Evolutionary Guardians of the Proteome: A Cross-Species Analysis of Protein Quality Control Pathways

This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of protein quality control (PQC) pathways across species, from yeast to humans.

Evolutionary Guardians of the Proteome: A Cross-Species Analysis of Protein Quality Control Pathways

Abstract

This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of protein quality control (PQC) pathways across species, from yeast to humans. It explores the foundational mechanisms of PQC, including chaperone-mediated refolding, the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), and autophagy. The article delves into methodological approaches for studying PQC, examines how these systems fail in disease states, and presents a comparative analysis of their conservation and specialization. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis highlights PQC as a critical target for therapeutic interventions in neurodegenerative diseases and other proteinopathies, offering insights for future biomedical research.

Core Machinery of Cellular Proteostasis: Unraveling Universal Protein Quality Control Strategies

Cellular protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, is a cornerstone of cellular health and functionality in all living organisms [1]. This delicate balance is maintained by an elaborate network of molecular chaperones, folding enzymes, and degradation machineries that constitute the protein quality control (PQC) system [2]. The continuous challenge of managing misfolded proteins—arising from stochastic fluctuations, genetic mutations, or environmental stresses—has driven the evolution of three primary defense strategies: refolding, degradation, and sequestration [2]. When these systems are overwhelmed, a pathological state of dysproteostasis occurs, which is implicated in a growing list of human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, metabolic syndromes, and cancer [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these three core PQC pathways, examining their mechanisms, key components, and experimental methodologies across biological systems to inform drug discovery and basic research.

Comparative Analysis of PQC Pathways

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three primary protein quality control strategies.

Table 1: Core Protein Quality Control Pathways: A Comparative Overview

| Feature | Refolding | Degradation | Sequestration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Restore native conformation and function [2] | Irreversible elimination of damaged proteins [2] | Spatial isolation of misfolded/aggregated proteins [2] [3] |

| Key Molecular Players | Hsp70, Hsp90, Hsp60/TRiC, J-proteins [1] [2] | 26S Proteasome, Ubiquitin ligases, p97/VCP [3] | p62/SQSTM1, TAX1BP1, Vimentin, HDAC6 [3] |

| Cellular Location | Cytosol, Nucleus, Organelles [1] | Cytosol, Nucleus [3] | Pericentriolar Aggresomes, Quality Control Compartments [2] [3] |

| Energetic Cost | High (ATP-dependent) [2] | Very High (ATP-dependent) [2] | Lower (Mainly structural) |

| Typical Substrates | Newly synthesized, mildly misfolded proteins [2] | Irreversibly damaged, oxidized, or regulator proteins [2] | Aggregation-prone, overloaded, or persistent aggregates [2] [3] |

| Disease Link | Chaperonopathies [1] | Proteasome-associated autoinflammatory syndromes [1] | Neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer's, Parkinson's) [1] [3] |

Experimental Analysis of PQC Pathways

Modern techniques allow researchers to dissect the mechanisms and efficiency of each PQC pathway. The table below outlines key experimental approaches and the quantitative data they generate.

Table 2: Experimental Methodologies for Analyzing PQC Pathways

| Method | Measured Parameters | Application in PQC Pathways | Key Experimental Readouts |

|---|---|---|---|

| cDNA Display Proteolysis [4] | Thermodynamic folding stability (ΔG) | Refolding: Measures stability of variants and maps energy landscapes. | - ΔG (folding free energy)- Protease resistance (K50)- Effects of thousands of mutations in parallel |

| Proximity Proteomics (e.g., TurboID) [3] | Protein-protein interactions and spatial organization | Sequestration & Degradation: Identifies protein content of aggresomes and associated machinery. | - Proximitome of cargo receptors (e.g., TAX1BP1)- Composition of PQC compartments- Recruitment of chaperones, p97, proteasome |

| Aggresome Clearance Assay [3] | Kinetics of aggregate formation and disposal | Sequestration & Degradation: Monitors aggresome formation and autophagic clearance. | - % cells with aggresomes (via microscopy)- Co-localization with LC3, Ubiquitin, TAX1BP1- Clearance half-life after stress relief |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Folding Stability Profiling using cDNA Display Proteolysis This protocol, adapted from a mega-scale study, measures the thermodynamic stability of thousands of protein variants simultaneously [4].

- Library Preparation: Synthesize a DNA library encoding the protein variants of interest.

- Cell-Free cDNA Display: Transcribe and translate the DNA library in vitro using a cDNA display system, generating protein–cDNA complexes.

- Proteolysis Reaction: Incubate the protein–cDNA complexes with a series of increasing concentrations of protease (e.g., trypsin or chymotrypsin).

- Reaction Quenching & Pull-Down: Quench the proteolysis reactions and isolate intact (protease-resistant) protein–cDNA complexes via an affinity tag.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Quantify the surviving sequences for each protease concentration by deep sequencing. Infer the folding stability (ΔG) of each variant using a Bayesian kinetic model that accounts for cleavage rates in the folded and unfolded states [4].

Protocol 2: Analyzing Aggresome Clearance via Selective Autophagy (Aggrephagy) This protocol details the induction and monitoring of aggresome clearance, a key sequestration and degradation pathway [3].

- Aggresome Induction: Treat cells (e.g., HeLa) with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., Bortezomib, 10-20 µM) for 8 hours to trigger the accumulation of ubiquitinated aggregates.

- Synchronized Clearance: Wash out the inhibitor to allow recovery and the initiation of clearance mechanisms.

- Inhibition for Pathway Analysis: To capture intermediates, treat cells during the recovery phase with inhibitors:

- Immunofluorescence & Quantification: Fix cells at various time points and stain for ubiquitin, the autophagy receptor TAX1BP1, the autophagosome marker LC3, and the aggresome structural protein vimentin. Clearance efficiency is quantified as the percentage of cells containing ubiquitin-/vimentin-positive aggresomes over time [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Protein Quality Control Research

| Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib (Proteasome Inhibitor) | Induces proteotoxic stress by blocking the 26S proteasome, leading to accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and aggresome formation [3]. | Triggering the sequestration pathway for aggrephagy studies [3]. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | Inhibitor of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) that prevents autophagosome-lysosome fusion and lysosomal acidification, blocking degradative autophagy [3]. | Trapping and visualizing substrates targeted for autophagic degradation [3]. |

| CB-5083 (p97/VCP Inhibitor) | Potent and selective ATP-competitive inhibitor of the p97/VCP unfoldase, crucial for both proteasomal degradation and aggresome disassembly [3]. | Probing the role of p97 in extracting ubiquitinated proteins from aggregates or membranes prior to degradation [3]. |

| TurboID System | An engineered biotin ligase that labels proximal proteins in vivo with high temporal resolution, enabling interaction profiling [3]. | Mapping the proteome of dynamic PQC compartments like aggresomes and aggrephagosomes [3]. |

| cDNA Display Kit | A cell-free platform that covalently links a protein to its encoding cDNA, enabling high-throughput screening and selection [4]. | Profiling the folding stability of thousands of protein mutants in a single experiment [4]. |

