Clearance Mechanisms of Protein Aggregation in Alzheimer's Disease: Pathways, Therapeutic Targeting, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of protein aggregation clearance pathways in Alzheimer's disease, targeting researchers and drug development professionals.

Clearance Mechanisms of Protein Aggregation in Alzheimer's Disease: Pathways, Therapeutic Targeting, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of protein aggregation clearance pathways in Alzheimer's disease, targeting researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational biology of amyloid-β and tau clearance mechanisms, examines advanced methodological approaches for studying these pathways, discusses current challenges and optimization strategies in therapeutic development, and validates approaches through comparative analysis of existing and emerging therapies. The synthesis integrates current understanding from proteomic studies, cellular degradation systems, and recent clinical trial data to present a holistic view of the field and identify promising future research directions for disease-modifying treatments.

The Cellular Machinery: Understanding Fundamental Clearance Pathways in Alzheimer's Pathology

Protein aggregation is a defining pathological feature of numerous neurodegenerative diseases, with Alzheimer's disease (AD) being the most prevalent [1]. The aggregation of proteins such as amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau follows a progressive pathway from soluble monomers to insoluble fibrils and plaques [2] [3]. While historically considered inert end-products, emerging evidence underscores the heightened toxicity of soluble oligomeric species, which are now regarded as primary drivers of neurotoxicity and synaptic dysfunction [2] [1]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of the molecular mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and clearance pathways associated with Aβ and tau aggregation, with particular focus on their implications for therapeutic development in Alzheimer's disease research.

The pathological significance of protein aggregates extends beyond their structural presence to their prion-like propagation capabilities, facilitating spread across neural networks and exacerbating disease progression [1]. Understanding the spatial-temporal dynamics of these aggregates, particularly the early oligomeric forms, provides critical insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at the initial stages of the pathological cascade [2] [4].

Amyloid-β (Aβ) Aggregation Pathway

Molecular Genesis and Oligomerization

The amyloid-β pathway begins with the enzymatic processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP), a transmembrane protein widely produced by brain neurons, vascular and blood cells [4]. Sequential proteolytic cleavage of APP by β-secretase (BACE1) at the ectodomain and γ-secretase at intramembranous sites generates Aβ peptides of varying lengths, with Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 being the most prominent [4]. The Aβ1-42 variant exhibits particularly strong aggregation propensity due to its enhanced hydrophobicity [4].

In the initial phase of aggregation, Aβ monomers undergo conformational changes to form soluble, oligomeric assemblies (AβOs). These oligomers are characterized by their amorphous structures rich in exposed hydrophobic regions, rendering them highly reactive and potentially the most hazardous type of aggregate [2] [1]. The formation of fibril-free AβO solutions demonstrated that while Aβ is essential for memory loss, the fibrillar Aβ in amyloid deposits is not the primary pathogenic agent [2]. Different species of AβOs have been identified, with ongoing research investigating which specific oligomeric forms represent the major pathogenic culprits [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Amyloid-β Oligomers (AβOs)

| Property | Description | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Amorphous with exposed hydrophobic regions; β-sheet-rich | SDS-PAGE shows bands at ~4-24 kDa; conformation-specific antibodies [2] |

| Toxicity Mechanisms | Bind to synaptic receptors; induce Ca2+ overload; trigger oxidative stress | LTP inhibition in hippocampal slices; neuronal hyperactivity; synapse loss [2] |

| Cellular Localization | Extracellular and intracellular pools; association with surface membranes | Immunohistochemistry of AD brain; extracellular accumulation in CSF [2] |

| Pathological Consequences | Synaptic dysfunction, tau hyperphosphorylation, insulin resistance, inflammation | Animal models show memory impairment; rescue by AβO antibodies [2] |

Aβ Oligomer Toxicity Mechanisms

Soluble AβOs act as pathogenic gain-of-function ligands that target specific cells and synapses [2]. The binding of AβOs to neuronal surfaces triggers a cascade of pathogenic events including redistribution of critical synaptic proteins and hyperactivity in metabotropic and ionotropic glutamate receptors [2]. This leads to Ca2+ overload and instigates major facets of AD neuropathology, including tau hyperphosphorylation, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and synapse loss [2].

Over a dozen candidate toxin receptors have been proposed for AβOs, with their binding triggering a redistribution of critical synaptic proteins [2]. The clinical relevance of AβOs has been established through their accumulation in AD brain and CSF, and their presence correlates with cognitive decline [2]. The vulnerability of specific neuronal populations to AβOs may explain why early-stage AD specifically targets memory circuits [2].

Figure 1: Amyloid-β Aggregation Pathway and Toxicity Mechanisms. The pathway progresses from APP processing through increasingly structured aggregates. The soluble Aβ oligomer (AβO) is highlighted as the primary toxic species that binds to synaptic receptors, triggering downstream pathological events.

Tau Aggregation Pathway

From Physiological Function to Pathological Aggregation

Tau is a predominantly neuronal, intrinsically disordered protein that is normally bound to microtubules, where it acts to modulate neuronal and axonal stability [3]. Under physiological conditions, tau promotes microtubule assembly and stability, and facilitates axonal transport [3]. In humans, six tau isoforms are expressed in the adult brain through alternative splicing of the MAPT gene, generating isoforms with either three (3R) or four (4R) microtubule-binding repeats [5].

The pathological transformation of tau begins with post-translational modifications, particularly hyperphosphorylation, which reduces tau's affinity for microtubules and promotes its aggregation [3] [5]. In the AD brain, tau protein is two to threefold hyperphosphorylated compared to the normal adult brain [5]. This hyperphosphorylation is driven by an imbalance between kinase and phosphatase activities [3].

Tau Oligomerization and Toxicity

Dissociated tau monomers undergo conformational changes leading to the formation of soluble tau oligomers (TauO), which are now recognized as the most toxic tau species [6] [3] [5]. These oligomers are highly heterogeneous and dynamic entities that exhibit prion-like properties, enabling their propagation between cells [3] [1]. Tau oligomers cause synaptic loss in wild-type human tau transgenic mice and impair cognitive, mitochondrial, and synaptic functions [6].

The toxicity of both brain-derived tau oligomers (BDTO) and recombinant TauO (rTauO) has been well demonstrated in vivo [6]. Injecting mice with BDTO in brain areas close to or inside the hippocampus causes prompt memory impairment [6]. TauO-injected mice display impairment of cognitive, mitochondrial, and synaptic abnormalities [6]. Importantly, soluble tau oligomers are now regarded as probably the most pathologically relevant species, with evidence indicating that they inhibit neural network activity independent of fibril formation [3] [5].

Table 2: Characteristics of Pathological Tau Species

| Tau Species | Structure | Toxicity | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Tau | Intrinsically disordered; binds microtubules | Non-toxic; regulates axonal transport | Western blot, immunohistochemistry |

| Hyperphosphorylated Tau | Reduced microtubule binding; aggregation-prone | Intermediate toxicity; disrupts cytoskeleton | Phospho-specific antibodies (AT8, AT100) |

| Tau Oligomers (TauO) | β-sheet-rich; soluble; heterogeneous | Highly toxic; synaptic dysfunction; propagates between cells | T22 antibody; T18 antibody; size exclusion chromatography |

| Neurofibrillary Tangles | Insoluble fibrils; paired helical filaments | Historically considered toxic but may be protective sequestration | Thioflavin-S; Gallyas silver staining; electron microscopy |

Figure 2: Tau Protein Aggregation Pathway and Pathological Consequences. The transformation from physiological tau to hyperphosphorylated tau initiates the aggregation cascade. Tau oligomers (TauO) represent the primary toxic species responsible for multiple cellular dysfunctions.

