicts protein-protein structural similarity from sequence | Modeling protein complex structures [18] |

| RosettaEvolutionaryLigand (REvoLd) | Evolutionary algorithm for ultra-large library screening | Drug discovery in make-on-demand chemical spaces [19] |

Natural sequence diversity provides an powerful filter for guiding protein engineering efforts toward functional and stable variants. The methods outlined here—from consensus design to continuous evolution systems—offer researchers a toolkit for exploiting evolutionary wisdom in protein optimization. As structural prediction algorithms improve and our ability to mine natural diversity expands, these evolution-guided approaches will play an increasingly central role in atomistic protein design for therapeutic and industrial applications.

The Thermodynamic Hypothesis and Its Role in Computational Protein Design

The Thermodynamic Hypothesis, first articulated by Anfinsen, posits that the native functional state of a protein corresponds to its global minimum free energy state under physiological conditions [20]. This principle serves as a foundational pillar for computational protein design, enabling researchers to predict and engineer protein structures by identifying amino acid sequences that fold into stable, pre-defined three-dimensional conformations. In modern practice, this hypothesis is implemented through sophisticated computational frameworks that calculate energy functions to distinguish optimal native states from a vast constellation of alternative conformations [9]. The integration of this physical principle with evolutionary guidance has created a powerful paradigm for designing proteins with enhanced stability, novel functions, and therapeutic potential, forming the core of evolution-guided atomistic design strategies [1] [9].

Theoretical Foundation

The Thermodynamic Hypothesis and the Energy Landscape

The Thermodynamic Hypothesis establishes that a protein's native state is thermodynamically favored, but the pathway to this state is governed by its energy landscape [20]. A foldable protein exhibits a "funnel-shaped" landscape where the native state is separated from non-native states by a sufficient energy gap [20]. This landscape is not static; during evolution, random mutations are accepted if they do not compromise folding or function. Conversely, mutations that destabilize deep, alternative energy minima are favorably selected, thereby reinforcing the native state as the global free energy minimum over evolutionary timescales—even when folding is under kinetic control [20].

Table 1: Key Concepts in the Energy Landscape of Protein Folding

| Concept | Description | Design Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Gap | The energy separation between the native state and the nearest non-native states [20]. | A larger gap promotes robust folding and stability. Design strategies aim to maximize this gap [9]. |

| Folding Funnel | A conceptual landscape directing the folding protein toward the native state without a strictly defined pathway [20]. | Designs should exhibit a smooth, funnel-like landscape to minimize kinetic traps. |

| Negative Design | The computational strategy of destabilizing non-native, misfolded, or aggregated states [9]. | Essential for ensuring the unique foldability of a designed protein and preventing off-target interactions. |

The Challenge of Negative Design

A central challenge in computational protein design is negative design. While the desired native state is known and can be optimized ("positive design"), the vast ensemble of competing unfolded and misfolded states is typically unknown [9]. Failing to sufficiently destabilize these alternative states can result in designed proteins that aggregate, misfold, or exhibit conformational flexibility [9]. Evolution-guided strategies help address this by leveraging the information in natural protein sequences, which have already been pre-selected by evolution to avoid problematic sequences prone to misfolding [9].

Computational Protocols for Stability Design and De Novo Creation

This section details practical methodologies for applying the Thermodynamic Hypothesis through two complementary approaches: optimizing existing proteins and creating new ones from scratch.

Protocol 1: Evolution-Guided Stability Design

This protocol enhances the stability and heterologous expression of proteins, crucial for research and therapeutics [9].

