Essential Quality Control for Recombinant Proteins: A Practical Guide to Improve Research Reproducibility

This article provides a comprehensive framework for implementing minimal quality control (QC) tests for recombinant protein samples, targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Essential Quality Control for Recombinant Proteins: A Practical Guide to Improve Research Reproducibility

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for implementing minimal quality control (QC) tests for recombinant protein samples, targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It addresses the critical need for standardized QC practices to combat the high economic and scientific costs of irreproducible research data. The content spans from foundational principles and the economic impact of poor protein quality to detailed methodological protocols for purity, homogeneity, and identity assessment. It further delivers practical troubleshooting strategies for common issues like aggregation and instability, and concludes with guidelines for validating method performance and comparing results against established standards, empowering laboratories to ensure their protein reagents are reliable and fit-for-purpose.

Why Protein QC is Non-Negotiable: The Foundation of Reproducible Science

The Reproducibility Crisis in Preclinical Research and the Role of Protein Reagents

The reproducibility of preclinical research is a foundational pillar of biomedical innovation, yet it is facing a significant crisis. A growing number of studies fail to replicate across laboratories, undermining the reliability of scientific findings and their translation to human health and drug development [1]. This crisis has quantifiable economic impacts; one estimate suggests that $28 billion per annum in US research is attributable to irreproducible preclinical experiments, with $10.4 billion of this directly attributed to poor quality 'biological reagents and reference materials' [2]. Among these critical reagents, proteins and peptides are widely used yet often represent a hidden source of variability and error. The use of inadequately characterized protein reagents can lead to a cascade of irreproducible results, compromising everything from basic research findings to drug development pipelines [2]. This Application Note frames this challenge within the context of a broader thesis on establishing minimal quality control (QC) tests for recombinant protein samples, providing researchers and drug development professionals with structured data and detailed protocols to enhance the reliability of their work.

Quantitative Data on Reagent-Related Irreproducibility

The scale of the problem is evidenced by several high-profile studies. Attempts to replicate published preclinical research have shown alarmingly low success rates. Scientists at Bayer Healthcare and Amgen found that ~65% to ~89% of published studies could not be replicated, a quantification higher than previously expected [3]. A more recent study placed this figure closer to 50%, which still indicates a systemic issue [3]. The following table summarizes key data on the economic and scientific impact of the reproducibility crisis, with a specific focus on reagent quality.

Table 1: Quantifying the Impact of the Reproducibility Crisis

| Aspect of Crisis | Quantitative Finding | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Irreproducible Preclinical Research (US) | ~50% of experiments ($28 Billion/yr) | Freedman et al. (2015) analysis of 2012 data [2] |

| Attribution to Biological Reagents | 36% of total ($10.4 Billion/yr) | Freedman et al. (2015) [2] |

| Antibody-Specific Economic Waste (US) | $0.4 - $1.8 Billion/yr | Ayoubi et al. (2023), Bradbury and Plückthun (2015) [4] |

| Failure Rate of Commercial Antibodies | ~50% fail basic characterization | Bradbury and Plückthun (2015), Baker (2015) [5] [4] |

| Landmark Study Replication Failures | 47 of 53 studies failed to replicate | Begley and Ellis (2012) cancer biology studies [6] |

| Replication of Positive Effects | 40% successful replication rate | Errington et al. (2021) [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Ensuring the quality of protein reagents requires a set of essential materials and methods. The following table outlines key solutions and their functions that researchers should integrate into their workflows to mitigate reproducibility issues.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Quality Control

| Item / Solution | Function & Importance in QC |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Antibodies | Defined by their genetic sequence; produced in stable cell lines (e.g., HEK293) to ensure lot-to-lot consistency and superior specificity compared to traditional hybridoma-based monoclonals or polyclonals [5] [4]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Assesses protein homogeneity and dispersity (oligomeric state, presence of aggregates). Sample poly-dispersity can indicate instability and lead to overestimation of active protein concentration [2] [7]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Confirms protein identity (via mass fingerprinting or tryptic digests) and intactness (via intact protein mass). Critical for verifying the correct protein and detecting proteolysis or truncations [2]. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Evaluates protein oligomeric state and purity. When coupled with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS), it provides a robust assessment of molecular mass and homogeneity [2] [7]. |

| Digital Home Cage Monitoring (e.g., JAX Envision) | A transformative approach for in vivo studies; enables continuous, non-invasive observation of animals, minimizing human interference and capturing unbiased physiological and behavioral data, thereby enhancing replicability [1]. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Software platform that supports QA/QC by ensuring proper documentation, sample traceability, chain of custody, and compliance with regulatory standards (e.g., 21 CFR Part 11, ISO 17025) throughout the product lifecycle [8]. |

| Antibodypedia / Human Protein Atlas | Searchable databases providing characterization data for antibodies, aiding researchers in selecting well-validated reagents for their specific applications [5] [4]. |

Proposed Minimal QC Guidelines for Recombinant Proteins

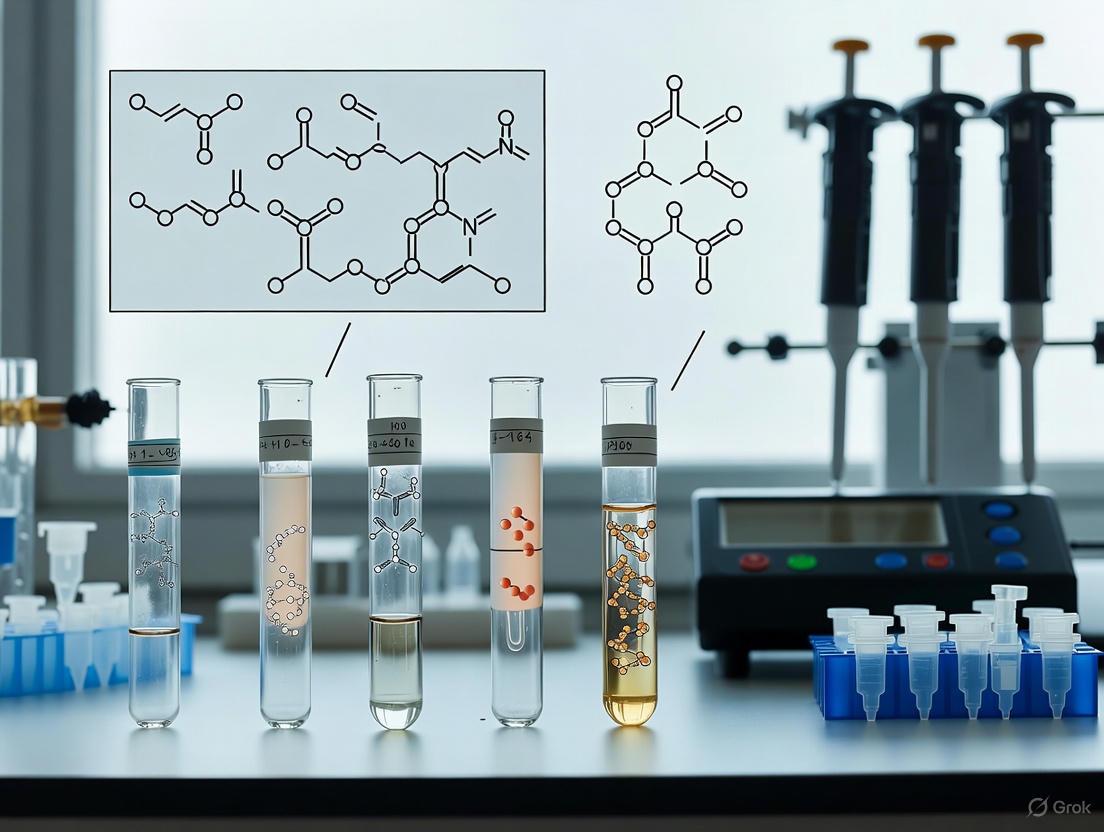

To address these challenges, expert consortia like the ARBRE-MOBIEU and P4EU networks have proposed a Minimal Protein Quality Standard (PQS) [2] [9]. The guidelines are designed to be implemented using simple, widely available experimental methods and are divided into three parts: Minimal Information, Minimal QC Tests, and Extended QC Tests. The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for recombinant protein production and quality control.