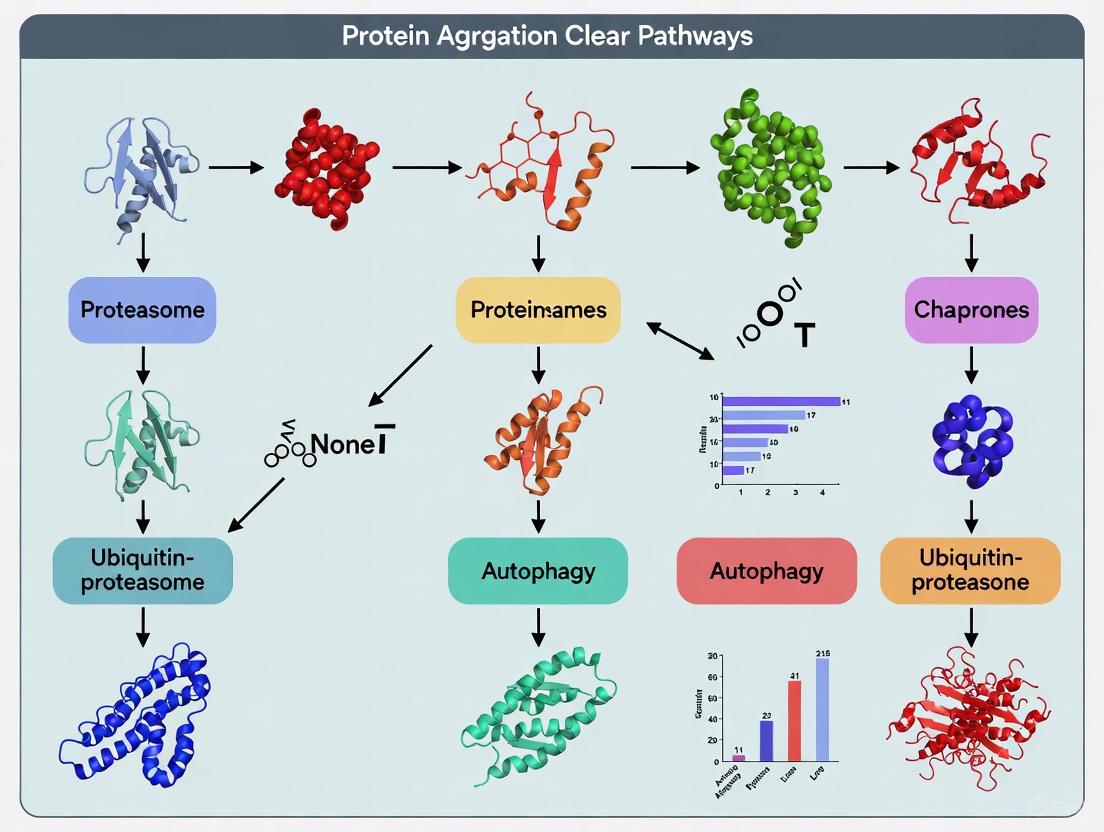

Protein Clearance Mechanisms in Alzheimer's Disease

Cellular Proteostasis Networks

The ability to maintain a functional proteome, or proteostasis, declines during the ageing process, contributing to the accumulation of damaged and misfolded proteins in neurodegenerative diseases [7]. The proteostasis network encompasses two major protein clearance systems: the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the autophagy-lysosome pathway [8] [7]. These systems work in concert to degrade unwanted, damaged, misfolded, and aggregated proteins, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis [8].

The UPS is the primary selective proteolytic system in eukaryotic cells, regulating numerous biological processes including development, signal transduction, and inflammation [8]. In this system, proteins are targeted for degradation by ubiquitination—a sequential cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligase) enzymes that attach ubiquitin molecules to substrate proteins [8]. Polyubiquitinated proteins are then recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome, a multi-catalytic protease complex [8].

Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway

The autophagy-lysosome pathway represents the second major proteolytic system, with particular relevance for the clearance of protein aggregates that cannot be degraded by the proteasome [8] [7]. Autophagy can be classified into three main types: macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) [8]. Macroautophagy involves the formation of double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes that engulf cytoplasmic cargo and deliver it to lysosomes for degradation [8] [7]. Approximately 35 autophagy-related genes (ATG) participate in this process, organizing into complexes that regulate each step of autophagy [7].

Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) is a more selective process whereby specific cytoplasmic proteins containing a KFERQ consensus motif are recognized by the chaperone Hsc70 and transported to lysosomes via the LAMP-2A receptor for degradation [8]. Both the UPS and autophagy-lysosome pathways decline during ageing, and this failure contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease [7].

Table 3: Protein Clearance Mechanisms in Neurodegeneration

| Clearance System | Components | Substrate Specificity | Role in AD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) | E1-E3 enzymes, 26S proteasome | Primarily short-lived and soluble proteins | Impaired in AD; cannot degrade oligomers/aggregates |

| Macroautophagy | ATG proteins, autophagosomes, lysosomes | Bulk cytoplasm, organelles, protein aggregates | Critical for aggregate clearance; impaired in AD |

| Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy (CMA) | Hsc70, LAMP-2A | Proteins with KFERQ motif | Declines with age; contributes to tau/Aβ accumulation |

| Microautophagy | ESCRT machinery, lysosomes | Cytosolic components directly engulfed | Role in AD not fully characterized |

Figure 3: Protein Clearance Pathways and Their Failure in Alzheimer's Disease. Cellular clearance mechanisms including the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy-lysosome pathway normally degrade protein aggregates. Age-related and pathology-related impairment of these systems leads to pathological accumulation of Aβ and tau aggregates.

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Protein Aggregation

Oligomer Preparation and Characterization

The study of protein aggregation requires sophisticated methodologies to prepare, isolate, and characterize specific aggregate species. For Aβ oligomer research, methods have been developed to generate fibril-free AβO solutions that enable the specific study of oligomer toxicity without confounding effects from fibrils or monomers [2]. These preparations typically involve very low doses of Aβ or the chaperone-like action of clusterin to stabilize oligomeric species [2].

For tau oligomer research, brain-derived tau oligomers (BDTO) can be isolated from AD brain tissue and amplified by seeding pure recombinant tau monomer (rTauM) [6]. In one established protocol, a 1:100 molar ratio of BDTO to rTauM is incubated at 37°C for 48 hours with continuous rotation to generate amplified BDTO (aBDTO) [6]. Quality control of these preparations is typically performed using immunoblotting with sequence-specific anti-tau antibodies (Tau5, Tau13) and oligomer-conformation-specific antibodies (T22, T18), alongside size exclusion chromatography [6].

Assessment of Pathological Effects

Electrophysiological approaches provide valuable tools for uncovering the mechanisms of tau oligomers on synaptic transmission within single neurons [3]. Understanding the concentration-, time-, and neuronal compartment-dependent actions of soluble tau oligomers on neuronal and synaptic properties is essential for developing effective treatment strategies [3]. New approaches are being developed that address specific challenges with current methods, allowing real-time toxicity evaluation at the single-neuron level [3].

For in vivo assessment, intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections of AβOs in animal models have been shown to impair brain insulin signaling and metabolism along with memory loss, recapitulating insulin neuropathology observed in AD brain [2]. Similarly, injecting mice with BDTO in brain areas closer to or inside the hippocampus causes prompt memory impairment, demonstrating the causal role of tau oligomers in cognitive dysfunction [6].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Aggregation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligomer-Specific Antibodies | T22 (tau oligomers), A11 (Aβ oligomers) | Detect oligomeric conformations; avoid detection of monomers/fibrils | T22 recognizes soluble tau oligomers but not tau fibrils or monomers [6] |

| Sequence-Specific Antibodies | Tau5 (total tau), Tau13 (N-terminal tau) | Detect total tau regardless of phosphorylation state | Tau5 targets epitopes 210-230; detects both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated tau [6] |

| Phospho-Tau Antibodies | AT8, AT100, PHF-1 | Detect specific phosphorylation epitopes | Critical for assessing tau hyperphosphorylation pathology |

| Amplification Reagents | Recombinant tau monomer (rTauM) | Amplify brain-derived tau oligomers for study | 1:100 molar ratio BDTO:rTauM, 37°C, 48h with rotation [6] |

| Oligomer Modulators | TMAO, sorbitol, GPC, citrulline | Modulate oligomer formation and toxicity | Brain osmolytes differentially affect aBDTO; TMAO prevents/clears aBDTO [6] |

Therapeutic Strategies and Research Directions

Targeting Oligomeric Species

Current therapeutic strategies increasingly focus on targeting the soluble oligomeric forms of Aβ and tau, as these are recognized as the most pathogenic species [2] [5]. For Aβ, promising approaches include the use of highly specific AβO antibodies that can eliminate toxins through immunotherapy [2]. Several monoclonal antibodies targeting Aβ have been developed, with aducanumab and lecanemab receiving FDA approval through accelerated pathways, though their efficacy and long-term safety remain under evaluation [5].

For tau pathology, therapeutic development has included approaches targeting tau post-translational modifications, particularly hyperphosphorylation [5]. Kinase inhibitors targeting enzymes such as GSK3β, CDK5, and p38α MAPK have been investigated to reduce tau hyperphosphorylation [5]. Additionally, tau immunotherapy using anti-tau antibodies is being explored to block the cell-to-cell propagation of tau pathology [5].

Enhancing Clearance Mechanisms

Modulation of protein clearance pathways represents another promising therapeutic avenue [8] [7]. Enhancement of proteasome activity or autophagic-lysosomal potential extends lifespan and protects organisms from symptoms associated with proteostasis disorders, suggesting that protein clearance mechanisms are directly linked to ageing and age-associated diseases [7].

Strategies to enhance autophagy include mTOR inhibition using compounds such as rapamycin and CCI-779, which induce autophagy [8]. Similarly, AMPK activation and Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) modulation can stimulate autophagic flux [7]. The interdependence of the UPS and autophagy suggests that combinatorial approaches targeting multiple clearance pathways simultaneously may yield enhanced benefits [8].