1. Objective: Stabilize a target protein without altering its native structure or function. 2. Input Requirements: A high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein and a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of homologous sequences. 3. Procedural Steps: - Step 1: Sequence Analysis. Analyze the MSA to determine the natural amino acid diversity at each position. Identify and filter out very rare mutations, focusing the design space on evolutionarily tolerated sequences [9]. - Step 2: Atomistic Design Calculation. Using the filtered sequence space, perform positive design via Rosetta or similar software. The goal is to identify a sequence that minimizes the computed free energy of the native state [1] [9]. - Step 3: In Silico Validation. Validate the designed model using structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2 or ESMFold. A successful design will have a predicted structure nearly identical to the target (backbone RMSD < 2 Å) with high confidence (pLDDT > 80, pAE < 5) [21]. - Step 4: Experimental Characterization. - Circular Dichroism (CD): Confirm secondary structure content and measure thermal stability (Tm) [22]. - Differential Scanning Calorimetry (ITC): Provides detailed thermodynamic parameters of unfolding [22]. - Functional Assays: Ensure the stabilized variant retains or improves its intended activity.

4. Application Note: This method dramatically improved the production of the malaria vaccine candidate RH5, enabling its expression in E. coli and increasing its thermal stability by nearly 15°C [9].

Protocol 2: De Novo Protein Design with RFdiffusion

This protocol generates entirely new protein structures and functions using generative AI [21].

1. Objective: Create a novel protein fold or a protein binder for a specific target. 2. Input Requirements: For unconditional generation, no input is needed. For binder design, the 3D structure of the target is required. 3. Procedural Steps: - Step 1: Structure Generation with RFdiffusion. - Initialization: Begin with random residue frames (Cα coordinates and N-Cα-C orientations). - Iterative Denoising: RFdiffusion, a diffusion model fine-tuned from RoseTTAFold, is applied for ~100 steps. At each step, the network predicts a less noisy structure, progressively refining the random input into a protein-like backbone [21]. - Conditioning (Optional): For specific tasks (e.g., binder design), the process can be conditioned on target coordinates, partial structures, or fold specifications [21]. - Step 2: Sequence Design with ProteinMPNN. For the final generated backbone, use the ProteinMPNN neural network to design a sequence that is predicted to fold into that structure. Sample multiple sequences (e.g., 8 per design) to explore sequence diversity [21]. - Step 3: In Silico Filtering. Use AlphaFold2 or ESMFold to predict the structure of the designed sequences. Select designs that meet success criteria (high confidence, low RMSD to the design model) [21]. - Step 4: Experimental Validation. - Structure Determination: Validate high-resolution structure via X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM. - Stability Analysis: Use CD spectroscopy and thermal denaturation to confirm stability. - Binding Assays: For binders, use Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or similar biophysical methods to measure affinity and specificity [22].

5. Application Note: RFdiffusion has been used to design novel protein binders against influenza hemagglutinin, with cryo-EM structures confirming near-atomic accuracy to the design model [21].

Diagram 1: Computational protein design workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Methods

Table 2: Essential Computational and Experimental Tools for Protein Design

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Rosetta | Software Suite | Performs atomistic design and energy calculations to identify low-energy sequences for a target structure [1]. |

| RFdiffusion | Software (Generative AI) | Generates novel, diverse protein backbone structures from noise or conditioned on specific inputs [21]. |

| AlphaFold2/ESMFold | Software (Structure Prediction) | Validates designed proteins by predicting the 3D structure of a designed sequence in silico [21]. |

| ProteinMPNN | Software (Sequence Design) | Designs amino acid sequences that are predicted to fold into a given protein backbone structure [21]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Biophysical Method | Measures the kinetics (kon, koff) and affinity (Kd) of protein-protein interactions in real-time without labels [22]. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrometer | Biophysical Instrument | Determines protein secondary structure and measures thermal stability by monitoring unfolding as a function of temperature [22]. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative data is vital for comparing the performance of designed proteins. The table below summarizes key metrics from seminal studies.