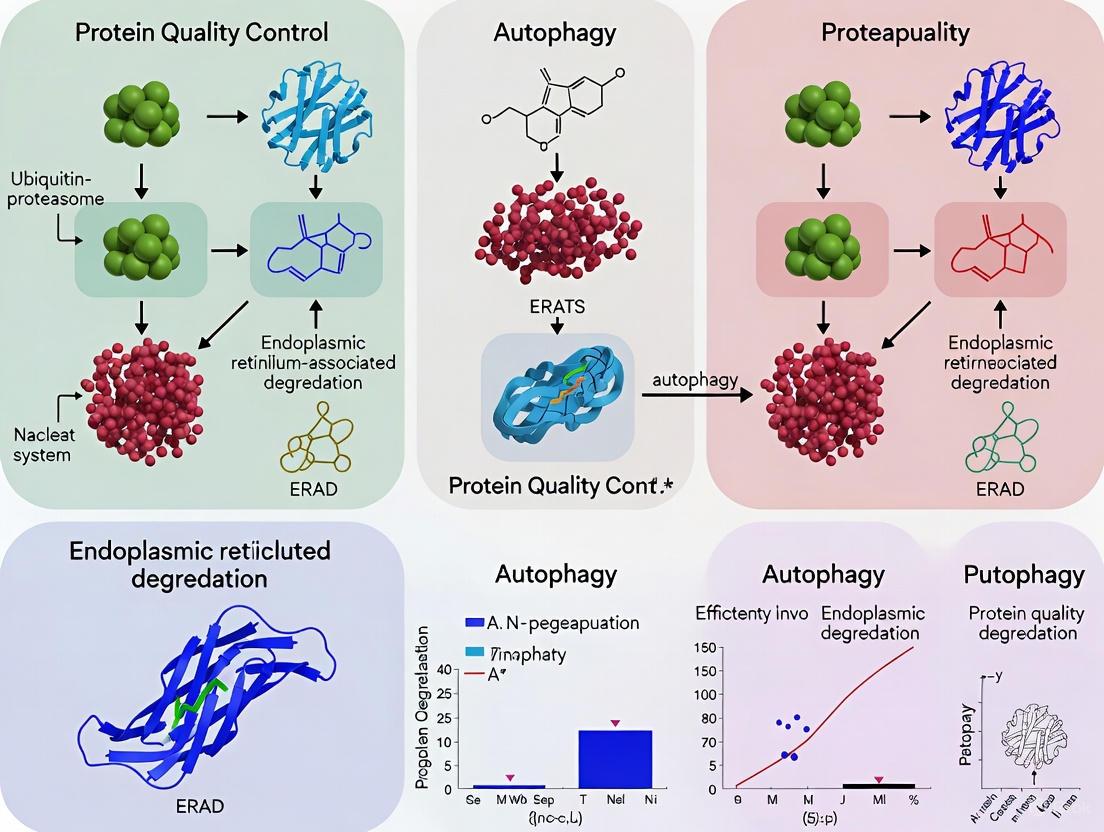

Pathway Diagrams and Logical Relationships

The Proteostasis Network: A Cellular Decision Tree

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and interconnections between the three major protein quality control pathways when the cell encounters a misfolded protein.

High-Throughput Folding Stability Workflow

This diagram outlines the experimental workflow for the cDNA display proteolysis method, a key technique for studying the refolding pathway on a large scale.

The integrated and complementary actions of refolding, degradation, and sequestration form a resilient triad that preserves proteome integrity. As the comparative data show, each pathway has distinct operational parameters, advantages, and failure modes linked to specific diseases. The advent of mega-scale stability profiling [4] and sophisticated spatial proteomics [3] is transforming our ability to dissect these systems quantitatively. This objective comparison underscores that therapeutic interventions targeting the PQC network—such as chaperone modulators, proteasome inhibitors, or activators of aggrephagy—must account for the crosstalk and compensatory mechanisms between these pathways. A systems-level understanding of this triad is paramount for developing effective treatments for the growing list of diseases associated with dysproteostasis.

Molecular chaperones constitute an essential network of proteins that maintain cellular protein homeostasis (proteostasis) by ensuring the proper folding, assembly, and localization of other proteins [2]. These chaperone systems function as first responders in the cellular environment, preventing protein misfolding and aggregation that can lead to toxic species implicated in various conformational diseases [5] [6]. The integrity of the proteome is essential for cell viability, and chaperones play a central role in preserving this integrity by employing parallel strategies that refold, degrade, or sequester misfolded polypeptides [2]. Within this sophisticated network, two major ATP-dependent chaperone systems—Hsp70 and the chaperonin TRiC/CCT—exemplify distinct yet complementary mechanisms for managing proteome health across diverse species.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of the Hsp70 and TRiC/CCT chaperone systems, objectively examining their structures, functional mechanisms, substrate specificities, and roles in protein quality control pathways. We present experimental data and methodologies that highlight how these systems operate independently and cooperatively to address protein folding challenges, with implications for understanding evolutionary conservation and divergence in protein quality control mechanisms from yeast to humans.

Structural Organization and Functional Classification

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Hsp70 and TRiC/CCT Chaperone Systems

| Feature | Hsp70 System | TRiC/CCT Complex |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Architecture | Monomeric protein with two domains [7] | 1 MDa hetero-oligomer with two stacked octameric rings [8] |

| Domain Organization | N-terminal ATPase domain + C-terminal substrate-binding domain [7] | Three domains per subunit: apical, intermediate, and equatorial [8] |

| Subunit Composition | Single polypeptide with Hsp40 co-chaperones [9] | Eight paralogous subunits (CCT1-8) per ring [8] |

| ATP Dependence | ATP-dependent functional cycle [10] | ATP-dependent folding cycle [8] |

| Primary Functions | Stabilize unfolded chains, prevent aggregation, translocation [7] | Folding of complex proteins, assembly of oligomeric complexes [8] |

| Substrate Scope | Broad specificity for hydrophobic residues [7] | ~10% of cytosolic proteome, including obligate substrates [8] |

| Obligate Substrates | None identified | Actin, tubulin, VHL tumor suppressor [8] [11] |

| Cooperation Partners | Hsp40, nucleotide exchange factors [9] | Prefoldin, Hsp70, phosducin-like proteins [8] [12] |

Quantitative Functional Capacities

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics and Substrate Profiles

| Parameter | Hsp70 System | TRiC/CCT Complex |

|---|---|---|

| Folding Chamber Capacity | Binds extended hydrophobic regions [7] | Accommodates proteins up to 223 kDa [8] |

| Key Experimental Readouts | ATPase activation, substrate binding affinity [10] | Lid closure assays, actin/tubulin folding efficiency [13] |

| Representative Substrates | Nascent polypeptide chains, stress-denatured proteins [2] | Actin, tubulin, WD-40 repeat proteins, cell cycle regulators [8] |

| Genetic Essentiality | Essential in eukaryotes [9] | Essential for eukaryotic cell viability [8] |

| Aggregation Suppression | Binds exposed hydrophobic residues [7] | Isolates unfolding proteins in central cavity [7] |

| Disease Associations | Neurodegenerative diseases, cancer [6] | Neuropathies, various malignancies, cardiovascular diseases [8] |

Mechanistic Workflows and Cooperative Folding

Individual Folding Mechanisms

The Hsp70 and TRiC/CCT systems employ fundamentally different mechanical strategies for protein folding assistance. The Hsp70 system functions through a dynamic binding and release cycle that stabilizes transiently exposed hydrophobic regions on substrate proteins [7]. This cycle is regulated by ATP hydrolysis and co-chaperones of the Hsp40 family, which enhance ATPase activity and substrate targeting [9]. When ATP is bound to the N-terminal domain, Hsp70 exhibits low substrate affinity and rapid binding kinetics. ATP hydrolysis triggers a conformational shift to a high-affinity state that stabilizes the bound substrate, while nucleotide exchange facilitates substrate release [10]. This mechanism allows Hsp70 to prevent aggregation of unfolded polypeptides during translation or membrane translocation [7].

In contrast, TRiC/CCT employs an encapsulated folding mechanism wherein substrates are isolated within a central chamber that shields them from the crowded cellular environment [8]. This sophisticated chamber is formed by the coordinated arrangement of eight different subunits that create a heterogeneous interior surface with distinct binding properties across subunits [8]. The TRiC folding cycle is driven by ATP binding and hydrolysis, which induces large conformational changes including lid formation that transiently encapsulates substrates [8]. This encapsulated environment allows proteins, particularly those with complex topologies or slow folding kinetics, to reach their native states without exposure to cytoplasmic factors that might promote aggregation [8].

Figure 1: Comparative Folding Pathways of Hsp70 and TRiC/CCT Chaperone Systems

Integrated Folding Pathway for Complex Substrates

For certain structurally complex proteins, the Hsp70 and TRiC/CCT systems function cooperatively in a sequential folding pathway rather than as independent folding agents. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein (VHL) exemplifies this cooperative mechanism, requiring both chaperone systems for proper assembly with its binding partners elongin B and C [11]. Experimental analysis in yeast conditional mutants demonstrates that functional both TRiC and Hsp70 are essential for VBC complex formation, with defects observed in strains carrying temperature-sensitive mutations in either CCT4 (a TRiC subunit) or SSA1 (cytosolic Hsp70) [11].

The cooperative mechanism follows an ordered pathway where Hsp70 initially engages the nascent VHL polypeptide, subsequently promoting or stabilizing its transfer to TRiC for completion of the folding process [11]. This transfer mechanism is evidenced by the finding that loss of Hsp70 function disrupts both Hsp70 and TRiC binding to VHL, while the TRiC mutation decreases TRiC binding but does not affect Hsp70 interaction [11]. This indicates Hsp70 acts upstream of TRiC in the VHL folding pathway, potentially presenting the substrate in a transfer-competent state.