Diagram 1: Protein QC Workflow

Minimal Information Requirements

For any recombinant protein used in research, the following information must be documented to ensure the experiment can be accurately reproduced [2]:

- Complete Construct Sequence: The full sequence of the recombinant construct must be made available, and the sequence should be confirmed after cloning to avoid wasteful production trials.

- Expression, Purification, and Storage Conditions: These conditions must be fully described to enable accurate reproduction in any laboratory.

- Protein Concentration Measurement Method: The specific method used for determining protein concentration (e.g., BCA, Bradford, A280) must be stated.

Minimal QC Tests: Detailed Protocols

The following minimal QC tests are proposed as essential for validating any recombinant protein reagent [2] [7].

Protocol 4.2.1: Assessing Protein Purity

Principle: Protein purity is critical as contaminants can lead to artefactual results in downstream applications. This protocol uses SDS-PAGE, a widely accessible method, to assess purity.

- Materials: Protein sample, SDS-PAGE gel (appropriate percentage), electrophoresis system, protein molecular weight marker, Coomassie Brilliant Blue or silver stain.

- Procedure:

- Dilute an appropriate amount of protein sample (e.g., 1-5 µg) in 1X SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

- Heat the sample at 95°C for 5 minutes to denature the proteins.

- Load the sample and a pre-stained protein ladder onto the SDS-PAGE gel.

- Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 120-150V) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel.

- Stain the gel with Coomassie Blue to visualize protein bands.

- Data Interpretation: A single major band at the expected molecular weight indicates high purity. The presence of multiple bands or smearing suggests contamination, proteolysis, or aggregation. Densitometric analysis can provide a quantitative estimate of purity percentage. For higher sensitivity and detection of minor truncations, Capillary Electrophoresis (CE), Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC), or Mass Spectrometry (MS) are recommended [2].

Protocol 4.2.2: Assessing Homogeneity/Dispersity

Principle: This test determines the size distribution and oligomeric state of the protein sample, which is vital for functional assays. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) is a rapid, non-destructive method for this purpose.

- Materials: Purified protein sample, DLS instrument, suitable cuvette, buffer for dialysis/dilution (must be particle-free and matched to storage buffer).

- Procedure:

- Clarify the protein sample by centrifugation at >14,000 x g for 10-15 minutes to remove any large aggregates or dust.

- Carefully pipette the supernatant into a clean, dust-free DLS cuvette, avoiding the introduction of bubbles.

- Place the cuvette in the instrument and set the measurement temperature (typically 4°C, 20°C, or 25°C).

- Run the measurement according to the manufacturer's instructions. Typically, 10-15 acquisitions are averaged.

- Data Interpretation: A monodisperse sample will show a single, sharp peak in the size distribution plot. A polydisperse profile with multiple peaks indicates a mixture of species (e.g., monomers, dimers, aggregates), which can dramatically affect downstream results like enzyme kinetics [2]. As an orthogonal method, Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) is highly recommended, with SEC-MALS being the gold standard [2] [7].

Protocol 4.2.3: Confirming Protein Identity

Principle: Confirming that the purified protein is the intended target is a fundamental QC step. "Bottom-up" MS via mass fingerprinting is a highly specific method for this.

- Materials: Purified protein sample, trypsin or other proteolytic enzyme, mass spectrometer (MALDI-TOF or ESI-MS/MS), suitable buffer.

- Procedure:

- Run a small amount of protein on SDS-PAGE and excise the band of interest (optional but common for in-gel digestion).

- Reduce, alkylate, and digest the protein with trypsin overnight.

- Extract the resulting peptides from the gel and desalt.

- Mix the peptide sample with a matrix (for MALDI-TOF) and spot it on a target plate, or inject directly into an ESI-MS/MS system.

- Acquire a mass spectrum of the peptides.

- Data Interpretation: The list of observed peptide masses (mass fingerprint) is compared against a theoretical digest of the expected protein sequence using database search software (e.g., Mascot, Sequest). A statistically significant match confirms the protein's identity. For direct confirmation and detection of any mass alterations (e.g., truncations, modifications), "top-down" MS analysis of the intact protein is performed [2].

Case Study & Advanced Considerations

The Critical Role of Protein Quantification

Accurate protein quantification is a cornerstone of reproducible research, yet conventional methods can be unreliable, especially for transmembrane proteins. A 2024 study systematically compared common quantification methods (Lowry, BCA, Bradford) with a newly developed indirect ELISA for quantifying Na,K-ATPase (NKA), a large transmembrane protein [10]. The results revealed that the conventional methods significantly overestimated the concentration of NKA compared to the ELISA. When these inaccurate concentrations were applied to in vitro assays, the data variation was consistently low only when reactions were prepared using concentrations determined by the specific ELISA [10]. This highlights that for critical applications and non-standard proteins, reliance on generic colorimetric assays is insufficient, and specific quantification methods like ELISA are necessary.

The Antibody Characterization Crisis

The reproducibility crisis is profoundly linked to antibodies, which are themselves protein reagents. It is estimated that ~50% of commercial antibodies fail to meet basic characterization standards [5] [4]. The problems include batch-to-batch variation, non-specific binding, and in some cases, antibodies marketed for one protein actually recognizing another, leading to wasted years of research and millions of dollars [5]. A key recommendation is to distinguish between antibody characterization (describing an antibody's inherent ability to perform in different assays) and validation (confirming a specific antibody lot performs as needed in a researcher's specific experimental context) [4]. The scientific community is urged to move towards recombinant antibodies, defined by their sequence, as they offer a path to permanent standardization and superior lot-to-lot consistency [5] [4].

The reproducibility crisis in preclinical research demands a systematic and vigilant approach to the quality of all research reagents, with protein reagents being of paramount importance. The implementation of the Minimal Protein Quality Standard (PQS)—entailing the reporting of minimal information and the performance of minimal QC tests for purity, homogeneity, and identity—provides a practical and actionable framework for individual researchers, core facilities, and commercial vendors [2] [9]. By adopting these guidelines, meticulously documenting procedures, and moving towards better-defined reagents like recombinant antibodies, the scientific community can significantly enhance the reliability and reproducibility of preclinical data. This, in turn, will strengthen the entire translational pipeline, accelerating the development of effective therapies and restoring confidence in biomedical research.

In the fast-paced world of biomedical and life science research, groundbreaking discoveries fuel medical advancements and technological innovation. However, a critical issue threatens the integrity of scientific progress: irreproducibility [11]. Studies suggest that over 50% of preclinical research is irreproducible, leading to an estimated financial loss of $28 billion annually in the U.S. alone [11]. This crisis not only wastes valuable resources but also delays life-saving treatments, endangers patients in clinical trials, and undermines public trust in science [12] [11]. For researchers working with recombinant proteins—complex molecules vital to modern biologics—the implications are particularly severe. Inconsistent protein samples can derail experiments, invalidate drug discovery efforts, and contribute to this massive economic burden. This Application Note examines the profound costs of irreproducible data and provides a foundational framework of minimal quality control (QC) tests to enhance the reliability of recombinant protein research, thereby protecting scientific and financial investments.

Table 1: The Economic Burden of Irreproducible Research in the United States

| Aspect of Cost | Estimated Financial Impact | Key References |

|---|---|---|

| Total Annual Direct Cost | $28 billion | [13] [12] [11] |

| Range of Indirect Costs | $13.5 billion to $270 billion annually | [12] |

| Cost of Poor Data Quality (All Industries) | $12.9 million per organization annually | [14] |

| Potential Savings from Open Data (Oncology) | Up to $1.26 billion | [12] |

The High Price of Irreproducibility

Economic and Scientific Consequences

Irreproducible research creates a cascade of negative outcomes that extend far beyond the laboratory. The direct economic impact, estimated at $28 billion annually in the U.S., represents wasted resources that could otherwise support promising studies and genuine innovation [13] [12] [11]. This figure primarily encompasses squandered research funding, but the true cost is likely much higher when considering indirect effects. A "house of cards" scenario, where subsequent studies are built upon faulty foundational research, may inflate the total economic impact to a staggering $270 billion annually [12].

The consequences are not merely financial. Irreproducibility undermines the core scientific principle of validation through replication, misleading entire fields and stunting genuine progress [11]. In the pharmaceutical industry, companies frequently suffer massive losses by investing in drug development pipelines based on irreproducible preclinical findings. Medications such as Prempro, Xigris, and Avastin were approved despite pivotal clinical trials that later studies failed to reproduce [12]. When these drugs demonstrate little efficacy or are withdrawn for safety reasons, the result is monumental financial loss and a setback for patients in need of effective therapies.