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Designed Protein Performance

| Design Project / System | Key Parameter Measured | Result | Comparison / Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Designed Superstable β-Proteins [23] | Unfolding Force (by MD/Spectroscopy) | > 1,000 pN | ~400% stronger than natural titin immunoglobulin domain (~250 pN) [23]. |

| Designed Superstable β-Proteins [23] | Thermal Stability | Retained structure at 150°C | Far exceeds stability of most natural mesophilic proteins. |

| RFdiffusion De Novo Monomers [21] | In Silico Success Rate (AF2 validation) | High for monomers ≤ 600 residues | Validated by high AF2 confidence (pAE < 5) and low RMSD (< 2 Å) [21]. |

| Evolution-Guided Stabilization (RH5) [9] | Thermal Melting Point (Tm) | Increase of ~15°C | Enabled expression in E. coli vs. expensive insect cells [9]. |

| Evolution-Guided Stabilization (RH5) [9] | Heterologous Expression System | Successful in E. coli | Shift from insect cell system reduces production cost [9]. |

Diagram 2: Data visualization selection guide.

From Theory to Therapy: Methodological Workflows and Real-World Applications

Evolution-guided atomistic design represents a transformative approach in modern protein science, combining the power of natural evolutionary information with precision computational modeling. This methodology addresses a fundamental challenge in computational protein design: the astronomically large space of possible sequences and conformations. By using evolutionary constraints from natural homologs, researchers can focus atomistic calculations on a highly enriched sequence subspace that is predisposed to fold correctly, thereby mitigating the risks of misfolding and aggregation [9]. This workflow, integrating ortholog screening, structural analysis, and atomistic calculation, has dramatically optimized diverse proteins including vaccine immunogens, enzymes for sustainable chemistry, and proteins with therapeutic potential [8] [9]. This Application Note provides a detailed protocol for implementing this core workflow, framed within the context of protein optimization research for drug development and biotechnology applications.

The evolution-guided atomistic design workflow operates on a key principle: natural protein sequences have been pre-optimized by evolution for proper folding and stability. The workflow begins with broad sampling of natural diversity through ortholog screening to identify functional starting points and define evolutionary constraints. This is followed by detailed structural characterization of promising candidates, and culminates in atomistic calculations to design optimized variants. This strategy effectively decomposes the complex design problem into manageable stages—negative design is implemented through evolutionary filtering of sequences, while positive design occurs through atomistic stabilization of the desired state [9].

This approach has demonstrated remarkable success across multiple applications. For instance, stability optimization methods have become sufficiently reliable to be applied to dozens of different protein families, including ones that had resisted experimental optimization strategies [9]. In therapeutic development, this workflow has been used to optimize the protein RH5 from Plasmodium falciparum, a malaria vaccine candidate, enabling robust bacterial expression and significantly enhanced thermal stability [9]. Similarly, the workflow has been applied to engineer compact RNA-guided endonucleases like IscB for improved genome editing efficiency and specificity [24].

Table 1: Key Advantages of Evolution-Guided Atomistic Design

| Advantage | Impact on Protein Engineering |

|---|---|

| Reduced Sequence Search Space | Evolutionary constraints filter out misfolding-prone sequences, reducing design space by orders of magnitude [9]. |

| Enhanced Stability | Designed variants exhibit increased thermal resistance and heterologous expression yields [9]. |

| Maintained Function | Focus on evolutionarily conserved regions helps preserve catalytic activity and specificity [24]. |

| Overcoming Marginal Stability | Enables engineering of natural proteins that are marginally stable in their native hosts [9]. |

Ortholog Screening Protocol

Objective and Principles

Ortholog screening aims to identify natural protein variants with superior baseline properties and define the sequence space compatible with proper folding and function. This step leverages the natural diversity of homologous sequences to inform which mutations are likely to be tolerated, effectively implementing aspects of negative design by eliminating rare mutations that may promote misfolding [9].

Step-by-Step Methodology

Sequence Curation and Selection

- Source homologous sequences from databases such as UniRef30, UniRef90, UniProt, and metagenomic databases (Metaclust, BFD, MGnify) [18].

- Sample diversely across protein size, taxonomic distribution, and associated structural features (e.g., guide RNA scaffold types for nucleases) [24].

