Chaperone-Assisted Protein Refolding: Protocols, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to chaperone-assisted protein refolding, bridging foundational principles with practical laboratory applications.

Chaperone-Assisted Protein Refolding: Protocols, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to chaperone-assisted protein refolding, bridging foundational principles with practical laboratory applications. It explores the fundamental mechanisms by which molecular chaperones, including Trigger Factor, Spy, and the GroEL/ES system, facilitate protein folding in vitro and in vivo. Detailed, actionable protocols for refolding model proteins like carbonic anhydrase B and slow-folding GFP are presented, alongside strategies for troubleshooting common aggregation issues. The content also covers advanced validation techniques such as Hydrogen–Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) and the READ method for visualizing dynamic chaperone-substrate complexes. Finally, the article examines the critical translational role of chaperones in drug development and the targeting of protein misfolding diseases, making it an essential resource for researchers and scientists in biotechnology and biomedicine.

The Cellular Machinery of Folding: Understanding Chaperone Mechanisms

Protein folding, the process by which a linear amino acid chain attains its functional three-dimensional structure, represents one of the most fundamental challenges in molecular biology. The paradox posed by Cyrus Levinthal in 1969 highlighted the apparent impossibility of proteins exhaustively searching all possible conformations to find their native state within biologically relevant timescales [1] [2]. This Application Note examines the complementary mechanisms of spontaneous and chaperone-assisted protein folding, with particular emphasis on their roles in resolving Levinthal's paradox and their implications for experimental research and therapeutic development.

The "thermodynamic hypothesis," established by Anfinsen's pioneering experiments, demonstrated that the native structure of a protein is determined solely by its amino acid sequence and represents the most thermodynamically stable conformation under physiological conditions [3] [1]. However, the crowded intracellular environment presents additional challenges not present in vitro folding experiments, including the constant risk of aggregation and misfolding due to inappropriate interactions with other cellular components [4] [3].

Theoretical Framework: Solving Levinthal's Paradox

Energy Landscape Theory and Folding Funnels

Levinthal's paradox originates from the astronomical number of possible conformations available to a polypeptide chain. For a typical 100-residue protein, with each residue having at least three possible conformations, the chain could adopt up to 3¹⁰⁰ (~10⁴⁸) different structures. If the protein sampled conformations at picosecond rates, exhaustive search would require longer than the age of the universe, yet most small proteins fold spontaneously on millisecond to microsecond timescales [1] [2].

The resolution to this paradox lies in the concept of funnel-shaped energy landscapes, where proteins do not randomly sample all possible conformations but rather follow biased pathways toward the native state [1] [2]. In this framework, the folding process is guided by a gradual decrease in energy and conformational entropy as the protein approaches its native structure, effectively creating a "funnel" that directs the search process [1].

Table 1: Key Theoretical Concepts Resolving Levinthal's Paradox

| Concept | Explanation | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Funnel-shaped Energy Landscape | Rugged landscape with overall bias toward native state | Φ-value analysis, folding kinetics studies [1] |

| Nucleation-Condensation | Small native-like region serves as folding nucleus | Protein engineering experiments [3] |

| Foldon Assembly | Modular folding of independent structural units | Hydrogen-deuterium exchange [3] |

| Molten Globule Intermediate | Compact intermediate with secondary structure but flexible side chains | NMR, circular dichroism [4] |

In Vivo vs. In Vitro Folding: Fundamental Similarities

Recent experimental evidence suggests that for small single-domain water-soluble globular proteins, no fundamental difference exists between in vivo (co-translational) and in vitro refolding. NMR and FRET studies monitoring co-translational structure acquisition have demonstrated that polypeptides remain unstructured during elongation at the ribosome but fold into compact, native-like structures only when the entire domain sequence is available [4] [1].

For multi-domain proteins, however, sequential folding emerges as a crucial mechanism. The N-terminal domains of large proteins can fold before biosynthesis of the entire chain is complete, with domains folding vectorially as their nascent chain portions emerge from the ribosome [4]. This sequential accessibility may help explain how complex multi-domain proteins avoid the combinatorial explosion of possible conformations that Levinthal's paradox describes.

Spontaneous Protein Folding Mechanisms

Determinants of Spontaneous Folding

Spontaneous folding of single-domain globular proteins proceeds through a series of well-defined steps, beginning with the rapid formation of local secondary structures, followed by the acquisition of a molten globule intermediate, and culminating in the precise side-chain packing that characterizes the native state [4] [1]. The rate of this process exhibits a characteristic dependence on protein chain length, with smaller proteins folding more rapidly than larger ones [4].

The critical role of the folding nucleus—a specific set of native contacts that once formed accelerates the acquisition of remaining structure—has been demonstrated through Φ-value analysis, which identifies residues involved in the rate-limiting transition state [1]. This nucleation mechanism provides a structural explanation for how proteins navigate the folding landscape efficiently without exhaustive search.

Experimental Characterization of Spontaneous Folding

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for Spontaneous Folding of Model Proteins

| Protein | Chain Length | Folding Time | Thermodynamic Stability (ΔG) | Key Intermediate States |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small α-helical domains | 20-60 residues | Microseconds | 5-15 kcal/mol | Molten globule [5] |

| Medium mixed α/β proteins | 60-150 residues | Milliseconds | 7-12 kcal/mol | Pre-molten globule [4] |

| Large multi-domain proteins | 150-300 residues | Seconds to minutes | 10-20 kcal/mol | Domain-specific intermediates [4] |

Chaperone-Assisted Folding Mechanisms

The Cellular Folding Environment

Despite the inherent ability of many proteins to fold spontaneously, the crowded intracellular environment presents unique challenges that necessitate chaperone assistance. Molecular chaperones function primarily as aggregation inhibitors rather than catalysts of folding, binding to exposed hydrophobic surfaces on non-native proteins and preventing inappropriate interactions that could lead to misfolding or aggregation [4] [3].

The importance of chaperones becomes particularly evident under cellular stress conditions, where increased concentrations of unfolded proteins threaten proteostasis. Under such conditions, heat shock proteins (HSPs) are upregulated through the heat shock response (HSR) pathway, enhancing the cell's folding capacity and preventing toxic aggregation events [3].

Major Chaperone Systems and Mechanisms

Hsp70 Chaperone Cycle

The Hsp70 system represents one of the most extensively studied chaperone families. Recent molecular dynamics simulations have revealed that Hsp70 facilitates client protein folding through an ATP-dependent cycle involving open-lid and closed-lid states. The closed-lid state interacts with client proteins via specific conserved nonpolar residues, preventing nonnative hydrophobic collapse and allowing more efficient folding upon release [6].

Table 3: Major Chaperone Systems and Their Functions

| Chaperone System | Primary Cellular Role | Key Mechanism | Energy Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp70 | Co-translational folding, stress response | Lid closure prevents hydrophobic collapse | ATP hydrolysis [6] |

| GroEL/GroES | Folding of aggregation-prone proteins | Provides isolated folding compartment | ATP hydrolysis [4] |

| Hsp90 | Activation of signaling proteins | Conformational remodeling of clients | ATP hydrolysis [3] |

| Small HSPs | Stress-induced aggregation prevention | Formation of holding complexes | ATP-independent [3] |

GroEL/GroES Chaperonin System

The GroEL/GroES system provides a physically sequestered environment for protein folding, isolating vulnerable folding intermediates from the crowded cytosol. Contrary to earlier hypotheses suggesting GroEL might act as an "unfoldase," current evidence indicates it does not accelerate the overall folding process but rather serves as a transient trap that binds excess unfolded protein chains, thus preventing their irreversible aggregation [4]. This protective function is particularly critical for proteins with slow folding rates that would otherwise be vulnerable to aggregation during their extended folding time.

Experimental Approaches and Protocols

Quantifying Protein Stability and Folding Kinetics

Accurate measurement of protein stability parameters is essential for both basic research and therapeutic development. The folding free energy (ΔGfold) represents the key thermodynamic parameter describing the balance between folded and unfolded states, typically ranging from 5-15 kcal/mol for most functional proteins [5].