Figure 2: Cooperative Folding Pathway for VHL Tumor Suppressor Complex

Experimental Analysis and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols

Chaperone-Dependent Folding Reconstitution Assay (VHL-Elongin BC)

The assembly of the VHL-elongin BC tumor suppressor complex provides a well-characterized experimental system for analyzing cooperative chaperone function. The following methodology, adapted from [11], enables specific assessment of Hsp70 and TRiC requirements in folding:

Expression System Setup:

- Utilize Saccharomyces cerevisiae as model organism with conditional chaperone mutants

- Employ cct4ts strain (temperature-sensitive TRiC mutant) and ssa1-45 strain (temperature-sensitive Hsp70 mutant) with isogenic wild-type controls

- Clone His₆-VHL coding region into pESC vector under GAL1 promoter for galactose-inducible expression

- Clone myc-tagged elongin B and C into pESC vector with different selection markers

Folding Assay Procedure:

- Transform yeast strains with VHL and elongin BC plasmids and select on synthetic glucose medium lacking appropriate amino acids

- Grow overnight cultures in selective glucose medium at permissive temperature (23°C for temperature-sensitive strains)

- Induce expression by transferring to synthetic galactose medium (SGal) and grow for 16-20 hours at 30°C

- For temperature-sensitive studies, shift cultures to 37°C for 15 minutes to induce mutant phenotype before VHL induction

- For rapid induction kinetics, use copper-inducible promoter system (0.2 mM CuSO₄ addition for 45 minutes)

Analysis Methods:

- Prepare cell extracts using lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors

- Assess VBC complex formation via co-immunoprecipitation using anti-myc antibodies

- Analyze chaperone interactions by immunoprecipitation followed by Western blotting with Hsp70 and TRiC antibodies

- Confirm proper folding via protease sensitivity assays and native gel electrophoresis

TRiC Structural and Functional Analysis

Advanced structural techniques have provided detailed insights into TRiC assembly and mechanism. The following integrated approach, based on [13], enables comprehensive characterization:

Recombinant TRiC Production:

- Co-express all eight human CCT subunits (CCT1-8) in insect cell system (Trichoplusia ni)

- Incorporate CBP (calmodulin-binding peptide) tag on CCT1 for affinity purification

- Validate assembly via negative stain electron microscopy confirming stacked double-ring structure

- Verify subunit arrangement through crosslinking mass spectrometry

Functional Assessment:

- Confirm ATP-dependent lid closure via conformational assays

- Test folding competence using actin refolding as functional readout

- Analyze ATPase activity under varying nucleotide conditions

Structural Characterization:

- Separate subunits by reverse phase chromatography under denaturing conditions

- Determine subunit masses and post-translational modifications via intact protein mass spectrometry

- Identify co-purifying proteins and substrates through bottom-up proteomics

- Investigate complex stability using native mass spectrometry under varying conditions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Chaperone Mechanism Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Conditional Yeast Mutants | Genetic dissection of chaperone requirements | cct4ts (TRiC mutant), ssa1-45 (Hsp70 mutant) [11] |

| Epitope-Tagged Constructs | Detection, purification, and interaction studies | His₆-VHL, myc-elongin B/C for IP experiments [11] |

| Recombinant TRiC Complex | Structural and biochemical studies | Insect cell-derived human TRiC [13] |

| ATP Analogues | Probing ATP-dependent conformational changes | Non-hydrolyzable analogues for trapping specific states |

| Crosslinking Reagents | Stabilizing transient interactions for structural biology | Crosslinking mass spectrometry of subunit arrangements [13] |

| Chaperone-Specific Antibodies | Detection, quantification, and immunoprecipitation | Western blot analysis of chaperone-substrate interactions [11] |

| Native Mass Spectrometry | Analyzing intact complexes and subunit stoichiometry | Mass measurement of TRiC complex and subunits [13] |

Evolutionary and Functional Perspectives

The comparative analysis of Hsp70 and TRiC/CCT reveals both specialized functions and cooperative integration within protein quality control pathways across eukaryotic species. The Hsp70 system represents a more ancient and conserved folding mechanism present in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes, though with increasing complexity in co-chaperone networks and specialized isoforms in higher organisms [5] [9]. In contrast, TRiC/CCT is a eukaryotic innovation that emerged to handle the folding requirements of structurally complex proteins that constitute the expanded eukaryotic proteome [8]. This evolutionary trajectory is reflected in TRiC's essential role in folding eukaryotic-specific proteins like actin and tubulin, as well as the intricate regulatory components that characterize eukaryotic signaling networks [8].

The cooperative functioning between these systems, as exemplified by VHL folding, demonstrates how eukaryotic cells integrate chaperone networks to manage challenging folding tasks. This cooperation likely enhances the folding efficiency of complex proteomes and provides quality control checkpoints for proteins with particular biological importance, such as tumor suppressors [11]. The conservation of these cooperative mechanisms from yeast to humans highlights their fundamental importance in eukaryotic proteostasis and suggests ancient evolutionary origins for chaperone network integration.

Implications for Disease and Therapeutic Development

Understanding the distinct yet complementary functions of Hsp70 and TRiC/CCT has significant implications for comprehending disease mechanisms and developing therapeutic interventions. Both systems are implicated in conformational diseases—Hsp70 in neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's disease [6], and TRiC/CCT in various neuropathies, cardiovascular diseases, and malignancies [8]. The emerging understanding of their cooperative functions suggests that therapeutic strategies targeting chaperone networks may need to consider system-level interactions rather than individual components.

The experimental methodologies outlined here provide frameworks for investigating how disease-associated mutations impact chaperone-dependent folding pathways and for screening potential therapeutic compounds that modulate chaperone function. Particularly promising are approaches that enhance the protective functions of these chaperone systems to prevent aggregation of disease-associated proteins, with potential applications across multiple conformational disorders [2] [6]. As our understanding of these first responder systems deepens, so too does the potential for developing targeted interventions that restore proteostasis in human disease.

Cellular protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, represents a fundamental biological process that ensures the proper folding, modification, trafficking, and degradation of proteins to maintain a functional proteome [14]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) serves as a crucial regulatory hub within this network, responsible for the selective degradation of damaged, misfolded, and regulatory proteins [15]. This system plays an indispensable role in diverse cellular processes including cell cycle regulation, gene expression, stress responses, and immune activation [16] [15]. Dysregulation of the UPS is implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous human diseases, particularly neurodegenerative disorders, cancer, and cardiovascular conditions [15] [17]. The selective targeting of misfolded proteins for degradation represents one of the UPS's most critical functions, preventing the toxic accumulation of abnormal proteins that characterizes many age-related diseases [18] [17]. This review examines the molecular mechanisms underlying UPS-mediated recognition and degradation of misfolded proteins, comparing key protein quality control pathways across species and evaluating emerging therapeutic technologies that exploit these mechanisms.

Molecular Mechanisms of UPS-Mediated Protein Degradation

The Ubiquitination Cascade

The UPS operates through a sophisticated enzymatic cascade that labels target proteins with ubiquitin for proteasomal destruction. This process involves sequential action of three enzyme classes: ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3) [15]. The E3 ubiquitin ligases provide substrate specificity, recognizing particular misfolded proteins or degradation signals and facilitating ubiquitin transfer from E2 enzymes to lysine residues on the target protein [19]. Ubiquitination can manifest in different forms—monoubiquitination, multi-monoubiquitination, or polyubiquitination—with distinct biological consequences [15]. Specifically, polyubiquitin chains linked through lysine 48 (K48) or lysine 11 (K11) typically signal proteasomal degradation, whereas K63-linked chains often regulate cellular signaling and damaged organelle clearance [15].

Recent structural biology breakthroughs have illuminated how the proteasome recognizes specific ubiquitin signals. Cryo-EM studies of human 26S proteasome complexes have revealed that K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chains are recognized through a multivalent mechanism involving a previously unknown K11-linked ubiquitin binding site formed by RPN2 and RPN10, in addition to the canonical K48-linkage binding site [20]. This specialized recognition system enables fast-tracked degradation of proteins during cell cycle progression and proteotoxic stress, demonstrating the sophistication of ubiquitin code interpretation [20].

Proteasomal Recognition and Degradation

The 26S proteasome constitutes a massive multi-catalytic complex comprising a 20S core particle capped by 19S regulatory particles [15]. The regulatory particles recognize ubiquitinated substrates, unfold them, and translocate them into the core particle for proteolysis [15]. Three constitutive ubiquitin receptors—RPN1, RPN10, and RPN13—located within the 19S regulatory particle facilitate substrate recognition [20]. Additionally, specialized proteasome isoforms such as the immunoproteasome enhance the generation of antigenic peptides for immune presentation during inflammatory challenges [15].

Table 1: Key Components of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Component | Structure | Function | Specialized Forms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin | 76-amino-acid polypeptide | Tags proteins for degradation | Various chain linkages (K48, K11, K63) dictate fate |

| E3 Ligases | 600+ human varieties | Substrate recognition; transfer ubiquitin to target | CRL4CRBN [19]; CHIP [18] |

| 26S Proteasome | 20S core + 19S regulatory particles | Protein degradation | Immunoproteasome (immune cells) [15] |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | Multiple families | Remove ubiquitin; regulate degradation | UCHL5 (preferentially processes K11/K48 chains) [20] |

Comparative Analysis of Protein Quality Control Across Species

Protein quality control systems exhibit both remarkable conservation and strategic diversification across evolutionary lineages. The bacterial protein quality control network, comprising chaperones, proteases, and protein translational machinery, influences molecular evolution by modulating epistasis, evolvability, and the navigability of protein space [21]. In eukaryotes, the endoplasmic reticulum quality control (ERQC) system ensures accuracy during glycoprotein folding, with species-specific variations reflecting distinct physiological demands [22].

The fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans possesses an evolutionarily unique N-glycan-dependent ERQC system that differs significantly from mammalian systems. Unlike most eukaryotes, C. neoformans lacks homologous genes to ALG6, ALG8, and ALG10, which encode glucosyltransferases that add glucose residues to core N-glycans [22]. Consequently, its Dol-PP-linked glycans primarily comprise Man7GlcNAc2 and Man8GlcNAc2 without glucose residues, making them more susceptible to trimming by ER α-1,2 mannosidases [22]. This system plays pivotal roles in cellular fitness and extracellular vesicle transport, highlighting how UPS adaptations reflect specific environmental challenges and life history strategies.

Table 2: Comparative Protein Quality Control Systems Across Species

| Organism/System | Key Components | Unique Features | Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mammalian Cells | E1, E2, E3 enzymes; 26S proteasome; DUBs | K11/K48-branched ubiquitin recognition; immunoproteasome | Misfolded protein clearance; immune regulation [15] [20] |

| Bacteria | DnaK, GroEL, proteases | Molecular chaperones as source of mutational robustness | Protein folding; influence on evolutionary trajectories [21] |

| C. neoformans (Fungus) | Ugg1, Mns1, Mns101, Mnl1, Mnl2 | Unique N-glycan pathway lacking ALG6, ALG8, ALG10 | Cellular fitness; extracellular vesicle transport; virulence [22] |

| Plant Cells | Not covered in search results | Not covered in search results | Not covered in search results |

Emerging Technologies for Targeted Protein Degradation

PROTACs and Molecular Glues

Targeted protein degradation (TPD) technologies represent a revolutionary therapeutic strategy that hijacks endogenous UPS mechanisms to eliminate disease-causing proteins [19] [23]. Two principal approaches have emerged: proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) and molecular glues. PROTACs are heterobifunctional molecules comprising two ligands joined by a linker—one binding the target protein and the recruiting an E3 ubiquitin ligase [19] [18]. Molecular glues, by contrast, are small monovalent compounds that induce novel interactions between E3 ligases and target proteins that wouldn't normally bind [19].

The E3 ligase CRBN (Cereblon) has emerged as a platform of choice for TPD due to its well-characterized structure, favorable pharmacokinetic profile, and existing clinical precedent [19]. CRBN enables both molecular glues and PROTACs to target proteins previously considered "undruggable," significantly expanding the therapeutic landscape [19]. As of 2025, the TPD field approaches a historic milestone with the New Drug Application submission for vepdegestrant, a PROTAC developed for ER+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer with ESR1 mutations, which may become the first FDA-approved PROTAC therapy [19].

BioPROTACs for Neurodegenerative Diseases

Biological PROTACs (BioPROTACs) represent an innovative approach that utilizes natural protein binding partners or antibodies rather than small molecules to target proteins for degradation [18]. A groundbreaking study published in Nature Communications in 2025 demonstrated the development of a BioPROTAC specifically targeting misfolded SOD1 variants associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [18].

This BioPROTAC, termed MisfoldUbL, incorporates single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) derived from monoclonal antibodies that specifically recognize the electrostatic loop of SOD1—a region inaccessible in the properly folded protein [18]. These scFvs were fused to a truncated catalytic domain of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIPΔTPR) via a GSGSG linker [18]. The resulting construct selectively degraded multiple disease variants of SOD1 while sparing natively folded wild-type SOD1, addressing a critical therapeutic challenge in ALS treatment [18].

Diagram 1: BioPROTAC Mechanism for Selective Degradation of Misfolded SOD1. The scFv domain binds specifically to misfolded SOD1 with exposed electrostatic loops, while native SOD1 with protected epitopes remains unaffected. The E3 ligase domain facilitates ubiquitination, leading to proteasomal degradation.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Preclinical Models for TPD Evaluation

Humanized CRBN Mouse Models

Species differences in UPS components present significant challenges for preclinical evaluation of TPD therapies. Standard rodent models often fail to predict human responses because mouse CRBN differs from human CRBN [19]. To address this limitation, Biocytogen developed humanized CRBN mice in which the mouse Crbn gene is entirely replaced by human CRBN, enabling more accurate assessment of CRBN-targeting degraders [19].

Functional validation experiments demonstrated that lenalidomide, a CRBN-binding molecular glue, triggers IL-2 secretion in naïve CD4+ T cells from B-hCRBN mice but not in wild-type controls, confirming functional engagement of human CRBN in immune signaling [19]. Importantly, toxicity studies revealed that CC-885, a next-generation molecular glue that degrades GSPT1, causes rapid, species-specific lethality (~35 hours) in B-hCRBN mice, while wild-type mice show no toxicity [19]. This highlights the critical importance of humanized models for predicting on-target human-specific toxicities that standard models miss.

BioPROTAC Transgenic Models

For evaluating BioPROTAC efficacy in neurodegenerative disease, researchers developed a transgenic mouse line expressing the MisfoldUbL BioPROTAC in the SOD1G93A background, a well-established ALS model [18]. This compound transgenic approach demonstrated that BioPROTAC expression delays disease progression, reduces insoluble SOD1 accumulation in the brain, protects spinal cord motor neurons, and preserves innervated neuromuscular junctions [18].

Table 3: Experimental Data from Targeted Protein Degradation Studies

| Experimental Model | Intervention | Key Metrics | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-hCRBN Mice [19] | Lenalidomide (10-100 µM) | IL-2 secretion in CD4+ T cells | Significant increase in B-hCRBN mice only |

| B-hCRBN Mice [19] | CC-885 (5 mg/kg) | Survival rate; body weight; histopathology | 100% lethality at ~35 hours in B-hCRBN; no toxicity in wild-type |

| HEK293 Cells [18] | BP2 BioPROTAC | SOD1A4V-EGFP levels | 17-38% reduction in misfolded SOD1 |

| SOD1G93A Mouse Model [18] | MisfoldUbL BioPROTAC | Disease progression; motor neuron survival | Delayed disease progression; protected motor neurons |

| In Vitro Ubiquitination [20] | K11/K48-branched chains | Proteasome binding affinity | Enhanced recognition vs. homotypic chains |

Methodological Approaches

BioPROTAC Screening and Validation

The development of effective BioPROTAC degraders requires systematic screening approaches. The misfolded SOD1 BioPROTAC study employed a comprehensive panel of seven single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) derived from monoclonal antibodies that specifically recognize aggregated SOD1 in ALS patient tissue [18]. These scFvs were fused with a panel of eight proteins possessing ubiquitination functionality of E3 ligases [18]. Screening across three cell lines (HEK293, Neuro-2A, and SH-SY5Y) identified lead candidates based on reduction of SOD1A4V-EGFP levels and decreased formation of insoluble aggregates [18].

The most effective BioPROTAC (BP2) reduced the proportion of cells with insoluble aggregates across multiple SOD1 mutants (A4V, G93A, G85R, D90A, V148G, H46R, G37R, C6G, and E100G) by 55-76% compared to controls [18]. This broad specificity for misfolded SOD1 variants while sparing wild-type SOD1 demonstrates the potential for selective degradation of pathological protein species.

Diagram 2: BioPROTAC Development Workflow. The process involves generating antibody fragments against misfolded proteins, fusing them with E3 ligase domains, and conducting sequential in vitro and in vivo validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for UPS and TPD Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humanized Mouse Models | B-hCRBN mice [19] | Preclinical evaluation of CRBN-based degraders | Critical for human-specific efficacy/toxicity |

| E3 Ligase Modulators | Lenalidomide, CC-885 [19] | Molecular glue probes; positive controls | Dose-dependent effects; species-specific responses |

| Ubiquitin Chain Tools | K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chains [20] | Structural studies; proteasome binding assays | Enhanced proteasome recognition vs. homotypic chains |

| Cell-Based Screening Systems | HEK293, Neuro-2A, SH-SY5Y [18] | BioPROTAC efficacy screening | Multiple cell lines recommended for validation |

| Disease Model Systems | SOD1G93A transgenic mice [18] | Neurodegenerative disease TPD evaluation | BioPROTAC expression delays disease progression |

| Analytical Methods | Ub-AQUA, Lbpro* Ub clipping [20] | Ubiquitin chain linkage quantification | Mass spectrometry-based precision |

The ubiquitin-proteasome system represents a master regulator of proteostasis through its selective targeting of misfolded proteins. Comparative studies across species reveal both conserved mechanisms and specialized adaptations reflecting distinct evolutionary pressures. Emerging technologies—particularly PROTACs, molecular glues, and BioPROTACs—demonstrate remarkable potential for treating conditions characterized by toxic protein accumulation, such as neurodegenerative diseases [18] [17]. The clinical advancement of vepdegestrant and the sophisticated BioPROTAC strategy for misfolded SOD1 degradation highlight the accelerating translation of UPS-targeted therapies [19] [18]. Future research directions include developing tissue-specific degraders, overcoming delivery challenges through nanotechnologies [23], and expanding the repertoire of E3 ligases amenable to therapeutic exploitation. As our understanding of ubiquitin signaling and proteasome biology deepens, so too will our ability to manipulate this system to combat human disease.