- Example: In engineering IscB, researchers initially curated 144 IscBs and 6 type II-D Cas9s, followed by a second targeted set of 240 IscBs focusing on larger variants with specific insertions [24].

In Vitro Functional Screening

- Clone selected orthologs into appropriate expression vectors.

- Perform in vitro transcription-translation (IVTT) to produce proteins.

- Screen for activity and key properties (e.g., target adjacent motif preference for nucleases) [24].

- Example Metric: Use IVTT TAM screens to identify orthologs with desired binding or cleavage preferences [24].

Cellular Activity Validation

- Test orthologs showing in vitro activity in cellular systems (e.g., human cells for therapeutic proteins).

- Use pooled guides or substrates (e.g., 12 guides per ortholog for nuclease screening) to assess functionality in complex cellular environments [24].

- Example: In IscB engineering, orthologs active in vitro were tested for genome editing activity in human cells using a pool of 12 guides of 20 nt length per ortholog [24].

Hit Validation and Characterization

- Confirm activity of top candidates using individual guides or substrates across multiple target sites.

- Determine key biophysical parameters such as effective guide length for nucleases or optimal activity conditions [24].

Table 2: Quantitative Results from Ortholog Screening of IscB Nucleases

| Ortholog | Amino Acid Length | Optimal Guide Length | Editing Efficiency Range | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OrufIscB | 492 aa | 14-15 nt | 0.2% to 8% | Beta hairpin REC linker |

| OgeuIscB | ~400-500 aa | 16 nt | Lower than OrufIscB | Beta hairpin REC linker |

| CzcbIscB | ~400-500 aa | Not specified | Detected activity | REC-like zinc finger |

Data Analysis and Hit Selection

Identify orthologs with highest baseline activity and desirable properties. Prioritize candidates with features associated with improved function (e.g., REC-like inserts in IscBs that interact with guide-target duplexes) [24]. Evaluate effective guide length, as this majorly contributes to specificity; longer effective guides have fewer potential off-targets across the genome [24].

Structural Analysis Protocol

Objective and Principles

Structural analysis aims to characterize and compare the atomic-level features of promising orthologs to identify structural determinants of function and guide atomistic design. This phase utilizes both experimental structures and computational models to understand binding pockets, interaction interfaces, and conformational dynamics.

Homology Modeling Methodology

For targets without experimental structures, generate high-quality structural models using these steps:

Template Identification and Sequence Preparation

- Retrieve kinase domains or other relevant regions (e.g., TbERK8 residues 6-341; HsERK8 residues 12-345) [25].

- Identify suitable templates from PDB using sequence similarity searches. For ERK8 orthologs, MAPK Fus3 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (PDB ID: 2b9f) and MAPK from Cryptosporidium parvum (PDB ID: 3oz6) were used as templates [25].

- Use tools like RaptorX Contact which integrates sequence conservation and evolutionary coupling information using deep neural networks, particularly advantageous for proteins with few PDB homologs [26].

Model Generation and Refinement

Model Quality Assessment

- Validate model quality using multiple metrics: Verify3D for side-chain positioning, ANOLEA for local environment favorability, ProSA for similarity to known structures, and PROCHECK for stereochemical quality [25] [26].

- Compare models with recently released AlphaFold predictions for additional validation [26].

Structural Characterization Techniques

Binding Pocket Analysis

- Predict binding cavity locations using MetaPocket 2.0 [25].

- Calculate pocket volume and characterize hydrophobicity using UCSF Chimera and Schrödinger-Maestro [25].

- Example: In ERK8 ortholog studies, the TbERK8 ATP binding pocket was found to be smaller and more hydrophobic than that of human ERK8, enabling design of ortholog-specific inhibitors [25].

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

- Use Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to characterize secondary structure composition and validate models.

- Analyze spectra using the BeStSel method, which distinguishes eight secondary structure components and can predict protein folds according to CATH classification [28].

