Addressing Proteolysis in Protein Purification: From Workflow Challenges to Targeted Degradation Technologies

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of proteolysis in protein workflows, addressing both the challenge of unwanted protein degradation during purification and the opportunity of intentional proteolysis for therapeutic purposes.

Addressing Proteolysis in Protein Purification: From Workflow Challenges to Targeted Degradation Technologies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of proteolysis in protein workflows, addressing both the challenge of unwanted protein degradation during purification and the opportunity of intentional proteolysis for therapeutic purposes. We first explore the fundamental causes and impacts of protease contamination in traditional protein production. The discussion then progresses to advanced methodological applications, including the engineering of proteases with tailored specificity and the revolutionary PROTAC platform for targeted protein degradation in drug development. A dedicated troubleshooting section offers practical strategies for optimizing buffer systems, fusion tags, and expression conditions to prevent unwanted proteolysis, supported by large-scale statistical trends. Finally, we examine cutting-edge validation techniques, from machine learning-driven protease engineering to non-invasive monitoring systems, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a holistic framework for navigating the dual nature of proteolysis in both basic research and clinical translation.

Understanding Proteolysis: Fundamental Challenges in Protein Stability and Purification

In the context of protein purification workflows, proteolysis presents a dual challenge. It is a fundamental biological process defined as the breakdown of proteins into smaller polypeptides or amino acids [1] [2] [3]. For researchers, it manifests in two distinct ways:

- Unwanted Degradation: An experimental obstacle where valuable recombinant or purified proteins are inadvertently hydrolyzed by proteases, compromising yield, homogeneity, and activity [4] [5] [6].

- Targeted Protein Removal: An advanced technological tool that deliberately hijacks cellular proteolysis mechanisms to eliminate specific disease-associated proteins [7] [8] [9].

This technical support guide is designed to help you troubleshoot the common problem of unwanted proteolysis and introduces the foundational principles of targeted degradation platforms like PROTACs that are revolutionizing drug discovery.

FAQs: Troubleshooting Unwanted Proteolysis in Purification

What are the primary indicators of proteolysis during my purification?

You can identify proteolysis through several tell-tale signs in your experimental results:

- Multiple Lower-Molecular-Weight Bands on an SDS-PAGE gel, especially below your protein of interest, indicating cleavage fragments [6].

- Reduced Yield or Loss of Activity in your final protein preparation, even when mRNA levels are detectable [4].

- Inability to Obtain a Homogeneous Sample after affinity purification, as proteolytic fragments containing the affinity tag will co-purify with the full-length protein [6].

Which types of proteins are most susceptible to proteolysis?

Proteins with certain structural characteristics are inherently more prone to degradation. These include:

- Proteins with long, exposed, unstructured loops or intrinsically disordered regions that are accessible to proteases [1] [6].

- Unstable proteins, misfolded proteins, and some mutant proteins [1] [6].

- Proteins rich in specific amino acid sequences (e.g., PEST sequences rich in Proline, Glutamic acid, Serine, and Threonine) are known to have short half-lives [1].

What practical steps can I take to prevent proteolysis during cell lysis and purification?

A two-pronged strategy of inhibition and rapid separation is most effective [5]. Key methods are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Strategies to Prevent Unwanted Proteolysis During Protein Purification

| Method | Protocol / Solution | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Add a commercial broad-spectrum cocktail to all lysis and purification buffers. | Quickly inhibits a wide range of protease classes (serine, cysteine, metallo-, etc.) [5]. |

| Cold Temperature | Perform all steps after cell harvest at 4°C. | Slows down enzymatic activity, including proteolysis [5]. |

| Rapid Processing | Minimize the time between lysis and the first chromatography step. | Reduces the window for proteolysis to occur [5] [6]. |

| Filter Flow-Through Purification | Pass the crude lysate or purified sample through a low-protein-binding filter (e.g., 0.1 or 0.22 µm). | Rapidly removes aggregated proteolytic products that are retained by the filter, while full-length protein flows through [6]. |

Are there expression strategies that can minimize proteolysis in planta or in microbial systems?