Human and Ethical Costs

Perhaps the most devastating consequence of irreproducibility is its impact on patient care. Clinical decisions and human trials are often predicated on preclinical research; when the foundational science is unreliable, it directly jeopardizes patient safety [11]. Historical cases, like that of high-dose chemotherapy plus bone marrow transplants (HDC/ABMT) for breast cancer in the 1980s and 90s, underscore this grave risk. Initial speculative studies spurred $1.75 billion in flawed clinical trials and 35,000 failed treatments, causing serious side effects in thousands of patients for no survival benefit [12]. Each irreproducible study in the recombinant protein pipeline not only wastes resources but also potentially delays the arrival of life-saving treatments for cancer, rare genetic diseases, and chronic illnesses for which biologics are often the last hope.

Root Causes of Irreproducibility in Recombinant Protein Research

The problem of irreproducibility stems from several interconnected factors, many of which are acutely relevant to the production and analysis of recombinant proteins.

- Methodological Flaws: Poorly designed studies, inadequate controls, and a lack of standard operating procedures (SOPs) lead to inconsistent methodologies across labs [11]. For recombinant proteins, this can include vast differences in expression, purification, and handling protocols.

- Statistical Issues & Publication Bias: The misuse of statistical analyses (e.g., p-hacking) and the selective reporting of only positive outcomes create an inaccurate picture of scientific findings [11]. Researchers face intense pressure to publish novel, groundbreaking results, which discourages the vital work of replication studies [12] [11].

- Biological Variability and Lack of Standardization: Differences in cell lines, reagents, and undocumented environmental variables (e.g., lab temperature, storage conditions) make replicating experiments notoriously challenging [11]. A recombinant protein produced in different host systems (e.g., mammalian vs. bacterial) or with reagents from different suppliers can have significantly different post-translational modifications and functional properties [11].

- The Challenge of "Analytical Debt": In data analytics, there is a growing recognition of "analytical debt," a hidden liability that accumulates when irreproducible results are accepted because they "look right" [14]. This debt, like technical debt in software, grows silently until it demands payment—often as emergency troubleshooting, delayed decisions, or eroded trust. This concept is directly analogous to accepting protein sample quality based on a single, unverified assay, a risk that can undermine an entire research program months or years later.

A Minimal QC Framework for Recombinant Protein Samples

Implementing a minimal battery of QC tests at the point of receipt or production of a recombinant protein sample can prevent irreproducibility at its source. The following protocol outlines four essential assays that together provide a comprehensive snapshot of protein integrity, quantity, and identity.

Experimental Workflow for Minimal QC

The following diagram visualizes the logical workflow for the minimal QC tests described in this protocol, ensuring a standardized and sequential approach to characterizing recombinant protein samples.

Protocol 1: Purity and Molecular Weight Assessment by SDS-PAGE

1.1 Principle: This method separates proteins based on their molecular weight under denaturing conditions, providing information about sample purity, the presence of degradation products, or contaminating proteins.

1.2 Materials:

- Precast polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 4-20% gradient gel)

- SDS-PAGE running buffer

- Protein molecular weight marker

- Heating block

- Gel electrophoresis apparatus

- Staining solution (e.g., Coomassie Blue or SYPRO Ruby) and destaining solution (if required)

1.3 Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute 10-20 µg of the recombinant protein sample in 1X Laemmli buffer.

- Denaturation: Heat the mixture at 95°C for 5 minutes.

- Loading: Briefly centrifuge the samples and load them into the wells of the gel. Include a well for the molecular weight marker.

- Electrophoresis: Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 120-150V) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel.

- Visualization: Stain the gel with an appropriate stain (e.g., Coomassie Blue for 1 hour) followed by destaining until clear bands are visible against a clean background.

1.4 Expected Results & Analysis: A pure protein sample should show a single, predominant band at the expected molecular weight. Multiple bands suggest contamination or degradation, while a smeared appearance may indicate protein aggregation or proteolysis.

Protocol 2: Concentration Determination by A280 Absorbance

2.1 Principle: The concentration of a protein solution can be determined by measuring its absorbance at 280 nm, which is primarily due to its tyrosine, tryptophan, and phenylalanine content.

2.2 Materials:

- UV-Visible spectrophotometer with UV light source

- Quartz cuvette suitable for UV measurements

- Dilution buffer (e.g., PBS or the protein's storage buffer)

2.3 Procedure:

- Blank Instrument: Using a cuvette filled with dilution buffer, blank the spectrophotometer at 280 nm.

- Measure Absorbance: Replace the blank with the protein sample (appropriately diluted if necessary) and record the absorbance at 280 nm. Ensure the absorbance reading falls within the linear range of the instrument (typically 0.1 - 1.0).

- Calculate Concentration: Apply the Beer-Lambert law: Concentration (mg/mL) = A280 / (ε * l), where ε is the protein's extinction coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) and l is the pathlength in cm. For a quick estimate, a general factor of 1.0 A280 ≈ 1 mg/mL can be used for many proteins, but this is less accurate.

2.4 Expected Results & Analysis: This provides a quantitative measure of the protein concentration, which is critical for normalizing downstream functional assays. Inconsistent results across different batches can signal issues with production or storage.

Protocol 3: Identity and Specificity Confirmation by Western Blot

3.1 Principle: Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE are transferred to a membrane and probed with a specific antibody, confirming the protein's identity based on antibody-antigen interaction.

3.2 Materials:

- Nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane

- Transfer apparatus and buffer

- Primary antibody specific for the recombinant protein

- HRP-conjugated secondary antibody

- Chemiluminescent substrate

- Blocking buffer (e.g., 5% non-fat milk in TBST)

3.3 Procedure:

- Transfer: Following SDS-PAGE, transfer the separated proteins from the gel to a membrane using a wet or semi-dry transfer system.

- Blocking: Incubate the membrane in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature to prevent non-specific antibody binding.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate the membrane with the primary antibody (diluted in blocking buffer) for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Washing: Wash the membrane 3 times for 5 minutes each with TBST buffer.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Incubate the membrane with the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (diluted in blocking buffer) for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Washing: Repeat the washing step as above.

- Detection: Incubate the membrane with chemiluminescent substrate and image using a digital imager.

3.4 Expected Results & Analysis: A single band at the expected molecular weight confirms the protein's identity. Non-specific bands may indicate antibody cross-reactivity or the presence of protein contaminants.

Protocol 4: Functional Activity Screening by ELISA

4.1 Principle: This assay verifies the protein's functional capacity, such as its ability to bind to a specific target ligand or receptor, providing a critical check of its folded, native state.

4.2 Materials:

- 96-well microplate

- Target ligand or capture antibody

- Coating buffer (e.g., carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6)

- Washing buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween-20)

- Detection antibody (if using a sandwich format)

- HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and colorimetric/chemiluminescent substrate

- Plate reader

4.3 Procedure (Sandwich ELISA Example):

- Coat Plate: Adsorb the capture antibody or target ligand to the plate overnight at 4°C.

- Blocking: Block the plate with a protein-based blocking buffer for 1-2 hours.

- Apply Sample: Add the recombinant protein sample (serially diluted) to the wells and incubate for 1-2 hours.

- Washing: Wash the plate 3-5 times with washing buffer.

- Detection Antibody: Add a detection antibody specific to the recombinant protein and incubate.

- Secondary Antibody: Add an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and incubate.

- Washing: Repeat the washing step.

- Substrate & Readout: Add the enzyme substrate and measure the resulting signal with a plate reader.

