Advanced Strategies for Enhancing Protein Solubility and Stability: From Molecular Design to Clinical Application

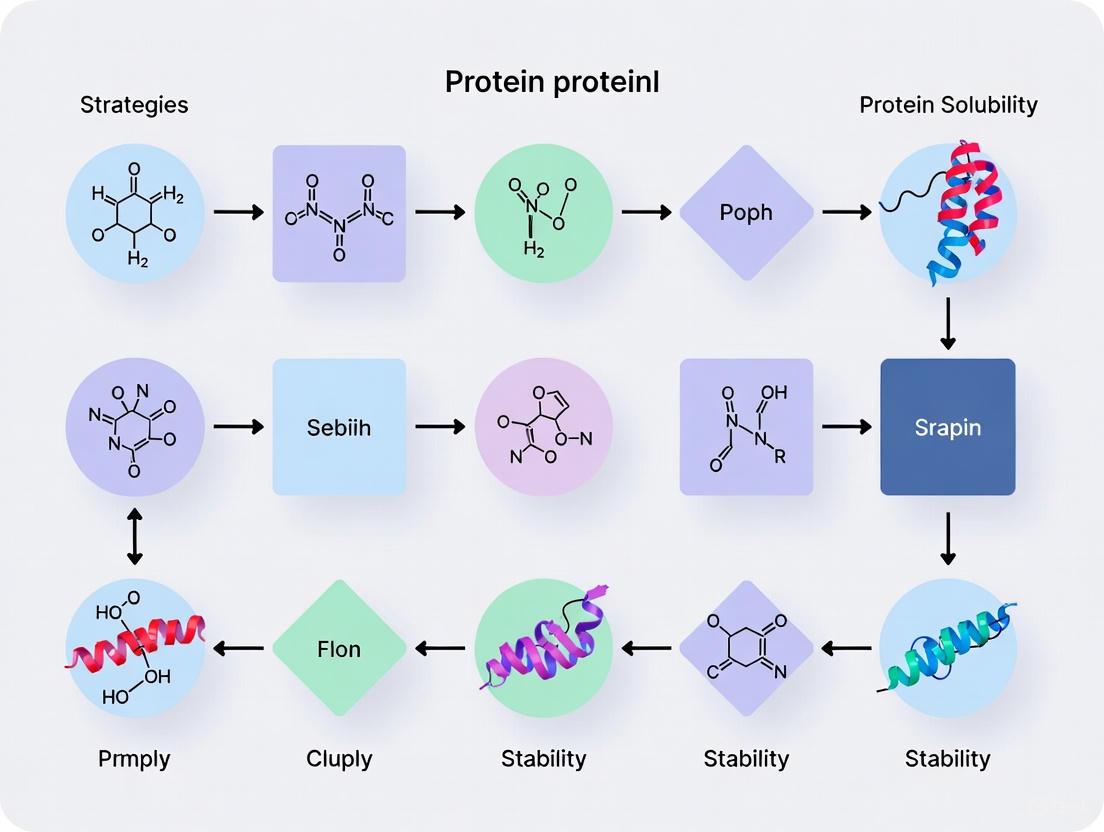

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of contemporary strategies for enhancing protein solubility and stability, critical factors in biotherapeutic development and research applications.

Advanced Strategies for Enhancing Protein Solubility and Stability: From Molecular Design to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of contemporary strategies for enhancing protein solubility and stability, critical factors in biotherapeutic development and research applications. It systematically examines the fundamental causes of protein instability and aggregation, explores molecular engineering techniques including fusion tags and chaperone co-expression, and details computational approaches like AI-driven design for multi-property optimization. The content also covers practical troubleshooting methodologies and comparative validation frameworks to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the most effective stabilization protocols. By integrating foundational science with cutting-edge methodological advances, this resource aims to bridge the gap between protein engineering innovation and practical biopharmaceutical applications.

Understanding Protein Instability: Fundamental Challenges and Mechanisms

The Economic and Scientific Impact of Protein Instability in Biopharmaceutical Development

Protein instability represents a critical bottleneck in biopharmaceutical development, with profound economic and scientific consequences. The global protein stability analysis market, valued at $2.43 billion in 2024, is projected to reach $5.48 billion by 2031, reflecting a robust CAGR of 11.35% [1]. This growth is driven by the increasing demand for biopharmaceuticals—complex protein-based therapeutics that require rigorous stability analysis to ensure their quality, efficacy, and safety [1]. Protein instability manifests as aggregation, misfolding, and precipitation, leading to reduced therapeutic efficacy, potential immunogenicity, and product failure. For researchers and drug development professionals, addressing these challenges is paramount to advancing biological therapeutics from bench to bedside.

The economic burden of protein instability is staggering. Failed bioprocesses and delayed biological development impose huge costs throughout the development pipeline [2]. As the biopharmaceutical industry continues to expand, with monoclonal antibodies alone expected to reach $16 billion in sales, the capacity for manufacturing stable products becomes increasingly challenging [3]. This technical support center provides comprehensive troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help scientists overcome protein instability challenges, framed within the broader context of enhancing protein solubility and stability research.

Economic Impact Analysis

The economic implications of protein instability extend throughout the biopharmaceutical development lifecycle, from early research to commercial manufacturing.

Table 1: Economic Impact of Protein Instability Across Development Stages

| Development Stage | Key Economic Impacts | Magnitude/Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Early R&D | - Failed bioprocesses- Delayed biological development- Cost of stability analysis | $2.43B protein stability analysis market (2024) [1] |

| Process Development | - Cost of reformulation- Additional analytical characterization- Process optimization | 50 kg/year therapeutic protein capacity requires €300-500M investment [3] |

| Commercial Manufacturing | - Plant utilization costs- Yield losses- Capacity constraints | €8M/year per 15,000L bioreactor [3] |

| Clinical & Regulatory | - Late-stage failure costs- Extended development timelines | Process improvements can reduce cost of goods from $1600/g to $260/g [3] |

Table 2: Capacity and Investment Requirements for Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing

| Parameter | Requirement | Economic Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Capacity Reserve | ~50 kg therapeutic protein/year | Requires jump investments of €300-500M every 5-10 years [3] |

| Bioreactor Operating Cost | Each 15,000L bioreactor | €8 million per year in costs [3] |

| Greenfield Plant Investment | 6 × 15,000L bioreactors | €300-500 million including commissioning [3] |

| Process Improvement Impact | 10-fold titer increase + 30% yield improvement | Reduces bioreactors from 31 to 2 for 250kg/year production [3] |

The economic analysis reveals that a continuous strategic capacity reserve of approximately 50 kg of therapeutic protein per year is necessary to sustain business operations, backed by jump investments of €300-500 million every 5-10 years [3]. These investments carry significant risk, as they must be committed before clinical success is guaranteed. The high cost of manufacturing infrastructure—with start-up costs around €100 million for a plant with 6 × 15,000L bioreactors—means that inefficient processes due to protein instability can dramatically increase the cost of goods sold [3]. Process improvements that enhance protein stability can generate substantial economic benefits: a 10-fold increase in titer coupled with a 30% increase in yield can reduce the number of required bioreactors from 31 to 2 for annual production of 250 kg of protein, slashing capital requirements from €1600 million to €100 million and reducing cost of goods from $1600/g to $260/g [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Protein Instability Issues

FAQ 1: How can I improve soluble expression of recombinant proteins in prokaryotic systems?

Challenge: A considerable portion of recombinant proteins fail to attain functional conformations in prokaryotic systems, primarily aggregating as inclusion bodies or undergoing proteolytic degradation [2].

Solutions:

- Molecular chaperone co-expression: Overexpress folding catalysts like GroEL-GroES, DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE, and TF to assist proper folding. Co-expression of GroEL-GroES with recombinant proteins in E. coli can enhance soluble yield by 2-5 fold by preventing aggregation [2].

- Fusion tags: Incorporate solubility-enhancing tags such as MBP, GST, NusA, or SUMO at the N- or C-terminus. These tags act as structural scaffolds, with MBP increasing solubility for over 70% of tested proteins [2].

- Culture condition optimization: Add chemical chaperones like glycerol (1-5%), arginine (0.1-0.5M), or cyclodextrins to the culture medium. Glycerol at 2-5% can enhance thermal stability and reduce aggregation of folding intermediates [2].

- Promoter engineering and codon optimization: Use tunable promoters and optimize codons to match host tRNA abundance, reducing translational errors that cause misfolding [2].

FAQ 2: What strategies can prevent protein aggregation during purification and storage?

Challenge: Proteins aggregate during purification steps or have limited shelf-life due to instability.