Yes, optimizing the expression system itself can significantly reduce in vivo degradation:

- Modulate Expression Conditions: Slowing protein expression by lowering the induction temperature, shortening expression time, or using less rich media can decrease aggregation and proteolysis [6].

- Use Protease-Deficient Strains: For microbial expression, use commercially available protease-deficient strains (e.g., for E. coli) [4].

- Employ Organelle-Specific Targeting: In plant systems, targeting protein accumulation to specific organelles or using tissue-specific promoters (e.g., seed-specific) can shield the protein from highly proteolytic environments [4].

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Workflow for Proteolysis Prevention

The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for purifying a susceptible protein, incorporating key steps to mitigate degradation.

Materials

- Lysis Buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0)

- Complete, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets

- Affinity Purification Resin (e.g., Ni-NTA Agarose for His-tagged proteins)

- Syringe Filter Units (0.22 µm or 0.45 µm, low protein binding)

Procedure

Harvesting and Lysis:

- Harvest cells by centrifugation.

- Resuspend cell pellet in ice-cold Lysis Buffer containing a freshly added protease inhibitor cocktail.

- Lyse cells using your preferred method (e.g., sonication, French press) while keeping the sample on ice.

Clarification and Filtration:

- Centrifuge the lysate at high speed (e.g., 15,000 x g for 20 min at 4°C) to remove insoluble debris.

- Critical Step: Immediately pass the clarified supernatant through a syringe filter unit. This step rapidly removes aggregated proteolytic products [6].

Affinity Chromatography:

- Incubate the filtered lysate with the pre-equilibrated affinity resin for a defined, short period (e.g., 1 hour at 4°C) to minimize contact time with potential contaminants.

- Wash the resin with Wash Buffer (containing protease inhibitors) to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

Elution and Storage:

- Elute the target protein with Elution Buffer. Keep the eluate on ice.

- Proceed immediately to the next purification step or flash-freeze the protein in small aliquots using liquid nitrogen for storage at -80°C to prevent degradation during storage.