- Determine protein stability from thermal denaturation profiles followed by CD [28].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

- Perform MD simulations to understand protein flexibility and conformational changes.

- Example Application: Simulations of human CDK8 with cyclin C revealed CycC's stabilizing effect and specific interaction hotspots, highlighting the importance of including regulatory subunits in computational studies [27].

Diagram 1: Structural analysis workflow (43 characters)

Atomistic Calculation Protocol

Objective and Principles

Atomistic calculation enables precise optimization of protein stability and function through physics-based modeling and energy calculations. This phase implements positive design by stabilizing the desired native state within the evolutionarily constrained sequence space [9].

Molecular Docking Methodology

System Preparation

- Prepare receptor (kinase) and ligand files using AutoDock Tools [25].

- Add hydrogen atoms, compute charges, and assign atom types.

- Define the search space for docking based on binding pocket analysis.

Docking Execution

- Perform molecular docking using AutoDock Vina or similar tools [25].

- Dock ligands into prepared binding sites with appropriate sampling parameters.

- Example: In ERK8 studies, docking predicted FDA-approved compounds as ortholog-specific inhibitors of HsERK8 or TbERK8, which were subsequently validated experimentally [25].

Binding Analysis

- Analyze docking poses based on binding energy and interaction patterns.

- Identify key residues contributing to ligand binding and specificity.

Free Energy Calculations

Binding Free Energy Estimation

- Use methods like MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA to calculate binding free energies from molecular dynamics trajectories.

- Identify interaction hotspots and quantify contribution of specific residues to binding [27].

Stability Optimization Calculations

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Atomistic Calculations

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Tools/Vina | Prepares receptor/ligand files and performs molecular docking | Docking of FDA-approved drugs to ERK8 orthologs [25] |

| AmberEHT Force Field | Energy minimization of homology models | Energy minimization of TbERK8 and HsERK8 models [25] |

| MOE Software | Molecular modeling and simulation | Homology modeling and energy minimization [25] |

| Evolutionary Covariance Data | Guides sequence selection for stability design | Filtering mutations to eliminate misfolding-prone variants [9] |

Integrated Case Study: Engineering Ortholog-Specific Kinase Inhibitors

This case study illustrates the complete workflow applied to discover ortholog-specific inhibitors for Trypanosoma brucei ERK8 (TbERK8), a potential therapeutic target for Human African Trypanosomiasis [25].

Ortholog Screening and Selection

Researchers identified TbERK8 as essential for parasite proliferation through RNA interference screens, noting that the compound AZ960 selectively inhibited TbERK8 over human ERK8 (HsERK8), while Ro318220 showed opposite selectivity [25].

Structural Analysis and Characterization

Homology models of TbERK8 and HsERK8 kinase domains revealed critical differences: the TbERK8 ATP binding pocket was smaller and more hydrophobic than HsERK8's [25]. Physicochemical characterization using MetaPocket 2.0, UCSF Chimera, and Schrödinger-Maestro quantified these volume and hydrophobicity differences, enabling hypothesis generation about ortholog-specific inhibitor properties [25].

Atomistic Calculations and Experimental Validation

Molecular docking predicted six FDA-approved compounds as potential ortholog-specific inhibitors. Experimental testing identified prednisolone as an HsERK8-specific inhibitor and sildenafil as a TbERK8 inhibitor, confirming the computational predictions [25]. This validated the approach of exploiting structural differences between orthologs to build selective antitrypanosomal agents.