Novel Diagnostic Approaches

The clinical relevance of AβOs and tau oligomers has stimulated development of diagnostic tools targeting these species [2]. An AD-dependent accumulation of AβOs in CSF suggests their potential use as biomarkers, and new AβO probes are opening the door to brain imaging [2]. Similarly, the development of tau oligomer-specific imaging agents could enable early detection of tau pathology before the formation of neurofibrillary tangles [5].

Advanced neuroimaging techniques including PET imaging with Aβ- and tau-specific tracers allow in vivo visualization and quantification of protein aggregates in the human brain [4]. These techniques have revealed the spatial-temporal evolution of brain Aβ accumulation that occurs initially in cerebral regions with neuronal populations at high metabolic bio-energetic activity rates, spreading from neocortex to allocortex to brainstem, eventually reaching the cerebellum [4].

The understanding of protein aggregation in neurodegeneration has evolved significantly from a focus on insoluble fibrils and plaques to the recognition that soluble oligomeric species are the primary drivers of toxicity and disease progression. The intricate interplay between Aβ and tau oligomers, along with the failure of cellular clearance mechanisms, creates a self-reinforcing cycle of pathology that propagates through neural networks. Current research continues to elucidate the precise structural characteristics of these oligomers, their mechanisms of toxicity, and their spatiotemporal dynamics throughout disease progression.

Therapeutic development is increasingly targeting the early stages of the aggregation pathway, with particular emphasis on neutralizing oligomeric species and enhancing cellular clearance mechanisms. The integration of advanced diagnostic tools with targeted therapeutics holds promise for early intervention in the disease process, potentially before irreversible neuronal loss occurs. Future research directions include the development of more specific oligomer-targeting agents, combinatorial approaches addressing multiple pathological processes simultaneously, and personalized therapeutic strategies based on individual biomarker profiles.

In the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD), the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides in the brain represents a critical pathological hallmark. While genetic mutations can lead to increased Aβ production in familial AD, the majority of sporadic cases are characterized by an age-dependent impairment in Aβ clearance mechanisms [9] [4]. Enzymatic degradation constitutes a fundamental pathway for maintaining Aβ homeostasis, with neprilysin (NEP) and insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) emerging as the two most prominent Aβ-degrading enzymes [10] [11]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the enzymatic pathways responsible for Aβ clearance, focusing on their distinct mechanisms, synergistic relationships, and experimental approaches for their investigation. Understanding these pathways is essential for developing targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at enhancing Aβ clearance in Alzheimer's disease.

Core Aβ-Degrading Enzymes: Mechanisms and Specificities

Neprilysin (NEP)

Neprilysin is a membrane-bound zinc metalloendopeptidase that plays a pivotal role in extracellular Aβ degradation. As a type II membrane protein, NEP exposes its C-terminal catalytic domain to the extracellular space, positioning it ideally for interacting with Aβ peptides in the brain parenchyma [9]. Recent genetic evidence has strengthened the link between NEP and AD pathogenesis, with genome-wide association studies identifying risk variants in the MME gene encoding NEP [9].

Key characteristics of NEP include:

- Primary Localization: Cell surface and extracellular vesicles, with localization regulated by phosphorylation of its N-terminal intracellular domain [9]

- Cleavage Specificity: Preferentially cleaves Aβ at residues V12-H13, H13-H14, H14-Q15, V18-F19, F19-F20, F20-A21, K28-G29, G33-L34, L34-M35, and M35-V36 [12]

- Fragment Generation: Produces small peptide fragments consisting of 2-11 amino acid residues from monomeric Aβ40 [12]

- Substrate Range: Capable of degrading both full-length Aβ and partial structures, including Aβ16 and peptide fragments generated by other enzymes [12]

A significant functional aspect of NEP is its age-dependent decline in expression, which begins approximately after age 50 in the human temporal and frontal cortices, providing a plausible explanation for increased Aβ accumulation in sporadic AD [9]. The AD-associated M8V mutation in NEP reduces extracellular Aβ degradation not by impairing catalytic activity but by increasing phosphorylation at serine 6, which decreases NEP localization on the cell surface and extracellular vesicles [9].

Insulin-Degrading Enzyme (IDE)

IDE is a conserved Zn²⁺ metalloprotease primarily located in the cytosol, with a smaller fraction present in the extracellular space [13]. Unlike NEP, IDE exhibits a strong preference for monomeric Aβ substrates and shows limited activity against aggregated forms [12].

Key characteristics of IDE include:

- Primary Localization: Mainly cytosolic with some extracellular presence [13]

- Cleavage Specificity: Cleaves Aβ at multiple sites, generating larger fragments of 6-33 amino acid residues [12]

- Substrate Specificity: Degrades only whole Aβ40 and cannot process partial structures or fragments [12]

- Allosteric Regulation: Subject to complex regulation, with certain mutations (e.g., E111Q, cf-E111Q-IDE) exhibiting selective activity against Aβ while being inactive against insulin [13]

IDE's activity is notably affected by metal ions, particularly zinc. Zinc binding to Aβ can jeopardize IDE's catalytic activity, whereas zinc removal restores its function, suggesting potential therapeutic strategies involving zinc chelation [13].

Comparative Analysis of NEP and IDE

Table 1: Comparative characteristics of major Aβ-degrading enzymes

| Characteristic | Neprilysin (NEP) | Insulin-degrading Enzyme (IDE) | Other Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Localization | Cell surface, extracellular vesicles | Cytosol, extracellular space | Varies by enzyme |

| Cleavage Products | 23 peptides (2-11 aa) | 23 peptides (6-33 aa) | Varies by enzyme |

| Aggregated Aβ Degradation | Limited | Limited | Limited for most |

| Fragment Degradation | Can degrade Aβ fragments | Cannot degrade fragments | Varies |

| Genetic Association with AD | MME gene risk variants identified | Associated with sporadic AD | ECE-2, plasminogen system |

| Age-Dependent Decline | Significant decline after age 50 | Reduced in AD | Varies |

Table 2: Additional Aβ-degrading enzymes and their characteristics

| Enzyme | Localization | Reported Changes in AD | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endothelin-converting enzyme (ECE) | Neuronal, vascular | ECE-2 reduced in AD | Membrane-bound metalloprotease |

| Plasmin | Extracellular | Plasmin/plasminogen activators reduced in AD | Serine protease, requires activation |

| Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) | Extracellular | MMP-2, -3, -9 unchanged in AD | Can degrade both soluble Aβ and fibrils |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) | Vascular, neuronal | Increased in AD (related to plaque load) | Dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vivo Models for Studying Aβ Degradation

Genetic Mouse Models: The AppNL-F knock-in mouse model, which harbors the Swedish (KM670/671NL) and Beyreuther/Iberian (I716F) mutations in the humanized mouse App gene, recapitulates typical Aβ pathology and neuroinflammation from approximately 8 months of age [9]. This model has been crossbred with Mme knock-out (KO) and Ide KO mice to generate:

- AppNL-F × Mme KO

- AppNL-F × Ide KO

- AppNL-F × Mme/Ide double KO

These models have demonstrated that NEP deficiency accelerates Aβ plaque formation more prominently than IDE deficiency, with double knockout exhibiting a synergistic exacerbation of plaque deposition [9].

Experimental Workflow for In Vivo Assessment:

In Vivo Experimental Workflow for Assessing Aβ Pathology

In Vitro Methodologies for Studying Enzyme Activity

Aβ Degradation Assays:

- Sample Preparation: Monomeric Aβ40 is typically dissolved in appropriate buffers (e.g., PBS or Tris-HCl) and incubated with purified enzymes at specific molar ratios [12]

- Time Course Experiments: Reactions are stopped at various time points by acidification or heating to assess degradation kinetics

- Analytical Techniques:

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): Identifies specific cleavage fragments and degradation patterns [12]

- Diffusion-Ordered NMR Spectroscopy: Monitors degradation in solution state [13]

- Thioflavin T (ThT) Fluorescence: Measures aggregation kinetics in the presence of degrading enzymes [13]

- Electron Microscopy: Characterizes morphological changes in Aβ species after enzymatic treatment [13]

Cell-Based Systems: SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells have been utilized to study the functional impact of NEP mutations, particularly the AD-associated M8V variant. These systems allow assessment of extracellular Aβ degradation, enzyme localization, and the impact of post-translational modifications [9].

Comparative Degradation Mechanisms and Synergistic Relationships

Enzymatic Processing Pathways

The degradation of Aβ by NEP and IDE follows distinct mechanistic pathways with different fragment profiles. NEP generates numerous small peptides (2-11 amino acids) through cleavages primarily in the N-terminal and mid-region of Aβ, while IDE produces larger fragments (6-33 amino acids) through more limited proteolysis [12]. This differential cleavage pattern suggests complementary roles in Aβ catabolism.