Solutions:

- Buffer optimization: Adjust pH to maximize stability, typically away from the isoelectric point. Include excipients like sucrose (0.2-0.5M), glycerol (10-20%), or amino acids (e.g., 0.1-0.5M glycine) to stabilize native structure [4].

- Complexation with ligands: Form protein-polyelectrolyte complexes with polysaccharides like pectin, xanthan gum, or carrageenan through electrostatic interactions to enhance stability [5].

- Control ionic strength: Add salts like sodium chloride (50-150mM) to shield electrostatic interactions, but avoid high concentrations that may cause salting-out [4].

- Site-directed mutagenesis: Replace hydrophobic surface residues with hydrophilic ones (e.g., Lys, Arg, Glu) to reduce aggregation propensity. This requires structural knowledge but can dramatically improve solubility [4].

FAQ 3: How can I rapidly screen formulation conditions for protein stability?

Challenge: Traditional stability testing requires large protein amounts and extended timeframes, slowing development.

Solutions:

- High-throughput stability screening: Utilize instruments like Optim1000 or Optim 2 that can analyze up to 144 samples per day using only 9μL sample volumes (as little as 0.1μg protein) [6].

- Accelerated stability studies: Employ thermal shift assays with dyes like SYPRO Orange to measure melting temperatures (Tm) across different formulations in 96-well format [1].

- Advanced analytical techniques: Implement differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), dynamic light scattering (DLS), and spectroscopy to assess stability under various conditions [1].

- AI-driven prediction tools: Use AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold to predict stability changes from sequence, guiding rational design of stabilising mutations [2].

Systematic Troubleshooting Workflow for Protein Instability Issues

FAQ 4: How do I determine if my protein instability issues stem from expression system limitations?

Challenge: Determining whether observed instability is intrinsic to the protein or results from host system limitations.

Solutions:

- Host system comparison: Express the same construct in alternative systems (E. coli, yeast, insect, mammalian cells). Eukaryotic proteins requiring disulfide bonds or specific chaperones often express better in yeast or mammalian systems [4].

- Glycosylation analysis: Characterize post-translational modifications. Changes in host cell (e.g., CHO to NSO) can alter glycosylation patterns and stability [3].

- Genetic construct verification: Sequence verify constructs and check for unintended mutations. A single amino acid change (e.g., duteplase vs. alteplase) can reduce biological activity by 50% [3].

- Proteostasis assessment: Evaluate whether the host proteostasis network is overwhelmed. High-level expression often exceeds quality control capacity, leading to aggregation [2].

Advanced Methodologies for Enhancing Protein Stability

Complexation Strategies for Stability Enhancement

Complexation with ligands provides a powerful approach to enhance protein stability without genetic modification:

- Protein-Polysaccharide Complexes: Form through non-covalent (electrostatic, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic) or covalent (Maillard reaction) interactions. Pea protein isolate-pectin complexes increase thermal denaturation temperature from 85.12°C to 87.00°C [5].

- Protein-Polyphenol Complexes: Exploit hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions. Polyphenols can prevent aggregation and enhance oxidative stability.

- Chemical Chaperones: Small molecules like glycerol, arginine, and cyclodextrins stabilize proteins by altering solvent properties. Glycerol (1-5%) preferentially excludes from protein surfaces, favoring native state [2].

Table 3: Complexation Strategies for Protein Stabilization

| Complexation Type | Interaction Mechanisms | Stability Enhancement | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Polysaccharide | Electrostatic, H-bonding, hydrophobic, Maillard reaction | Increased thermal denaturation temperature, improved aggregation stability | Beverages, emulsions, nutritional formulations [5] |

| Protein-Polyphenol | H-bonding, hydrophobic interactions | Enhanced oxidative stability, reduced aggregation | Functional foods, therapeutic delivery [5] |

| Chemical Chaperones | Preferential exclusion, solvent modification | Stabilization of folding intermediates, reduced aggregation | Bioprocessing, formulation buffers [2] |

Experimental Protocol: Protein-Polysaccharide Complex Formation

Objective: Enhance protein stability through complexation with polysaccharides.

Materials:

- Water-soluble protein (e.g., whey protein, pea protein)

- Polysaccharide (e.g., pectin, dextran, xanthan gum)

- Buffer components (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.0)

- Dialysis membrane or desalting columns

- Lyophilizer

Methodology:

- Prepare protein and polysaccharide solutions: Dissolve both components in appropriate buffer to 1-5 mg/mL concentration.

- Non-covalent complex formation: Mix protein and polysaccharide solutions at optimal ratio (typically 1:1 to 1:5 protein:polysaccharide weight ratio). Adjust pH to facilitate electrostatic interaction.

- Covalent complex formation (Maillard reaction):

- Mix protein and polysaccharide in phosphate buffer (0.2M, pH 7.0)

- Lyophilize the mixture

- Incubate at 60°C and 65% relative humidity for 1-7 days

- Stop reaction by cooling to 4°C

- Purification: Dialyze against distilled water or use desalting columns to remove unreacted components.

- Lyophilization: Freeze-dry the complexes for long-term storage.

- Characterization: Analyze by SDS-PAGE, size exclusion chromatography, fluorescence spectroscopy, and differential scanning calorimetry.

This protocol typically enhances emulsifying activity index by 1.5-3 fold and increases thermal denaturation temperature by 2-5°C [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Stability Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Stability Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Chaperones | Glycerol, arginine, cyclodextrins, trehalose | Stabilize folding intermediates, reduce aggregation [2] |

| Fusion Tags | MBP, GST, NusA, SUMO, HaloTag7 | Enhance solubility, improve folding, facilitate purification [2] |

| Molecular Chaperones | GroEL-GroES, DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE, TF | Assist proper folding, prevent aggregation [2] |

| Crosslinkers | DSS, BS3, photo-reactive crosslinkers | Stabilize protein complexes, capture transient interactions [7] |

| Stability Assay Kits | Protein Thermal Shift kits | Monitor thermal stability, screen formulation conditions [1] |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktails | Prevent proteolytic degradation during expression/purification [7] |

Technology Spotlight: Advanced Analytical Tools

Innovative technologies are transforming protein stability analysis:

- High-throughput stability analyzers: Instruments like Optim1000 and Optim 2 enable analysis of up to 144 samples per day using only 9μL sample volumes (0.1μg protein), providing fifty-fold time savings compared to conventional methods [6].

- Microfluidic T-mixers: Enable spectroscopic monitoring of protein folding reactions on timescales of 20 milliseconds upwards using milligram sample quantities [6].

- Nanosecond protein heating: T-jump apparatus can increase sample temperature by 25°C in 8 nanoseconds while taking spectroscopic readings, enabling observation of ultrafast folding events [6].

- AI-driven prediction platforms: Integration of AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold with high-throughput screening enables predictive modeling of protein stability, moving from empirical optimization to rational design [2].

Protein Stability Analysis Workflow

Addressing protein instability in biopharmaceutical development requires an integrated approach combining empirical optimization with rational design. The economic impact of instability—from failed bioprocesses to massive capital investments—demands rigorous stability assessment throughout development. By implementing the troubleshooting strategies, experimental protocols, and advanced methodologies outlined in this technical support center, researchers can significantly enhance protein solubility and stability.

The future of protein stability research lies in the convergence of AI-driven prediction, high-throughput experimentation, and mechanistic understanding of folding pathways. As the biopharmaceutical landscape evolves toward more complex therapeutics, the strategies discussed here will play an increasingly vital role in ensuring the successful development of stable, effective protein-based medicines.

For researchers focused on enhancing protein solubility and stability, a deep understanding of protein degradation pathways is not merely academic—it is a practical necessity. The same mechanisms that maintain cellular homeostasis, such as proteasomal and lysosomal proteolysis, can be harnessed or counteracted to improve protein yield, functionality, and shelf-life in industrial and therapeutic applications [8] [9]. Conversely, uncontrolled aggregation and denaturation are major culprits behind lost research materials, inconsistent experimental results, and failed drug formulations. This guide details the key mechanisms of protein degradation and provides actionable troubleshooting advice to address common challenges encountered in the lab.

FAQ: Core Degradation Concepts for Experimental Design

1. What are the two primary pathways for protein degradation in cells, and which should I consider for my solubility research?

Eukaryotic cells primarily degrade proteins via the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) and Lysosomal Proteolysis [9] [10]. The choice between these pathways has significant implications for research.

- Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS): This is the main pathway for degrading short-lived intracellular proteins and soluble misfolded proteins [8] [11]. It is a highly specific, ATP-dependent process that involves tagging target proteins with a polyubiquitin chain (via E1, E2, and E3 enzymes) for recognition and degradation by the 26S proteasome complex [10] [12]. If your protein of interest is a regulatory cytosolic or nuclear protein, it is likely handled by the UPS.