4.4 Expected Results & Analysis: A dose-dependent increase in signal confirms the protein's specific binding functionality. A loss of binding signal compared to a reference standard suggests the protein may be misfolded, denatured, or degraded.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A reliable and consistent supply of key reagents is fundamental to achieving reproducible results. The following table details essential materials for the QC protocols featured in this note.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Recombinant Protein QC

| Reagent / Solution | Primary Function in QC | Key Considerations for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Specific detection of the target protein in Western Blot and ELISA. | Use antibodies that have been validated for the specific application (e.g., Western). Consistent supplier and lot-to-lot validation are critical. |

| Protein Molecular Weight Markers | Accurate estimation of protein size in SDS-PAGE and Western Blot. | Choose a marker with a range that brackets your protein's expected size. |

| Spectrophotometer Qualification Kit | Verifies the accuracy and precision of the spectrophotometer used for A280 concentration assays. | Regular qualification according to manufacturer guidelines ensures concentration data is reliable. |

| Chemiluminescent Substrate | Sensitive detection of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugates in Western Blot. | Consistent substrate formulation and development time are key for comparable signal intensity across experiments. |

| Cell Culture Media & Supplements | Production of recombinant protein in mammalian, insect, or bacterial host cells. | Serum batch variability can significantly impact protein yield and quality. Where possible, use defined, serum-free media. |

The staggering economic cost of irreproducible data, estimated at over $28 billion annually in the U.S. alone, is a systemic crisis demanding immediate and systematic action [13] [11]. For researchers in the critical field of recombinant protein science, the adoption of a minimal QC framework is not a luxury but an economic and ethical necessity. The foundational protocols outlined here—SDS-PAGE, A280 quantification, Western Blot, and a functional ELISA—provide a accessible, yet powerful, first line of defense against the propagation of unreliable data. By routinely implementing these standardized quality checks, the scientific community can reclaim wasted resources, accelerate the pace of genuine discovery, and ensure that the promising field of biologics fulfills its potential to deliver life-changing therapies. Building reproducibility into the architectural foundation of research, rather than treating it as an afterthought, is the most effective strategy for transforming analytical debt into lasting scientific capital.

In the realm of recombinant protein research, the quality of protein reagents is a fundamental determinant of experimental success and data reproducibility. A tiered quality control (QC) framework, categorizing tests into 'Minimal' and 'Extended' levels, provides a rational strategy to balance scientific rigor with practical resource allocation. Widespread use of poorly characterized proteins has contributed to a significant reproducibility crisis in preclinical research; one analysis attributes a staggering $10.4 billion annually in US research costs directly to poor quality biological reagents and reference materials [15] [2]. This application note establishes a structured, practical framework for implementing a tiered QC approach, enabling researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to ensure the reliability of their recombinant protein samples while aligning QC efforts with specific application goals.

A Tiered QC Framework: Minimal and Extended Levels

The proposed framework, developed by expert consortia such as ARBRE-MOBIEU and P4EU, organizes QC tests into two primary tiers [15] [2] [9]. This structure guides researchers from essential verification to comprehensive characterization.

Core Philosophy and Workflow Logic

The decision to perform minimal or extended QC is driven by the protein's intended application and the required depth of characterization. The logical workflow progresses from basic confirmation to in-depth analysis, ensuring resource investment is proportionate to the criticality of the protein's role in research or development.

Detailed QC Tiers: Tests, Methods, and Applications

Minimal Information and QC Tests

The Minimal level constitutes the non-negotiable foundation of protein QC. It requires documenting essential information and performing three core tests to verify basic integrity and composition.

Mandatory Minimal Information to Document [15] [2]:

- Construct Sequence: The complete amino acid sequence of the recombinant construct, verified by DNA sequencing.

- Production Protocol: Detailed expression, purification, and storage conditions to enable replication.

- Concentration Method: The specific technique used for measuring protein concentration.

Mandatory Minimal QC Tests [15] [2]:

Table 1: Minimal QC Tests for Recombinant Proteins

| QC Test | Objective | Recommended Techniques | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purity | Assess sample homogeneity and detect contaminants (e.g., other proteins, proteolytic fragments). | SDS-PAGE, Capillary Electrophoresis (CE), Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC). | A single major band at correct molecular weight on SDS-PAGE (≥90% purity); minimal contaminant peaks in chromatograms. |

| Homogeneity/ Dispersity | Evaluate oligomeric state and aggregate presence, indicating structural correctness and stability. | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC). | A monodisperse population with a polydispersity index (PDI) < 0.2 in DLS; a single, symmetric peak in SEC corresponding to the expected oligomer. |

| Identity | Confirm the protein's identity and intactness, ruling out purification of incorrect host proteins. | Bottom-up MS (mass fingerprinting), Top-down MS (intact protein mass). | Measured mass matches theoretical mass within instrument error (e.g., < 5 ppm for high-resolution MS); peptide fragments map to expected sequence. |

Extended QC Tests

Extended QC tests provide a deeper understanding of protein function and stability. These are selectively applied based on the protein's intended downstream application.

Table 2: Extended QC Tests for Recombinant Proteins

| QC Test | Objective | Recommended Techniques | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Folding State/ Structural Integrity | Confirm the protein is correctly folded into its native, functional conformation. | Circular Dichroism (CD), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC). | Proteins for structural studies, ligand-binding assays, and functional enzymology. |

| Specific Activity | Measure functional potency per unit mass of protein. | Enzyme activity assays, cell-based bioassays, ligand binding assays (SPR, BLI). | Therapeutic enzyme production, catalytic studies, and any application where function is critical. |

| Endotoxin Testing | Detect and quantify bacterial lipopolysaccharides. | Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay. | Essential for proteins produced in E. coli destined for cell culture or in vivo applications. |

| Advanced Mass Analysis | Detect fine micro-heterogeneity (e.g., post-translational modifications, minor truncations). | High-resolution Mass Spectrometry (MS). | Critical for proteins where PTMs (e.g., glycosylation, phosphorylation) affect activity. |

Experimental Protocols for Key QC Tests

Protocol: Assessing Purity and Identity by SDS-PAGE and MS

This integrated protocol uses SDS-PAGE for rapid purity assessment followed by mass spectrometry for definitive identity confirmation [15] [2].

I. Materials & Reagents

- Protein Sample: Purified recombinant protein in suitable buffer.

- SDS-PAGE System: Precast polyacrylamide gel, electrophoresis cell, power supply.

- Staining Solution: Coomassie Blue or SYPRO Ruby protein gel stain.

- Mass Spectrometer: MALDI-TOF or LC-ESI-MS system.

- Digestion Reagents: Trypsin, ammonium bicarbonate, dithiothreitol (DTT), iodoacetamide.

II. Procedure

- Sample Denaturation: Mix 5-20 µg of protein with 1X Laemmli SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Heat at 95°C for 5 minutes.

- Electrophoresis: Load samples and a pre-stained protein ladder onto the gel. Run at constant voltage (e.g., 120-150V) until the dye front reaches the bottom.

- Staining & Analysis: Stain the gel with Coomassie Blue. Destain and image. The sample should show a single dominant band at the expected molecular weight. Minor bands should constitute <10% of total staining.

- In-Gel Digestion (for Bottom-Up MS): Excise the protein band of interest. Destain, reduce with DTT, and alkylate with iodoacetamide. Digest with trypsin overnight at 37°C.

- Peptide Extraction: Extract peptides from the gel piece with acetonitrile and trifluoroacetic acid. Dry down the extract in a vacuum concentrator.

- MS Analysis: Reconstitute peptides in MS-compatible solvent and analyze by LC-MS/MS. Search fragment ion spectra against a protein database to confirm identity.

Protocol: Evaluating Homogeneity by Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

SEC separates proteins based on their hydrodynamic radius, providing information about oligomeric state and the presence of aggregates [15].

I. Materials & Reagents

- SEC System: HPLC or FPLC system with UV detector.

- SEC Column: Suitable for the protein's molecular weight range (e.g., Superdex 200 Increase for proteins 10-600 kDa).

- Running Buffer: A volatile, MS-compatible buffer is recommended if collecting fractions for further analysis.

II. Procedure

- System Equilibration: Equilibrate the SEC column with at least 2 column volumes of running buffer at a constant flow rate (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mL/min).

- Sample Preparation & Injection: Centrifuge the protein sample (e.g., 10,000 x g, 10 min) to remove any particulate matter. Inject 50-100 µL of sample.

- Chromatogram Acquisition: Monitor the UV absorbance at 280 nm. The resulting chromatogram will show peaks corresponding to different species in the sample.