The autophagy-lysosomal pathway (ALP) serves as a critical proteolytic system for maintaining cellular homeostasis by degrading intracellular macromolecules, damaged organelles, and, most notably, bulk protein aggregates that are characteristic of many neurodegenerative diseases [24]. As a primary clearance mechanism for post-mitotic neurons, the ALP provides essential capacity for eliminating aggregation-prone proteins and oligomers that are resistant to other degradation systems [25] [26]. This pathway stands alongside the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) as a cornerstone of cellular protein quality control, with its unique ability to encapsulate and degrade large cytoplasmic contents makes it indispensable for neuronal health and survival [24] [26]. Emerging research continues to reveal the ALP's complex regulatory networks and its potential as a therapeutic target for neurodegenerative disorders where protein aggregation is a hallmark feature [27] [28].

Comparative Analysis of Protein Degradation Pathways

Eukaryotic cells employ three principal proteolytic systems to manage misfolded and aggregated proteins, each with distinct mechanisms, substrate preferences, and functional capabilities as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Protein Degradation Pathways

| Feature | Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) | Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy (CMA) | Macroautophagy (ALP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degradation Mechanism | ATP-dependent unfolding and proteolysis via 26S proteasome | Direct translocation across lysosomal membrane via LAMP2A receptors | Bulk encapsulation via double-membrane autophagosomes |

| Primary Substrates | Short-lived soluble proteins, mildly misfolded proteins | Proteins with KFERQ-like targeting motifs | Protein aggregates, damaged organelles, pathogens |

| Substrate Selectivity | High (ubiquitin tagging) | High (KFERQ sequence recognition) | Low (bulk degradation) with selective options |

| Aggregate Handling Capacity | Limited (proteasome chamber ~13Å diameter) | None (requires unfolded substrates) | High (handles large protein aggregates) |

| Key Molecular Components | E1-E3 ubiquitin ligases, 19S/20S proteasome particles | Hsc70 chaperone, LAMP2A receptor | LC3/ATG8, phagophore, lysosomal hydrolases |

| Neuronal Vulnerability | Highly vulnerable to aggregate inhibition | Diminishes with aging | Essential for long-lived neuronal health |

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents the first line of defense against damaged proteins, employing an enzymatic cascade that tags substrates with ubiquitin chains for recognition and degradation by the proteasome [26]. However, its narrow proteolytic chamber (approximately 13Å in diameter) restricts its capacity to process larger protein aggregates, making it particularly vulnerable to inhibition by oligomeric species characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases [26]. Aggregated β-sheet-rich proteins can physically block the proteasome's gated entry, creating a destructive cycle of further accumulation [26].

Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) provides selective degradation of specific soluble proteins containing a KFERQ pentapeptide motif [24] [26]. This pathway relies on Hsc70 chaperone recognition and LAMP2A receptor-mediated translocation into the lysosome, but requires substrate unfolding and is therefore incapable of processing pre-formed aggregates [26]. CMA activity significantly declines with aging, contributing to the progressive nature of proteinopathies [26].

The autophagy-lysosome pathway (ALP), particularly macroautophagy, specializes in bulk clearance of cellular components that are inaccessible to other systems [24] [26]. Through the formation of double-membrane autophagosomes that engulf cytoplasmic contents and deliver them to lysosomes for degradation, the ALP provides the only known mechanism for eliminating large protein aggregates and damaged organelles [24]. This unique capacity makes it particularly critical for neuronal survival, as post-mitotic cells cannot dilute accumulated toxins through cell division [26].

Figure 1: Comparative Framework of Protein Degradation Systems. The ALP provides the primary route for bulk clearance of protein aggregates, while UPS and CMA handle more specific substrate categories.

Molecular Architecture of the Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway

The ALP operates through a highly orchestrated sequence of molecular events that can be divided into distinct phases: initiation, nucleation, elongation, fusion, and degradation. Understanding this architectural complexity is essential for appreciating its function in aggregate clearance.

Autophagosome Biogenesis and Cargo Recognition

The process initiates with formation of an isolation membrane (phagophore), governed by the ULK1 complex and regulated by nutrient-sensing pathways including mTOR [24]. The Beclin1-Atg14L-Vps34 lipid kinase complex then catalyzes production of PI3P at the phagophore, recruiting downstream effectors including WIPI proteins [24]. The phagophore expands and envelops cytoplasmic cargo, a process requiring two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems that mediate covalent attachment of phosphatidylethanolamine to LC3 (microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3) [28] [24].

LC3 conversion represents a critical commitment point in autophagosome formation. The cytosolic LC3-I form undergoes lipid modification to become membrane-bound LC3-II, which embeds into the expanding autophagosome membrane and serves as a docking site for selective autophagy receptors [28]. While initially considered a non-selective process, macroautophagy demonstrates considerable specificity through adaptor proteins including p62/SQSTM1, NBR1, NDP52, and optineurin, which contain both ubiquitin-binding domains and LC3-interacting regions (LIR) that bridge polyubiquitinated protein aggregates to the growing autophagosome [24].

Lysosomal Fusion and Degradation

Following maturation, autophagosomes traffic through the cytoplasm and fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes, a process mediated by RAB GTPases, SNARE proteins, and lysosomal membrane components including LAMP1 [24]. The resulting single-membrane compartment exposes engulfed cargo to the acidic environment (pH ~4.5) and approximately 60 soluble hydrolases contained within the lysosomal lumen, culminating in degradation of aggregates into reusable biomolecules [24].

Figure 2: ALP Cascade for Protein Aggregate Clearance. The pathway progresses through distinct stages from cargo recognition to lysosomal degradation, with key regulatory steps at LC3 conversion and autophagosome-lysosome fusion.

Experimental Models and Methodologies for ALP Assessment

Investigating ALP function in aggregate clearance requires specialized methodologies spanning molecular, cellular, and organismal approaches. Table 2 summarizes key experimental protocols and their applications in ALP research.

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Studying ALP in Aggregate Clearance

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Key Readouts | Experimental Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Manipulation | ATG gene knockouts (Atg5, Atg7) | Aggregate accumulation, neurodegeneration | Establishing ALP necessity in vivo |

| TFEB/TFE3 overexpression | Lysosomal biogenesis, clearance enhancement | Testing ALP augmentation strategies | |

| Biochemical Assays | LC3-I/II immunoblotting | Autophagosome formation, flux measurement | Quantifying autophagy induction and progression |

| p62/SQSTM1 degradation | Autophagic flux efficiency | Monitoring substrate clearance | |

| Lysosomal enzyme activity | Cathepsin function, pH optimization | Assessing lysosomal degradation capacity | |

| Imaging Approaches | Immunofluorescence co-localization | Aggregate-LC3/LAMP1 association | Visualizing autophagic engulfment |

| TEM autophagic vacuole quantification | Ultrastructural morphology | Confirming autophagy defects | |

| Tandem fluorescence LC3 reporters | Autophagosome-lysosome fusion | Evaluating complete ALP flux | |

| Disease Modeling | α-Synuclein pre-formed fibrils | Spreading pathology, clearance capacity | Testing ALP function in proteostasis |

| Organoid & primary neuronal cultures | Cell-type specific ALP regulation | Human-specific mechanism identification |

Critical Protocol: Monitoring Autophagic Flux

Experimental Objective: Quantify complete ALP progression from induction to degradation, distinguishing increased autophagosome formation from impaired clearance.

Methodological Details:

- LC3 Immunoblotting: Measure conversion from cytosolic LC3-I to lipidated LC3-II, with parallel lysosomal inhibition (bafilomycin A1) to differentiate synthesis from turnover [28].

- p62/SQSTM1 Degradation Assay: Monitor clearance of this selective autophagy receptor, which decreases with functional flux and accumulates during impairment [28].

- Tandem Fluorescent LC3 Reporter: Express LC3 fused to pH-sensitive tag (mRFP-GFP-LC3) where GFP fluorescence quenches in acidic lysosomes while mRFP persists, allowing quantification of autophagosomes (GFP+/mRFP+) versus autolysosomes (GFP-/mRFP+) via confocal microscopy [28].