- Lysosomal Proteolysis: This pathway degrades long-lived proteins, extracellular proteins, cell-surface receptors, and large protein aggregates [8] [10]. It involves engulfing cargo via endocytosis, phagocytosis, or autophagy, followed by delivery to the acidic lysosome for enzymatic breakdown [9]. If you are working with protein aggregates or studying clearance of misfolded proteins, this pathway is central.

The following diagram illustrates the core components and flow of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System:

2. How do protein aggregation and denaturation relate to these degradation pathways?

- Denaturation is the process where a protein loses its native three-dimensional structure, leading to loss of function [13]. It can be a reversible first step or lead to irreversible damage.

- Aggregation occurs when denatured or misfolded proteins self-associate into insoluble complexes [12]. These aggregates are often too large for the proteasome and are primarily targeted for degradation via autophagy, a form of lysosomal proteolysis [8] [11].

In neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, the accumulation of protein aggregates indicates an overload or impairment of these degradation systems [12]. In a lab setting, inducing controlled denaturation is key to analyzing unfolding intermediates, while preventing it is crucial for protein storage and function.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Low Protein Solubility and Unwanted Aggregation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Protein is at or near its isoelectric point (pI), leading to loss of electrostatic repulsion. Solution: Adjust the pH of your buffer away from the protein's pI.

- Cause: Harsh environmental conditions (e.g., high temperature, ionic strength). Solution: Optimize buffer conditions. Include stabilizing agents like polyols (e.g., trehalose, glycerol) or use heavy water (D₂O), which can strengthen stabilizing hydrogen bonds [13].

- Cause: Inherent hydrophobicity or poor conformational stability. Solution: Utilize complexation strategies. Formulating water-soluble proteins with ligands like polysaccharides (e.g., pectin, dextran) via covalent (Maillard reaction) or non-covalent (electrostatic, hydrophobic) interactions can significantly improve solubility and colloidal stability by increasing steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion [14].

Problem 2: Loss of Protein Function Due to Instability

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Protein unfolding/denaturation during storage or processing. Solution: Implement physical processing techniques. High-Pressure Homogenization (HPH) has been shown to modify protein structure, decrease particle size, and enhance solubility and functional properties of plant protein suspensions like lentil and pea protein isolates [15].

- Cause: Repetitive freeze-thaw cycles. Solution: Aliquot proteins into single-use portions to avoid repeated freezing and thawing.

- Cause: Oxidative stress or chemical degradation. Solution: Store proteins with reducing agents (e.g., DTT) and protease inhibitor cocktails. For long-term stability, consider engineered covalent modifications like "capping" with polyethylene glycol (PEG) to increase stability and prevent immune responses [13].

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol 1: Assessing Thermal Stability by Electrophoresis

Thermal shift assays can be adapted to gel electrophoresis to visualize unfolding transitions and trap intermediates [13].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare identical protein samples in your desired buffer.

- Heat Treatment: Incubate samples at a range of temperatures (e.g., 25°C to 95°C) for a fixed time (e.g., 10 minutes).

- Cooling: Cool samples on ice to quench the reaction.

- Analysis:

- Native PAGE: Analyze samples to monitor the loss of native structure and the appearance of unfolding intermediates.

- SDS-PAGE: Analyze samples (under non-reducing conditions if applicable) to check for irreversible aggregation or cleavage that occurred upon heating.

Protocol 2: Enhancing Solubility via Protein-Polysaccharide Complexation

This protocol is based on strategies reviewed for enhancing water-soluble protein functionality [14].

- Preparation: Dissolve the water-soluble protein and a chosen polysaccharide (e.g., high methoxyl pectin, dextran) separately in buffer. The pH should be adjusted to favor electrostatic interaction if using non-covalent complexation.

- Complexation:

- For Non-covalent Complexes: Mix the protein and polysaccharide solutions under gentle stirring. The complexes form spontaneously driven by electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions.

- For Covalent Complexes (Conjugates): For a Maillard reaction, mix the protein and polysaccharide in a dry state at a specific ratio and incubate under controlled temperature and humidity (e.g., 60°C, 79% relative humidity) for a set period.

- Purification: Dialyze or centrifugally filter the mixture to remove unreacted components.

- Characterization: Use techniques like size-exclusion chromatography, dynamic light scattering, and SDS-PAGE to confirm complex formation and determine changes in particle size and solubility.

Quantitative Data on Denaturation Agents

The following table summarizes common agents used to denature proteins in controlled experiments and their typical mechanisms [13].

| Denaturation Agent | Typical Working Concentration | Primary Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Urea | 4 - 8 M | Disrupts hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, leading to protein unfolding. |

| Guanidinium HCl | 4 - 6 M | Similar to urea; competes for hydrogen bonds and charges buried amino acids. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | 0.1 - 1% | Binds to the protein backbone, imparting negative charge and disrupting hydrophobic interactions. |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) | 1 - 10 mM | Reduces disulfide bonds, disrupting the covalent structure of the protein. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table lists essential reagents used in protein stability and degradation research, as cited in the literature.

| Research Reagent | Function / Application | Key Context from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) | Bifunctional molecules that recruit an E3 ligase to a protein of interest, inducing its ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome [8] [11]. | Used as a novel therapeutic modality and research tool to degrade specific intracellular proteins [8]. |

| Molecular Glues (e.g., Thalidomide analogs) | Small molecules that induce proximity between an E3 ligase and a target protein, leading to its degradation [8]. | A key modality in targeted protein degradation; includes clinically approved agents like lenalidomide [8] [16]. |

| Polyols (e.g., Trehalose, Glycerol) | Stabilizing cosolvents that can substitute for water, strengthening hydrogen bonds and increasing protein stability under stress [13]. | Used to prevent denaturation during storage or freezing and to increase the free energy required for unfolding [13]. |

| E1/E2/E3 Enzymes | The enzymatic cascade (Activating, Conjugating, and Ligase enzymes) that mediates the ubiquitination of protein substrates [10] [12]. | Essential components of the UPS; the specificity of E3 ligases makes them attractive drug targets [8] [12]. |

| Hydrophobic Tags (HyT) | A targeted degradation strategy that mimics a misfolded protein, recruiting chaperones and the UPS for degradation [8]. | An emerging alternative to PROTACs for inducing targeted protein degradation [8]. |

Pathway Visualization: Lysosomal Proteolysis

The lysosomal pathway is critical for degrading a wide array of materials, including extracellular proteins and large aggregates. The diagram below outlines the major routes into this pathway.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

My protein is not expressing at all. What could be wrong?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Problem with the DNA Construct: The expression cassette might contain errors.

- Solution: Check your construct by sequencing the entire expression cassette to ensure there are no unintended stop codons or mutations [17].

- Problem with the Promoter/Translation Initiation: Secondary structures in the mRNA can prevent efficient translation initiation [18].

- Problem with Codon Usage: The gene may contain codons that are rare in your expression host, causing translation to stall [19].

- Toxic Protein: Even low levels of "leaky" basal expression can prevent cell growth if the protein is toxic [18] [19].

My protein is expressing but is insoluble (forming inclusion bodies). How can I improve solubility?

This is a classic symptom of an evolutionary mismatch, where the host's folding machinery is overwhelmed or incompatible with the heterologous protein [2].

- Slow Down Expression: Rapid expression can overwhelm the host's chaperone systems.

- Augment the Folding Machinery: Provide the host with additional helpers to fold the foreign protein.

- Use a Solubility-Enhancing Fusion Tag: Fuse your protein to a highly soluble partner.

- Modify the Protein Sequence Intrinsically: Re-engineer the protein to be more compatible with the host.

How can I ensure proper disulfide bond formation in my recombinant protein?

Disulfide bond formation is often inefficient in the reducing cytoplasm of standard E. coli strains, another form of evolutionary mismatch in redox potential.

- Solution 1: Target the Protein to the Periplasm. Use a vector with a signal sequence (e.g., pelB, ompA) to export the protein to the oxidative periplasm, where the Dsb enzyme family catalyzes disulfide bond formation [18].

- Solution 2: Use Engineered Cytoplasmic Strains. Specialized strains like SHuffle are engineered to have an oxidizing cytoplasm and also express disulfide bond isomerase (DsbC) in the cytoplasm, allowing for correct disulfide bond formation in the cytosolic compartment [18].

What are the latest technological advances for solving these problems?

The field is moving towards more rational and high-throughput strategies.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning: Tools like AlphaFold2 can predict protein structures to identify problematic regions [2]. Support Vector Regression (SVR) models can predict solubility from sequence and guide the in silico optimization of protein sequences or the design of short peptide tags before any wet-lab work is done [20].

- Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction: Computational resurrection of ancestral protein sequences can sometimes yield more stable and soluble variants that are easier to express in modern hosts [2].

- High-Throughput Screening: Automated platforms allow for the simultaneous testing of hundreds of expression conditions, chaperone combinations, and fusion tags to rapidly identify the optimal setup for a difficult protein [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Small-Scale Expression Test and Solubility Check

This is a fundamental first step to diagnose expression and solubility issues [17] [21].

Materials:

- LB medium with appropriate antibiotic

- IPTG (or other inducer) stock solution

- Shaking incubator

- Refrigerated centrifuge

- Lysis buffer (e.g., BugBuster reagent)

- SDS-PAGE equipment

Method:

- Inoculate a small culture (5-10 mL) and grow to mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6).

- Take a 1 mL pre-induction sample. Pellet the cells and store at -20°C.

- Add the optimal concentration of IPTG (e.g., 0.1 mM) to induce expression.

- Induce for 3-4 hours, then take a 1 mL post-induction sample.

- Pellet the cells from the post-induction sample. Resuspend in lysis buffer.

- Lyse the cells by incubation on a shaking platform for 20 minutes.

- Centrifuge the lysate at high speed (e.g., 13,000 rpm) for 10 minutes to separate soluble (supernatant) and insoluble (pellet) fractions.

- Resuspend the pellet in the same volume of buffer as the supernatant.

- Analyze the pre-induction sample, total post-induction lysate, soluble fraction, and insoluble fraction by SDS-PAGE to assess expression levels and solubility.

Protocol 2: Co-expression with Molecular Chaperones

This protocol directly addresses the folding machinery mismatch [2].

Materials:

- Chaperone plasmid set (e.g., Takara's) or individual chaperone plasmids (e.g., for GroEL/GroES, DnaK/DnaJ)

- Two compatible antibiotics

- Culture medium

Method:

- Co-transform your target protein expression vector and a chaperone plasmid into your expression host. The chaperone plasmid should have a compatible origin of replication and a different antibiotic resistance marker.

- Grow a culture from a single colony in medium containing both antibiotics.

- Induce the expression of the chaperones first, typically by adding L-arabinose or elevating the temperature, according to the specific chaperone system's instructions.

- After a period of chaperone induction, induce the expression of your target protein with IPTG.

- Continue with growth, cell harvest, and lysis as in Protocol 1 to check for improvements in soluble yield.

Table 1: Effectiveness of Common Solubility-Enhancing Fusion Tags

| Fusion Tag | Size (kDa) | Key Mechanism | Key Advantage | Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP) | ~42.5 | Acts as a folding nucleus, improves solubility [18] | Allows purification on amylose resin; often retains activity of fusion partner [18] | Large size may interfere with structure/function studies; requires cleavage |

| Thioredoxin (Trx) | ~11.7 | High intrinsic solubility, can facilitate disulfide bond formation in cytoplasm [2] | Small tag, less likely to interfere with function | May not be as effective as MBP for some proteins |

| N-utilizing substance A (NusA) | ~54.8 | Significantly enhances solubility of fusion partners [2] | One of the most effective solubility tags available | Very large size |

| Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO) | ~11 | Acts as a chaperone; recognized by highly specific proteases for cleavage [2] | Enables clean, scarless removal after purification | Requires specific protease (Ulp1) for cleavage |

| Hexa-Lysine Peptide Tag | ~0.8 | Increases net charge, enhancing solubility via electrostatic repulsion [2] [20] | Very small, minimal structural impact | May not be sufficient for severely aggregating proteins |

Table 2: Common Chemical Chaperones and Additives to Enhance Solubility

| Chemical Chaperone/Additive | Typical Concentration | Proposed Mechanism of Action | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerol | 0.5 - 2 M | Preferential exclusion from protein surface, stabilizing native state [2] | Increased yield and activity of human phenylalanine hydroxylase in E. coli [2] |

| L-Arginine | 0.1 - 0.5 M | Suppresses protein aggregation; commonly used in refolding buffers [2] | Used to suppress aggregation during dilution refolding processes |

| Betaine / Proline | 0.5 - 2 M | Acts as an osmolyte, stabilizing proteins under stress conditions [2] | Enhanced soluble expression of pullulanase in E. coli [2] |

| Cyclodextrins | 0.5 - 2% (w/v) | May sequester hydrophobic molecules or protein patches, preventing aggregation [2] | Improved secretion of α-cyclodextrin glucosyltransferase [2] |

| Ethanol | 1-5% (v/v) | Induces heat-shock response, upregulating endogenous chaperones [2] [17] | Increased soluble yield of recombinant proteins when added pre-induction [2] |

Visual Guides

Diagram 1: The Evolutionary Mismatch Crisis in Protein Folding

This diagram illustrates the core concept of evolutionary mismatch in heterologous protein expression.

Diagram 2: Strategic Framework to Overcome Folding Mismatch

This workflow outlines the decision process for selecting the right strategy to enhance soluble protein expression.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Troubleshooting Expression

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| BL21(DE3) & Derivatives | Standard E. coli protein expression host. | General-purpose protein expression [18]. |

| Rosetta / Codon Plus Strains | Supply rare tRNAs for codons not commonly used in E. coli. | Expressing genes with codons for Arg, Ile, Gly, etc., that are rare in E. coli [17] [19]. |

| SHuffle T7 Express | Engineered for disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm. | Production of proteins requiring disulfide bonds for stability/activity [18]. |

| pLysS / pLysE Strains | Express T7 lysozyme to inhibit basal T7 RNA polymerase activity. | Reducing basal ("leaky") expression of toxic proteins in T7 systems [18]. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Sets | Allow for co-expression of specific molecular chaperone systems. | Enhancing proper folding of complex eukaryotic proteins [2] [17]. |

| pMAL Vectors | Vectors for creating MBP fusion proteins. | Dramatically improving solubility of insoluble target proteins [18]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How does macromolecular crowding specifically affect the folding kinetics of different protein structural motifs?

Answer: Macromolecular crowding's effect is not uniform and depends critically on the protein's size and structural motif. Contrary to the common assumption that crowding always increases folding rates due to the excluded volume effect, studies on small folding motifs reveal a more complex picture.

For Small Helical Peptides: Crowding agents like Dextran 70 and Ficoll 70 (at 200 g/L) induce no appreciable changes in the folding-unfolding kinetics of a 34-residue α-helix (L9:41-74) and only a moderate decrease in the relaxation rate of a 34-residue cross-linked helix-turn-helix motif (Z34C-m1) [22]. This is surprising given that helix-coil transition kinetics are known to depend on viscosity.

For Small Beta-Hairpins: In contrast, the same crowding conditions lead to an appreciable decrease in the folding rate of a 16-residue β-hairpin (trpzip4-m1) [22]. This indicates that for very small proteins, factors beyond excluded volume, such as increased frictional drag and transient, non-specific interactions with the crowders, can dominate and slow down the folding process.

Troubleshooting Guide: Unexpected Folding Kinetics in Crowded Environments

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No change or a decrease in folding rate with crowders. | The protein is too small; dynamic friction and transient interactions outweigh the stabilizing excluded volume effect. | Use a larger protein domain (>50 residues) where the excluded volume effect is more dominant [22]. |

| Inconsistent results between different crowding agents. | The physical nature (e.g., flexible coil vs. rigid sphere) of the crowding agent differentially affects the reaction. | Characterize the crowders (e.g., size, flexibility) and use multiple types (e.g., Ficoll 70, Dextran 70) to isolate the effect [22]. |

| Increased protein aggregation in crowded solutions. | Crowding can enhance undesirable intermolecular interactions. | Optimize solution conditions (pH, ionic strength) or use stabilizing ligands to counteract aggregation [14]. |

FAQ 2: Beyond excluded volume, what other mechanisms does molecular crowding introduce that can alter protein oxidation?

Answer: Macromolecular crowding significantly modulates biochemical reaction rates, including protein oxidation, by altering diffusion and reaction pathways. Research shows that crowding agents like dextran can enhance the rate and extent of oxidation for specific amino acids.

Enhanced Oxidation of Tryptophan: The oxidation rate of free Tryptophan (Trp) by peroxyl radicals doubles in the presence of dextran (60 mg/mL). For peptide-incorporated Trp, crowding also increases the extent of consumption and can induce short-chain reactions where radicals generated from Trp go on to oxidize other targets [23].

Specificity of the Effect: Under the same conditions, the oxidation of Tyrosine (Tyr) remains unaffected by crowding [23]. This highlights the residue-specific nature of the phenomenon.