Comparative Aβ Degradation Pathways by NEP and IDE

Functional Synergy Between Degradation Pathways

Recent evidence demonstrates a synergistic relationship between NEP and IDE in Aβ metabolism. While NEP deficiency has a more pronounced effect on accelerating Aβ plaque formation than IDE deficiency, the double knockout of both enzymes exacerbates plaque deposition beyond what would be expected from simply additive effects [9]. This synergy may be explained by their complementary cleavage patterns, where IDE-generated fragments can be further processed by NEP, but not vice versa [12].

The functional interaction between these enzymes extends to their response to aggregated Aβ. Neither NEP nor IDE can efficiently degrade aggregated Aβ40, highlighting the importance of targeting soluble, monomeric Aβ species for effective clearance [12]. This limitation underscores the need for therapeutic approaches that enhance enzymatic activity before significant aggregation occurs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key research reagents for studying Aβ-degrading enzymes

| Reagent/Cell Line | Key Features | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| AppNL-F Mice | Knock-in model with Swedish + Iberian mutations | In vivo assessment of Aβ pathology |

| Mme KO Mice | NEP deficiency model | Studying NEP-specific contributions to Aβ clearance |

| Ide KO Mice | IDE deficiency model | Studying IDE-specific contributions to Aβ clearance |

| SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells | Human-derived cell line | Cell-based studies of enzyme function and localization |

| cf-E111Q-IDE Mutant | Catalytically inactive against insulin | Studying allosteric regulation and Aβ-specific degradation |

| Monoclonal Aβ Antibodies | Specific to various Aβ epitopes | Detection of full-length Aβ and degradation fragments |

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite significant advances in understanding Aβ-degrading enzymes, several critical knowledge gaps remain. The precise mechanisms regulating the age-dependent decline of NEP expression are not fully elucidated. Similarly, the factors controlling IDE's transition between cytosolic and extracellular compartments require further investigation. The recent identification of AD-associated risk variants in the MME gene underscores the need to characterize the functional impact of these genetic changes on NEP activity and regulation [9].

Future research should focus on:

- Developing selective activators of NEP and IDE that enhance Aβ degradation without affecting other physiological substrates

- Exploring combination approaches that simultaneously target multiple degradation pathways

- Investigating the temporal window for therapeutic intervention, given the limited efficacy of these enzymes against aggregated Aβ

- Developing better biomarkers to monitor Aβ degradation activity in human subjects

The strategic upregulation of key Aβ-degrading enzymes represents a promising approach for preclinical AD intervention, particularly as evidence continues to support the role of impaired Aβ clearance in sporadic Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis [9].

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia, is characterized pathologically by the excessive accumulation of toxic protein aggregates in the brain—primarily amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) [14] [15]. The progressive buildup of these misfolded proteins suggests a critical failure in the brain's protein quality control mechanisms, particularly the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the autophagy-lysosomal pathway (ALP) [16] [17]. These two systems represent the major intracellular routes for maintaining proteostasis through the selective degradation of damaged organelles, misfolded proteins, and protein aggregates [18]. A growing body of genetic, pathological, and experimental evidence now confirms that impairment of both the UPS and ALP contributes significantly to AD pathogenesis [16] [14] [19]. This technical review examines the mechanisms, interactions, and therapeutic targeting of these essential clearance systems within the context of Alzheimer's disease research.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: Mechanism and Role in AD

UPS Molecular Machinery

The ubiquitin-proteasome system is the primary pathway for targeted degradation of short-lived and soluble proteins in eukaryotic cells [20]. This highly specific process occurs through two sequential steps: (1) tagging of target proteins with ubiquitin, and (2) degradation by the proteasome [16].

The tagging reaction involves a cascade of three enzymes: ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligating (E3) enzymes. Initially, a ubiquitin monomer is activated in an ATP-dependent reaction by E1. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to an E2 enzyme. Finally, an E3 ligase facilitates the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to the target protein. Repeated cycles add multiple ubiquitin molecules to form a polyubiquitin chain, with chains of four or more ubiquitins serving as the recognition signal for proteasomal degradation [16].

The proteasome complex, known as the 26S proteasome, consists of three major subunits: a 20S catalytic core and two 19S regulatory caps. The 20S core contains three distinct proteolytic activities: chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like, and peptidylglutamyl-like activities [16]. The 19S regulatory caps recognize polyubiquitinated proteins, facilitate substrate unfolding, and gate access to the catalytic channel [16].

UPS Dysfunction in Alzheimer's Pathology

Multiple lines of evidence demonstrate UPS impairment in AD brains. Histopathological studies show ubiquitin accumulations in both plaques and tangles [16]. The AD brain also contains ubiquitin-B mutant protein (UBB+1), which blocks ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis and may mediate Aβ-induced neurotoxicity [16]. Additionally, the ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), which liberates ubiquitin monomers from polyubiquitinated proteins, is oxidized and down-regulated in specific brain regions of early AD cases [16].

Mechanistic studies reveal complex interactions between AD pathology and UPS function. Keller et al. demonstrated a selective decrease in proteasome activity in AD-vulnerable brain regions like the hippocampus, while less susceptible regions like the cerebellum showed no changes [16]. In vitro evidence indicates that Aβ40 directly binds inside the proteasome and selectively inhibits its chymotrypsin-like activity [16]. Aβ42 similarly impairs proteasome function, with oligomeric species potentially exhibiting the greatest inhibitory effect [16]. Genetic studies further support UPS involvement, showing positive associations between AD and single-nucleotide polymorphisms in UBQLN1, which encodes the ubiquitin-like protein ubiquilin [16].

Table 1: Key Evidence Linking UPS Impairment to Alzheimer's Disease

| Evidence Type | Specific Findings | Research Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Histopathological | Ubiquitin accumulation in plaques and tangles; UBB+1 mutant protein in AD lesions | Immunohistochemistry, western blot |

| Biochemical | Selective decrease in proteasome activity in vulnerable brain regions; Aβ40/42 directly inhibits proteasome | Enzyme activity assays, transmission electron microscopy |

| Genetic | Association between UBQLN1 polymorphisms and AD risk | Genome-wide association studies |

| Oxidative Damage | Oxidation of UCH-L1; accumulation of oxidized proteins | Mass spectrometry, enzyme assays |

The Autophagy-Lysosomal Pathway: Mechanism and Role in AD

ALP Molecular Machinery

Autophagy is a highly conserved lysosome-dependent process for degrading intracellular long-lived proteins, protein aggregates, and organelles [14]. The ALP process involves multiple coordinated steps: initiation, phagophore formation, autophagosome maturation, fusion with lysosomes, and cargo degradation [14].

Autophagy initiation is controlled by the ULK1 complex (ULK1/2, ATG101, ATG13, and FIP200), which is regulated by nutrient-sensing pathways including AMPK and mTORC1 [14]. Nutrient deficiency inhibits mTORC1 and activates AMPK, leading to ULK1 complex activation and autophagy induction [14].

Phagophore formation requires the VPS34/PIK3C3 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex (VPS34, PIK3R4/VPS15, BECN1, ATG14L, and NRBF2), which produces phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI3P) to recruit downstream autophagy proteins [14].

Autophagosome elongation involves two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems: ATG12-ATG5-ATG16L facilitates the lipidation of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3-I to LC3-II), which becomes incorporated into the growing autophagosomal membrane [14].

Cargo degradation occurs after autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes, where contents are degraded by lysosomal hydrolases, including cathepsins B and D [18].

ALP Dysfunction in Alzheimer's Pathology

ALP impairment is increasingly recognized as a central contributor to AD pathogenesis. In normal conditions, Aβ is generated intracellularly and degraded via the autophagy-lysosomal system [18]. However, in AD, Aβ overload disrupts this pathway, creating a vicious cycle of impaired clearance and further Aβ accumulation [18]. Lysosomal dysfunction in AD involves multiple factors, including lysosomal membrane permeabilization (particularly with ApoE4), impaired acidification, and reduced cathepsin activity [18].

The relationship between autophagy and tau pathology is equally significant. Hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates, the main component of NFTs, are normally degraded through autophagy [14]. Impaired ALP function contributes to tau accumulation and spread [14] [17]. Recent evidence suggests that soluble tau oligomers, rather than mature NFTs, may be the most toxic species, and these are preferentially cleared by autophagy [14].