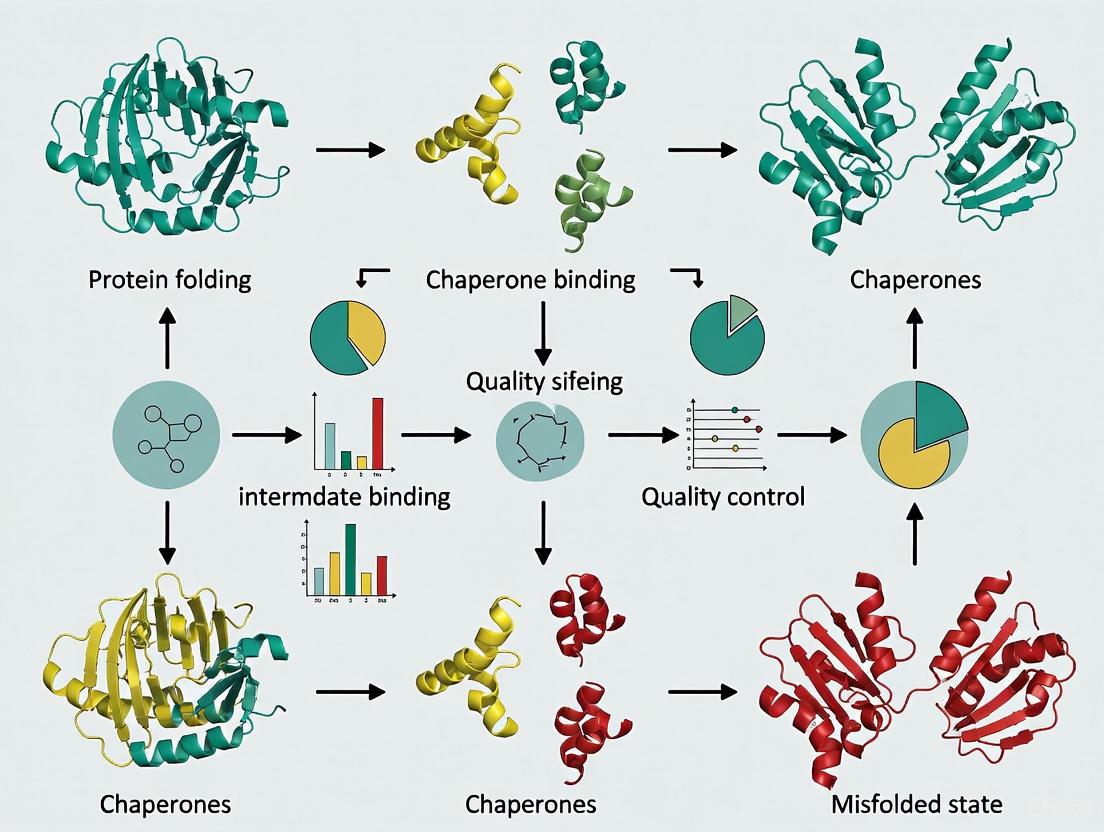

Diagram 1: Protein folding energy landscape showing the transition from unfolded to native state through a partially folded intermediate.

Key Methodologies for Folding Analysis

Equilibrium Unfolding Experiments

Protocol: Chemical Denaturation with Urea/Guanidine HCl

- Prepare protein samples (0.2-0.5 mg/mL) in denaturant solutions spanning 0-8 M urea or 0-6 M guanidine HCl

- Incubate for 2-4 hours at constant temperature to ensure equilibrium

- Monitor unfolding using far-UV circular dichroism (222 nm for α-helical content) or intrinsic fluorescence (tryptophan emission)

- Fit transition data to a two-state or multi-state model to extract Cm (midpoint denaturant concentration) and m-value (cooperativity parameter)

- Calculate ΔGfold using linear extrapolation method: ΔG = ΔG° - m[denaturant] [5]

Kinetic Folding Measurements

Protocol: Stopped-Flow Fluorescence

- Prepare native protein and denatured protein in 6 M guanidine HCl

- Rapidly mix denatured protein with refolding buffer (1:10 dilution) in stopped-flow apparatus

- Monitor fluorescence changes with time resolution of 1-1000 ms

- Fit resulting traces to single or multi-exponential functions to extract folding rates

- Perform experiments at multiple temperatures to obtain activation parameters [5]

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy

Protocol: AFM-based Protein Unfolding

- Immobilize protein constructs on gold surface via cysteine tags

- Approach surface with AFM tip and retract at constant velocity (100-1000 nm/s)

- Record force-extension curves showing characteristic unfolding peaks

- Analyze contour length increases to identify unfolded domains

- Determine unfolding forces and energies from multiple unfolding events [7]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Folding Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Denaturants | Urea, Guanidine HCl | Equilibrium unfolding experiments [5] |

| Fluorescent Dyes | ANS, Sypro Orange | Molten globule detection, aggregation monitoring [4] |

| Proteostasis Regulators | Ver-155008 (Hsp70 inhibitor), PU-H71 (Hsp90 inhibitor) | Chaperone function studies [3] |

| Redox Buffers | GSH/GSSG, DTT | Disulfide bond formation studies [3] |

| Molecular Crowding Agents | Ficoll, Dextran | Mimicking intracellular environment [4] |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, Protease inhibitor cocktails | Preventing proteolytic degradation during folding [5] |

Chaperone-Assisted Refolding Protocols

In Vitro Refolding with GroEL/GroES

Protocol: GroEL/GroES-Mediated Refolding

- Denature client protein in 6 M guanidine HCl for 2 hours

- Rapidly dilute denatured protein into refolding buffer containing GroEL (1:1 molar ratio)

- Incubate for 5 minutes to allow binding of unfolded chains to GroEL

- Add ATP (2 mM) and GroES (2:1 molar ratio to GroEL) to initiate folding

- Monitor refolding kinetics using appropriate spectroscopic methods

- Compare with spontaneous refolding in GroEL-free buffer to quantify chaperone effect [4]

Key parameters to optimize: GroEL-client ratio, ATP concentration, temperature, and refolding time. For aggregation-prone clients, the presence of GroEL/GroES typically increases functional yield by 3-10 fold compared to spontaneous refolding.

Hsp70-Assisted Folding Assay

Protocol: Analyzing Hsp70 Lid Closure Effects

- Prepare Hsp70 constructs (wild-type and lid mutants)

- Bind nucleotide-free Hsp70 to unfolded client protein (e.g., SH3 domain)

- Initiate folding by adding ATP and monitoring client conformation

- Use NMR restraints in molecular dynamics simulations to analyze folding pathways

- Compare folding efficiency between open-lid and closed-lid chaperone states [6]

This protocol has demonstrated that the closed-lid state of Hsp70 interacts with client proteins via specific conserved nonpolar residues, preventing nonnative hydrophobic collapse and enabling more efficient folding upon release.

Diagram 2: Hsp70 chaperone cycle showing ATP-dependent conformational changes that facilitate client protein folding.

Therapeutic Applications and Future Perspectives

The intricate relationship between spontaneous and chaperone-assisted folding has profound implications for human health and disease. Dysproteostasis—the collapse of proper protein homeostasis—is implicated in a growing list of human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, metabolic syndromes, and cancer [3]. In cancer cells, the proteostasis network is frequently reprogrammed to support rapid proliferation and survival under stress conditions, making chaperones attractive therapeutic targets.

Emerging technologies in the protein folding field include deep learning approaches for predicting folding pathways and stability effects of mutations [8], single-molecule techniques for observing real-time folding dynamics [5], and novel small molecule regulators of chaperone function [3]. The FiveFold methodology, which combines predictions from five complementary algorithms, represents a particularly promising approach for modeling conformational ensembles and capturing the dynamic nature of protein folding landscapes [8].

For researchers investigating protein refolding protocols, the experimental framework presented herein provides a foundation for developing optimized refolding strategies that leverage both spontaneous folding principles and chaperone-assisted mechanisms. As our understanding of the intricate interplay between these pathways deepens, so too will our ability to manipulate proteostasis for therapeutic benefit.

Molecular chaperones are highly conserved proteins critical for maintaining cellular protein homeostasis (proteostasis) by facilitating the folding, assembly, and disaggregation of proteins under both normal and stress conditions [9] [10]. They function as essential components of the protein quality control system, preventing the accumulation of misfolded and aggregated proteins associated with numerous diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, cancer, and inflammatory conditions [9] [11] [10]. This application note details the experimental approaches for studying four major chaperone families—HSP70, HSP90, HSP60/Chaperonins, and small Heat Shock Proteins (sHSPs)—providing structured protocols and quantitative data to support research and drug discovery efforts.

The HSP70 Chaperone System

Functional Mechanism and Experimental Analysis

HSP70 chaperones operate through an ATP-dependent cycle of substrate binding and release, assisted by co-chaperones including J-domain proteins (JDPs) that target Hsp70s to substrates and nucleotide exchange factors (NEFs) that regulate complex lifetime [10]. The flexible lid domain undergoes conformational changes between open and closed states, which is crucial for client protein interaction [12] [6].

Table 1: Key Functional Parameters of HSP70 Chaperones

| Parameter | Experimental Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Client Protein Folding Efficiency | SH3 folds more effectively after sampling conformational space within closed-lid Hsp70 | NMR restraint-assisted MD simulations of nucleotide-free Hsp70 [12] [6] |

| Interaction Mechanism | Specific, highly conserved nonpolar residues prevent nonnative hydrophobic collapse | All-atom MD simulations with SH3 client [12] |

| Cellular Role | Assists de novo folding of 10-20% of bacterial proteins; higher percentage in eukaryotes | Cellular functional studies [10] |

Protocol: Analyzing HSP70 Client Folding Using Molecular Dynamics

Purpose: To investigate HSP70-assisted client protein folding through computational simulations. Applications: Mechanism of action studies, drug target identification, and mutation impact analysis.