Interpretation Criteria: Concurrent LC3-II elevation and p62 reduction indicates unimpeded flux; both markers elevated suggests fusion or degradation blockade; reduced LC3-II with p62 accumulation implies induction impairment.

Genetic Models of ALP Dysfunction

Essential In Vivo Evidence comes from nervous system-specific knockout models of essential autophagy genes (Atg5, Atg7), which demonstrate that ALP disruption alone suffices to cause progressive protein aggregation, neurodegeneration, and behavioral deficits [25] [24]. These models establish the non-redundant role of ALP in neuronal proteostasis and provide platforms for testing therapeutic interventions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for ALP Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALP Modulators | Bafilomycin A1, Chloroquine | Lysosomal inhibition | Blockade of autophagic degradation |

| Rapamycin, Torin1 | mTOR inhibition, ALP induction | Activation of autophagy initiation | |

| Pathway Reporters | GFP-LC3 constructs | Autophagosome visualization | Live imaging of ALP dynamics |

| mRFP-GFP-LC3 tandem | Flux progression monitoring | Discrimination of autophagosomes vs. autolysosomes | |

| Selective Agonists | Tat-Beclin 1 peptide | Early autophagy enhancement | BECN1-dependent autophagy activation |

| TFEB activators | Lysosomal biogenesis induction | Transcriptional ALP amplification | |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-LC3 (I/II) | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence | Autophagosome quantification |

| Anti-p62/SQSTM1 | Flux efficiency assessment | Substrate clearance monitoring | |

| Anti-LAMP1/LAMP2 | Lysosomal compartment identification | Organelle integrity and localization |

ALP Dysregulation in Neurodegenerative Proteinopathies

Compromised ALP function emerges as a central feature across neurodegenerative disorders characterized by protein aggregation, creating destructive cycles of impaired clearance and toxic accumulation.

Alzheimer's Disease (AD)

In AD brains, defective autophagosome-lysosome fusion and altered lysosomal pH disrupt clearance of amyloid-β and hyperphosphorylated tau, leading to their accumulation as plaques and neurofibrillary tangles [25] [26]. The unique structural challenges of neurons further complicate ALP function, as autophagosomes forming in distant axons and dendrites must undergo retrograde transport to soma-localized lysosomes, creating opportunities for impaired maturation and fusion [25].

Parkinson's Disease (PD) and α-Synucleinopathies

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) and PD exemplify the bidirectional relationship between ALP dysfunction and protein aggregation. While α-synuclein is normally degraded by autophagy, aberrant conformations can impair lysosomal function, and mutations in lysosomal enzymes like GBA1 (encoding β-glucocerebrosidase) significantly increase PD risk [29]. In Huntington's disease models, mutant huntingtin protein can associate with autophagosome membranes, interfering with cargo recognition and engulfment despite otherwise intact ALP components [25].

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies Targeting ALP

Novel therapeutic approaches are leveraging insights into ALP biology to develop targeted degradation technologies and enhancement strategies for protein aggregation disorders.

Autophagy-Targeting Chimeras (AUTAC, ATTEC, AUTOTAC)

These innovative approaches adapt the proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) concept to the ALP, creating bifunctional molecules that simultaneously bind protein aggregates and LC3 or other autophagy components, directing pathogenic substrates to autophagic degradation [28]. Unlike ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal targeting, these systems utilize the ALP's capacity for bulk degradation without size restrictions, offering particular promise for large, insoluble aggregates resistant to other clearance mechanisms [28].

Transcriptional and Small Molecule Enhancers

TFEB-mediated lysosomal biogenesis represents a powerful approach for comprehensive ALP enhancement, with TFEB activation driving coordinated expression of autophagy and lysosomal genes through CLEAR element binding [24]. Small molecule compounds that enhance ALP function through various mechanisms—including mTOR inhibition, beclin-1 activation, and lysosomal pH optimization—have demonstrated efficacy in preclinical models of neurodegenerative proteinopathies [26].

Cross-Species Conservation and Research Implications

The evolutionary conservation of ALP components from yeast to mammals underscores its fundamental role in cellular homeostasis while highlighting important considerations for translational research. Core autophagy machinery (ATG genes, LC3 homologs, lysosomal hydrolases) maintains remarkable functional conservation, enabling valuable insights from model organisms [27] [24]. However, neuronal-specific adaptations—including unique challenges of polarized cellular architecture and the heightened vulnerability of post-mitotic cells—necessitate careful validation in appropriate neuronal and animal models [26]. The emerging role of the gut-brain axis in ALP regulation further expands the systems biology perspective, with recent evidence demonstrating that gut microbiota-derived metabolites can modulate ALP activity through pathways like AMPK/mTOR and AhR-TFEB signaling [30].

The autophagy-lysosome pathway represents the dominant cellular mechanism for bulk clearance of protein aggregates, with unique capabilities that complement other proteostatic systems. Its capacity to encapsulate and degrade large oligomeric species and inclusion bodies makes it particularly critical for neuronal health, while its dysregulation features prominently across neurodegenerative proteinopathies. Ongoing advances in understanding ALP regulation, coupled with emerging technologies for targeted degradation and pathway enhancement, position this ancient proteolytic system as a promising therapeutic frontier for addressing the fundamental pathology of protein aggregation diseases. Future research elucidating the nuanced interplay between ALP components, their cross-species conservation, and their integration with broader physiological networks will continue to refine our approach to maintaining proteostasis in health and disease.

Maintaining a healthy proteome is essential for cell survival across all species. Protein misfolding, a constant cellular challenge, is linked to a rapidly expanding list of human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, aging, and cancer [2] [31]. Eukaryotic cells employ an elaborate network of molecular chaperones and protein degradation factors to monitor and maintain proteome integrity [2]. Within this network, spatial protein quality control—the sequestration of misfolded proteins into defined cellular compartments—has emerged as a critical mechanism for managing proteotoxic stress and ensuring cellular fitness [31].

This comparative guide examines the fundamental mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and evolutionary conservation of spatial quality control pathways. We focus specifically on compartmentalization and aggregate sequestration strategies across model systems, providing researchers with a structured analysis of how different organisms manage misfolded proteins. Understanding these comparative mechanisms provides crucial insights for drug development targeting protein aggregation diseases, as the cellular capacity to manage the proteome declines during aging, likely underlying the late onset of neurodegenerative diseases caused by protein misfolding [2].

Core Mechanisms of Spatial Sequestration

Cellular protein quality control relies on three interconnected strategies: refolding, degradation, and spatial sequestration of misfolded proteins [2]. The decision between these fates is largely determined by molecular chaperones that recognize misfolded proteins through exposed hydrophobic patches [32]. When refolding is impossible, chaperones can promote degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome system or facilitate compartmentalization.

Table 1: Protein Quality Control Compartments Across Cellular Localities

| Cellular Compartment | Sequestration Site/Process | Key Mediators | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoplasm/Nucleus | Quality Control Compartments (IPOD, JUNQ) | Chaperones (Hsp70, Hsp40), Ubiquitin Ligases (San1, Ubr1) | Concentrate soluble misfolded proteins to enhance refolding or degradation; sequester insoluble aggregates to prevent toxic interactions [2] [31] |

| Mitochondrial Outer Membrane (MOM) | Mitochondria-Associated Degradation (MAD) | E3 Ubiquitin Ligases (Ubr1, San1), Hsp70 (SSA family), Hsp40 (Sis1), Cdc48-Npl4-Ufd1 complex [33] | Recognizes and degrades misfolded peripheral MOM proteins via the ubiquitin-proteasome system [33] |

| Proteasome Assembly Intermediates | Nuclear Sequestration | Proteasomal NLS (Rpt2), Base-Binding Chaperones (Nas6, Rpn14, Hsm3) | Sequesters defective proteasome assembly intermediates away from cytoplasmic assembly sites, preventing formation of defective proteasomes [34] |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum | ER-Associated Degradation (ERAD) | Not specified in results | Not covered in available data |

The spatial compartmentalization of quality control may help cells cope with overloads of aberrant proteins, prevent formation of toxic aggregates, and regulate the inheritance of damaged and/or aggregation-prone species [2]. Insoluble species that may disrupt protein homeostasis are specifically sequestered to prevent their toxic interactions with the quality control machinery [2].

Comparative Analysis of Spatial QC Pathways

Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Sequestration Pathways

In the cytoplasm and nucleus of eukaryotic cells, misfolded proteins are partitioned into distinct quality control compartments. Soluble misfolded proteins are concentrated in specific locations to enhance their refolding or degradation, while insoluble species are sequestered to prevent toxic interactions [2]. Studies in yeast have revealed specialized compartments including the IPOD (Insoluble Protein Deposit) and JUNQ (JUxta Nuclear Quality control compartment) that handle different types of misfolded proteins [31].