Proposed Mechanism: The confined environment reduces the volume available for reactive species, which can modulate chain termination reactions in radical-driven oxidation, thereby increasing the propagation of damage [23].

Troubleshooting Guide: Managing Protein Oxidation in Crowded Assays

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Higher-than-expected oxidation in crowded in vitro experiments. | Crowding enhances radical propagation, particularly for Trp residues. | Include specific radical scavengers (e.g., antioxidants) in your crowded buffer system [23]. |

| Variable oxidation results between different proteins. | The effect of crowding is dependent on protein structure and solvent exposure of oxidizable residues. | Map oxidizable residues (Trp, Tyr) in your protein structure and monitor their status (e.g., via LC-MS) after experiments [23]. |

FAQ 3: How can I leverage ligand complexation to overcome pH and stability limitations of water-soluble proteins?

Answer: Complexation with various ligands is a established strategy to enhance protein stability and functionality, particularly against aggregation near their isoelectric point (pI) or under harsh environmental conditions [14].

Mechanisms of Stabilization:

- Polysaccharide Complexes: Forming complexes with polysaccharides (e.g., pectin, dextran) via non-covalent (electrostatic, hydrogen bonding) or covalent (Maillard reaction) interactions increases steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion. This prevents aggregation at pH values near the protein's pI and enhances thermal stability [14].

- Molecular Crowding in Complexes: In covalently linked protein-poly saccharide conjugates, a "molecular crowding effect" is proposed to explain the avoidance of protein denaturation under thermal stress [14].

Enhanced Functionality: Ligand complexation can induce conformational changes that expose hydrophobic groups, thereby improving emulsifying properties. The grafted polysaccharide chains also strengthen electrostatic repulsion between droplets, enhancing emulsion stability [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Optimizing Protein-Ligand Complexation

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Protein still aggregates near its pI after complexation. | Insufficient steric or electrostatic shielding by the ligand. | Use a higher ratio of ligand to protein, or switch to a more highly charged polysaccharide (e.g., pectin) [14]. |

| Poor functional enhancement (e.g., emulsification). | The complex may be too hydrophilic, preventing effective interface adsorption. | Try ligands that impart amphiphilicity or use conjugation methods that partially unfold the protein to expose hydrophobic patches [14]. |

| Inconsistent batch-to-batch results. | Uncontrolled reaction conditions for covalent conjugation. | Strictly control parameters like temperature, time, and pH during the Maillard reaction or other conjugation processes [14]. |

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from research on the effects of macromolecular crowding.

Table 1: Quantifying the Impact of Macromolecular Crowding (200 g/L) on Protein Folding Kinetics and Stability [22]

| Protein / Peptide | Structure | Crowding Agent | Effect on Thermal Stability (Tm) | Effect on Folding Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L9:41-74 | 34-residue α-helix | Dextran 70 | No appreciable change | No change (Relaxation time: 1.4 ± 0.2 μs vs 1.17 ± 0.15 μs in buffer) |

| Ficoll 70 | No appreciable change | No change (Relaxation time: 1.5 ± 0.2 μs vs 1.17 ± 0.15 μs in buffer) | ||

| Z34C-m1 | 34-residue HTH | Dextran 70 | Slight increase (+2-3°C) | Moderate decrease in relaxation rate |

| Ficoll 70 | Slight increase (+2-3°C) | Moderate decrease in relaxation rate | ||

| trpzip4-m1 | 16-residue β-hairpin | Dextran 70 | Data Not Specified | Appreciable decrease in folding rate |

| Ficoll 70 | Increased | Appreciable decrease in folding rate |

Table 2: Effect of Crowding (60 mg/mL Dextran) on Protein Oxidation Kinetics [23]

| Oxidizable Target | Reaction | Impact of Crowding |

|---|---|---|

| Free Tryptophan | Oxidation by AAPH-derived peroxyl radicals | Rate increased from 15.0 ± 2.1 to 30.5 ± 3.4 μM min⁻¹ |

| Peptide-incorporated Tryptophan | Oxidation by AAPH-derived peroxyl radicals | Significant increase in rate and extent of consumption (up to 2-fold); induced short-chain reactions |

| Tyrosine | Oxidation by AAPH-derived peroxyl radicals | No significant effect detected |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Folding Kinetics and Stability in Crowded Environments via T-Jump and CD Spectroscopy

Methodology: This protocol uses Laser-Induced Temperature-Jump (T-Jump) infrared spectroscopy to study folding-unfolding kinetics and Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to assess thermodynamic stability [22].

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare the peptide/protein in the desired buffer (e.g., 20 mM phosphate buffer in D₂O, pD 7).

- For crowded conditions, dissolve the crowding agent (e.g., Dextran 70 or Ficoll 70) into the buffer at the target concentration (e.g., 200 g/L). Ensure the polymer is fully dissolved and the solution is homogeneous.

- Incubate the protein sample in the crowded buffer prior to measurement.

Circular Dichroism (CD) for Thermodynamics:

- Acquire far-UV CD spectra (e.g., 190-250 nm) at a low temperature (e.g., 4°C) to confirm the native folded structure.

- Perform thermal denaturation experiments by monitoring the change in CD signal at a characteristic wavelength (e.g., 222 nm for helices) as a function of temperature.

- Fit the resulting melting curve to a two-state model to extract the thermal melting temperature (Tₘ) and thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS).

T-Jump Relaxation Kinetics:

- Use a laser to rapidly increase the temperature of the sample and perturb the folding equilibrium.

- Monitor the relaxation of the system back to equilibrium using an infrared probe, typically at the amide I' band.

- Fit the resulting relaxation kinetics. For simple systems, this may be a single-exponential process. The resolved slow phase corresponds to the conformational folding-unfolding dynamics.

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Impact of Crowding on Protein Oxidation

Methodology: This protocol measures the rate and extent of amino acid oxidation under crowded conditions [23].

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare solutions of the target (free amino acid, peptide, or protein) in an appropriate buffer.

- For the test condition, include a crowding agent like dextran at a physiologically relevant concentration (e.g., 60 mg/mL).

- Initiate oxidation by adding a radical generator, such as AAPH (2,2'-Azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride).

Kinetic Analysis:

- Monitor the consumption of the oxidizable target (e.g., Tryptophan) over time. This can be done via spectrophotometry or chromatography (e.g., HPLC).

- Calculate the rate of oxidation (e.g., μM min⁻¹) for the initial phase of the reaction from the slope of the consumption curve.

Endpoint Analysis:

- After a fixed time, quantify the total extent of oxidation by measuring the remaining unoxidized target.

- Use techniques like SDS-PAGE and LC-MS to analyze higher-order products, such as protein oligomers or cross-linked species, which can be enhanced by crowding.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Protein Folding Energy Landscape Under Crowding

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Crowding Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Physicochemical Barriers to Folding

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll 70 | A compact, highly branched, spherical crowding agent. Used to simulate the excluded volume effects of the cellular environment. | Semi-rigid sphere (Rh ~55 Å). Less likely to form viscous networks compared to linear polymers [22]. |

| Dextran 70 | A flexible, linear polymer used as a crowding agent. | Behaves as a quasi-random coil (Rh ~63 Å). Solutions can have higher microviscosity, potentially influencing frictional drag [22]. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrophotometer | Measures protein secondary structure and monitors thermal denaturation to determine thermodynamic stability (Tₘ). | Essential for confirming that the crowding agent itself does not alter the native fold of the protein under study [22]. |

| Laser T-Jump with IR Detection | Perturbs the folding equilibrium to directly measure the relaxation kinetics of folding and unfolding events on microsecond timescales. | Key for distinguishing between thermodynamic stability (from CD) and kinetic rates of folding [22]. |

| AAPH (Radical Generator) | A chemical initiator that generates peroxyl radicals at a constant rate, used to study protein oxidation under controlled conditions. | Allows for the kinetic analysis of oxidation rates and the probing of chain reaction propagation [23]. |

| Polysaccharides (Pectin, Dextran) | Ligands used to form complexes with proteins to enhance their aggregation, thermal, and pH stability. | Can be used in non-covalent complexes (electrostatic) or covalent conjugates (Maillard reaction) [14]. |

Proteins are fundamental biomolecules for biological research and therapeutic development, yet they are inherently vulnerable to a range of structural instabilities that directly compromise their function. These instabilities—including unfolding, aggregation, and precipitation—present major obstacles in experimental workflows and drug development pipelines. This technical support center operates within a strategic thesis focused on enhancing protein solubility and stability research. It provides targeted troubleshooting guides to help researchers diagnose the root causes of functional deficits—such as loss of activity, poor yields, or inconsistent results—by connecting them to underlying structural vulnerabilities. By adopting this analytical framework, scientists can move beyond trial-and-error approaches to implement rational, effective interventions that rescue protein function and ensure experimental reproducibility.