Diagram 2: Integrated inhibitor discovery (36 characters)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Databases | UniRef30/90, UniProt, Metagenomic DBs | Source for homologous sequences and evolutionary information [18] |

| Structural Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold DB | Source of experimental structures and high-quality predictions for templating [29] [26] |

| Modeling Software | RaptorX, MOE, SWISS-MODEL, I-TASSER, AlphaFold | Generate 3D structural models from sequence [25] [26] |

| Validation Tools | ProSA-web, PROCHECK, Verify3D, QMEANDisCo | Assess model quality and stereochemical validity [25] [26] |

| Docking Tools | AutoDock Tools, AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking and binding pose prediction [25] |

| MD Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Molecular dynamics simulations for conformational sampling [27] |

| Analysis Tools | UCSF Chimera, PyMOL, BeStSel | Structure visualization, analysis, and spectral interpretation [25] [28] |

The Obligate Mobile Element Guided Activity (OMEGA) system represents a distinct class of miniature RNA-guided nucleases, with IscB being the evolutionary ancestor of the well-characterized Cas9 [24]. These compact systems are particularly compelling candidates for therapeutic genome editing due to their small size (~300–550 amino acids), which renders them more conducive to delivery via adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) compared to bulkier Cas9 systems [24] [30]. Furthermore, their large structured guiding RNA (ωRNA) offers an interface to scaffold additional interactions [24].

Despite these inherent advantages, wild-type IscB proteins presented significant limitations for robust application in human cells. They generally exhibited low editing efficiency and problematic specificity, owing primarily to their short effective guide lengths of approximately 13-15 base pairs [24]. This short guide length drastically increases the number of potential off-target sites across the human genome. For a given target sequence, a 12-nt guide with perfect fidelity would have on average ~4,100 more potential off-targets compared to an 18-nt guide [24]. The challenge, therefore, was to engineer an IscB variant that simultaneously achieved enhanced on-target editing activity while maintaining or improving specificity—a classic trade-off in protein engineering [24] [30]. This case study details the evolution-guided atomistic design of NovaIscB, an optimized variant that successfully balances these properties, creating a powerful new tool for precise genome manipulation.

Engineering Strategies and Methodologies

The development of NovaIscB employed a multi-faceted strategy that integrated large-scale bioinformatics, evolutionary analysis, and structure-guided rational design. The overall workflow, which systematically moved from discovery to validation, is summarized in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Overall Workflow for Engineering NovaIscB. This diagram outlines the key stages of the engineering process.

Ortholog Screening and Lead Identification

The initial phase focused on identifying a promising IscB ortholog as a engineering starting point.

- Methodology: A set of 384 IscB orthologs, selected based on diversity in protein size, ωRNA scaffold type, and taxonomic distribution, were systematically screened [24] [30]. The screening pipeline involved:

- In Vitro Transcription-Translation (IVTT) TAM Screen: Orthologs were first tested for in vitro function and their Target Adjacent Motif (TAM) preferences were characterized [24].

- Mammalian Cell-based Activity Screen: Orthologs showing activity in vitro were subsequently tested in human cells using a pool of 12 guides (20 nt length) per ortholog to assess genome editing capability [24].

- Result Analysis: From the primary screen, 10 IscBs and 2 type II-D Cas9s demonstrated detectable genome editing activity in human cells. Among these, OrufIscB (492 aa) emerged as the top performer, showing a 5- to 10-fold improvement in editing efficiency over the previously reported OgeuIscB, with detectable indels at 14 out of 20 tested genomic sites (efficiencies ranging from 0.2% to 8%) [24]. However, OrufIscB's effective guide length was determined to be only 14-15 nt, confirming the specificity challenge [24]. This made OrufIscB the ideal lead candidate for further engineering.

Evolution-Guided Rational Protein Design

A key insight driving the engineering was the correlation between the presence of specific insertions and mammalian cell activity.

- Rationale: Analysis of active IscB orthologs revealed that eight belonged to the same clade and shared a common feature: a distinct, conserved beta hairpin REC linker located between the bridge helix (BH) and RuvC-II regions [24] [31]. This REC-like domain was hypothesized to facilitate DNA unwinding within eukaryotic chromatin, analogous to the larger REC lobe in Cas9, and might enable an extended guide-target duplex [24].

- Methodology: REC Domain Engineering. Guided by natural evolution and structural predictions from AlphaFold2, the team engineered the REC lobe of OrufIscB [30] [31]. This involved:

- Domain Swapping: Experimenting with swapping in parts of REC domains from different active IscBs and smaller Cas9s.