- Data Interpretation: A homogeneous, monodisperse preparation will result in a single, symmetric peak at an elution volume corresponding to the expected oligomeric state. The presence of aggregates appears as peaks at the void volume, while fragments or degraded protein elute later.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful QC workflow relies on specific reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions for effective protein quality control.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Protein QC

| Item | Function/Description | Application in QC Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Protein Ladders | A mixture of proteins of known molecular weight. | Acts as a reference for determining approximate molecular weight in SDS-PAGE analysis. |

| iRT Peptides | A set of synthetic peptides with known, stable retention times. | Used in LC-MS systems as internal retention time standards for chromatographic performance monitoring and normalization [16] [17]. |

| Dynamic Range Protein Mixtures | A defined mixture of proteins at known, varying concentrations (e.g., NIST RM 8323, Sigma UPS1). | Serves as a system suitability and instrument QC sample to assess sensitivity, dynamic range, and quantitative accuracy of the MS platform [16] [17]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Peptides or proteins synthesized with heavy isotopes (e.g., 13C, 15N). | Used as internal standards in targeted MS (e.g., PRM, SRM) for precise and accurate quantification, correcting for sample preparation and instrument variability [16]. |

| Reference Protein Materials | Well-characterized, high-purity protein samples (e.g., BSA digest). | Used as a process control to evaluate sample preparation consistency and digestion efficiency across batches [17]. |

Implementing this tiered QC framework is a critical step toward restoring robustness and reproducibility in research involving recombinant proteins. The "Minimal" QC tests provide a vital baseline for all protein reagents, while the "Extended" tests offer a pathway to deeper characterization for critical applications. Researchers are encouraged to integrate these practices into their standard operating procedures. Furthermore, to foster transparency and collective progress, detailed QC data—including the minimal information and results from relevant tests—should be included in manuscript submissions and shared within the scientific community [15] [2] [9]. Adopting this disciplined, tiered approach ensures that protein quality becomes a solid foundation for discovery, rather than a source of error.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the reliability of experimental data and the success of biopharmaceutical products hinge on the quality of the recombinant protein reagents used. In both academic research and industrial bioprocessing, a minimal quality control (QC) package is not merely beneficial—it is essential for ensuring data reproducibility, validating experimental findings, and meeting regulatory standards [2]. The core components of this package universally agreed upon are Identity, Purity, and Homogeneity [2] [9].

These guidelines are based on established protein quality standards proposed by expert networks such as ARBRE-MOBIEU and P4EU and align with the principles outlined by major regulatory bodies like the WHO for biotherapeutic products [18] [2] [9]. Implementing these minimal checks provides reliable indicators of protein quality, significantly increasing confidence in published data and the ability to reproduce experimental results [2].

The Three Pillars of Minimal Protein QC

The minimal QC package assesses three fundamental characteristics of a recombinant protein sample. The following table summarizes the objective and key analytical methods for each pillar.

Table 1: Core Components of a Minimal QC Package for Recombinant Proteins

| QC Component | Objective | Key Analytical Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Identity | To confirm the protein's primary structure is correct and matches the intended construct. | - Mass Spectrometry (Intact mass or peptide mapping)- Tryptic digest with mass fingerprinting |

| Purity | To assess the proportion of the target protein relative to contaminants (e.g., host cell proteins, nucleic acids). | - SDS-PAGE/Capillary Electrophoresis- Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC) |

| Homogeneity | To evaluate the size distribution and oligomeric state, detecting aggregates or incorrect oligomers. | - Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) |

Identity

Identity verification confirms that the amino acid sequence of the purified protein matches the intended construct from the expression vector. This step is critical to ensure that the reagent being used in experiments is, in fact, the correct protein and not a contaminant or a wrongly expressed gene product [2].

- Minimal Requirement: The complete sequence of the recombinant construct must be made available, and it is highly recommended to verify this sequence after cloning [2].

- Recommended Technique: Mass Spectrometry (MS) is the gold standard. "Bottom-up" MS (mass fingerprinting of tryptic digests) confirms the protein's identity, while "top-down" MS (measuring intact protein mass) confirms identity and reveals proteolysis or other micro-heterogeneity [2].

Purity

Purity analysis determines the level of contaminants in the protein preparation. These contaminants can include host cell proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, or unwanted isoforms of the target protein, any of which can lead to experimental artifacts and non-reproducible results [2].

- Minimal Requirement: Protein purity should be assessed using widely available techniques that can separate and visualize protein species based on size or hydrophobicity [2].

- Recommended Technique: SDS-PAGE stained with Coomassie Blue or silver stain provides a quick, visual assessment of purity and can detect major contaminating proteins or protein degradation. For a more quantitative analysis, Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) or Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC) are highly effective. Mass spectrometry and RPLC can also help detect minor truncations and proteolysis [2].

Homogeneity

Homogeneity, or dispersity, refers to the size distribution and oligomeric state of the protein sample in solution. A homogeneous preparation indicates that the protein is in a stable, defined state, which is often a prerequisite for functional activity [2].

- Minimal Requirement: The sample's oligomeric state and the presence of higher-order aggregates should be evaluated. While polydispersity is not inherently an indicator of instability, the presence of incorrect oligomeric states or aggregates suggests the protein may not be in an optimal or functional state [2].

- Recommended Technique: Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) separates protein species based on their hydrodynamic radius, providing information on the oligomeric state and the presence of aggregates. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) offers a rapid assessment of the particle size distribution and polydispersity of the sample in its native buffer. For the most accurate determination, SEC coupled to multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) is the preferred method [2].

Experimental Protocols for Minimal QC

The following section provides detailed, step-by-step protocols for performing the minimal QC tests.

Protocol: Assessing Purity by SDS-PAGE

Principle: Proteins are denatured with SDS and reducing agents, then separated by molecular weight in a polyacrylamide gel under an electric field. Staining visualizes the protein bands.

Materials:

- Purified protein sample

- SDS-PAGE gel (appropriate percentage)

- SDS-PAGE running buffer

- Protein molecular weight marker

- Coomassie Blue or silver stain solution

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mix a volume of purified protein (typically 1-5 µg) with an equal volume of 2X SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Heat the sample at 95°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Gel Setup: Assemble the gel electrophoresis unit and fill the chambers with running buffer.

- Loading: Load the prepared protein sample and the molecular weight marker into separate wells of the gel.

- Electrophoresis: Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 120-150V) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel.

- Staining and Destaining:

- Coomassie Blue: Place the gel in Coomassie staining solution for at least 1 hour with gentle agitation. Transfer to destaining solution until the background is clear and protein bands are visible.

- Silver Stain: Follow a manufacturer-specific protocol for higher sensitivity.

- Analysis: Image the gel. A pure protein sample should show a single dominant band at the expected molecular weight. Additional bands indicate the presence of contaminants, proteolytic fragments, or isoforms.

Protocol: Assessing Homogeneity by Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

Principle: A liquid chromatography technique that separates proteins in their native state based on their hydrodynamic volume as they pass through a porous matrix.

Materials:

- HPLC or FPLC system

- SEC column (e.g., Superdex or similar)

- Isocratic SEC buffer (e.g., PBS or Tris-based, compatible with the protein)

- Purified protein sample (clarified and concentrated)

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Equilibrate the SEC column with at least 2 column volumes (CV) of the chosen isocratic buffer at the recommended flow rate. Ensure the system baseline is stable.

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge the protein sample at high speed (e.g., 14,000-16,000 x g) for 10 minutes to remove any insoluble particles or aggregates. The sample volume should be appropriate for the column size (typically 0.5-2% of the CV).

- Injection and Run: Inject the clarified protein sample onto the column and elute isocratically with the SEC buffer, monitoring the UV absorbance (e.g., at 280 nm).

- Data Analysis: Analyze the resulting chromatogram. A monodisperse, homogeneous sample will produce a single, symmetric peak. The presence of multiple peaks or shoulders indicates different oligomeric states or aggregates. A peak eluting at the void volume suggests high-molecular-weight aggregates.

Protocol: Confirming Identity by Intact Mass Spectrometry

Principle: The exact molecular mass of the intact protein is measured with high accuracy and compared against the theoretical mass calculated from the amino acid sequence.

Materials:

- Purified protein sample in a volatile buffer (e.g., ammonium bicarbonate, avoid non-volatile salts and detergents)

- LC-MS system with electrospray ionization (ESI) source

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Desalt the protein sample into a volatile MS-compatible buffer using a spin column or online desalting. A typical concentration of 1-10 µM is required.