Table 2: Autophagy-Lysosomal Pathway Impairments in Alzheimer's Disease

| ALP Component | Nature of Dysfunction | Consequence in AD |

|---|---|---|

| Lysosomal Hydrolases | Reduced activity of cathepsins B and D; impaired acidification | Decreased degradation of Aβ and tau aggregates |

| Lysosomal Membrane | Permeabilization associated with ApoE4 | Leakage of cathepsins into cytosol; oxidative stress |

| Autophagosome Formation | Disrupted vesicle fusion; accumulation of autophagic vacuoles | Impaired clearance of protein aggregates |

| Autophagic Induction | Altered mTORC1/AMPK signaling | Reduced initiation of autophagy under stress |

Advanced Research Technologies and Experimental Approaches

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Clearance Pathways in AD

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Activity Assays | Fluorogenic substrates (Suc-LLVY-AMC for chymotrypsin-like activity) | Quantifying proteasome function in tissue extracts or live cells |

| Autophagy Modulators | Rapamycin (inductor), chloroquine (inhibitor), Bafilomycin A1 | Investigating causal relationships between autophagy and protein clearance |

| Lysosomal Function Assays | Lysotracker dyes, cathepsin activity probes, acridine orange | Assessing lysosomal pH, protease activity, and membrane integrity |

| UPS Function Assays | Ubiquitin-protein conjugates antibodies, proteasome inhibitors (MG132) | Monitoring ubiquitination status and UPS-dependent degradation |

| LRP1-Targeted Nanoparticles | Angiopep-2-conjugated polymersomes (A40-POs) | Restoring BBB transport function and enhancing Aβ clearance [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assessments

Protocol 1: Assessing Proteasome Activity in Brain Tissue

- Homogenize fresh or frozen brain tissue in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP)

- Centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C

- Collect supernatant and determine protein concentration

- Incubate aliquots with fluorogenic substrates: Suc-LLVY-AMC (chymotrypsin-like), Boc-LRR-AMC (trypsin-like), or Z-LLE-AMC (caspase-like)

- Measure fluorescence (excitation 380 nm, emission 460 nm) at 37°C over 60 minutes

- Calculate enzyme activity as fluorescence increase per mg protein per minute [16]

Protocol 2: Evaluating Autophagic Flux Using LC3 Turnover

- Culture cells expressing GFP-LC3 fusion protein or treat primary neurons with autophagy modulators

- Fix cells and immunostain for LC3 using anti-LC3 antibodies

- Quantify LC3 puncta formation per cell using confocal microscopy

- Parallel samples should be treated with lysosomal inhibitors (chloroquine 50-100 μM for 4-6 hours) to block degradation

- Calculate autophagic flux as the difference in LC3-II levels with and without inhibitors using western blot densitometry [14] [17]

Protocol 3: Assessing Aβ Clearance Across BBB Models

- Establish in vitro BBB models using primary brain endothelial cells or cell lines (bEnd.3)

- Seed cells on Transwell filters and confirm barrier integrity (TEER >150 Ω·cm²)

- Add fluorescently-labeled Aβ (e.g., Aβ1-42-Alexa488) to the apical chamber

- Apply experimental treatments (e.g., LRP1-targeted nanoparticles [21])

- Collect samples from basolateral chamber at timed intervals

- Quantify Aβ transport using fluorescence measurements or ELISA

- Confirm LRP1 involvement using receptor-blocking antibodies or siRNA approaches [21]

Signaling Pathways and Cross-Talk Between Clearance Systems

The UPS and ALP do not function in isolation but exhibit extensive cross-talk and coordination. Under normal conditions, the UPS rapidly degrades soluble misfolded proteins, while autophagy handles larger aggregates and organelles [20]. However, when one system becomes impaired, the other may compensate, though this compensatory relationship often fails in neurodegenerative conditions like AD [20].

The following diagram illustrates the key components and regulatory relationships within and between these two clearance systems:

Diagram 1: UPS and ALP Pathways in AD. The diagram shows key components of both clearance systems and their impairment by Aβ and tau pathology. Red arrows indicate inhibitory effects, while blue arrows show activation or sequential steps. Dashed lines represent cross-talk mechanisms.

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies and Research Directions

UPS-Targeted Interventions

Therapeutic strategies targeting the UPS focus primarily on enhancing proteasome activity or reducing the burden of misfolded proteins. Experimental approaches include:

Proteasome activators: Small molecules that enhance proteasome activity show promise in preclinical models but face challenges with specificity and potential off-target effects [19].

E3 ligase modulators: Compounds that regulate specific E3 ligases involved in tau or APP processing could provide more targeted approaches [19].

UPS-ALP combination therapies: Given the cross-talk between degradation systems, combined approaches may prove more effective than single-target interventions [19] [20].

ALP-Targeted Interventions

ALP-directed therapies represent a promising avenue for AD treatment, with multiple strategies in development:

mTOR-independent autophagy inducers: Compounds like metformin and other AMPK activators bypass potential side effects of direct mTOR inhibition [14] [17].

Lysosomal function enhancers: Approaches to improve lysosomal acidification or increase cathepsin activity may enhance degradation capacity without increasing autophagic flux [18].

Transcription factor EB (TFEB) activators: As a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis, TFEB represents an attractive target for comprehensively enhancing ALP function [17].

Nanotechnology and BBB-Targeted Approaches

Recent groundbreaking research demonstrates a novel nanotechnology approach that repairs blood-brain barrier function to restore Aβ clearance. Supramolecular nanoparticles designed to target low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) on the BBB act as "avidity-optimized" therapeutics that bias LRP1 trafficking toward transcytosis rather than degradation [22] [21]. This innovative strategy:

- Reduced brain Aβ by 45% within hours of administration

- Restored LRP1 expression and vascular function

- Reversed cognitive deficits in AD mouse models, with benefits lasting at least six months [22] [23] [21]

The following diagram illustrates this novel therapeutic approach and its mechanism of action:

Diagram 2: Nanoparticle-Mediated BBB Repair. This illustrates how LRP1-targeted nanoparticles restore Aβ clearance by biasing receptor trafficking toward transcytosis rather than degradation.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy-lysosomal pathway represent complementary protein quality control mechanisms whose dysfunction significantly contributes to Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. The complex interplay between these systems, along with emerging evidence of vascular clearance mechanisms, highlights the multifactorial nature of protein aggregation in AD. Current research is moving beyond simple activation or inhibition of these pathways toward more nuanced approaches that restore their natural homeostasis and coordination. The promising results from nanotechnology-based BBB repair strategies further underscore the importance of considering extracellular clearance mechanisms alongside intracellular degradation systems. As our understanding of these complex clearance networks deepens, so too does the potential for developing effective therapeutic interventions that target the fundamental protein homeostasis failures underlying Alzheimer's disease.

The efficient clearance of protein aggregates from the brain is a critical determinant in the pathogenesis and progression of Alzheimer's disease (AD). This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the principal clearance pathways, with a specific focus on interstitial fluid bulk flow driven by the glymphatic system, perivascular drainage, and receptor-mediated transport across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) via the Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1 (LRP1) and the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products (RAGE). An imbalance in the LRP1/RAGE axis significantly contributes to amyloid-β (Aβ) accumulation. Herein, we synthesize current mechanistic insights, present quantitative data from key studies, detail foundational experimental protocols, and visualize critical pathways and experimental workflows. This resource is designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge and methodologies needed to advance therapeutic strategies targeting protein clearance in neurodegenerative disorders.

The accumulation of toxic protein aggregates, such as amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau in Alzheimer's disease, results not only from overproduction but also from a failure of the brain's clearance mechanisms [24]. The brain, which lacks a conventional lymphatic system, relies on a complex set of specialized pathways to remove metabolic waste. These pathways operate within a functional unit known as the neurovascular unit (NVU), which includes vascular cells (endothelial cells, pericytes), glial cells (astrocytes, microglia), and neurons [24]. Dysfunction of the NVU is an early event in AD, leading to impaired BBB integrity and reduced cerebral blood flow, which in turn hampers the clearance of neurotoxic proteins [24].

The major clearance routes can be categorized as follows:

- The Glymphatic System and Perivascular Drainage: A paravascular network where subarachnoid cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) influx along arterial walls mixes with interstitial fluid (ISF) and solutes, facilitating their clearance along venous pathways.

- Receptor-Mediated Transport at the BBB: A highly regulated exchange of molecules between the blood and the brain, governed by specific influx and efflux receptors on endothelial cells. The LRP1 (efflux) and RAGE (influx) receptors play a particularly pivotal role in Aβ homeostasis.

Understanding the intricate balance and regulation of these pathways is fundamental to developing effective interventions for Alzheimer's disease and other proteinopathies.

Core Transport Mechanisms and Pathway Dysregulation in AD

Interstitial Fluid Bulk Flow and the Glymphatic System

The glymphatic system is a brain-wide clearance pathway that facilitates the efficient removal of solutes and waste, including Aβ. Its function is characterized by a defined directional flow [25]:

- Influx: Subarachnoid CSF enters the brain parenchyma along paravascular spaces surrounding penetrating arteries.

- Exchange: CSF mixes with ISF and solutes in the brain interstitium.

- Efflux: The combined fluid, now containing waste products, is cleared along paravenous drainage pathways.