Troubleshooting Guides: From Problem to Solution

Guide 1: Addressing Low Protein Solubility

Problem: Your purified protein precipitates from solution during storage or handling, leading to inconsistent experimental results and low yields.

Step 1: Diagnose the Cause

- Test: Centrifuge a small sample and measure protein concentration in the supernatant before and after. A significant drop indicates precipitation.

- Analyze: Check buffer conditions (pH, ionic strength). Precipitation often occurs near the protein's isoelectric point or at high salt concentrations.

Step 2: Immediate Interventions

- Modify Buffer Conditions:

- Adjust pH: Move away from the theoretical pI (by ±1 pH unit). Use buffers between pH 7-9 for many proteins.

- Increase ionic strength: Add 50-150 mM NaCl to shield electrostatic attractions.

- Add Stabilizing Agents: Introduce low molecular weight additives to the storage buffer [24].

- Reducing Agents: Dithiothreitol (DTT, 1-5 mM) or β-mercaptoethanol (5-10 mM) to prevent disulfide-mediated aggregation.

- Osmolytes: Glycerol (5-20%) or ethylene glycol to enhance hydration and stability.

- Modify Buffer Conditions:

Step 3: Long-Term Strategies

- Consider Chemical Modification: For persistent issues, explore protein engineering. Deamidation converts asparagine and glutamine residues to aspartic and glutamic acids, increasing charge density and electrostatic repulsion to significantly enhance solubility and emulsification properties [25].

Guide 2: Managing Protein Aggregation

Problem: Your protein forms soluble oligomers or insoluble aggregates, reducing functional protein concentration and potentially causing immunogenicity in therapeutic contexts.

Step 1: Identify Aggregate Type

- Technique: Use Negative Stain Electron Microscopy as a qualitative assay to visualize aggregates directly in your sample [26].

- Protocol Summary: Apply protein sample to a glow-discharged carbon-coated grid, stain with uranyl formate, and image. Aggregates appear as large, irregular clusters compared to monodisperse particles.

Step 2: Disrupt Existing Aggregates

- Mild Detergents: Add non-denaturing detergents (e.g., 0.01-0.1% Triton X-100 or Tween-20).

- Chaotropic Agents: Use low concentrations of urea (1-2 M) or guanidine HCl, but verify functional recovery after removal.

Step 3: Prevent Future Aggregation

- Optimize Storage: Store at high concentration (>1 mg/mL) to discourage dissociation/association cycles.

- Control Temperature: Use constant 4°C storage or flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen for long-term storage. Critical: Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles by aliquoting [24].

Guide 3: Recovering Lost Binding Activity

Problem: Your protein appears stable and soluble but fails to bind its interaction partner or substrate in functional assays.

Step 1: Verify Structural Integrity

- Circular Dichroism: Compare the spectrum to a positive control to check secondary structure.

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Measure melting temperature (Tₘ) shifts. A decreased Tₘ suggests global destabilization.

Step 2: Check for Localized Instability

- Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange-Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS): This technique can reveal increased flexibility or destabilization in specific regions, such as binding interfaces, that may not affect global stability [27].

Step 3: Strategic Stabilization

- Targeted Mutations: If the binding interface is identified and not critical for function, introduce destabilizing mutations in the unbound state. This strategy increases the free energy of the unbound protein without significantly affecting the bound complex, thereby enhancing binding affinity through thermodynamic coupling [27].

- Add Ligands: Include specific substrates or cofactors during storage to stabilize the active conformation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My protein is stable at 4°C for a week but aggregates during long-term storage. What are my best storage options?

A: For long-term storage, lyophilization (freeze-drying) is highly effective when combined with stabilizing cryoprotectants like sucrose or trehalose [24]. For solution storage, aliquot your protein, flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C. Always include 10-20% glycerol as a cryoprotectant for frozen storage, and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles by using single-use aliquots.

Q2: I've identified a potential stabilizing mutation using computational tools, but it made my protein less soluble. Why did this happen?

A: This is a common limitation of current computational tools. Many stability prediction algorithms favor mutations that increase hydrophobicity to gain stability, often at the expense of solubility [28]. When selecting mutations, particularly for surface-exposed residues, prioritize those that maintain or introduce hydrophilic character. Using a meta-predictor that combines multiple tools can improve reliability, but always consider solubility implications in your design strategy.

Q3: What quick methods can I use to check my protein's stability and homogeneity before starting complex experiments?

A: Two rapid quality control assessments are recommended:

- Negative Stain EM: Provides a direct visual assessment of sample homogeneity, complex formation, and the presence of large aggregates within minutes [26].

- Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (Thermal Shift Assay): Measures thermal denaturation curves using a fluorescent dye and real-time PCR instrument, providing a stability profile in under one hour.

Q4: Are there specific chemical modifications that can improve both stability and solubility?

A: Yes, glycosylation is particularly effective. By covalently attaching hydrophilic carbohydrate groups to proteins, glycosylation significantly alters hydrophilicity and can enhance thermal stability, water retention, and mechanical strength of protein gels [25]. Phosphorylation is another valuable technique that introduces negatively charged phosphate groups, increasing electrostatic repulsion and improving solubility and dispersibility [25].

Quantitative Data for Experimental Planning

Table 1: Computational Tools for Predicting Mutation Effects on Stability

The following table summarizes key performance metrics of computational tools for predicting changes in protein stability (ΔΔG) upon amino acid substitution, based on validation against ~600 experimental mutations [28].

| Tool | Underlying Methodology | Correlation Coefficient (R) | Precision (%) | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-predictor | Combined 11 tools | 0.73 | 63 | Most reliable overall approach; mitigates individual tool weaknesses |

| PoPMuSiC | Statistical potentials | 0.68 | 59 | Performs well on surface residues |

| FoldX | Empirical force field | 0.54 | 52 | Good for hydrophobic core mutations |

| EGAD | Physical force fields | 0.52 | 50 | Accurate for buried residues |

| Rosetta-ddG | Empirical/Physical hybrid | 0.54 | 46 | Requires structural refinement steps |

| I-Mutant3 | Machine learning | 0.51 | 41 | Sequence-based prediction available |

Data sourced from [28]. The meta-predictor combines multiple tools weighted by performance, available at: meieringlab.uwaterloo.ca/stabilitypredict/

Table 2: Protein Stabilization Methods and Their Applications

This table compares different protein stabilization approaches, their mechanisms, and optimal use cases to guide method selection.

| Method | Mechanism | Key Parameters | Optimal Applications | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deamidation [25] | Converts Asn/Gln to Asp/Glu; increases charge | Acid concentration (0.03-0.14M), temperature (121°C) | Plant proteins (wheat gluten, rice); improves emulsification | ↑ Solubility, ↑ Emulsification |

| Phosphorylation [25] | Adds phosphate groups; increases electronegativity | STMP/STMP concentration (1-6%), pH 9.0 | Perilla, soy protein; enhances foam stability | ↑ Solubility (to 92%), ↑ Foaming |

| Glycosylation [25] | Attaches hydrophilic glycans; alters hydrophilicity | Dry-heat (60°C), 65% humidity, 1-4 sugar:protein ratio | Egg white, casein; improves gel properties | ↑ Gel strength, ↑ Thermal stability |

| Acylation [25] | Adds hydrophobic chains; modifies interactions | Succinic anhydride, pH 8.0, 5% protein concentration | Oat protein, myofibrillar proteins | ↑ Solubility, ↑ Emulsifying properties |

| Additive Stabilization [24] | Various mechanisms depending on additive | Glycerol (5-20%), DTT (1-5mM), EDTA (1-5mM) | Short-term storage & processing | Maintains native state, prevents aggregation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Protein Stability Research

This table details essential reagents used in protein stability and solubility research, with their specific functions and application notes.

| Reagent | Function | Example Applications | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uranyl Formate (0.75%) | Negative stain for EM; enhances contrast | Sample quality assessment; single-particle EM [26] | Light-sensitive; adjust with NaOH to prevent precipitation |

| Sodium Trimetaphosphate (STMP) | Phosphorylating agent | Chemical phosphorylation of serine/threonine residues [25] | Use at alkaline pH (8.0-9.0); requires purification post-reaction |

| Succinic Anhydride | Acylating agent | Lysine residue acylation to modify surface properties [25] | Control pH carefully during reaction; unreacted reagent must be removed |

| Glycerol | Cryoprotectant, osmolyte | Storage buffer additive (5-20%) to prevent aggregation [24] | High viscosity can affect some assays; use lower concentrations for kinetics |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reducing agent | Preventing intermolecular disulfide formation (1-5 mM) [24] | Unstable in solution; prepare fresh or store frozen aliquots |

| EDTA/EGTA | Chelating agents | Metalloprotease inhibition (1-5 mM) [24] | Removes essential metal cofactors for some proteins; test for activity retention |

Experimental Workflows and Structural Relationships

Protein Stability Analysis Workflow

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow for analyzing and addressing protein stability issues, integrating both computational and experimental approaches:

Structural Vulnerabilities to Functional Deficits

This diagram illustrates the conceptual framework connecting different types of structural vulnerabilities to their resulting functional deficits and potential remediation strategies:

Molecular Engineering and Computational Solutions for Enhanced Stability

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Enhancing Protein Solubility and Stability

FAQ 1: What are the primary strategies when my recombinant protein is expressed insolubly in E. coli?