Methodology:

- System Setup:

Simulation Execution:

Data Analysis:

- Quantify client protein folding efficiency by measuring native state formation probability.

- Analyze Hsp70-client interactions, focusing on specific conserved nonpolar residues [12].

- Determine the role of closed-lid state in preventing nonnative hydrophobic collapse of client upon chaperone release [12] [6].

The HSP90 Chaperone System

Functional Roles in Cellular Stress and Disease

HSP90 functions as a dimeric molecular chaperone complex that interacts with specific client proteins, particularly in signal transduction pathways. Unlike HSP70, HSP90 shows specialization for regulatory proteins including kinases, transcription factors, and steroid hormone receptors [10]. During chronic stress adaptation, Hsp90 couples cell size increase to augmented translation in a process termed the 'rewiring stress response', which is essential for cellular adaptation to prolonged mild stresses [13].

Table 2: HSP90 in Chronic Stress Adaptation

| Experimental Context | HSP90 Function | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic mild stress (up to 2 weeks) in mammalian cells | Essential for coupling cell size increase to augmented translation | Increased cellular resilience to persistent and subsequent stresses [13] |

| Adaptation to proteotoxic stress (e.g., heat) | Supports Hsf1-mediated 'rewiring stress response' | Adaptive cell size increase and total protein scaling [13] |

| Failure of HSP90 function | Impaired stress adaptation | Potential contribution to aging processes [13] |

The HSP60/Chaperonin System

Structural and Functional Characteristics

HSP60 (chaperonin 60) forms large double-ring barrel structures that provide a central cavity for protein folding. Group I chaperonins (HSP60) are found in eubacteria and eukaryotic organelles, while Group II chaperonins (TRiC/CCT) reside in the eukaryotic cytosol [9] [14]. Mammalian HSP60 exists primarily as a single heptameric ring that converts to a tetradecameric double-ring structure in the presence of ATP and forms a football-type complex with the co-chaperone HSP10 [15].

Unique Nucleotide Specificity of HSP60

Unlike bacterial GroEL, mammalian HSP60 exhibits dual nucleotide specificity with both ATPase and GTPase activities, suggesting distinct functional roles for these activities in chaperone function [15].

Table 3: Comparative Nucleotide Hydrolysis in HSP60

| Parameter | ATPase Activity | GTPase Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Allosteric Kinetics | Two apparent transitions with Hill coefficients 1.76 (first) and 5.52 (second) | Single sigmoidal curve with Hill coefficient ~2.3 [15] |

| HSP10 Effect | Suppressed hydrolysis activity | No suppression of hydrolysis [15] |

| Structural Outcome | Stable double-ring structure with HSP10 | Predominantly single-ring structures [15] |

| Functional Role | Productive refolding of denatured substrates | Supporting function in protein folding [15] |

Protocol: Assessing HSP60 Nucleotide-Dependent Oligomerization

Purpose: To characterize HSP60 oligomeric states and complex formation in response to different nucleotides. Applications: Chaperonin mechanism studies, nucleotide analog screening, and therapeutic development.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Purify recombinant wild-type HSP60 (porcine cytosolic source described) [15].

- Prepare nucleotide solutions: ATP and GTP across concentration range (0-1.0 mM).

- Include HSP10 co-chaperone for complex formation studies.

Transmission Electron Microscopy:

- Incubate HSP60 (0.1 mg/mL) with nucleotides (ATP or GTP, 1 mM) with/without HSP10 for 10 minutes at 25°C [15].

- Apply 5 μL samples to carbon-coated grids, negative stain with 2% uranyl acetate.

- Acquire images using TEM at appropriate magnification (e.g., 50,000×).

Statistical Structural Analysis:

- Classify >100 molecules per condition into structural categories: single-ring (HSP60₇), double-ring (HSP60₁₄), bullet-type complex (HSP60₁₄-HSP10₇), football-type complex (HSP60₁₄-(HSP10₇)₂) [15].

- Calculate percentage distribution of oligomeric states for each condition.

- Expected outcome: ~70% double-ring structures with ATP+HSP10 vs. predominantly single-ring with GTP+HSP10 [15].

Small Heat Shock Proteins (sHSPs)

Characteristics and Neuroprotective Functions

Small heat shock proteins (12-43 kDa) constitute ATP-independent chaperones that prevent irreversible aggregation of denaturing proteins through holder chaperone activity [11] [16]. Humans encode ten sHSPs (HSPB1-HSPB10) with varying tissue distribution and expression patterns [11]. Recent research demonstrates that cytosolic sHSPs are imported into the mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS) under basal conditions, where they operate as molecular chaperones [17].

Table 4: Small HSP Functions in Neurological Disorders

| sHSP | Alternative Name | Neurological Disease Associations | Regulation in Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSPB1 | Hsp27 (human)/Hsp25 (mouse) | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Multiple Sclerosis | Upregulated [11] |

| HSPB5 | Alpha-B crystallin | Alexander's disease, Alzheimer's, Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson's | Upregulated [11] |

| HSPB8 | Hsp22 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer's, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease | Variably regulated [11] |

Protocol: Mitochondrial Import Assay for sHSPs

Purpose: To investigate the subcellular localization and mitochondrial import of small heat shock proteins. Applications: Studying mitochondrial proteostasis, neurodegenerative disease mechanisms, and stress response pathways.

Methodology:

- Mitochondrial Isolation:

- Culture mammalian cells (HeLa, C2C12, or primary lymphoblasts) to 80-90% confluence.

- For stress conditions, apply heat shock (42-45°C for 20-60 minutes) then collect cells immediately.

- Isolate mitochondria using differential centrifugation with isotonic buffers [17].

Proteinase K Protection Assay:

- Divide mitochondrial samples into three aliquots:

- Intact mitochondria: No detergent

- Swollen mitochondria: + Hypo-osmotic buffer (e.g., 10 mM HEPES)

- Disrupted mitochondria: + Detergent (e.g., 1% Triton X-100)

- Treat all samples with proteinase K (50-100 μg/mL) for 15-30 minutes on ice.

- Stop reaction with PMSF (2 mM) and prepare samples for immunoblotting [17].

- Divide mitochondrial samples into three aliquots:

Analysis:

- Perform immunoblotting with antibodies against sHSPs (HSPB1, HSPB5, HSPB8).

- Include controls for mitochondrial compartments: TOM20 (outer membrane), TIMM23 (inner membrane), HSP60 (matrix).

- Interpretation: IMS-localized sHSPs protected in intact mitochondria but degraded upon swelling; matrix proteins remain protected until detergent treatment [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for Chaperone Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Client Proteins | SH3 domain, misfolded luciferase, acid-denatured GFP | Substrates for folding and refolding assays [12] [15] |

| Nucleotide Analogs | ATPγS, GTPγS, AMP-PNP | Studying ATPase/GTPase cycles and conformational states [15] |

| Protease Assay Components | Trypsin, Proteinase K, PMSF | Protease sensitivity assays for complex formation [15] [17] |

| Structural Biology Tools | Negative stain EM, Crosslinkers, NMR restraints | Oligomeric state analysis and structural studies [12] [15] |

| Cell Culture Models | HeLa, C2C12, primary lymphoblasts | Mitochondrial import and stress response studies [17] |

The sophisticated experimental approaches detailed in this application note enable researchers to dissect the complex mechanisms of major chaperone families. From computational simulations of HSP70 conformational dynamics to biochemical assessments of HSP60 nucleotide specificity and mitochondrial import assays for sHSPs, these protocols provide robust methodologies for advancing our understanding of chaperone-assisted protein refolding. The growing evidence of chaperone involvement in neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and aging highlights the importance of these systems as therapeutic targets, necessitating continued methodological development in the field.

Molecular chaperones constitute a diverse network of proteins essential for maintaining cellular proteostasis. They facilitate the proper folding, assembly, and localization of other proteins, preventing aggregation and mediating the recovery of misfolded states. Unlike enzymes with specific substrates, chaperones must recognize a vast array of client proteins primarily through exposed hydrophobic regions that are typically buried in the native state. The molecular mechanisms underlying this recognition—how chaperones identify their substrates, the kinetic pathways of binding, and the structural consequences for the client protein—form the foundation of chaperone biology. This application note explores the structural principles of chaperone-substrate interactions, detailing key experimental methodologies and providing quantitative insights into these fundamental processes. Understanding these mechanisms is critical for developing therapeutic interventions for diseases of protein misfolding and for improving recombinant protein production in biotechnology.