- LC-MS Setup: Use a reversed-phase UPLC column coupled directly to the mass spectrometer. A short, steep gradient of acetonitrile in water with 0.1% formic acid is typically used for rapid elution and desalting.

- Data Acquisition: Inject the sample and acquire mass spectrometry data in the appropriate m/z range for the protein's expected mass. The instrument will typically generate a spectrum of multiply charged ions.

- Data Deconvolution: Use the instrument's software to deconvolute the spectrum of multiply charged ions into a zero-charge mass spectrum.

- Analysis: Compare the experimentally determined intact mass with the theoretical mass. A match within the instrument's mass accuracy confirms the protein's identity and can reveal the presence of post-translational modifications or proteolytic processing.

Visualizing the Minimal QC Workflow

The logical relationship and workflow between the minimal information requirements and the three core QC tests can be visualized as follows:

Figure 1: Minimal QC Workflow for Recombinant Proteins

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the minimal QC package requires specific reagents, tools, and equipment. The following table details key solutions used in the field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Protein QC

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Beads (e.g., Strep-TactinXT) | Rapid, efficient purification of tagged proteins; enables automation and scalability [19]. | Affinity purification step before QC analysis. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems | Bypasses living cells for protein production; allows precise control over glycosylation and PTMs [19]. | Expression of difficult-to-produce proteins for QC. |

| Advanced Detergents & Nanodiscs | Solubilizes and stabilizes membrane proteins in a native-like lipid environment [19]. | Maintaining homogeneity of membrane proteins during SEC and DLS. |

| BirA Biotin Ligase | Enables in vivo site-specific biotinylation of recombinant proteins for various assays [19]. | Labeling proteins for interaction studies post-QC. |

| National Biologics Facility (DTU) | Provides access to high-throughput protein production and characterization resources [19]. | Outsourcing large-scale protein production and QC. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | Measures particle size distribution and assesses sample homogeneity and aggregation state [2]. | Directly used in the Homogeneity assessment protocol. |

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms | Accelerates the process of identifying optimal expression and purification conditions [19]. | Streamlining the production of high-quality protein for QC. |

The implementation of a minimal QC package—systematically assessing Identity, Purity, and Homogeneity—is a fundamental practice for any researcher or professional working with recombinant proteins. By adhering to these standardized guidelines and employing the detailed protocols provided, the scientific community can significantly enhance the reliability and reproducibility of experimental data, thereby accelerating drug development and basic research.

The Minimal QC Toolkit: Practical Methods for Assessing Purity, Identity, and Homogeneity

{ article }

Assessing Protein Purity: A Comparison of SDS-PAGE, Capillary Electrophoresis, and RPLC

Application Notes and Protocols

Within the context of minimal quality control (QC) tests for recombinant protein samples, assessing protein purity is not merely a preliminary step but a fundamental requirement for ensuring reliable and reproducible research data [2]. The use of poorly characterized protein reagents has been identified as a significant contributor to the crisis of data irreproducibility in preclinical research, underscoring the need for robust, standardized analytical techniques [2] [20]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for three cornerstone methods used in purity assessment: Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), Capillary Electrophoresis (CE), and Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC). The objective is to furnish researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with clear methodologies and comparative data to select and implement the most appropriate technique for their specific QC needs, thereby enhancing the reliability of downstream experimental results.

The following table summarizes the core attributes, advantages, and limitations of SDS-PAGE, CE-SDS, and RPLC, providing a high-level comparison to guide technique selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Purity Analysis Techniques.

| Feature | SDS-PAGE | CE-SDS | RPLC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Size-based separation in a gel matrix [21] | Size-based separation in a polymer-filled capillary [22] [23] | Hydrophobicity-based separation on a column [2] [24] |

| Throughput | Medium (manual) | High (automated) [25] | High (automated) |

| Quantitation | Semi-quantitative (via staining intensity) [24] | Highly quantitative (UV detection) [23] | Highly quantitative (UV, MS detection) [2] [24] |

| Resolution | Good | Excellent [23] | Excellent |

| Sample Consumption | Moderate (µg range) | Low (ng-pg range) [22] | Low |

| Key Advantage | Simple, low equipment cost, visual result | Automated, high resolution and reproducibility, no staining [25] [23] | Direct coupling to MS for identity confirmation, high sensitivity [2] |

| Key Limitation | Labor-intensive, low quantitative precision | Limited preparative capability | Uses organic solvents, can denature proteins |

Detailed Methodologies

SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis)

3.1.1 Principle SDS-PAGE separates proteins based on their molecular weight under denaturing conditions [21]. The anionic detergent SDS binds to proteins at a nearly constant ratio (~1.4 g SDS per 1 g protein), masking the proteins' intrinsic charge and conferring a uniform negative charge density. When an electric field is applied, these SDS-protein complexes migrate through a polyacrylamide gel matrix, which acts as a molecular sieve. Smaller proteins move faster, while larger ones are retarded, resulting in separation by apparent molecular mass [21].

3.1.2 Experimental Protocol

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein sample with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (containing SDS, a reducing agent like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol to break disulfide bonds, and a tracking dye). Heat the mixture at 90-95°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [21].

- Gel Preparation: Prepare a discontinuous gel system comprising a stacking gel (pH ~6.8, low acrylamide %) and a separating gel (pH ~8.8, higher acrylamide % tailored to the protein's size range). Polymerize the gels using ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED [21]. Pre-cast gels are a convenient alternative.

- Electrophoresis: Load the denatured samples and a molecular weight marker into the gel wells. Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 150-200 V) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel.

- Staining and Visualization: After electrophoresis, proteins are fixed in the gel and then stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue or a more sensitive silver stain to visualize the bands [21].

- Analysis: Purity is assessed qualitatively by the presence of a single band at the expected molecular weight. Semi-quantitation of impurities can be achieved by densitometric analysis of the gel image.

Capillary Electrophoresis-SDS (CE-SDS)

3.2.1 Principle CE-SDS, also known as capillary gel electrophoresis (CGE), is the automated, capillary-based counterpart to SDS-PAGE [22]. Proteins are denatured with SDS and injected into a capillary filled with a replaceable sieving polymer matrix. Application of a high voltage drives the negatively charged SDS-protein complexes through the capillary. Separation by size occurs within the polymer network, and proteins are detected in real-time near the outlet of the capillary via UV absorbance (e.g., at 220 nm) [25] [23]. This method eliminates the need for staining and destaining, providing direct quantitative data.

3.2.2 Experimental Protocol (Based on AAV Capsid Protein Analysis [25])

- Sample Preparation: Mix 5 µL of protein sample (with salt concentration < 40 mM) with 5 µL of 1% SDS and 1.5 µL of 2-mercaptoethanol (for reduced conditions). Incubate at 50°C for 10 minutes. Dilute the mixture with 90 µL deionized water. For samples in high-salt buffers, a buffer exchange step is required [25].

- Instrument Setup: Use a CE system (e.g., SCIEX PA 800 Plus) equipped with a UV detector and a bare fused-silica capillary. The capillary temperature is typically maintained at 25°C, and detection is performed at 220 nm [25].

- Separation Method: The method typically includes a series of capillary rinses (with 0.1 N HCl, deionized water, 0.1 N NaOH, water, and gel buffer) followed by a water plug injection for sample stacking. The sample is injected electrokinetically (e.g., at 5 kV for 20 seconds). Separation is performed at a constant voltage (e.g., 500 V/cm) for 30-35 minutes [25].

- Data Analysis: The resulting electropherogram is analyzed using dedicated software (e.g., 32 Karat). Purity is determined by calculating the relative peak area percentages of the main product and any impurities. The method shows excellent repeatability, with RSDs for corrected peak area often below 0.7% [25].

Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC)

3.3.1 Principle RPLC separates proteins based on their hydrophobicity. The protein mixture is injected onto a chromatographic column packed with a non-polar stationary phase (e.g., C4, C8, or C18 bonded silica). Proteins are eluted using a gradient of an organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile or methanol) in water, typically with a small percentage of ion-pairing agent (e.g., trifluoroacetic acid, TFA). The TFA makes the proteins more hydrophobic and improves peak shape. More hydrophobic proteins retain longer on the column [2] [24].

3.3.2 Experimental Protocol

- Sample Preparation: Protein samples should be compatible with the initial mobile phase conditions (typically aqueous with a low percentage of organic solvent). Centrifugation or filtration is recommended to remove particulate matter.