A critical molecular component of this system is the water channel aquaporin-4 (AQP4), which is densely expressed on astrocytic endfeet ensheathing cerebral vessels. AQP4 supports the bulk fluid flow between influx and efflux routes. Studies in mice lacking AQP4 have demonstrated a ~70% reduction in interstitial solute clearance, underscoring its vital role [25].

Table 1: Experimental Tracer Data in Glymphatic Pathway Studies

| Tracer Molecule | Molecular Weight (Da) | Observation after Intracisternal Injection | Implication for Pathway Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 594 (A594) | 759 | Rapid, widespread movement throughout brain interstitium; minimal concentration in paravascular spaces [25]. | Demonstrates efficient parenchymal exchange and bulk flow of small solutes. |

| Texas Red-dextran-3 (TR-d3) | 3,000 | Concentrated in paravascular spaces but also entered the interstitium [25]. | Highlights the sieving function of astrocytic endfeet; intermediate-sized solutes can access the interstitium. |

| FITC-dextran-2000 | 2,000,000 | Confined to paravascular spaces; did not enter the surrounding interstitial space [25]. | Illustrates the size-dependent exclusion from the parenchyma; very large molecules are restricted to the paravascular influx route. |

| FITC-dextran-70 | 70,000 | Used to label and quantify perivascular spaces (PVS); more readily observed around arteries than veins [26]. | Provides a tool for visualizing the anatomical substrate of the glymphatic system and its asymmetry between arterial and venous sides. |

Perivascular Drainage and Intramural Clearance

An alternative or complementary model to the glymphatic system is the Intramural Peri-Arterial Drainage (IPAD) pathway. This model proposes that solutes, including Aβ, are cleared from the brain along the basement membranes within the walls of cerebral arteries [26]. The driving forces for this clearance are believed to include arterial pulsatility. Recent in vivo studies in mice have shown that the perivascular spaces around arteries are significantly larger and more frequently labeled by CSF tracers than those around veins, suggesting a preferential role for arteries in the influx and drainage of fluids [26]. The exact anatomical location of the drainage route—whether within the arterial wall (intramural) or directly adjacent to it (extramural)—remains a subject of ongoing investigation, but both views acknowledge the primacy of arterial pathways in solute clearance [26].

Receptor-Mediated BBB Transport: The LRP1/RAGE Axis

The BBB is a highly selective barrier formed by endothelial cells connected by tight junctions, pericytes, astrocytes, and a basement membrane [27] [28] [29]. It tightly controls molecular exchange between blood and brain via several mechanisms, with receptor-mediated transcytosis being critical for larger molecules like Aβ.

Table 2: Key Receptors in Amyloid-β Transport at the Blood-Brain Barrier

| Receptor | Primary Direction of Transport | Role in Aβ Metabolism | Expression Change in AD |

|---|---|---|---|

| LRP1(Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1) | Brain-to-Blood (Efflux) [24] | Binds to and mediates the cellular clearance of Aβ from the brain across the BBB into the circulation [30] [24]. | Decreased expression in endothelial cells, reducing Aβ clearance and contributing to accumulation [24]. |

| RAGE(Receptor for Advanced Glycation End products) | Blood-to-Brain (Influx) [24] | Binds circulating Aβ and facilitates its transport across the BBB into the brain, also mediating Aβ-induced oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [24]. | Increased expression in endothelial cells, leading to greater influx of Aβ into the brain [24]. |

| P-gp(P-glycoprotein) | Brain-to-Blood (Efflux) [24] | An ATP-dependent efflux pump that works alongside LRP1 to remove Aβ and other toxins from the brain [24]. | Deficient expression, contributing to reduced Aβ clearance [24]. |

The opposing actions of LRP1 and RAGE create a critical equilibrium at the BBB. In the healthy brain, this system maintains low levels of Aβ. In AD, the system becomes dysregulated, with decreased LRP1 and increased RAGE expression, creating a vicious cycle of Aβ accumulation and neuroinflammation [24]. LRP1's role is complex and extends beyond Aβ clearance; it also interacts with apoE, the strongest genetic risk factor for AD, and is involved in maintaining overall brain homeostasis [30]. It is important to note that LRP1's function may be disease-specific, as its deletion has been reported to be protective in Parkinson's disease models by reducing the transmission of α-synuclein [31].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Models

Key Quantitative Findings

- Glymphatic Flow Rate: Approximately 40% of intracisternally injected [³H]mannitol (182 Da) tracer was recovered in the brain within 45 minutes, demonstrating substantial CSF influx, while the larger [³H]dextran-10 (10 kDa) accumulated more slowly [25].

- AQP4 Dependence: Genetic deletion of Aqp4 in mice results in a ~70% reduction in the clearance of interstitial solutes, including soluble Aβ [25].

- Perivascular Space Dimensions: In vivo imaging in mice reveals that the perivascular spaces (PVS) around pial arteries are significantly larger than those around pial veins. The size of the PVS correlates with blood vessel diameter for pial vessels but not for penetrating vessels [26].

- LRP1 Genetic Association: A meta-analysis of 18 case-control studies (4,668 AD patients and 4,473 controls) found no overall significant effect of the LRP1 C766T polymorphism on AD risk. However, subsequent studies suggest its effect may be modified by other factors, such as tau pathology, or be associated with specific Aβ deposition patterns like cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) [30].

In Vivo and In Vitro BBB Transport Models

Understanding the permeability of the BBB is crucial for drug development. Several experimental models are used to study this.

Table 3: Experimental Models for Studying BBB Transport

| Model Type | Description | Key Applications & Measurable Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Permeability Studies | Direct injection of tracers or drugs into the bloodstream or CSF of live animals (e.g., mice), followed by measurement of brain uptake [25] [29]. | - CSF Influx: Intracisternal injection of fluorescent or radiolabeled tracers to track paravascular flow [25].- Blood-to-Brain Permeability: Intravenous injection with subsequent analysis of brain homogenates to calculate permeability coefficients (e.g., Permeability-Surface Area product) [29]. |

| In Vitro Cell-Based Models | Culture of brain endothelial cells on permeable transwell filters, often in co-culture with astrocytes or pericytes to improve barrier properties [29]. | - Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER): Measures the tightness of the cell monolayer [29].- Permeability Coefficient (Papp): Quantifies the rate of solute flux across the cell layer [29]. |

| Mathematical Transport Models | Computational models that simulate the diffusion and transport of molecules across the BBB based on physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, lipophilicity) and anatomical parameters [29]. | - Predicting Drug Permeability: In silico screening of compound libraries for BBB penetration potential [32]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Vivo Tracer Imaging of Paravascular CSF Influx

This protocol, adapted from Iliff et al. [25], details the procedure for real-time visualization of CSF tracer movement in the mouse brain.

Key Research Reagents:

- Anesthetics: Ketamine and Dexmedetomidine for induction and maintenance.

- Fluorescent Tracers: FITC-dextran (40-2000 kDa, for CSF) and Texas Red-dextran-70 (70 kDa, for blood plasma).

- Artificial CSF (aCSF): Ionic solution mimicking natural CSF.

- Surgical Equipment: Stereotactic frame, dental drill, glass cover slip.

Procedure:

- Animal Preparation and Cranial Window: Anesthetize a mouse and secure it in a stereotactic frame. Perform a craniotomy by carefully drilling and removing a ~3 mm diameter circle of skull above the region of interest (e.g., the middle cerebral artery), leaving the dura intact. Seal the opening with a glass coverslip [25] [26].

- Tracer Injection: Inject FITC-labeled dextran (in aCSF) into the cisterna magna at a slow, controlled rate (e.g., 1 µl/min) to label the CSF. Simultaneously or subsequently, inject Texas Red-dextran-70 intravenously (e.g., via retro-orbital injection) to label the blood plasma and visualize the vasculature [25] [26].

- In Vivo Two-Photon Imaging: Place the animal under a two-photon microscope. Using a water-immersion objective, image the cortical surface and parenchyma to depths of ~200 µm. Use appropriate excitation wavelengths (e.g., 790 nm for FITC, 910 nm for Texas Red) to track the movement of the CSF tracer in real-time.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the time-lapse image stacks to determine the kinetics of para-arterial CSF influx, the distribution of tracer between paravascular spaces and the interstitium, and the size of perivascular spaces relative to the accompanying vessel [25] [26].

Protocol: Assessing BBB Permeability to Amyloid-β

This protocol outlines methods to evaluate the functional role of LRP1 and RAGE in Aβ transport across the BBB.

Key Research Reagents:

- Radiolabeled or Fluorescently-Tagged Aβ peptides: (e.g., ¹²⁵I-Aβ40, FITC-Aβ42).

- Receptor-Specific Modulators: RAGE inhibitors (e.g., FPS-ZM1), LRP1 antagonists (e.g., RAP - Receptor-Associated Protein).

- Transwell Assay Systems: Permeable supports for in vitro BBB models.