Fundamental Recognition Mechanisms

Key Biophysical Principles of Recognition

Chaperone-client interactions are characterized by several unifying biophysical principles that enable their broad specificity and functional efficacy.

- Weak, Hydrophobic Interactions: The binding interfaces between chaperones and their clients are typically characterized by weak affinity and transient interactions, predominantly mediated by hydrophobic contacts [18]. This low binding affinity is crucial as it allows the chaperone to recognize a wide range of sequences while permitting client release once folding is achieved.

- Hierarchy of Affinities: A key feature of productive chaperone function is the existence of a affinity hierarchy, where the chaperone has higher affinity for unfolded states than for the native, folded state of the client [18]. This ensures that folding, driven by the client's intrinsic hydrophobic collapse, readily outcompetes chaperone binding, facilitating release of the functional protein.

- Plastic Binding Grooves: Structural studies reveal that chaperone substrate-binding domains often display significant plasticity. For example, the substrate-binding groove of Hsp70 chaperones can accommodate extended conformations of various hydrophobic sequences, contributing to their promiscuity [19].

Predominant Pathway: Conformational Selection

A pivotal concept in understanding chaperone specificity is the mechanism by which the chaperone engages with its client. Recent structural and kinetic evidence strongly supports conformational selection as a primary mechanism for several major chaperone families.

- Hsp70 Conservation: Solution NMR studies quantifying the flux along binding pathways have established that both bacterial and human Hsp70 chaperones interact with clients by selectively binding the unfolded state from a pre-existing ensemble of interconverting structures [20]. The chaperone does not induce unfolding but rather selects for client conformations that are already unfolded or extended.

- Structural Basis for Selection: The substrate-binding domain (SBD) of Hsp70 contains a hydrophobic pocket that can only accommodate an extended polypeptide chain. This imposes a structural constraint that inherently selects against compact, folded structures [20].

- Functional Advantage: This mechanism allows Hsp70 to avoid inappropriate interactions with natively folded, functional proteins, thereby minimizing disruption to the cellular proteome while effectively targeting proteins in non-native states [20].

The following diagram illustrates the conformational selection mechanism used by Hsp70 chaperones.

Comparative Mechanisms Across Chaperone Classes

While conformational selection is a major mechanism, different chaperone classes employ variations on this theme, tailored to their specific cellular roles.

- Spy: A Permissive Scaffold: The bacterial chaperone Spy operates without ATP hydrolysis. It employs an amphiphilic, flexible binding surface that initially engages clients via electrostatic interactions, followed by stabilization through hydrophobic contacts [18]. Its concave binding surface allows the client to explore conformational space while protected from aggregation. Folding proceeds on the chaperone surface until the native state's hydrophobic core forms, destabilizing the chaperone-client complex and triggering release [18].

- Synthetic Nano-Chaperones (SNCPs): Bio-inspired porous nanoparticles have been engineered to mimic chaperone function. These SNCPs provide a tunable internal hydrophobic environment that stabilizes specific secondary structures, such as the α-helical conformation of a model p53 peptide [21]. The hydrophobicity of the internal surface directly influences the secondary structure of the encapsulated peptide, demonstrating how environmental polarity can guide folding.

Table 1: Key Structural Features in Chaperone-Substrate Recognition

| Chaperone | Recognition Mechanism | Binding Site Characteristics | Key Client Features Recognized |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp70 | Conformational Selection [20] | Hydrophobic groove in SBD; plastic surface [19] | Extended conformations with hydrophobic cores (Ile, Leu, Val) [20] |

| Spy | Hierarchical binding (electrostatic, then hydrophobic) [18] | Flexible, amphiphilic concave surface [18] | Unfolded states; promiscuous binding [18] |

| Synthetic Nano-Chaperone | Hydrophobic encapsulation [21] | Tunable internal hydrophobicity of porous nanoparticle [21] | Peptide sequence; stabilizes α-helical structures [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Recognition

NMR Spectroscopy for Detecting Conformational Selection

Solution Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a powerful technique for studying chaperone-client interactions at atomic resolution under physiological conditions. It allows researchers to distinguish between folded, unfolded, and chaperone-bound states of a protein and to quantify the kinetics of their interconversion [18] [20].

Protocol: Characterizing Hsp70-Substrate Interactions via Methyl TROSY

Sample Preparation:

- Isotopic Labeling: Produce (^{15})N-labeled or (^{13})C(^{1})H(^{3})-methyl-labeled (Ile, Leu, Val) client protein in E. coli. For larger chaperones like Hsp70, perdeuteration with specific methyl labeling is essential to reduce relaxation effects and enhance signal [20].

- Protein Purification: Purify chaperone (e.g., Hsp70) and client protein using standard affinity and size-exclusion chromatography.

- Buffer Conditions: Use an appropriate physiological buffer (e.g., 20-50 mM HEPES/KOH, pH 7.0-7.5, 50-150 mM KCl, 5-10 mM MgCl(_2)).

NMR Data Acquisition:

- Titration Experiment: Acquire a series of (^{1})H-(^{15})N Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (HSQC) or methyl-TROSY spectra of the labeled client protein while titrating in unlabeled chaperone.

- Spectra Recording: Monitor chemical shift perturbations, line broadening, and the disappearance of cross-peaks corresponding to the free client as the chaperone is added. The appearance of new peaks indicates the bound state.

Data Analysis:

- Pathway Quantification: Analyze the NMR kinetic data to determine the flux along conformational selection versus induced fit pathways. This involves quantifying the populations of free and bound states and their exchange rates [20].

- Structural Insights: The specific perturbations observed reveal the client residues involved in binding and the degree of unfolding upon chaperone engagement.

Circular Dichroism (CD) for Monitoring Secondary Structure

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy is used to monitor changes in the secondary structure of a client protein upon interaction with a chaperone or within a synthetic chaperone environment [21].

Protocol: Assessing Secondary Structure Changes in SNCPs

Sample Preparation:

- Encapsulation: Incubate the peptide (e.g., p53pep) with the synthetic nano-chaperone (SNCP) in aqueous buffer to form the SNCP-peptide complex [21].

- Control Samples: Prepare samples of the free peptide in aqueous solution and in a helix-inducing solution (e.g., 30% trifluoroethanol) for reference.

CD Measurement:

- Parameter Setup: Use a CD spectropolarimeter with a temperature-controlled cuvette. Standard parameters include a wavelength range of 190-260 nm, a bandwidth of 1 nm, and a path length of 0.1 cm.

- Data Collection: Record the CD spectrum of each sample at room temperature. For thermal stability, record spectra at increasing temperatures (e.g., from 25°C to 75°C).

Data Analysis:

- Spectral Interpretation: Analyze the resulting spectra for characteristic signatures: double negative minima at ~208 nm and ~222 nm indicate α-helical structure, while a single negative minimum near 218 nm suggests β-sheet, and a negative peak around 200 nm indicates random coil.

- Quantification of Helicity: Use algorithms like the CONTIN/LL program to deconvolute the spectra and estimate the relative percentage of different secondary structures [21].

The experimental workflow for analyzing chaperone-client interactions is summarized below.

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful research program in chaperone-substrate recognition relies on a toolkit of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential solutions for key experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Chaperone Recognition Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope-labeled Amino Acids (e.g., (^{15})N, (^{13})C) | Enables NMR detection of protein structure and dynamics in solution. | (^{13})C(^{1})H(^{3})-methyl labeling of Isoleucine, Leucine, Valine for methyl-TROSY on large proteins [20]. |

| Refolding Buffers & Additives | Promote correct folding and prevent aggregation during refolding assays. | L-arginine (ArgHCl): Acts as an aggregation suppressor during dilution refolding [22]. Low denaturant concentrations (e.g., 0.5-1 M Urea): Can stabilize folding intermediates [22]. |

| Synthetic Nano-Chaperones (SNCPs) | Artificial system to study and control peptide folding; delivery vehicle. | Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles with inner surface modified with octyl groups (SNCP8) to create a hydrophobic internal environment that stabilizes α-helical structure [21]. |

| Model Client Proteins | Well-characterized substrates for in vitro chaperone activity assays. | Unfolded proteins/peptides with hydrophobic stretches (e.g., sequences enriched in Ile, Leu, Val) for Hsp70 binding studies [19] [20]. |

| Nucleotide Analogs | Probing the ATP-dependent chaperone cycle (e.g., of Hsp70). | Non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs (e.g., ATPγS) to trap the ATP-bound state of Hsp70 and study its effect on substrate affinity [20]. |

Application Notes & Technical Data

Quantitative Insights into Binding and Refolding

The efficiency of chaperone-mediated recognition and refolding can be quantified through various parameters, providing a basis for optimizing experimental conditions.