- Residue-Level Optimization: Making specific amino acid changes to optimize interactions between the engineered REC domain, the DNA substrate, and the ωRNA guide. This was aimed at stabilizing a longer guide-target heteroduplex.

- Methodology: ωRNA Scaffold Engineering. The ωRNA was simultaneously optimized through rational design to reduce its size and enhance its expression in human cells, which contributed to the overall system's efficiency [31].

This "evolution-guided" approach, leveraging nature's blueprint and atomistic structural models, allowed for strategic, targeted modifications rather than relying on random mutagenesis.

Specificity Enhancement through Extended Guide Length

A major goal was to increase the system's effective guide length to improve specificity.

- Experimental Protocol: Guide Length Titration

- Objective: Determine the minimum number of matched bases in the guide-target duplex required for cleavage activity.

- Procedure: The engineered NovaIscB was tested with a series of guide RNAs of varying lengths, typically ranging from 12 nt to 28 nt [24].

- Analysis: Editing efficiency was measured for each guide length (e.g., via indel frequency) to identify the optimal length and the point at which activity is lost. This defines the effective guide length.

- Outcome: Through REC domain engineering, NovaIscB was successfully modified to accommodate and require longer guide RNAs. This increase in effective guide length directly enhances specificity by increasing the number of base-pairing interactions that must be perfectly matched for efficient cleavage, thereby reducing the number of potential off-target sites in the genome [24] [30].

Performance Characterization of NovaIscB

The engineered NovaIscB was rigorously characterized to quantify its improvements. Key performance metrics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of IscB Variants

| Metric | Wild-type OgeuIscB (Baseline) | OrufIscB (Lead) | NovaIscB (Engineered) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (aa) | ~400-500 | 492 | Compact (comparable) | [24] [30] |

| Max Indel Activity | Baseline (Low) | 5-10x over OgeuIscB | ~40% (≥100x over OgeuIscB) | [24] [31] |

| Optimal Guide Length | 16 nt | 14-15 nt | Extended (specificity improved) | [24] [30] |

| Specificity | Low | Low | Improved relative to existing IscBs | [24] [31] |

| Therapeutic Delivery | AAV-compatible | AAV-compatible | AAV-compatible (single vector) | [30] |

Application in Epigenome Editing: OMEGAoff

The compact size and high efficiency of NovaIscB make it an excellent scaffold for building advanced editors.

- Protocol: Construction of OMEGAoff Transcriptional Repressor

- Fusion Protein Design: The NovaIscB protein is fused to a methyltransferase domain (e.g., DNA methyltransferase) [24] [30]. The nuclease activity of NovaIscB is typically deactivated (creating a "dead" NovaIscB or dNovaIscB) for epigenome editing applications.

- Delivery: The fusion construct, along with the engineered ωRNA expression cassette, is packaged into a single adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector. The small size of the NovaIscB system is critical for this step, as it avoids exceeding the AAV's packaging limit [24] [30].

- In Vivo Validation: The AAV vector is administered to animal models (e.g., mice) via an appropriate route (e.g., systemic or local injection). The OMEGAoff system is programmed to target a specific gene promoter. Repression is assessed by measuring mRNA levels of the target gene and relevant phenotypic outcomes [30].

- Results: When programmed to target the Pcsk9 gene (involved in cholesterol regulation) and delivered to mouse livers via AAV, OMEGAoff mediated persistent DNA methylation, leading to significant transcriptional repression and lasting reductions in blood cholesterol levels [24] [30]. This demonstrated the potential of NovaIscB for durable therapeutic applications.