The mechanisms governing partition between these compartments involve molecular chaperones and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Molecular chaperones play a critical role in determining the fate of misfolded proteins, actively promoting refolding or, when impossible, facilitating degradation or sequestration [2]. The clear link between protein misfolding and disease highlights the importance of understanding this elaborate machinery that manages proteome homeostasis throughout evolution [31].

Mitochondria-Associated Degradation (MAD)

A specialized quality control pathway operates at the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM). Recent research has defined a unique MAD pathway comprised of a combination of cytosolic and mitochondrial factors that distinguish it from other cellular QC pathways [33]. This pathway degrades misfolded MOM proteins via the ubiquitin-proteasome system using temperature-sensitive model substrates in yeast.

Key findings from MAD studies include:

- Ubiquitination Mechanisms: The E3 ubiquitin ligases Ubr1 and San1 mediate substrate ubiquitination, with Ubr1 handling sen2-1HAts and San1 primarily ubiquitinating sam35-2HAts [33].

- Chaperone Requirement: MAD requires the SSA family of Hsp70s and the Hsp40 Sis1, providing the first evidence for chaperone involvement in mitochondrial outer membrane protein quality control [33].

- Extraction and Degradation: The Cdc48-Npl4-Ufd1 AAA-ATPase complex, along with Doa1 and a mitochondrial pool of the transmembrane Cdc48 adaptor Ubx2, are implicated in the degradation process [33].

Notably, when the proteasome is impaired, misfolded proteins accumulate on mitochondria, indicating they are not transported to other cellular locations for degradation [33].

Quality Control During Proteasome Assembly

An unexpected mechanism of spatial quality control has been identified during the assembly of the proteasome itself. Recent research reveals that a nuclear localization signal (NLS) within the proteasomal ATPase Rpt2 provides continuous surveillance throughout proteasome assembly [34]. This NLS-driven spatial control specifically sequesters defective assembly intermediates to the nucleus, away from ongoing assembly in the cytoplasm, thereby antagonizing defective proteasome formation [34].

This mechanism addresses a two-decade-old mystery regarding why proteasomal ATPases have NLSs despite being dispensable for nuclear localization of fully formed proteasomes [34]. The compartmentalization of assembly defects ensures that only correct proteasomes form, representing a sophisticated quality check that occurs throughout the assembly process rather than merely upon completion.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Experimental Models and Protocols

Live-Cell Microscopy for Tracking Protein Localization

Objective: To monitor the spatial distribution of quality control components and misfolded proteins in living cells.

- Reporter Design: Fluorescently tag chaperones (e.g., Nas6, Rpn14, Hsm3) or quality control substrates with GFP or mNeonGreen in their native chromosomal loci [34].

- Validation: Confirm that fluorescent tagging does not interfere with normal function through complementation assays [34].

- Localization Analysis: Track subcellular localization in wild-type versus mutant backgrounds under normal and stress conditions; calculate nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N/C) ratios to quantify redistribution [34].

- Colocalization Studies: Use known compartment markers (e.g., Pus1 for nucleus) to verify subcellular localization [34].

Mitochondria-Associated Degradation Assay

Objective: To define quality control pathways for misfolded mitochondrial outer membrane proteins.

- Substrate Design: Employ temperature-sensitive alleles of peripheral MOM proteins (e.g., sam35-2HAts and sen2-1HAts) that misfold at elevated temperatures (37°C) [33].

- Genetic Dissection: Systematically delete candidate quality control factors (chaperones, ubiquitin ligases, Cdc48 co-factors) and assess degradation kinetics.

- Degradation Monitoring: Measure substrate stability using cycloheximide chase assays followed by immunoblotting [33].

- Ubiquitination Detection: Confirm substrate ubiquitination through immunoprecipitation under denaturing conditions.

Visualization of Spatial QC Pathways

Diagram 1: Spatial QC Pathway Fate Decisions. This diagram illustrates the chaperone-mediated decision process that determines whether misfolded proteins are refolded, degraded, or spatially sequestered in specialized compartments.

Diagram 2: Proteasome Assembly QC. This diagram shows the quality control mechanism during proteasome assembly, where defective intermediates are sequestered to the nucleus via an NLS to prevent incorporation into proteasomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Spatial QC Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Spatial QC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Chaperones | Hsp70, Hsp40 (Sis1), Hsp90, Hsp110, TRiC/CCT | Recognize misfolded proteins, prevent aggregation, facilitate refolding or degradation [2] [33] |

| Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Components | E3 Ubiquitin Ligases (Ubr1, San1), Proteasome, Cdc48-Npl4-Ufd1 complex | Mediate ubiquitination and degradation of misfolded proteins [32] [33] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | GFP, mNeonGreen, mCherry | Tag proteins for live-cell imaging and tracking localization [34] |

| Temperature-Sensitive Mutants | sen2-1HAts, sam35-2HAts, other ts-alleles | Model substrates that misfold at specific temperatures to study QC pathways [33] |

| Compartment Markers | Pus1 (nuclear), various organelle markers | Verify subcellular localization in imaging studies [34] |

| Genetic Model Systems | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, C. elegans, mammalian cell culture | Comparative studies across species to identify conserved mechanisms [2] [33] |

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 3: Quantitative Metrics in Spatial QC Studies

| Experimental Condition | Measured Parameter | Value/Result | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Base Assembly (Wild-type yeast) | Nuclear/Cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio of chaperones (Nas6, Rpn14, Hsm3) | ~1 [34] | Base assembly intermediates remain cytoplasmic during normal assembly |

| Defective Base Assembly (hsm3Δ mutant) | N/C ratio of Nas6 | ~2 [34] | Defective assembly intermediates are enriched in the nucleus |

| Severely Defective Base Assembly (hsm3Δnas2Δrpn14Δ mutant) | N/C ratio of Nas6 | ~2.5 [34] | Increased defect severity correlates with greater nuclear enrichment |

| Biochar Impact on Soil Aggregates (2-year study) | Proportion of small aggregates (<0.25 mm) | Increased [35] | Biochar application alters soil aggregate structure, relevant to carbon sequestration |

| Biochar Impact on Soil Aggregates (2-year study) | Proportion of large aggregates (>0.25 mm) | Decreased [35] | Biochar alone reduces larger aggregate formation without plant roots |

| Consumer Protein Trends (2025 projection) | Consumers increasing protein intake | 61% (2024) vs 48% (2019) [36] | Context for applied research interest in protein biochemistry |

Evolutionary and Functional Implications

The conservation of spatial quality control mechanisms across eukaryotes highlights their fundamental importance in cellular homeostasis. In bacteria, protein quality control networks significantly influence molecular evolution by acting as master modifiers of the genotype-phenotype-fitness map [21]. Bacterial PQC components affect epistasis, evolvability, and the navigability of protein space, demonstrating how proteostasis shapes evolutionary trajectories [21].

Molecular chaperones accelerate the evolution of their protein clients in yeast, and the chaperone DnaK serves as a source of mutational robustness in bacteria [21]. These evolutionary perspectives provide crucial context for understanding how spatial quality control mechanisms have been shaped by, and in turn shape, evolutionary processes across species.

The compartmentalization of misfolded proteins represents a critical link to the pathogenesis of protein aggregation-linked diseases [31]. As the cellular capacity to manage the proteome declines during aging, the failure of spatial quality control mechanisms likely contributes to the late onset of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's diseases [2]. Understanding the comparative biology of these pathways across species thus provides not only fundamental insights into cellular evolution but also practical avenues for therapeutic development.

Model Systems and Innovative Approaches: Probing Protein Quality Control Mechanisms Experimentally

Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a Pioneering Model for PQC Discovery

The stability of the proteome, maintained by Protein Quality Control (PQC) systems, is fundamental to cellular health. Dysfunction in these systems is a hallmark of numerous human diseases, particularly neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease [2] [37]. The budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, has emerged as a pioneering and indispensable model organism for dissecting the intricate molecular mechanisms of PQC pathways. Its simplicity, combined with the profound evolutionary conservation of fundamental biological processes between yeast and humans, has enabled researchers to uncover and characterize core components of the cellular PQC network [38] [37]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of experimental approaches in yeast PQC research, detailing protocols, key reagents, and the specific advantages that make S. cerevisiae a powerful discovery engine for understanding how cells maintain proteostasis.

The Yeast PQC Toolkit: Core Machinery and Functions

Eukaryotic cells employ a multi-layered PQC strategy to manage misfolded proteins, involving refolding, degradation, and sequestration. The following table summarizes the core components of this system as elucidated through yeast studies.