Table 3: Quantitative Data on Chaperone Activity and Refolding

| Parameter / System | Reported Value / Efficiency | Experimental Context / Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Hsp70-Substrate Binding Affinity (Kd) | Weak, micromolar range (e.g., ~3 μM for unfolded Fyn SH3 bound to Spy) [18] | Weak affinity prevents kinetic trapping and allows for client release upon folding. |

| Spy: Folded vs. Unfolded Client Affinity | Kd (unfolded) ~3 μM; Kd (folded) ~50 μM [18] | Demonstrates the critical affinity hierarchy that drives the folding pathway. |

| Protein Refolding Yield (Dilution + Additives) | ≥80% recovery of active protein [22] | Significant improvement over conventional methods, highlighting the utility of additives like ArgHCl. |

| Protein Refolding Yield (Microfluidic Chip) | ≥70% recovery [22] | Rapid mixing and controlled diffusion reduce aggregation, enabling higher protein concentrations and shorter refolding times. |

| Chaperone Network Throughput | Mediates folding of ~62% of total cellular protein flux [23] | Underlines the massive scale and essential nature of chaperone function in proteome maintenance. |

Practical Considerations for Protocol Implementation

- Optimizing Refolding Conditions: When refolding proteins from inclusion bodies, the critical parameter is to minimize aggregation at intermediate denaturant concentrations. The use of a slow, graded dialysis or the incorporation of chemical additives like arginine can dramatically improve yields by suppressing off-pathway aggregation [22].

- Handling Synthetic Nano-Chaperones: For SNCPs, the hydrophobicity of the internal surface is a critical design parameter. Functionalization with longer aliphatic chains (e.g., octyl groups in SNCP8) creates a more hydrophobic environment, which was shown to favor the formation and stabilization of α-helical structure in a model peptide over β-sheet or random coil [21].

- NMR Sample Requirements: For studies aimed at distinguishing conformational selection from induced fit, high-quality, stable isotope-labeled samples are non-negotiable. The application of advanced NMR techniques like methyl TROSY is crucial for studying the large complexes formed by chaperones and their clients [20].

{article}

The Ribosome's Role: Trigger Factor and Cotranslational Folding Pathways

The ribosome is not merely a synthetic machine for polypeptide production but a central hub for coordinating the initial stages of protein folding. This process, known as cotranslational folding, is guided by the intricate architecture of the ribosome and facilitated by molecular chaperones, with Trigger Factor (TF) being the primary ribosome-associated chaperone in bacteria. TF docks near the polypeptide exit tunnel, creating a protected folding cradle where nascent chains can begin their structural organization while being shielded from the crowded cellular environment [24]. Recent advances reveal that the ribosome and its associated chaperones direct folding along pathways that are fundamentally distinct from refolding of full-length proteins in solution. This application note details the mechanisms of cotranslational folding, summarizes key quantitative findings, and provides protocols for studying these processes, providing a critical resource for researchers in protein science and therapeutic development.

Protein folding in vivo begins during synthesis on the ribosome, a vectorial process where the nascent chain (NC) emerges sequentially from the N- to C-terminus. Unlike refolding from denaturant, where the entire sequence is simultaneously available, cotranslational folding is constrained by the physical context of the ribosome. The narrow, negatively charged ribosome exit tunnel can accommodate α-helices but not larger tertiary structures, while the ribosome surface itself can thermodynamically destabilize folding domains [25]. This delay in folding can prevent unproductive interactions and misfolding, particularly in multi-domain proteins.

The first cellular component to encounter the majority of nascent polypeptides in bacteria is Trigger Factor. This highly abundant chaperone binds to the large ribosomal subunit near the exit tunnel and engages a wide spectrum of nascent chains [26] [24]. The functional cooperation between the ribosome and TF establishes a protected compartment—a molecular cradle—where nascent polypeptides can explore conformational space while being protected from proteolysis and aggregation [24]. Understanding the principles of this coordinated folding is essential for fundamental biology and has direct applications in mitigating aggregation-related diseases and optimizing the production of complex recombinant proteins.

Mechanism of Trigger Factor and Chaperone Coordination

Structural Basis of Trigger Factor Function

Trigger Factor is a 48-kDa modular protein consisting of three domains: an N-terminal ribosome-binding domain, a middle peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (PPIase) domain, and a C-terminal domain that serves as the primary nascent chain binding region [26]. The crystal structure of TF in complex with the ribosome reveals a unique "crouching dragon" conformation, where the chaperone arches over the exit site of the ribosomal tunnel [24]. This arrangement creates a protected, shielded space of approximately 55 x 55 Å, sufficient to accommodate folding intermediates of small protein domains.

The N-terminal domain of TF is both necessary and sufficient for ribosome binding, primarily interacting with ribosomal protein L23 [26] [24]. This docking position allows the C-terminal arms of TF to sample the emerging nascent chain. The affinity of TF for the ribosome is remarkably high, with a dissociation constant (KD) of approximately 1 μM, ensuring that TF is present in stoichiometric complexes with ribosomes under physiological conditions [26].

Multimodal Recognition of Nascent Chain Features

TF employs multiple mechanisms to interact with a diverse range of substrate proteins, demonstrating remarkable binding versatility:

- Recognition of Hydrophobic Regions: TF exhibits a strong preference for nascent chains exposing linear hydrophobic segments. The residence time of TF on a nascent chain correlates with the presence and exposure of these hydrophobic regions, with some interactions lasting up to 111±7 seconds [26].

- Interaction with Folded Domains: Surprisingly, TF can also bind folded domains, such as that of the ribosomal protein S7, indicating an alternative mode of action that may extend beyond chaperoning unfolded chains to include roles in ribosome assembly [26].

- Chaperone Coordination: TF acts as a gatekeeper at the ribosome exit site. Recent research demonstrates that TF binding is disfavored very close to the ribosome, allowing initial folding events to occur. TF recognizes compact folding intermediates that expose extensive unfolded surfaces and subsequently dictates access for the downstream chaperones DnaJ and DnaK [27]. This collaboration allows the chaperone network to protect incipient structure in the nascent polypeptide well beyond the ribosome exit tunnel.

Quantitative Data on Trigger Factor Interactions

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters of Trigger Factor Interactions with Nascent Chains and Ribosomes

| Parameter | Value | Experimental System | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| TF-Ribosome Binding KD | ~1 μM | E. coli [26] | High affinity ensures TF is ribosome-associated. |

| Cellular TF Concentration | ~50 μM | E. coli [26] | TF is in excess over ribosomes (~30 μM). |

| TF Residence Time on Ribosome | t½ ~ 10-14 s | In vitro reconstitution [26] | Rapid binding and release cycle at exit tunnel. |

| TF Residence Time on Nascent Chain | 111 ± 7 s (for Luciferase) | In vitro translation [26] | Much longer than ribosome binding, allows multiple TF binding events. |

| Chain Length for Domain Folding | ~330 amino acids (GEF-G domain) | Arrest Peptide Profiling [28] | Defines the point at which a complete domain is extruded and can fold. |

Table 2: Nascent Chain Features Influencing Trigger Factor Binding Affinity

| Nascent Chain Feature | Effect on TF Binding | Example Protein |

|---|---|---|

| Extended hydrophobic segments | Strong increase in binding affinity and residence time | Firefly Luciferase [26] |

| Lack of hydrophobic segments | Weak or transient interaction | Basic, hydrophilic proteins [26] |

| Signal sequences | Strong binding | pOmpA (secretory protein) [26] |

| Signal anchor sequences | No significant binding | FtsQ (membrane protein) [26] |

| Non-linear hydrophobic patches | Intermediate binding | Proteins with collapsed folding intermediates [26] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Arrest Peptide Profiling for Cotranslational Folding

Principle: This high-throughput method uses a force-sensitive arrest peptide (AP) from the E. coli SecM protein to detect co-translational folding in live cells. Nascent chain folding generates mechanical force that pulls the AP from the ribosome exit tunnel, relieving translational arrest and enabling expression of a downstream reporter [28].

Procedure:

- Library Construction: Clone the gene of interest (GOI) fused in-frame to the SecM AP sequence and a fast-folding reporter (e.g., msGFP). Generate a truncated library of the GOI using time-dependent exonuclease digestion to create variants of different lengths.

- Dual Reporter System: Use a plasmid with two independent expression cassettes: one for the GOI-AP-msGFP fusion and another for an mCherry control to normalize for expression variation.

- Expression and Cell Sorting: Express the library in E. coli and analyze cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Gate cells based on the log(IGFP/ImCherry) ratio, which reports on folding-induced arrest release.

- Deep Sequencing and Analysis: Isclude DNA from each sorted population and deep-sequence the 3'-ends of the library inserts. Calculate an "AP score" for each truncation variant based on its distribution across the sorting gates. A peak in the AP score profile indicates a co-translational folding event at a specific nascent chain length.