- Antibodies: For immunohistochemistry or Western blot analysis of LRP1, RAGE, and tight junction proteins (e.g., occludin, claudin-5).

Procedure: In Vitro Transwell Assay:

- Culture a monolayer of brain endothelial cells (e.g., bEnd.3 cells or primary human BMVECs) on a transwell insert until a high TEER value is achieved.

- Apply the tagged Aβ peptide to the "luminal" (top) or "abluminal" (bottom) chamber in the presence or absence of receptor modulators.

- At timed intervals, sample from the opposite chamber and quantify the tracer that has crossed the cell layer using a gamma counter (for radioactive tracers) or a fluorometer.

- Compare transport rates between treatment groups to infer the contribution of LRP1 (efflux) or RAGE (influx) to Aβ translocation [24] [29].

In Vivo Brain Efflux Index (BEI):

- Anesthetize a rat or mouse and place it in a stereotactic frame.

- Inject a small volume of a solution containing the tagged Aβ peptide (and a reference compound) directly into a specific brain region (e.g., hippocampus or cortex).

- At designated time points, collect blood from the superior sagittal sinus and/or decapitate the animal to collect the brain.

- Measure the amount of tracer remaining in the brain and the amount that has appeared in the blood. The percentage of Aβ cleared from the brain over time provides a measure of efflux capacity, which can be compared between wild-type and genetically modified animals or after pharmacological blockade of LRP1 [29].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

The Glymphatic Pathway and LRP1/RAGE Axis in Alzheimer's Disease

Experimental Workflow for Investigating Perivascular Drainage

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Models for Investigating Brain Clearance Pathways

| Reagent / Model | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Dextrans | FITC-, TRITC-, or Alexa Fluor-conjugated; 3 kDa - 2,000 kDa [25] [26]. | Size-dependent tracers for visualizing paravascular CSF influx, interstitial diffusion, and defining the functional limits of the glymphatic system. |

| AQP4 Knockout Mice | Genetically modified mouse model lacking aquaporin-4 water channels [25]. | To definitively establish the role of AQP4 in glymphatic fluid flow and solute clearance, and to study its contribution to Aβ pathology. |

| LRP1 Modulators | Receptor-Associated Protein (RAP) - a universal LRP1 antagonist [30]. | To pharmacologically inhibit LRP1 function in vitro or in vivo, allowing researchers to dissect its specific role in Aβ efflux transport. |

| RAGE Inhibitors | Small-molecule antagonists like FPS-ZM1. | To block RAGE-mediated Aβ influx and neuroinflammatory signaling, assessing its therapeutic potential and validating its role in AD pathogenesis. |

| In Vitro BBB Models | Transwell cultures of brain endothelial cells (primary or immortalized), often co-cultured with astrocytes [29]. | To perform controlled, reductionist studies of transporter function (LRP1/RAGE), tight junction integrity, and compound permeability without the complexity of a whole organism. |

| Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) | Used in clinical and preclinical research with Gadolinium-based contrast agents [24]. | A non-invasive method to quantify BBB leakage and permeability in living subjects, allowing for longitudinal studies of NVU dysfunction in disease progression. |

The brain employs a multi-faceted clearance system, encompassing the glymphatic flow, perivascular drainage, and receptor-mediated BBB transport, to prevent the accumulation of proteotoxic waste. The dysregulation of these pathways, particularly the opposing LRP1 and RAGE functions at the BBB, is a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease pathology. A deep and quantitative understanding of these mechanisms—their kinetics, regulatory factors, and interactions—is paramount. The experimental methodologies and reagents detailed in this whitepaper provide a foundation for ongoing research. Future therapeutic success will likely depend on integrated strategies that co-target multiple clearance pathways to restore the brain's innate ability to remove protein aggregates and maintain homeostasis.

The progressive accumulation of protein aggregates is a defining pathological feature of Alzheimer's disease (AD). Glial cells, particularly microglia and astrocytes, serve as crucial regulators of brain proteostasis through specialized clearance mechanisms. This whitepaper examines the sophisticated phagocytic and degradative pathways employed by these cells to manage amyloid-β (Aβ) and other pathological proteins. We synthesize current understanding of how microglial phagocytosis and astrocytic clearance mechanisms become dysregulated during AD progression, creating a permissive environment for protein aggregation. The document further explores emerging therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating glial functions to restore proteostatic balance, with particular emphasis on targets currently under investigation for drug development. By integrating recent genetic, molecular, and clinical findings, this review provides a comprehensive technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals working to translate glial biology into effective neurodegenerative disease therapeutics.

Alzheimer's disease pathophysiology is characterized by the accumulation of misfolded proteins, primarily amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau, which aggregate into oligomers, fibrils, and ultimately mature plaques and tangles [1]. The brain maintains a delicate balance between protein production and clearance, with glial cells playing an indispensable role in this proteostatic regulation [33] [34]. When these clearance mechanisms become impaired—whether through aging, genetic risk factors, or chronic inflammatory responses—the resulting protein accumulation initiates a destructive cascade that includes synaptic dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and ultimately neuronal loss [35] [4].

Microglia and astrocytes employ complementary strategies for protein clearance. As the resident immune cells of the central nervous system (CNS), microglia function as professional phagocytes, capable of engulfing Aβ plaques, cellular debris, and synapses [36]. Astrocytes contribute to proteostasis through both enzymatic degradation and facilitator roles in Aβ transport across the blood-brain barrier [33] [34]. The coordinated efforts of these glial populations normally prevent protein accumulation; however, in AD, both cell types undergo functional alterations that transform them from protective to potentially pathogenic entities [36] [37]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing glial clearance pathways provides critical insights for developing targeted therapies aimed at restoring proteostatic balance in the AD brain.

Microglial Phagocytosis in Alzheimer's Disease

Phagocytic Mechanisms and Receptor-Mediated Clearance

Microglia constantly survey the CNS microenvironment, recognizing and phagocytosing misfolded proteins, cellular debris, and apoptotic cells through an array of specialized receptors [36]. The phagocytosis process occurs in three distinct phases: (1) the "find-me" phase involving chemotaxis toward apoptotic or damaged cells; (2) the "eat-me" phase comprising recognition and engulfment of targets; and (3) the "digest-me" phase involving enzymatic degradation of engulfed content within phagolysosomes [36].

Table 1: Key Microglial Phagocytosis Receptors in Alzheimer's Disease

| Receptor | Primary Ligand(s) | Biological Function | Role in AD |

|---|---|---|---|

| TREM2 | Apolipoproteins, Aβ | Chemotaxis, cell survival, phagocytic activation | Reduced function increases AD risk; role in Aβ compaction |

| LRP1 | Aβ, apolipoproteins | Aβ uptake and degradation | Clearance of Aβ aggregates |

| CD33 | Sialic acid residues | Inhibitory receptor dampening phagocytosis | Increased AD risk; reduces Aβ uptake |

| TAM Receptors (Tyro3, Axl, Mer) | Gas6, Protein S | Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells, Aβ plaque detection | Aβ plaque clearance; efferocytosis |

| P2Y6 | UDP | Phagocytosis of apoptotic neurons | Mediates microglial chemotaxis toward damage |

| Complement Receptors (CR3, CR4) | C3b, iC3b | Phagocytosis of opsonized targets | Excessive synaptic pruning in AD |

| Scavenger Receptors (e.g., SR-A, CD36) | Aβ fibrils, oxidized lipids | Aβ binding and uptake | Clearance of fibrillar Aβ |

During the "find-me" phase, nucleotides such as UDP and ATP released by damaged neurons act as potent chemoattractants by activating microglial P2Y6 receptors [36]. TREM2 (Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2) plays an essential role in microglial chemotaxis toward neuronal injury and non-inflammatory clearance of apoptotic neurons [36]. In the subsequent "eat-me" phase, surface-exposed phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cells is recognized by receptors including TREM2, complement receptors, and TAM family receptors (Tyro3, Axl, Mer), initiating engulfment [36] [37]. The "digest-me" phase culminates in the lysosomal degradation of internalized cargo, with cathepsin B playing a significant role in processing longer forms of Aβ into less toxic species [33].

Genetic Regulation of Phagocytic Function

Genome-wide association studies have revealed that many genes associated with increased AD risk are predominantly expressed in microglia and regulate phagocytic function [35]. These include TREM2, CD33, CR1, ABCA1, and INPP5D, among others [35]. The identification of these genetic risk factors provides compelling evidence for the central role of microglial phagocytosis in AD pathogenesis.