- HPLC System and Column: A standard HPLC or UHPLC system capable of delivering precise gradients is used. Common columns include those with wide-pore (300 Å) C4 or C8 stationary phases to accommodate large protein molecules.

- Separation Method:

- Mobile Phase A: Water with 0.1% TFA (or formic acid for MS compatibility).

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA (or formic acid).

- Gradient: A linear gradient from 5% B to 95% B over 10-60 minutes, depending on the protein and required resolution.

- Flow Rate: 0.5-1.0 mL/min for analytical columns.

- Detection: UV detection at 214 nm or 280 nm is standard. For identity confirmation, the effluent can be directly coupled to a mass spectrometer (RPLC-MS) [2].

- Data Analysis: Purity is quantified by integrating the peak areas in the chromatogram. The area percent of the main peak represents the purity, while other peaks are identified as impurities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials essential for successfully implementing the protein purity assessment techniques described above.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Purity Analysis.

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, essential for both SDS-PAGE and CE-SDS [21]. |

| DTT or β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents used to break disulfide bonds, ensuring complete protein denaturation and linearization [21] [25]. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-Acrylamide | Monomer and cross-linker used to form the porous polyacrylamide gel matrix for SDS-PAGE [21]. |

| Replaceable Sieving Polymer (e.g., LPA, Dextran) | Linear polymer matrices (e.g., linear polyacrylamide) used as the separation medium in CE-SDS, allowing for high reproducibility and automated capillary rinsing [22]. |

| C4/C8/C18 RPLC Columns | HPLC columns with wide-pore silica and alkyl chain ligands (C4, C8, C18) that serve as the stationary phase for separating proteins by hydrophobicity [24]. |

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) | Ion-pairing reagent used in RPLC mobile phases to improve protein retention and chromatographic peak shape [24]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Pre-stained or unstained protein ladders of known molecular weights, used as standards in SDS-PAGE and CE-SDS for size estimation [21]. |

Workflow Integration for Minimal QC

Integrating these analytical techniques into a minimal QC workflow, as proposed by community guidelines [2], ensures a comprehensive assessment of recombinant protein quality. The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for applying these methods.

SDS-PAGE, CE-SDS, and RPLC each offer distinct advantages for protein purity analysis within a minimal QC framework. SDS-PAGE remains a valuable, accessible tool for initial, qualitative purity checks. For quantitative, high-resolution analysis required in biopharmaceutical development, CE-SDS provides superior reproducibility, resolution, and automation over traditional SDS-PAGE [23]. When identity confirmation and detection of subtle modifications are paramount, RPLC, particularly when coupled with mass spectrometry, is the technique of choice [2]. By understanding the capabilities and optimal applications of each method, researchers can construct a robust QC pipeline that significantly enhances the reliability and reproducibility of data generated with recombinant protein reagents.

{ /article }

Within the framework of minimal quality control (QC) tests for recombinant protein samples, assessing homogeneity and oligomeric state is a non-negotiable step for ensuring research data reproducibility and therapeutic efficacy [2]. These attributes directly influence a protein's biological activity, stability, and potential immunogenicity [26]. This application note details three pivotal techniques—Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), and SEC coupled with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS). We provide a comparative analysis, detailed protocols, and integrated workflows to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the most appropriate method for their specific characterization challenges.

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) separates protein molecules based on their hydrodynamic volume as they pass through a porous resin, providing a profile of the different species in a sample [26]. It is a versatile and widely used workhorse for assessing aggregation and oligomeric states.

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) measures the fluctuation in scattered light from particles undergoing Brownian motion to determine their hydrodynamic radius [26]. Its key strength is analyzing polydispersity and detecting sub-micron aggregates in a non-invasive, rapid measurement.

SEC-MALS is a powerful orthogonal technique that combines the separation capability of SEC with the absolute molar mass determination of MALS [27]. This coupling allows for the direct determination of molar mass independently of elution volume, making it the gold standard for characterizing oligomeric state and complex stoichiometries.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of SEC, DLS, and SEC-MALS

| Characteristic | SEC | DLS | SEC-MALS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Parameter | Hydrodynamic volume (separation) | Hydrodynamic radius (Rh) | Absolute Molar Mass & Hydrodynamic volume |

| Sample Throughput | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Sample Consumption | Moderate (µg-mg) | Low (µL volume) | Moderate (µg-mg) |

| Key Strength | Separation & quantification of mixtures | Speed, ease of use, & minimal sample | Absolute mass for unambiguous identification |

| Limitation | Indirect mass calibration | Low resolution in polydisperse samples | Complex instrumentation & data analysis |

Table 2: Detection Capabilities for Protein Species

| Protein Species | SEC | DLS | SEC-MALS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer | Detected & quantified | Detected as main peak | Detected, quantified & mass confirmed |

| Oligomers (Dimers, Trimers) | Resolved & quantified if size difference sufficient | Poorly resolved; contributes to polydispersity | Resolved & mass determined |

| High-Order Aggregates | Detected (exclusion volume peak) | Sensitive detection (intensity-weighted) | Detected & mass characterized |

| Low-Abundance Species | May be detected depending on load | Limited sensitivity (number-weighted) | Sensitive detection post-separation |

| Sample Purity & Homogeneity | Qualitative/quantitative via peak profile | Quantitative via Polydispersity Index (PDI) | Quantitative & mass-based identification |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

This protocol outlines the steps for analyzing a recombinant protein sample using SEC to separate and quantify monomeric and aggregated species.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

- SEC Column: Pre-packed size exclusion column (e.g., Superdex Increase series from Cytiva).

- Mobile Phase: Filtered (0.22 µm) and degassed buffer (e.g., PBS or Tris-based).

- Protein Standards: A set for column calibration (e.g., thyroglobulin, BSA, ovalbumin).

- Equipment: HPLC or FPLC system with a UV/Vis detector.

Procedure

- System Equilibration: Connect the chosen SEC column to the chromatography system. Equilibrate with at least 1.5 column volumes (CV) of mobile phase at a constant flow rate (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mL/min for analytical columns) until a stable baseline is achieved.

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge the protein sample (≥ 0.5 mg/mL) at high speed (e.g., 14,000-16,000 × g) for 10 minutes to remove any insoluble particulates. Load a defined volume (typically 10-100 µL) onto the injection loop.

- Chromatography Run: Inject the sample and run the isocratic elution with mobile phase, monitoring the UV absorbance at 280 nm.

- Data Analysis: Identify peaks in the chromatogram. The void volume contains large aggregates, followed by oligomers, the monomeric peak, and finally any low-mass fragments. Quantify the percentage of monomer and aggregates by integrating the respective peak areas.

Protocol for Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

This protocol describes how to perform a DLS measurement to determine the hydrodynamic size distribution and polydispersity of a protein sample.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

- DLS Instrument: e.g., Anton Paar Litesizer, Malvern Zetasizer.

- Ultra-Micro Cuvettes: Disposable or quartz, with low particle background.

- Sample Filters: 0.1 or 0.22 µm filters for buffer and sample clarification.

Procedure

- Buffer Preparation: Filter the buffer through a 0.1 or 0.22 µm filter into a clean container.

- Sample Preparation: Dialyze or dilute the protein sample into the filtered buffer. Centrifuge the sample at high speed (e.g., 14,000-16,000 × g) for 10 minutes immediately before loading to remove dust. A typical concentration range is 0.1-1 mg/mL.

- Measurement: Pipette the clarified sample into a clean cuvette (avoiding bubbles) and place it in the instrument. Set the measurement temperature. Perform a minimum of 3-12 sequential measurements to obtain a statistically valid result.

- Data Analysis: The instrument software will provide the Z-average diameter (the intensity-weighted mean hydrodynamic size) and the Polydispersity Index (PDI). A PDI value below 0.1 indicates a monodisperse sample, while values above 0.2-0.3 suggest a polydisperse sample with multiple species.

Protocol for SEC-MALS

This protocol integrates SEC separation with inline MALS detection for absolute molar mass determination of eluting species.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

- SEC-MALS System: An FPLC/HPLC system coupled with a MALS detector and a refractive index (RI) detector.

- Columns & Mobile Phase: As described in the SEC protocol.

- Protein Standards: Narrow-molar-mass standards for MALS system normalization (e.g., BSA monomer).