Applications: Delineating folding pathways of structurally intricate proteins, defining the exact chain length required for domain folding, and studying the impact of chaperone ablation on folding pathways with codon resolution [28].

Protocol: Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) on Ribosome-Nascent Chain Complexes (RNCs)

Principle: HDX-MS measures the exchange of backbone amide hydrogens with deuterium in the solvent. The rate of exchange is exquisitely sensitive to protein conformation, with structured regions exchanging more slowly. This allows probing the local folding status of a nascent chain on the ribosome at peptide-level resolution [25].

Procedure:

- RNC Preparation: Engineer and express DHFR (or protein of interest) constructs truncated at specific codon positions, followed by a strong ribosome stall sequence. Purify stable RNCs from E. coli using sucrose cushion centrifugation and size-exclusion chromatography.

- Deuterium Labeling: Expose purified RNCs to deuterated buffer for defined time points (e.g., 10 s, 100 s, 1000 s). Quench the reaction with low pH and low temperature.

- Proteolysis and LC-MS/MS Analysis: Digest the entire sample (including ribosomal proteins and chaperones) with an acid-tolerant protease (e.g., pepsin). Separate the resulting peptides using liquid chromatography and analyze by mass spectrometry.

- Data Processing: Identify peptides and calculate their deuterium uptake. Compare the deuteration patterns of nascent chain peptides across different RNC lengths and to a fully folded, released control.

Applications: Revealing non-native folding intermediates on the ribosome, mapping the path of the emerging polypeptide, and studying the structural impact of chaperones like TF on nascent chains without disrupting the complex [25].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Arrest Peptide Profiling Workflow

Diagram Title: Arrest Peptide Profiling for Cotranslational Folding Analysis

HDX-MS Workflow for RNC Analysis

Diagram Title: HDX-MS Workflow for Ribosome-Nascent Chain Complexes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Studying Cotranslational Folding

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Features & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Trigger Factor Variants (e.g., Cysteine mutants for labeling) | Site-specific labeling with fluorophores (e.g., NBD, BADAN) to monitor conformational changes and binding kinetics. | Select mutants (e.g., TF14, TF150, TF326, TF376) for labeling different domains [26]. |

| Ribosome-Nascent Chain Complexes (RNCs) | Defined intermediates for biochemical and biophysical studies (e.g., HDX-MS, fluorescence spectroscopy). | Use stall sequences (e.g., SecM variants) for efficient and stable RNC purification [25]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (NBD, BADAN, ANS) | Environmentally sensitive probes for monitoring substrate binding and conformational changes in TF and nascent chains. | NBD fluorescence increases in hydrophobic environments, reporting on TF-substrate interaction [26]. |

| Arrest Peptide (AP) Reporter Plasmids | High-throughput detection of co-translational folding forces in live cells (AP Profiling). | Ensure constructs contain SecM AP, a candidate protein, and a rapidly folding reporter (e.g., msGFP) [28]. |

| Deuterated Buffers | Solvent for HDX-MS experiments to measure hydrogen-deuterium exchange in proteins and complexes. | Critical for quantifying backbone amide protection and thus protein conformation and dynamics [25]. |

The ribosome provides a specialized platform that actively shapes the folding landscape of nascent proteins. Through its physical constraints and partnership with a dedicated chaperone network led by Trigger Factor, it ensures that the complex process of protein maturation proceeds with high fidelity and efficiency. The experimental approaches detailed here—from high-throughput in vivo profiling to peptide-resolution structural proteomics—provide a powerful toolkit for dissecting these pathways. As these methods continue to evolve, they will yield deeper insights into protein homeostasis, with broad implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing novel biotherapeutic strategies.

{/article}

Cellular protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, is fundamental to cellular health and functionality, ensuring a stable and functional proteome capable of executing essential life tasks [29]. Molecular chaperones are pivotal guardians of the proteome, assisting in protein folding, preventing aberrant protein aggregation, and maintaining proteostasis balance [30] [29]. These chaperones can be broadly classified into two major categories based on their energy requirements: ATP-dependent chaperones, which consume ATP to fuel cycles of substrate binding, folding, and release, and ATP-independent chaperones, which operate without energy consumption, primarily preventing aggregation through stable substrate binding [31] [30] [32]. Understanding the distinct mechanisms, structures, and functional roles of these systems is crucial for developing targeted therapeutic strategies for diseases linked to proteostasis collapse, such as neurodegenerative disorders and cancer [29] [33]. This note details the core principles, experimental methodologies, and key reagents for studying these essential cellular components.

Core Principles and Key Distinctions

ATP-Dependent Chaperone Systems

ATP-dependent chaperones utilize ATP binding and hydrolysis to power conformational changes that drive iterative cycles of client protein binding, folding, and release [31] [33]. They often act as "foldases" by directly facilitating the refolding of non-native substrates [32].

Table 1: Major ATP-Dependent Chaperone Families and Their Functions

| Chaperone Family | Key Representatives | ATPase Cycle Features | Primary Cellular Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp70 System | DnaK (prokaryotic), Hsp70 (eukaryotic) | Cycle regulated by Hsp40 (J-protein) and NEFs (e.g., GrpE) [31]. | Stabilization of nascent chains, prevention of aggregation, translocation across membranes [31]. |

| Hsp90 System | Hsp90α, Hsp90β, GRP94, TRAP1 [33] | Conformational cycle between open and closed states; regulated by co-chaperones (p23, Aha1) [31] [33]. | Maturation of specific "client" proteins like transcription factors and signaling kinases [31] [33]. |

| Chaperonins (Hsp60) | GroEL (bacteria), HSP60 (eukaryotes) | Folding occurs in an isolated Anfinsen cage upon GroES binding and ATP hydrolysis [31]. | Folding of proteins with complex α/β topologies; forceful unfolding and encapsulation of substrates [31]. |

| Hsp100 Unfoldases/Disaggregases | ClpB, Hsp104, ClpX | Hexameric AAA+ ATPases; sequential or concerted ATP hydrolysis [31]. | Protein disaggregation (with Hsp70), unfolding and translocation to proteases (e.g., ClpP) [31]. |

ATP-Independent Chaperone Systems

ATP-independent chaperones function without energy consumption, primarily acting as "holdases" that rapidly bind to non-native proteins to prevent their aggregation, especially under stress conditions [30] [32]. They are crucial under ATP-depleting stress conditions (e.g., oxidative stress) and in cellular compartments with limited ATP availability, such as the bacterial periplasm [32]. Notably, recent research has revealed that some ATP-independent chaperones, such as Spy, can also exhibit "foldase" activity, allowing certain substrates to reach their native state while still chaperone-bound [34].

Table 2: Characteristics of Select ATP-Independent Chaperones

| Chaperone | Class / Size | Activation Mechanism | Mode of Action / Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Heat Shock Proteins (sHSPs) | e.g., HSPB1 (HSP27), HSPB5; 12-43 kDa oligomers [33] | Oligomeric rearrangement and increased substrate affinity upon stress [33] [32]. | Holdase; broad substrate specificity; first line of defense against aggregation [33] [32]. |

| Spy | Periplasmic chaperone [34] | Conformational dynamics fine-tune substrate affinity [32]. | Substrate-specific action (holdase or foldase) dictated by affinity for non-native states [34]. |

| Trigger Factor (TF) | Ribosome-associated chaperone [25] | Binds ribosome and engages nascent chains co-translationally [25]. | Holdase/foldase; prevents aggregation of nascent polypeptides; can allow folding while bound [25]. |

| HdeA/HdeB | Periplasmic, acid-activated [32] | Conformational activation and dimer dissociation at low pH [32]. | Holdase; prevents aggregation in the acidic environment of the stomach [32]. |

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental operational cycles of these two chaperone systems.

Experimental Protocols for Chaperone Mechanism Analysis

Protocol: Analyzing Cotranslational Folding with HDX-MS

This protocol, adapted from studies on E. coli dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), details how to resolve chaperone-assisted protein folding on the ribosome at peptide resolution using Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) [25].

1. Preparation of Stalled Ribosome-Nascent Chain Complexes (RNCs): - Cloning: Generate DNA constructs encoding the protein of interest (e.g., DHFR) truncated at specific lengths, fused C-terminally to a strong ribosome stall sequence (e.g., an 8-amino acid stalling sequence) [25]. - Expression and Purification: Express the constructs in an appropriate bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli). Purify stalled RNCs using sucrose density gradient centrifugation or affinity-based methods. Verify stalling and homogeneity by checking puromycin insensitivity and via SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry analysis [25].

2. Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange (HDX) Labeling: - Deuteration: Initiate the exchange reaction by diluting the purified RNCs into deuterated buffer (e.g., D₂O-based refolding buffer). Perform labeling for a series of time points (e.g., 10 s, 100 s, 1000 s) at a controlled temperature (e.g., 25°C) to capture different exchange kinetics [25]. - Quenching: Stop the exchange reaction by lowering the pH and temperature. A typical quenching solution is ice-cold buffer at pH ~2.5 [25].