You can approach the problem through two complementary paradigms: intrinsic molecular redesign and extrinsic folding modulation [2] [29].

- Intrinsic Molecular Redesign: Modify the protein's own sequence to improve its folding characteristics. This includes:

- Truncation: Removing unstructured or aggregation-prone terminal regions [2].

- Rational Design & Directed Evolution: Using structure-based knowledge or random mutagenesis with screening to introduce solubility-enhancing mutations [2] [30].

- Ancestral Reconstruction: Inferring and synthesizing ancient protein sequences that are often more stable [2].

- Extrinsic Folding Modulation: Adjust the expression environment to assist folding. This includes:

- Molecular Chaperone Co-expression: Overexpressing host chaperones like GroEL/GroES and DnaK/DnaJ to guide proper folding [2].

- Fusion Tags: Adding solubilizing partners like MBP, GST, or NusA to the N- or C-terminus of the target protein [2].

- Culture Condition Optimization: Using lower induction temperatures or adding chemical chaperones like glycerol and arginine to the culture medium [2].

FAQ 2: Why does enhancing my enzyme's activity through directed evolution often result in reduced stability, and how can I avoid this?

This common problem, known as an activity/stability trade-off, occurs because mutations that improve activity—often in the active site—can disrupt the optimized network of intramolecular interactions that stabilize the protein's native structure [30]. For example, active-site mutations may create steric strain or unsatisfied interactions that destabilize the folded state [30].

Solutions to overcome this trade-off:

- Incorporate Stability Screens: Perform high-throughput stability screening (e.g., using thermal shift assays) in parallel with activity screens to identify variants that maintain or improve both properties [30].

- Use Compensatory Mutations: After identifying an activity-enhancing but destabilizing mutation, perform subsequent rounds of evolution to find second-site compensatory mutations that restore stability, often at positions distal to the active site [30].

- Leverage Computational Design: Use advanced inverse folding models like ABACUS-T, which can redesign protein sequences to significantly enhance thermostability (e.g., ∆Tm ≥ 10 °C) while maintaining or even improving functional activity by considering multiple conformational states and evolutionary information [31].

FAQ 3: What is a practical experimental method to quickly identify which protein domains can be functionally fused?

Incremental Truncation for the Creation of Hybrid Enzymes (ITCHY) is a powerful method for this purpose [32] [33].

- Principle: ITCHY creates a comprehensive library of hybrid proteins by fusing two genes or gene fragments at virtually every possible single-amino-acid position, independent of their DNA sequence homology.

- Procedure: A key implementation, THIO-ITCHY, involves the random incorporation of α-phosphothioate dNTPs into DNA during a fill-in reaction or PCR. Subsequent exonuclease III treatment digests the DNA but stops at the phosphothioate linkages, creating a library of fragments of varying lengths. Ligation of these fragments generates the fusion library [32].

- Application: This method allows you to rapidly screen for functional hybrid enzymes by testing which fusion points yield active proteins, solving the "where to fuse" problem without requiring predefined domain boundaries [33].

Key Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol 1: Creating an Incremental Truncation (THIO-ITCHY) Library

This protocol enables the generation of a library of hybrid proteins [32].

- Vector Construction: Clone the two gene fragments of interest (Fragment A and Fragment B) into a single plasmid vector, separated by a short linker sequence.

- Linearization: Restriction digest the plasmid to linearize it at a unique site between the two fragments.

- DNA Spiking (Phosphothioate Incorporation):

- Option A (Exonuclease/Klenow): Treat the linearized DNA with exonuclease III to create a single-stranded overhang. Use Klenow fragment (exo-) with a mixture of natural dNTPs and α-phosphothioate dNTPs (αS-dNTPs) to fill in the overhang, randomly incorporating phosphothioate linkages.

- Option B (PCR): Amplify the linearized plasmid via PCR using a mixture of dNTPs and αS-dNTPs.

- Truncation Library Creation: Treat the spiked DNA with exonuclease III. The enzyme will digest the DNA until it encounters a phosphothioate linkage, creating a mixture of fragments with different lengths.

- Blunt-Ending and Ligation: Treat the digested DNA with mung bean nuclease to remove single-stranded overhangs, then with Klenow fragment to ensure all ends are blunt. Cyclize the plasmid via intramolecular ligation.

- Transformation and Screening: Transform the ligation product into a suitable E. coli host and screen the resulting colonies for the desired functional hybrid.

Quantitative Comparison of Molecular Modification Strategies

The table below summarizes the core strategies for enhancing protein solubility and stability [2] [31] [30].

| Strategy | Key Methodology | Typical Mutations Tested | Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Truncation | Removal of unstructured terminal domains. | N/A | Reduces aggregation propensity; simple to implement. | Requires knowledge of domain structure; may compromise function. |

| Rational Design | Structure-based introduction of specific mutations. | Few, targeted mutations. | High precision; targets known problem areas. | Requires high-resolution structural data; limited by design knowledge. |

| Directed Evolution | Iterative random mutagenesis and screening. | Few mutations per round (requires multiple rounds). | No structural information needed; can discover novel solutions. | Prone to activity/stability trade-offs; screening is labor-intensive [30]. |

| Ancestral Reconstruction | Computational inference of ancient sequences. | Dozens of mutations simultaneously. | Can yield highly stable proteins; tests deep functional constraints. | Relies on availability and quality of multiple sequence alignments. |

| Inverse Folding (ABACUS-T) | AI-based sequence redesign for a given structure. | Dozens of mutations simultaneously [31]. | Large stability gains (∆Tm ≥ 10°C); can maintain function [31]. | Complex computational pipeline; requires a 3D structure as input [31]. |

Workflow and Strategy Diagrams

Diagram 1: Strategic Selection of Molecular Modification Approaches

This diagram outlines a decision-making workflow for selecting the most appropriate optimization strategy based on the characteristics of the target protein [2].

Diagram 2: Directed Evolution Experimental Workflow

This chart illustrates the standard iterative cycle of directed evolution, highlighting the key bottleneck where stability trade-offs often occur [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The table below lists essential reagents and tools used in the featured strategies and experiments.

| Research Reagent | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| α-Phosphothioate dNTPs | Creates exonuclease-resistant sites in DNA. | Essential for the THIO-ITCHY protocol to generate incremental truncation libraries [32]. |

| Exonuclease III | Processively digests double-stranded DNA from blunt or 5'-overhanging ends. | Used in THIO-ITCHY to digest DNA until it encounters an incorporated phosphothioate nucleotide [32]. |

| Molecular Chaperones (GroEL/ES, DnaK/J) | Assist in the proper folding of nascent polypeptide chains in the cell. | Co-expressed with recombinant proteins in E. coli to reduce aggregation and increase soluble yield [2]. |

| Chemical Chaperones (Glycerol, Argining) | Stabilize proteins in solution by altering solvent properties. | Added to culture medium or purification buffers to suppress aggregation and promote correct folding [2]. |

| Fusion Tags (MBP, GST, NusA) | Act as solubility enhancers by providing a folding scaffold. | Fused to the N- or C-terminus of insoluble target proteins to improve their expression solubility [2]. |

| ABACUS-T Model | A multimodal inverse folding model for protein sequence redesign. | Redesigns protein sequences to enhance thermostability while preserving functional activity and dynamics [31]. |

What are fusion tags and why are they used?

Fusion tags are known proteins or peptides that are attached to a protein of interest (POI) using recombinant DNA technology [34]. Researchers use them for several key reasons:

- Purification and Detection: They enable isolation and detection of a protein without a specific antibody [34] [35].

- Solubility Enhancement: They can prevent aggregation and promote correct folding of recombinant proteins [36] [2].

- Versatility: Multiple tags can be attached to the same protein, and they can be used for various applications including live-cell imaging and pull-down assays [34].