The TREM2 pathway is particularly crucial, as rare variants significantly increase AD risk [35] [36]. TREM2 supports microglial survival, activation, and phagocytic capacity, with its ligands including apolipoproteins and Aβ itself [36]. Upon ligand binding, TREM2 associates with the adaptor protein DAP12 to initiate downstream signaling through SYK kinase, which promotes cytoskeletal reorganization necessary for phagocytosis and activates transcriptional programs that enhance degradative capacity [35]. CD33 represents another critical immunomodulatory receptor, acting as an inhibitory checkpoint that dampens Aβ phagocytosis when engaged by sialic acid-containing glycans [35]. The balanced signaling between activating receptors like TREM2 and inhibitory receptors like CD33 fine-tunes microglial phagocytic activity in the AD brain.

Dual Roles in Neuroprotection and Neurotoxicity

Microglial phagocytosis serves paradoxically both protective and detrimental functions in AD, largely dependent on the disease stage and specific cellular targets [35]. During early disease phases, microglial phagocytosis of Aβ via TREM2, LRP1, and TAM receptors helps restrict plaque expansion and compact existing plaques, thereby limiting subsequent tau pathology [35]. This protective phagocytosis creates a physical barrier that sequesters toxic Aβ species and reduces neuritic damage.

However, in later disease stages, microglial phagocytosis becomes detrimental through excessive engulfment of synaptic structures and potentially even live neurons [35] [37]. Complement proteins C1q and C3 are deposited on synapses, marking them for elimination by microglial complement receptors [37]. This complement-mediated synaptic pruning, while essential during development, becomes pathological in the AD brain, contributing significantly to synaptic loss and cognitive decline [35] [37]. Additional receptors including P2Y6 and TREM2 itself may also mediate this excessive phagocytosis of synapses and neurons, highlighting the complex duality of these pathways [35].

Astrocytic Clearance Mechanisms

Enzymatic Degradation Pathways

Astrocytes contribute significantly to Aβ clearance through the production and secretion of a diverse array of proteolytic enzymes that degrade Aβ in the extracellular space [33] [34]. These enzymes target different cleavage sites within the Aβ sequence, generating fragments with reduced aggregation propensity and neurotoxicity.

Table 2: Major Astrocytic Aβ-Degrading Enzymes in Alzheimer's Disease

| Enzyme Class | Specific Enzymes | Aβ Species Targeted | Cellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metalloendopeptidases | Neprilysin (NEP), Insulin Degrading Enzyme (IDE), Endothelin-Converting Enzyme (ECE) | Monomeric Aβ (NEP also cleaves oligomers) | Extracellular space, cell membrane |

| Matrix Metalloproteinases | MMP-2, MMP-9 | Monomeric and fibrillar Aβ | Extracellular space |

| Lysosomal Peptidases | Cathepsin B (CAT-B) | Phagocytosed Aβ, longer Aβ forms | Intracellular lysosomes |

| Plasminogen Activators | Tissue Plasminogen Activator (tPA) | Aggregated Aβ | Extracellular space |

| Other Proteases | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) | Aggregated Aβ | Extracellular space |

Neprilysin (NEP) and insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) represent the most extensively characterized Aβ-degrading proteases [33] [34]. Both enzymes are metalloendopeptidases that cleave monomeric Aβ species, with NEP also demonstrating activity against oligomeric forms [33]. The significance of these enzymes is substantiated by animal models where genetic deletion of NEP or IDE exacerbates Aβ deposition, while their overexpression reduces Aβ burden [33]. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), particularly MMP-2 and MMP-9 secreted by astrocytes, contribute to the extracellular degradation of both monomeric and fibrillar Aβ forms [33]. Astrocyte-conditioned medium demonstrates Aβ-degrading activity that is significantly attenuated by MMP inhibitors or when derived from MMP-deficient mice [33].

Receptor-Mediated Clearance and Chaperone Functions

Beyond enzymatic degradation, astrocytes actively participate in Aβ clearance through receptor-mediated endocytosis and transporter-facilitated removal from the CNS [33] [34]. Astrocytes express several receptors capable of binding Aβ, including lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), scavenger receptors, receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), and formyl peptide receptors [34]. Following internalization, Aβ is trafficked to lysosomes where cathepsin B and other hydrolases complete its degradation [33].

Astrocytes also release extracellular chaperones that sequester Aβ and facilitate its transport across the blood-brain barrier [33] [34]. Key chaperones include apolipoprotein E (ApoE), apolipoprotein J (clusterin), α2-macroglobulin, and α1-antichymotrypsin [33]. These chaperones form complexes with Aβ that interact with transporters such as LRP1 on the abluminal side of cerebral endothelial cells, enabling Aβ efflux from the brain to the peripheral circulation [33]. The ApoE isoform (ApoE4) associated with highest AD risk demonstrates impaired Aβ binding and clearance compared to ApoE2 and ApoE3, providing a mechanistic link between this genetic risk factor and Aβ accumulation [33].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vivo and In Vitro Assessment of Phagocytosis

The investigation of glial phagocytic function employs a diverse methodological toolkit spanning in vivo imaging, ex vivo histological analysis, and in vitro assays. Two-photon intravital microscopy enables real-time observation of microglial dynamics and phagocytic activity in living animals [36]. This approach has revealed that even "resting" microglia continuously extend and retract processes to survey their microenvironment, making frequent contacts with synapses [36].

For quantitative assessment of phagocytic capacity, primary microglial and astrocytic cultures exposed to fluorescently-labeled Aβ, synaptosomes, or apoptotic cells provide a controlled system for measuring engulfment [36]. Internalization is typically quantified by flow cytometry or confocal microscopy following careful removal of surface-bound (non-internalized) targets using trypsinization or acid washes [36]. To determine the fate of ingested cargo, pH-sensitive fluorophores (e.g., pHrodo) can distinguish internalized materials within acidic phagolysosomes from those merely attached to the cell surface [37].

Table 3: Key Experimental Approaches for Studying Glial Phagocytosis

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Readouts | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Imaging | Two-photon microscopy, PET imaging | Microglial dynamics, plaque clearance, synaptic engulfment | Real-time assessment in physiological context |

| Ex Vivo Analysis Immunohistochemistry, RNA sequencing | Receptor localization, transcriptomic profiles, plaque load | Preserved tissue architecture but static snapshot | |

| In Vitro Phagocytosis Assays | Flow cytometry, confocal microscopy with pH-sensitive dyes | Quantification of internalized targets, degradation kinetics | Controlled environment but lacks full physiological complexity |

| Genetic Manipulation | CRISPR/Cas9, siRNA, transgenic models | Functional validation of specific genes | Establishes causality but may require compensatory mechanisms |

| Human Tissue Models | iPSC-derived microglia/astrocytes, cerebral organoids | Human-specific pathways, patient-specific effects | Relevance to human disease but variable differentiation efficiency |

Genetic approaches including CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing, siRNA knockdown, and analysis of transgenic models enable functional validation of specific phagocytosis receptors and signaling components [35] [36]. The emergence of human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived microglia and astrocytes provides platforms for investigating human-specific phagocytic pathways and patient-specific effects [35]. These human cell models can be exposed to brain substrates including Aβ plaques or tau fibrils to examine transcriptional and functional responses under controlled conditions [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Glial Phagocytosis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phagocytosis Reporters | pHrodo-labeled Aβ, fluorescent synaptosomes, apoptotic cells | Quantifying internalization and degradation | pH-sensitive fluorophores signal only upon phagolysosomal acidification |

| Receptor Agonists/Antagonists | TREM2 agonists, CD33 blocking antibodies, P2Y6 receptor ligands | Modulating specific phagocytic pathways | Determine receptor necessity and sufficiency |

| Genomic Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 for phagocytosis genes, scRNA-seq, RNAi | Identifying and validating genetic regulators | Single-cell sequencing reveals cellular heterogeneity |

| Cell Type-Specific Markers | IBA1 (microglia), GFAP (astrocytes), C1q (complement) | Identifying and quantifying glial populations | Multiple markers recommended for accurate identification |

| Animal Models | 5XFAD, APP/PS1, Trem2 KO, Cd33 KO | In vivo functional studies | Models vary in pathology progression and completeness of phenotypic replication |

Critical reagents for phagocytosis research include fluorescent probes that distinguish internalized targets, with pHrodo-labeled Aβ and synaptosomes being particularly valuable as their fluorescence intensifies upon phagolysosomal acidification [36] [37]. Receptor-specific agonists and antagonists allow pharmacological dissection of individual pathways, exemplified by TREM2 agonistic antibodies, CD33 blocking antibodies, and P2Y6 receptor ligands like UDP [35] [36]. Genomic tools including CRISPR/Cas9 systems optimized for primary glia enable targeted manipulation of phagocytosis-related genes, while single-cell RNA sequencing reveals transcriptomic signatures associated with different phagocytic states [35] [36]. Animal models ranging from conventional transgenics (e.g., 5XFAD, APP/PS1) to knockout strains (e.g., Trem2 KO, Cd33 KO) provide in vivo systems for evaluating phagocytic function throughout disease progression [35].

Visualization of Key Phagocytosis Signaling Pathways