3. Sample Processing and Mass Spectrometry Analysis: - Digestion: Rapidly digest the quenched sample with an immobilized acid-tolerant protease (e.g., pepsin) [25]. - LC-MS/MS Analysis: Separate the resulting peptides using liquid chromatography under quenched conditions. Analyze the peptides using high-resolution mass spectrometry to determine the mass increase due to deuterium incorporation for each peptide [25].

4. Data Interpretation: - Mapping Protection: Compare the deuterium uptake of peptides from the nascent chain across different RNC lengths and labeling times. Peptides involved in stable structure or protected by chaperone binding will show reduced deuterium uptake compared to unstructured regions [25]. - Pathway Definition: Identify the order of structure formation by observing which regions become protected from exchange at specific nascent chain lengths, thereby defining the cotranslational folding pathway and the impact of associated chaperones like Trigger Factor [25].

Protocol: Assessing Chaperone Activity via Aggregation Prevention

This protocol measures the ability of a chaperone to prevent the aggregation of a model substrate under stress conditions (e.g., heat or chemical denaturation) and is applicable to both ATP-dependent and ATP-independent chaperones [32] [34].

1. Experimental Setup: - Reagents: Prepare assay buffer, the chaperone of interest, and a model substrate protein known to aggregate upon thermal or chemical denaturation (e.g., citrate synthase, insulin) [32] [34]. - Instrumentation: Use a spectrophotometer or fluorometer equipped with a temperature-controlled cuvette holder and a stirrer. Light scattering at 360 nm or an increase in fluorescence of dyes like Thioflavin T can monitor aggregation [32].

2. Aggregation Assay: - Control Reaction: In a cuvette, add the substrate protein to the assay buffer pre-equilibrated at the stress-inducing temperature (e.g., 45°C) or containing a denaturant. Initiate aggregation and record the increase in light scattering over time [32]. - Chaperone Reaction: Repeat the measurement in the presence of the chaperone. Pre-incubate the chaperone with the substrate or add them simultaneously to the stress conditions [32]. - For ATP-Dependent Chaperones: Include an ATP-regenerating system in the reaction buffer to sustain the ATPase cycle [31].

3. Data Analysis: - Initial Rate: Calculate the initial rate of aggregation from the steepest slope of the scattering curve. - Lag Time: Measure the time before a rapid increase in scattering occurs. - Final Extent: Compare the maximum scattering signal achieved in the control versus the chaperone-containing reaction. Effective chaperones will significantly reduce the initial rate, extend the lag time, and decrease the final extent of aggregation [32] [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Chaperone Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimentation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Stalled Ribosome-Nascent Chain Complexes (RNCs) | To capture and study defined intermediates during co-translational folding [25]. | Mapping folding pathways of nascent chains with HDX-MS [25]. |

| ATP-Regenerating System | To maintain constant ATP levels for sustained activity of ATP-dependent chaperones during long assays [31]. | Hsp70/Hsp40 refolding assays; GroEL/GroES encapsulation experiments [31]. |

| Model Aggregation-Prone Substrates | Client proteins used to quantitatively assess chaperone "holdase" activity [32] [34]. | Citrate synthase, insulin, and apoflavodoxin for thermal or chemical denaturation assays [32] [34]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | To generate chaperone mutants for probing structure-function relationships and mechanistic studies [34]. | Creating affinity variants of Spy to study the relationship between binding strength and mechanism [34]. |

| Deuterium Oxide (D₂O) & Quenching Buffers | Essential components for HDX-MS experiments to monitor protein dynamics and folding [25]. | Probing the conformational status and protection of nascent chains on ribosomes [25]. |

Visualization of a Chaperone-Assisted Folding Pathway

The following diagram details the specific pathway of co-translational folding for a model protein like DHFR, as resolved by HDX-MS, highlighting the roles of the ribosome and chaperones.

Practical Refolding Protocols: From Denaturant to Native State

The production of recombinant proteins in bacterial systems like Escherichia coli frequently results in the formation of inclusion bodies (IBs)—protein aggregates with non-native conformations that lack biological activity [22] [35]. While containing relatively pure and intact recombinant proteins, these aggregates require refolding to recover active, correctly folded proteins suitable for research, diagnostics, and therapeutic development [22] [36]. The core challenge of in vitro refolding lies in managing the kinetic competition between first-order folding reactions and second-or higher-order aggregation pathways, the latter being favored at higher protein concentrations [37]. This application note details three fundamental refolding techniques—dilution, dialysis, and on-column refolding—within the context of modern chaperone-assisted research, providing structured protocols and quantitative comparisons to guide researchers in reconstituting biologically active proteins from inclusion bodies.

Core Refolding Principles and the Kinetic Competition

Protein refolding from a denatured state is a self-assembly process driven by intramolecular interactions. However, during refolding, transient folding intermediates expose hydrophobic regions that can interact intermolecularly, leading to irreversible aggregation [38] [35]. This aggregation follows higher-order kinetics than folding, making it particularly dominant at high protein concentrations [35] [37]. The primary goal of any refolding technique is to navigate the protein through this aggregation-prone window while maintaining the protein at the highest possible concentration to maximize the yield of the native fold [35]. The presence of disulfide bonds adds complexity, requiring carefully controlled redox conditions to facilitate correct pair formation [36] [39].

Table 1: Key Performance Indicators of Major Refolding Techniques

| Technique | Typical Recovery Yield | Typical Protein Concentration | Time Requirement | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Dilution | ≤40% [22] | 1–10 mg/mL [22] | 1-2 days [22] | Simplicity of operation | Large volume, low final concentration |

| Dilution with Additives | ≥80% [22] | 1–10 mg/mL [22] | 1-2 days [22] | High refolding yield | Requires additive optimization |

| Dialysis | ≤40% [22] | 1–10 mg/mL [22] | 1-2 days [22] | Constant protein concentration | Slow, aggregation at medium denaturant |

| On-Column Refolding | Varies by protein [36] | Limited by column capacity | Several hours [36] | Reduced aggregation, simple buffer exchange | Requires His-tag, optimization |

| Microfluidic Chip | ≥70% [22] | ≥250 μg/mL [22] | ≥10 min [22] | Rapid mixing, controllable gradient | Specialized equipment needed |

Established Refolding Methodologies

Direct Dilution

Principle

The direct dilution method rapidly reduces the concentration of denaturant and protein by introducing a small volume of denatured protein solution into a large volume of refolding buffer. This instantaneous drop in denaturant concentration initiates refolding, while the simultaneous dilution of the protein minimizes intermolecular collisions that lead to aggregation [22] [35].

Detailed Protocol

- Solubilization: Isolate IBs by centrifugation and wash with a buffer containing Triton X-100 to remove membrane contaminants [35]. Solubilize the pellet in a solubilization buffer (e.g., 6–8 M GuHCl or urea, 50 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) supplemented with a reducing agent (e.g., 10–100 mM DTT or 1% 2-mercaptoethanol) to break disulfide bonds. Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation [40] [35].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the solubilized mixture at 15,000 × g for 20 minutes to remove any residual insoluble material.

- Refolding: Rapidly pipette the clarified supernatant into a vigorously stirred volume of pre-chilled refolding buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). A typical dilution factor is 100-fold, but this requires optimization [22] [35].

- Redox System: For disulfide-bonded proteins, include a redox system in the refolding buffer, such as reduced/oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG). A ratio of 2:1 to 10:1 (GSH:GSSG) is common, with total glutathione concentrations of 1–5 mM [36] [39].

- Incubation: Allow the refolding reaction to proceed for 12–48 hours at 4–10°C without agitation to minimize aggregation.

Workflow Diagram

Dialysis

Principle

Dialysis relies on the gradual removal of denaturants through diffusion across a semi-permeable membrane. The slow change in solvent composition allows the protein to explore its conformational landscape more gradually, potentially bypassing aggregation-prone states that occur at intermediate denaturant concentrations [22]. Step-wise dialysis, which uses a series of buffers with decreasing denaturant concentrations, offers even greater control [22].

Detailed Protocol

- Solubilization: Prepare the denatured protein as described in Section 3.1.2.

- Setup: Load the denatured protein solution into a dialysis membrane with an appropriate molecular weight cutoff.

- Refolding via Dialysis:

- One-Step Dialysis: Dialyze directly against a large volume (e.g., 1000x sample volume) of refolding buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). Change the buffer 2–3 times over 24–48 hours [22].

- Step-Wise Dialysis: For greater control, first dialyze against a buffer containing a medium concentration of denaturant (e.g., 2–4 M urea), then progressively step down to lower concentrations, and finally into a denaturant-free refolding buffer. Equilibrate for 4–8 hours at each step [22] [35].