Procedure

- System Setup & Normalization: Connect the SEC column, UV, MALS, and RI detectors in series. Flush the system with filtered and degassed mobile phase. Perform a MALS detector normalization according to the manufacturer's instructions using a known protein standard.

- Sample Preparation & Injection: Prepare the sample as detailed in the SEC protocol (steps 2). Inject the sample onto the SEC column.

- Data Collection: As the sample elutes, the UV detector provides the concentration profile, the MALS detector measures the light scattering intensity at multiple angles, and the RI detector provides complementary concentration information.

- Data Analysis: Using the software, the molar mass (M) at each elution slice is calculated directly from the fundamental light scattering equation, which relates the measured light scattering intensity to the product of molar mass and concentration. This yields a mass-overlay chromatogram, confirming the absolute mass of monomers, oligomers, and aggregates without relying on calibration standards.

Integrated Workflows and Complementary Techniques

A Decision-Support Workflow for Method Selection

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for selecting the appropriate analytical technique based on sample knowledge and characterization goals.

Orthogonal Methods and the Role of Mass Photometry

Integrating orthogonal techniques is crucial for a robust characterization strategy [26] [2]. Mass Photometry has emerged as a powerful complementary tool. It measures the mass of single particles in solution without labels, providing a histogram of the mass distribution and relative abundance of species present [28]. Its key advantages include:

- Single-Particle Sensitivity: Provides high-resolution information on complex formation and detects low-abundance species that might be averaged out in bulk techniques like DLS [28] [29].

- Minimal Sample Consumption: Requires only 10-20 µL of sample at nanomolar concentrations, making it ideal for precious samples [29].

- Speed and Simplicity: Measurements take about one minute with no complex preparation, enabling rapid screening of buffer conditions or sample quality prior to more resource-intensive techniques like SEC-MALS or cryo-EM [28] [29].

A rigorous assessment of homogeneity and oligomeric state is a cornerstone of the minimal QC standard for recombinant proteins [2]. SEC, DLS, and SEC-MALS each offer unique and complementary capabilities. While DLS provides the fastest screen for sample monodispersity, SEC excels at separating and quantifying mixtures, and SEC-MALS delivers unambiguous, absolute molar mass determination. By understanding the strengths and limitations of each technique and employing them within an integrated workflow—potentially augmented by innovative tools like mass photometry—researchers can ensure the integrity of their protein reagents, thereby significantly improving the reliability and reproducibility of their scientific and therapeutic outcomes.

Comprehensive characterization of biotherapeutics is necessary to satisfy safety standards set by regulatory agencies and helps to ensure protein drug efficacy [30]. Within the framework of minimal Quality Control (QC) tests for recombinant protein samples, confirming protein identity and intactness is a fundamental requirement to guarantee the reliability and reproducibility of research data [2] [9]. The use of poor-quality proteins as experimental reagents directly impacts both the quality and cost of research [2].

Mass spectrometry (MS) has become an indispensable tool for this purpose, primarily through two complementary approaches: intact protein analysis and analysis of tryptic peptides [31] [32]. Intact protein analysis, or intact mass analysis, provides information on the accurate mass of the protein and the relative abundance of its isoforms, facilitating structural confirmation and accurate identification of protein modifications [30]. Conversely, tryptic digest-based methods (often termed "bottom-up" proteomics) involve enzymatically cleaving proteins into peptides, which are then analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to confirm identity [31] [33]. The implementation of these techniques as routine QC checks provides robust indicators of protein sample quality and yields more reproducible results in downstream applications [2].

Core Principles of Mass Spectrometry in Protein QC

The Minimal QC Framework

The minimal QC guidelines for purified proteins, as proposed by the ARBRE-MOBIEU and P4EU networks, encompass three essential tests [2]:

- Purity: Assessed by techniques like SDS-PAGE or LC-MS to detect contaminating proteins or proteolysis.

- Homogeneity/Dispersity: Assessed by techniques like DLS or SEC to evaluate oligomeric state and aggregation.

- Identity and Intactness: Confirmed using either ‘bottom-up’ MS (mass fingerprinting of tryptic digests) or ‘top-down’ MS (by measuring intact protein mass). The former confirms the correct protein is present, while the latter confirms identity and indicates whether it has suffered any proteolysis during purification [2].

The selection between intact mass analysis and peptide-based methods depends on the specific experimental goals, required information, and available resources [31].

Comparative Analysis of Intact vs. Digest Approaches

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of both methods in the context of protein QC.

Table 1: Comparison of Intact Mass Analysis and Tryptic Digest-Based Methods for Protein QC

| Parameter | Intact Mass Analysis | Tryptic Digest + LC-MS/MS |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | Accurate molecular weight of the intact protein or proteoform [30] [34]. | Amino acid sequence coverage, identification of point mutations, and precise PTM localization [31] [33]. |

| Key Strength | Detects proteoforms, monitors overall modification status, and assesses macro-heterogeneity without digestion artifacts [34]. | High sensitivity and specificity; capable of distinguishing highly similar isoforms (e.g., ApoE2, E3, E4) [31] [35]. |

| Throughput | Faster sample preparation (minimal steps) [31]. | Longer sample preparation due to digestion and processing [31]. |

| Cost & Accessibility | Can be more costly, often requiring high-resolution mass spectrometers [31]. | Lower cost, can be performed on more widely available LC-MS/MS systems like triple quadrupoles [31]. |

| Typical Mass Accuracy | ~10 ppm for modern Fourier transform MS [34]. | High confidence from sequence data and fragment ion matching. |

| Ideal Application | Lot-release consistency, quantification of glycoforms, and analysis of biotherapeutics in their native state [30]. | Definitive protein identification, detection of sequence variants, and clinical diagnostics [31]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Intact Protein Mass Analysis

This protocol is designed for the analysis of a purified recombinant protein to confirm its intact mass and is based on best practices outlined by the Consortium for Top-Down Proteomics [34].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Protein Sample: Purified recombinant protein.

- MS-Compatible Buffer: 50-200 mM ammonium acetate (pH 7.0) is recommended for native MS; for denaturing MS, a water/acetonitrile mixture with 0.1% formic acid can be used [34].

- Desalting Cartridge: e.g., Supermacroporous reversed-phase cartridge for online desalting [30].

- LC-MS System: High-resolution accurate mass (HRAM) instrument, such as an Orbitrap or Q-TOF mass spectrometer [30] [34].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation and Buffer Exchange:

- If the protein is in a non-volatile buffer (e.g., PBS, Tris, or containing salts), perform a buffer exchange into an MS-compatible buffer. This is critical as non-volatile salts cause severe signal suppression [34].

- Method: Use a centrifugal filter unit with an appropriate molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) or perform dialysis against 50-200 mM ammonium acetate. Alternatively, use online desalting cartridges [30] [34].

- Determine protein concentration using a compatible method (e.g., UV spectrophotometry).

LC-MS Analysis:

- Liquid Chromatography: Employ a reversed-phase (e.g., C4 or C8 column) or size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) system coupled online to the mass spectrometer. For native MS, use a SEC column equilibrated with ammonium acetate [30] [34].

- Mass Spectrometry:

- Ion Source: Electrospray Ionization (ESI).

- Mass Analyzer: Set the mass spectrometer to acquire data in a suitable range (e.g., m/z 500-4000 for denatured proteins, higher for native MS). Use resolving power >60,000 to ensure accurate mass determination [34].

- Key Instrument Parameters: Optimize source and desolvation temperatures, sheath and auxiliary gas flows, and ion transfer voltages to achieve good desolvation and signal-to-noise ratio without disrupting non-covalent interactions for native MS.

Data Processing and Deconvolution:

- Process the raw mass spectrum using deconvolution software (e.g., BioPharma Finder, Xtract).

- The software algorithm (e.g., Sliding Window Algorithm) transforms the complex charge state distribution of the intact protein into a zero-charge mass spectrum [30].

- The reported mass should be within 10 ppm of the theoretical mass for FT-MS instruments to confirm identity and assess intactness [34].

Protocol for Protein Identity Confirmation via Tryptic Digest

This protocol details the in-solution tryptic digestion of a purified protein for definitive identification by LC-MS/MS, a cornerstone of bottom-up proteomics [33] [36].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Protein Sample: Purified recombinant protein.