The logical pathway from delivery to phenotypic outcome for OMEGAoff is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. OMEGAoff Mechanism for Persistent Gene Repression.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for NovaIscB-based Genome Editing

| Reagent / Material | Function and Key Features |

|---|---|

| NovaIscB Expression Plasmid | Expresses the engineered NovaIscB protein in mammalian cells. Its compact size allows for inclusion of additional functional domains. |

| Engineered ωRNA Scaffold | The optimized guide RNA scaffold that ensures high expression and stability in human cells, complexing with NovaIscB for target recognition. |

| AAV Vector System | The delivery vehicle of choice for in vivo applications. The system's small size enables single-vector packaging of the entire editor. |

| Methyltransferase Domain | For epigenome editing (e.g., OMEGAoff). Fused to a nuclease-dead NovaIscB to programmably deposit repressive DNA methylation marks. |

| Deaminase Domain (e.g., APOBEC1) | For base editing. Fused to a nuclease-dead NovaIscB to enable precise chemical conversion of a single DNA base without double-strand breaks. |

The engineering of NovaIscB serves as a seminal case study in evolution-guided atomistic design for protein optimization. By strategically combining large-scale ortholog screening, evolutionary analysis of natural protein diversity, and AI-powered structural predictions, the researchers successfully broke the activity-specificity trade-off that often plagues enzyme engineering. The resulting NovaIscB system, with its compact size, high efficiency, and improved specificity, is not only a valuable standalone tool but also a versatile scaffold for a new generation of programmable editors, as evidenced by the successful demonstration of the OMEGAoff epigenome editor in vivo. This framework provides a powerful blueprint for the optimization of other protein-based technologies for therapeutic and biotechnological applications.

The development of targeted imaging probes for cancer detection represents a significant challenge in molecular diagnostics. Traditional methods for generating protein-based binders, such as display technologies and mutation-based engineering, often yield molecules with limited sequence diversity and suboptimal in vivo performance. This case study details the evolution-guided design of BindHer, a novel mini-protein binder targeting the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), a well-established biomarker overexpressed in aggressive breast cancers. The BindHer mini-protein demonstrates that computational design strategies, particularly those incorporating evolutionary principles, can produce diagnostic agents with superior targeting capability and tissue-specific contrast compared to traditionally engineered scaffolds [32].

The clinical imperative for such a designer is clear: while HER2-positive breast cancer is highly aggressive, existing antibody-based diagnostics like trastuzumab face limitations due to their large molecular weight, poor stability, and suboptimal pharmacokinetics, often leading to high background uptake in non-target tissues like the liver [33]. Mini-protein minibinders offer a compelling alternative, characterized by a compact structure, enhanced stability, and reduced immunogenicity [33]. The creation of BindHer highlights a pivotal shift in biologics discovery, moving away from empirical library screening toward a principled, evolution-guided atomistic design paradigm that simultaneously optimizes multiple drug properties for high-contrast in vivo imaging.

Background and Rationale

HER2 as a Therapeutic and Diagnostic Target

Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor that plays a critical role in cell proliferation and survival. Its overexpression is a well-established driver and poor prognostic marker in approximately 20% of breast cancers, as well as in gastric and other carcinomas [33]. This dense and specific expression on the surface of cancer cells makes HER2 an ideal target for molecular imaging. Accurate detection and stratification of HER2 status is crucial for selecting patients who will benefit from HER2-targeted therapies. The extracellular domain IV of HER2, which is the binding site for the therapeutic antibody trastuzumab, serves as a key epitope for binder design [33].

The Limitations of Traditional Scaffolds

Traditional development of small protein scaffolds has historically relied on display technologies and mutation-based engineering. These methods are often laborious, low-throughput, and limited in the sequence and functional diversity they can explore, thereby constraining the therapeutic and diagnostic potential of the resulting molecules [32]. Monoclonal antibodies and their derivatives, such as single-chain variable fragments (scFvs),, while widely used, can suffer from conformational fragility, leading to improper folding or aggregation [33]. Their relatively large size can also limit tumor penetration and result in slow clearance from the bloodstream, leading to high background signal in diagnostic imaging [32] [33].

The Mini-Protein Advantage