- Redox Conditions: Include a redox pair like GSH/GSSG in the final dialysis buffer if the protein requires disulfide bond formation.

On-Column Refolding

Principle

On-column refolding, or matrix-assisted refolding, immobilizes the denatured protein on a solid support before initiating refolding. This physical separation of protein molecules prevents intermolecular aggregation during the critical refolding process [40] [36]. Immobilized Metal Ion Affinity Chromatography (IMAC) is commonly used for His-tagged proteins.

Detailed Protocol

- Solubilization and Binding: Solubilize IBs as in 3.1.2. Use a denaturing binding buffer (e.g., 6 M GuHCl, 20 mM imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0). Load the clarified supernatant onto an IMAC column (e.g., Ni-NTA) pre-equilibrated with the same buffer. The denatured protein binds to the resin via its affinity tag [36].

- Wash: Wash the column with 5–10 column volumes (CV) of binding buffer to remove unbound contaminants and residual reducing agents.

- Gradual Denaturant Removal: Apply a linear or step-wise gradient from the denaturing buffer to a native refolding buffer over 5–10 CV. The refolding buffer should lack denaturant and contain components that promote correct folding (e.g., arginine, glycerol, redox systems) [36].

- Final Wash and Elution: After the gradient, wash with an additional 5–10 CV of refolding buffer. Elute the refolded protein with an elution buffer containing high imidazole (e.g., 250–500 mM).

Workflow Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Successful refolding often depends on the use of specific additives that suppress aggregation, stabilize folding intermediates, or facilitate correct disulfide bond formation [22] [40] [36].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Refolding

| Reagent Category | Example Compounds | Primary Function & Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Denaturants | Urea, Guanidine HCl (GdnHCl) | Solubilize IBs by disrupting hydrophobic interactions; at low concentrations, can suppress aggregation [22] [40]. |

| Reducing Agents | Dithiothreitol (DTT), 2-Mercaptoethanol, TCEP | Reduce incorrect disulfide bonds in solubilized IBs to prepare for correct oxidative refolding [22] [35]. |

| Redox Pair Systems | Reduced/Oxidized Glutathione (GSH/GSSG), Cysteine/Cystine | Create a redox shuttle in the refolding buffer to catalyze the formation and isomerization of correct disulfide bonds [36] [39]. |

| Amino Acid Additives | L-Arginine, L-Proline | Suppress protein aggregation by weak association with folding intermediates; arginine is the most widely used [22] [40]. |

| Polyols and Sugars | Glycerol, Sucrose, Trehalose, PEG | Act as excluded solutes (kosmotropes) that stabilize the native protein state by preferential hydration [22] [40]. |

| Detergents & Surfactants | CHAPS, Triton X-100, N-Lauroylsarcosine | Solubilize IBs under mild conditions or shield hydrophobic patches on folding intermediates to prevent aggregation [40] [35]. |

| Artificial Chaperones | Cyclodextrins | First, a detergent (e.g., CTAB) binds to hydrophobic regions to prevent aggregation; then cyclodextrin strips away the detergent to allow controlled refolding [40]. |

Advanced Refolding and Analytical Considerations

Refolding with Chemical Additives and Artificial Chaperones

The strategic use of chemical additives is critical for improving refolding yields. Arginine, in particular, is highly effective at concentrations of 0.4–1.0 M in suppressing aggregation without inhibiting the folding reaction itself [22]. Artificial chaperone systems use a two-step process: first, a detergent like cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) binds to the denatured protein to prevent aggregation; subsequently, a stripping agent like cyclodextrin is added to remove the detergent and allow the protein to refold in a controlled manner [40].

Quantitative Analytics for Refolding States

Monitoring refolding processes is challenging due to low protein concentrations and transient intermediates. A simplified kinetic model describes the dynamics between the folding intermediate (I), native (N), and aggregated (A) states [38]. Analytical techniques like HPLC and enzymatic activity assays are reference standards. High-throughput quantitative methods, such as MALDI-TOF-MS with 18O-labeled internal standards, can be used to optimize refolding conditions for disulfide-bonded proteins by accurately quantifying the formation of native disulfide bonds [39].

Dilution, dialysis, and on-column refolding represent three foundational methodologies for recovering active proteins from inclusion bodies. The choice of method depends on the protein's characteristics, available resources, and the required yield and concentration. The integration of chemical additives, particularly aggregation suppressors like arginine and optimized redox systems, is a powerful strategy to enhance the efficiency of any refolding process. As the field advances, the implementation of quantitative analytics and high-throughput screening will be essential for moving from empirical optimization to knowledge-driven, robust refolding platform strategies.

Within the broader research on chaperone-assisted protein refolding, establishing a baseline spontaneous refolding protocol is fundamental. This protocol details the methodology for recovering active Carbonic Anhydrase B (CAB) from its urea-denatured state without the assistance of folding modulators, providing a critical control for evaluating the efficacy of various chaperone systems [22]. The spontaneous refolding process is driven by the innate thermodynamic principle that a protein's native structure is the most stable under physiological conditions [3]. However, the journey from a denatured, unfolded chain to the correctly folded native state is often hampered by off-pathway events, particularly aggregation, which occurs when exposed hydrophobic surfaces interact irremediably [22] [41]. This protocol aims to minimize such aggregation through controlled denaturant removal, enabling researchers to quantify the baseline yield of active enzyme, against which the performance of artificial or natural chaperones can be measured [42].

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential reagents required for the denaturation and refolding of CAB.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function in Protocol | Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Carbonic Anhydrase B (CAB) | Target protein for refolding studies | Isolated from bovine erythrocytes; >95% purity. |

| Urea | Chemical denaturant | Ultra-pure grade; fresh 8M solution prepared in Buffer A to avoid cyanate formation. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reducing agent | Added to denaturation buffer to reduce and prevent incorrect disulfide bond formation. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | Refolding buffer (Buffer A) | 50 mM, pH 8.5, serves as the physiological-like buffer for refolding [42]. |

| EDTA | Chelating agent | 1 mM in Buffer A; chelates metal ions that may catalyze oxidation. |

Methodology

Denaturation of Native CAB

- Preparation of Denaturation Solution: Prepare a denaturation buffer containing 8 M Urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), and 5 mM DTT.

- Denaturation Process: Add the native CAB protein to the denaturation buffer at a final concentration of 1 mg/mL.

- Incubation: Allow the mixture to incubate at room temperature (25°C) for 2 hours to ensure complete unfolding and reduction.

Spontaneous Refolding via Dilution

- Initiation of Refolding: To initiate refolding, rapidly dilute the denatured protein solution 100-fold into a large volume of pre-chilled Refolding Buffer (Buffer A: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 1 mM EDTA).

- Final Conditions: This dilution reduces the urea concentration to a non-denaturing level (0.08 M) and the protein concentration to 10 μg/mL, a low concentration critical for minimizing intermolecular aggregation [22].

- Refolding Incubation: Allow the refolding reaction to proceed for 12-16 hours (overnight) at 4°C to maximize the recovery of active enzyme.

Activity Assay

- The enzymatic activity of refolded CAB is determined using a standard esterase activity assay with p-nitrophenyl acetate as the substrate.

- The refolding yield is calculated by comparing the activity of the refolded sample to an equivalent amount of native, undenatured CAB.

Expected Results and Data Analysis

Under the optimized conditions described above, the spontaneous refolding of CAB typically achieves a reactivation yield of <10% [42]. The majority of the protein forms aggregates or misfolded species that precipitate out of solution. The following table summarizes the key quantitative parameters and expected outcomes.

Table 2: Summary of Refolding Parameters and Expected Outcomes

| Parameter | Denatured State | Refolding Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Urea Concentration | 8 M | ~0.08 M |

| Protein Concentration | 1 mg/mL | 10 μg/mL |

| Key Additives | 5 mM DTT | None (Spontaneous) |

| Incubation Temperature | 25°C | 4°C |

| Typical Incubation Time | 2 hours | 12-16 hours |

| Expected Yield of Active Protein | 0% | <10% |

The low yield underscores the challenges of spontaneous refolding, where the competition between correct folding and aggregation is often lost [22] [41]. This result highlights the necessity for assisted refolding strategies, such as the use of artificial chaperones, which can capture the unfolded protein and prevent aggregation, thereby increasing the reactivation yield to over 80% [42].

Workflow and Logical Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the critical steps and potential outcomes of the spontaneous refolding protocol, highlighting the decision points and the central role of aggregation.

Comparison with Artificial Chaperone-Assisted Refolding

The stark contrast in efficiency between spontaneous and assisted refolding justifies the research into chaperone systems. The following diagram and table detail the artificial chaperone process for direct comparison.

Table 3: Spontaneous vs. Artificial Chaperone-Assisted Refolding of CAB