What are the advantages and disadvantages of using fusion tags?

Advantages include the ability to isolate proteins without specific antibodies, possibility of tag cleavage after purification, and avoidance of antibody interference in immunoprecipitation [34]. Disadvantages include the potential for tags to affect protein functionality and the often empirical, trial-and-error process for optimal tag placement [34].

Mechanisms of Solubility Enhancement

How do fusion tags enhance protein solubility?

Fusion tags enhance solubility and promote proper folding through several distinct mechanisms [2] [37]:

- Folding Nuclei and Intramolecular Chaperones: Some tags provide stable structural frameworks that guide the folding of the fused protein.

- Chaperone Recruitment: Certain tags can recruit host chaperone systems to assist with folding.

- Increased Electrostatic Repulsion: Tags with charged surfaces can increase protein solubility through charge repulsion that prevents aggregation.

- Reduced Degradation: Fusions can protect recombinant proteins from proteolytic degradation by cellular proteases.

- Compartmentalization: Some tags can translocate fusion proteins to different cellular compartments with more favorable folding environments.

What is the molecular basis for solubility enhancement in different tag types?

Different classes of tags employ distinct molecular strategies [36] [38]:

- Structured Protein Tags (e.g., MBP, NusA): Act as folding scaffolds by providing a stable folded domain that guides proper folding of the target protein.

- Intrinsically Disordered Tags (SynIDPs): Function as "entropic bristles" with high conformational freedom that prevent aggregation through steric and charge effects.

- Small Solubility Motifs (e.g., NT11): Short, acidic peptides that enhance solubility through surface charge modulation without adding substantial structural constraints.

Fusion Tag Selection Guide

How do I choose the right fusion tag for my experiment?

Selecting the appropriate fusion tag requires considering several experimental factors [34] [39]:

- Application Purpose: Determine if you need the tag for purification, solubility enhancement, detection, or multiple functions.

- Protein Characteristics: Consider your protein's size, structure, and potential aggregation tendencies.

- Tag Size: Larger tags are often better for structural studies, while smaller tags are preferable for physiological interactions.

- Expression System: Consider compatibility with your host organism (bacterial, mammalian, etc.).

- Downstream Applications: Evaluate whether the tag needs to be removed and what detection methods you'll use.

Comparison of Commonly Used Fusion Tags

Table 1: Protein-Based Fusion Tags for Solubility Enhancement

| Tag Name | Size | Solubility Enhancement | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP) | ~42 kDa | Strong | Powerful solubility enhancer; affinity purification on amylose resin | Large size may alter activity; may require removal [36] |

| NusA | ~55 kDa | Very Strong | Exceptional solubility enhancement for difficult proteins | Very large size; usually requires removal [36] |

| Thioredoxin (Trx) | ~12 kDa | Moderate-Strong | Enhances folding in E. coli; improves solubility | Limited purification use; may require removal [36] |

| SUMO | ~11 kDa | Moderate-Strong | Enhances folding/solubility; precise cleavage by SUMO protease | Requires SUMO protease; adds extra step [36] |

| Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST) | 26 kDa (monomer) | Moderate | Affinity purification with glutathione resin; dimerization | Dimerization may alter activity; can lead to false positives in IP [36] [35] |

| GFP | ~27 kDa | Moderate | Direct fluorescence monitoring; stabilizes fusion proteins | Moderate size; may affect folding/function [36] |

| HaloTag | 34 kDa | Moderate | Covalent binding to ligands; compatible with prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems | Large size; may require cleavage for some applications [35] |

| Fc | 25 kDa (monomer) | Moderate | Protein A/G affinity purification; increases stability and half-life | Large size; promotes dimerization [36] |

Table 2: Peptide-Based Tags and Emerging Technologies

| Tag Name | Size | Solubility Enhancement | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyhistidine (6xHis) | ~0.8 kDa | None | Minimal effect on structure; works under denaturing conditions | No solubility enhancement; background binding in mammalian cells [35] [39] |

| NT11 | ~1.2 kDa | Moderate | Very small size; works at N- or C-terminus; minimal interference | Newer technology with less characterization [40] |

| SynIDPs | 10-20 kDa | Moderate-High | Designed for minimal interference; maintain protein activity | Custom design required; relatively new technology [38] |

| FLAG | ~1.0 kDa | Minimal | High specificity; low background; minimal effect on protein function | Low yield in purification; no solubility enhancement [39] |

| HA | ~1.2 kDa | Minimal | Small size; high specificity; minimal disruption | Cleaved by caspases in apoptotic cells; no solubility enhancement [39] |

| HiBiT | 1.2 kDa | Minimal | Very small; high editing efficiency with CRISPR; sensitive detection | No solubility enhancement; requires complementation for detection [35] |

Which tags are most effective for enhancing solubility?

Comparative studies reveal the following general ranking for solubility enhancement [37]:

- SUMO and NusA (consistently high solubility enhancement)

- Ubiquitin and MBP (moderate to strong enhancement)

- Thioredoxin and GST (variable performance depending on target protein)

However, these rankings are protein-dependent, and empirical testing is often necessary.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

What should I do if my fusion protein is still insoluble?

When facing insoluble expression, consider these systematic approaches [34] [2]:

- Tag Switching: If one tag doesn't work, try a different solubility tag with a distinct mechanism (e.g., switch from GST to MBP or NusA).

- Tag Position: Test both N-terminal and C-terminal fusions, as positioning can dramatically affect solubility.

- Linker Optimization: Modify the linker sequence between the tag and your protein—try flexible (e.g., GGS repeats) or cleavable linkers.

- Expression Condition Screening: Reduce expression temperature (16-30°C), use lower inducer concentrations, or try autoinduction media.

- Chaperone Co-expression: Co-express molecular chaperones like GroEL/GroES, DnaK/DnaJ, or Trigger Factor.

- Chemical Chaperones: Add arginine, glycerol, or cyclodextrins to your culture medium or lysis buffer.

How can I address low protein yield despite soluble expression?

For low yield issues, consider these strategies [2] [37]:

- Promoter Optimization: Use strong, regulated promoters (e.g., T7, tac) with optimal induction timing.

- Codon Optimization: Adapt codon usage to your expression host, particularly for rare codons.

- Strain Selection: Test different expression strains (e.g., BL21, Origami, Rosetta) for enhanced yield.

- Fusion Tag Size Consideration: Use smaller tags (e.g., SUMO, NT11) to increase mass yield of the target protein.

- Protease Inhibition: Include protease inhibitor cocktails in lysis buffers and use protease-deficient strains.

What if the fusion tag interferes with protein function or activity?

When tag interference occurs [34] [35]:

- Implement Tag Removal: Incorporate specific protease sites (TEV, PreScission, Factor Xa) for tag cleavage after purification.

- Try Smaller Tags: Switch to minimal tags like His-tag, NT11, or FLAG that are less likely to interfere.

- Use Structured vs. Disordered Tags: For steric interference, try intrinsically disordered tags (SynIDPs) that are less likely to affect folding.

- Test Multiple Constructs: Create both N-terminal and C-terminal fusions to find the optimal configuration.

Tag Removal and Cleavage Strategies

When and how should I remove fusion tags?

Tag removal is recommended when the tag interferes with protein function, structure, or downstream applications. Key considerations include [36] [35]:

- Protease Selection: Choose specific proteases that minimize non-specific cleavage (TEV protease is popular for its high specificity).

- Cleavage Site Design: Incorporate optimized recognition sequences between the tag and target protein.

- Purification Strategy: Plan for removing the protease and cleaved tag after processing (often using a second affinity step).

- Cost-Benefit Analysis: Balance the benefits of tag removal against the additional steps and potential yield loss.

Table 3: Common Proteases for Tag Removal

| Protease | Recognition Sequence | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEV Protease | ENLYFQ\G | High specificity; active in various buffers | Requires elevated temperatures for optimal activity [35] |

| SUMO Protease | SUMO protein structure | Extremely precise; naturally cleaves at SUMO fold | Only works with SUMO tags [36] |

| Thrombin | LVPR\GS | Well-characterized; commercially available | Lower specificity; potential non-target cleavage |

| Factor Xa | IEGR\ | Specific cleavage; works well for secreted proteins | Can exhibit promiscuity with similar sequences |

| PreScission Protease | LEVLFQ\GP | High specificity; active at low temperatures | Requires specific buffer conditions |

Advanced and Emerging Technologies

What are the latest developments in fusion tag technology?

Recent advances are addressing limitations of traditional tags [38] [40]:

- Synthetic Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (SynIDPs): De novo designed disordered tags (10-20 kDa) that enhance solubility with minimal effect on protein activity, often eliminating the need for tag removal [38].