Table 1: Core Protein Quality Control Machinery and Functions in S. cerevisiae

| PQC Component | Key Molecular Players | Primary Function in PQC |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Chaperones | Hsp70, Hsp90, Hsp40, TRiC/CCT, small HSPs [2] | Recognize misfolded proteins; facilitate refolding to native state; prevent aggregation. |

| Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) | E1/E2/E3 enzymes, 26S Proteasome [2] [33] | Tags irreversibly misfolded proteins with ubiquitin for degradation by the proteasome. |

| Mitochondria-Associated Degradation (MAD) | Ubr1, San1 (E3 Ligases); SSA Hsp70, Sis1; Cdc48-Npl4-Ufd1 [33] | Specialized UPS for misfolded proteins on the Mitochondrial Outer Membrane (MOM). |

| Spatial Sequestration | IPOD, JUNQ Quality Control Compartments [2] | Insoluble protein deposits (IPOD) and Juxtanuclear quality control (JUNQ) compartment sequester and aggregate toxic misfolded species. |

Advantages of S. cerevisiae as a PQC Model: A Comparative Analysis

The utility of S. cerevisiae for PQC discovery stems from a confluence of practical and biological factors that are not easily matched by other model systems.

Table 2: Comparative Advantages of S. cerevisiae for PQC Research

| Feature | Advantage in PQC Research | Comparison to Other Models |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Tractability | Easy gene knockouts, tagging, and overexpression enable functional dissection of PQC genes [37] [33]. | Superior to mammalian cells in speed and cost; more complex PQC network than bacteria. |

| Conservation with Humans | ~60% of yeast genes show homology to human genes; core PQC machinery is highly conserved [38] [37]. | Provides direct relevance, with many disease-associated human genes having functional yeast orthologs. |

| Rapid Growth & Low Cost | Short generation time (~1.5 hours) allows for high-throughput genetic and chemical screens [37]. | Enables experimental scales impractical in slower-growing, more expensive animal models. |

| Simplified Cellular Context | Reduces complexity for deciphering fundamental mechanisms, which can then be validated in mammalian systems [37]. | Lacks the specialized cell types of metazoans, but ideal for foundational cell biology. |

| Well-Defined Model Substrates | Temperature-sensitive mutants (e.g., sen2-1, sam35-2) provide controlled, physiologically relevant PQC substrates [33]. | Allows for synchronous induction of misfolding in specific cellular locales, unlike constitutive disease-associated aggregates. |

Key Experimental Protocols in Yeast PQC Research

Analyzing Mitochondria-Associated Degradation (MAD)

The Metzger et al. (2020) study established a robust protocol for defining a novel MAD pathway for misfolded peripheral proteins on the Mitochondrial Outer Membrane (MOM) [33].

- Step 1: Substrate Design. Utilize yeast strains expressing temperature-sensitive (ts-), epitope-tagged (e.g., HA) variants of MOM proteins, such as

sen2-1HAtsandsam35-2HAts. - Step 2: Misfolding Induction. Shift cultures from a permissive temperature (e.g., 25°C) to a restrictive temperature (37°C) to trigger synchronous substrate misfolding.

- Step 3: Degradation Assay. Monitor the turnover of the misfolded protein over time via cycloheximide chase assays and immunoblotting, comparing degradation kinetics between wild-type and mutant strains.

- Step 4: Genetic Dissection. Systematically delete or overexpress genes encoding putative PQC factors (E3 ligases like Ubr1, chaperones like Ssa1, Cdc48 co-factors) to quantify their effect on substrate stability and ubiquitination.

- Step 5: Localization Validation. Use cellular fractionation and microscopy to confirm the mitochondrial localization of the substrate and the degradation machinery, ensuring the process occurs at the MOM.

Modeling Human Neurodegenerative Disease Aggregates

Yeast has been extensively used to study the aggregation of proteins linked to human NDs, such as huntingtin (polyglutamine) and α-synuclein [37].

- Step 1: Heterologous Expression. Express the human disease-associated protein (e.g., a fragment of huntingtin with an expanded polyQ tract) in yeast under a controllable promoter.

- Step 2: Aggregate Detection. Visualize protein aggregation using fluorescence microscopy (if the protein is fused to a fluorophore like GFP) or biochemical methods like filter retardation assays.

- Step 3: Toxicity Screening. Assess the physiological impact of aggregation by monitoring yeast growth rates and viability.

- Step 4: Genetic Modifier Screening. Perform high-throughput genetic screens (e.g., using yeast knockout or overexpression libraries) to identify host factors that enhance or suppress aggregation and toxicity.

- Step 5: Pathway Analysis. Analyze the hits from the screen to map the cellular pathways, such as the Hsp70 chaperone system or the UPS, that are critical for managing the aggregating protein [2] [37].

Visualization of Key PQC Pathways and Workflows

Mitochondria-Associated Degradation (MAD) Pathway

This diagram illustrates the specialized protein quality control pathway for misfolded proteins on the mitochondrial outer membrane, as defined in yeast [33].

Experimental Workflow for PQC Discovery in Yeast

This flowchart outlines a generalized experimental strategy for discovering and characterizing Protein Quality Control mechanisms using S. cerevisiae as a model system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

A successful yeast PQC study relies on a well-characterized set of biological tools and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Yeast PQC Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature-Sensitive (ts-) Alleles | Conditionally misfolded proteins that enable controlled, synchronous induction of PQC substrates within their native cellular context [33]. | sen2-1HAts and sam35-2HAts for studying Mitochondria-Associated Degradation (MAD) [33]. |

| Heterologous Disease Proteins | Human neurodegenerative disease-associated proteins (e.g., Htt-polyQ, α-synuclein) expressed in yeast to model aggregation and toxicity [37]. | Studying the role of chaperones like Hsp70 in suppressing the toxicity of Huntingtin protein aggregates [2]. |

| Yeast Deletion/Overexpression Libraries | Genome-wide collections of yeast strains, each with a single gene deleted or overexpressed, for unbiased genetic screening. | Identifying which host genes modify the aggregation or toxicity of a expressed human disease protein [37]. |

| Chaperone-Specific Inhibitors/Modulators | Chemical compounds (e.g., radicicol) that inhibit specific chaperone functions to probe their role in PQC pathways. | Testing the requirement for Hsp90 in the refolding or degradation of a specific misfolded substrate. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Compounds (e.g., MG-132) that block proteasomal activity, used to confirm UPS-dependent degradation of a substrate. | Accumulation of a ubiquitinated protein upon MG-132 treatment provides evidence for its proteasomal targeting [33]. |

Saccharomyces cerevisiae continues to be a powerful and versatile discovery platform for deconstructing the complex biology of protein quality control. Its unique combination of experimental tractability, conserved core machinery, and proven utility in modeling human disease processes makes it an ideal system for both foundational discovery and pre-clinical investigation. The protocols, tools, and pathways defined in yeast provide an essential framework for understanding proteostasis in health and disease across the eukaryotic lineage, guiding therapeutic development for a wide range of conformational diseases.

Temperature-Sensitive Misfolding Proteins as Versatile PQC Reporters

Temperature-sensitive (Ts) misfolding proteins represent a powerful class of molecular reporters for dissecting protein quality control (PQC) pathways. These tools enable researchers to induce and track protein misfolding with precise temporal control, providing critical insights into proteostasis mechanisms from yeast to human models. This guide compares the performance and applications of key Ts reporters, detailing their experimental utilization and highlighting how they reveal conserved and divergent PQC strategies across species. We present standardized protocols and analytical frameworks to facilitate the selection of appropriate reporters for specific research objectives in fundamental biology and drug development.

Protein quality control machinery constitutes a fundamental cellular defense network against proteotoxicity associated with neurodegenerative diseases and aging [2] [39]. Temperature-sensitive misfolding proteins serve as ideal experimental tools for probing this network because they mimic pathological misfolding while offering precise temporal control through simple temperature shifts [40] [41]. Unlike constitutively misfolded proteins that chronically stress PQC systems, Ts variants enable researchers to initiate the misfolding process synchronously, allowing precise monitoring of subsequent cellular handling including recognition, refolding attempts, aggregation, sequestration, and degradation [40].

These reporters are particularly valuable in the model organism Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where they have revealed evolutionary conserved spatial PQC pathways that sequester misfolded proteins into specific quality control compartments such as the Juxtanuclear Quality Control (JUNQ), Insoluble Protein Deposit (IPOD), and intranuclear quality control sites [40] [41] [42]. The non-toxic nature of well-characterized Ts reporters allows investigation of PQC mechanisms without triggering severe stress responses that could complicate interpretation, making them superior tools for analyzing fundamental proteostasis principles [40].

Comparative Analysis of Key Ts Misfolding Reporters

Performance Characteristics of Established Reporters

Table 1: Comparison of Key Temperature-Sensitive Misfolding Reporters

| Reporter Protein | Native Function | Aggregation Propensity | Clearance Kinetics | Hsp104 Recruitment | Colocalization with PQC Sites | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| guk1-7 | Guanylate kinase | Moderate (aggregates at 30°C & 38°C) | Slow | Efficient | Strong (JUNQ/IPOD) | Non-toxic |