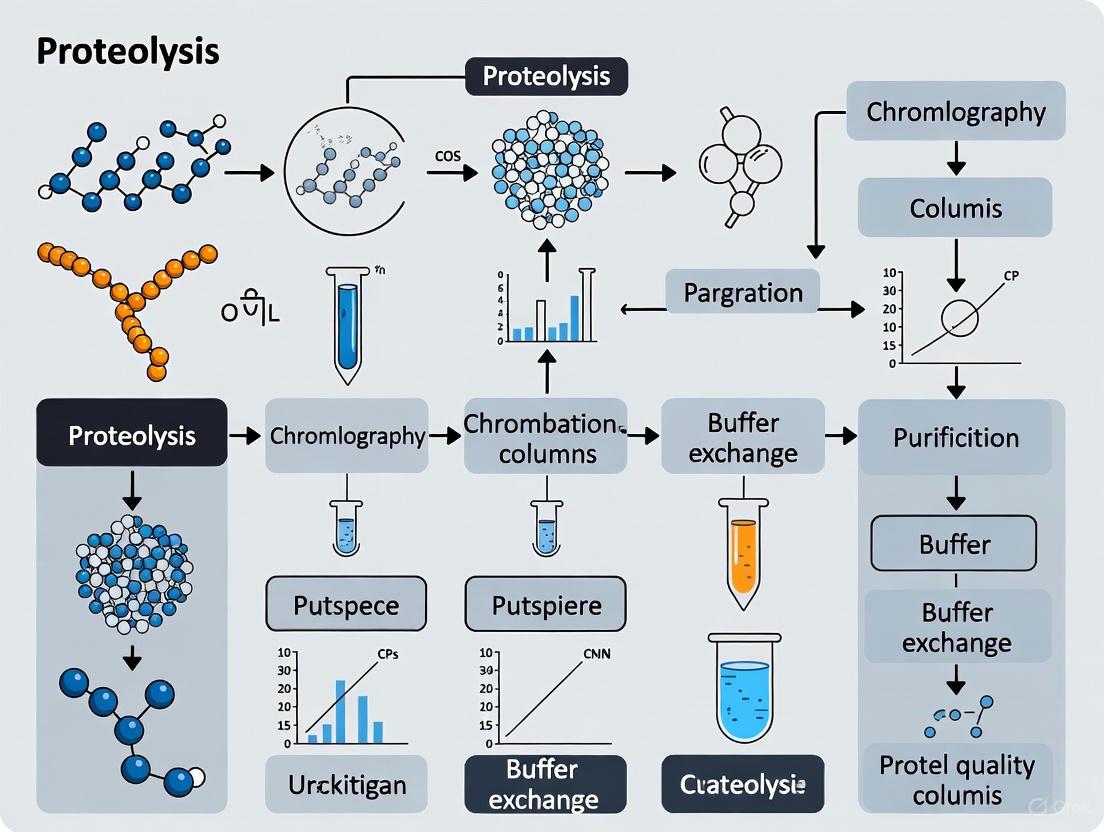

Diagram 1: Proteolysis prevention workflow.

Fundamentals of Targeted Protein Removal

While unwanted proteolysis is a problem to solve, controlled proteolysis is a powerful tool. Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD) technologies, particularly PROteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs), are a breakthrough therapeutic strategy [8] [9].

What is a PROTAC?

A PROTAC is a heterobifunctional small molecule with three components [7] [8]:

- A warhead that binds to a Protein of Interest (POI).

- A ligand that recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase.

- A linker connecting the two.

How does a PROTAC work?

The mechanism involves hijacking the cell's natural ubiquitin-proteasome system, as illustrated below.

Diagram 2: PROTAC mechanism of action.

- Ternary Complex Formation: The PROTAC molecule simultaneously binds to the target protein (POI) and an E3 ubiquitin ligase, forming a ternary complex [7] [8].

- Ubiquitination: The E3 ligase transfers ubiquitin chains onto the POI, marking it for destruction [8] [9].

- Degradation: The ubiquitinated POI is recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome into small peptides and amino acids [1] [7].

- Recycling: The PROTAC is released unchanged and can catalyze another round of degradation, functioning substoichiometrically [8].

What are the key advantages of PROTACs over traditional inhibitors?

- Targets "Undruggable" Proteins: PROTACs require only binding to the target protein, not functional inhibition, opening up previously inaccessible proteins for drug development [7] [9].

- Catalytic Activity: A single PROTAC molecule can degrade multiple copies of the target protein, allowing for lower and less frequent dosing [8].

- Eliminates All Functions: By degrading the entire protein, PROTACs abolish all its functions (e.g., enzymatic and scaffolding), which can lead to more profound therapeutic effects [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table outlines essential reagents used in the fields of proteolysis prevention and targeted protein degradation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Proteolysis Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Broad-Spectrum Protease Inhibitors | Added to lysis buffers to inactivate a wide range of proteases (e.g., serine, cysteine, metalloproteases) during protein extraction and purification [5]. |

| PROTAC Molecule | A heterobifunctional degrader used to induce targeted ubiquitination and degradation of a specific protein of interest for research or therapeutic purposes [7] [8]. |

| E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Ligands | Key components of PROTACs that recruit specific E3 ligases (e.g., VHL, CRBN) to the target protein complex [7] [9]. |

| TR-FRET Assay Kits | Used to monitor key steps in targeted degradation, such as ternary complex formation and protein ubiquitination, in a high-throughput format [8]. |

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Kits | Utilize affinity resins to isolate and analyze polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates to confirm PROTAC mechanism of action [8]. |

Protease contamination is a significant challenge in cellular expression systems, often leading to reduced yield, degraded products, and unreliable experimental results in protein purification workflows. Understanding the sources of these proteases and implementing robust detection and prevention strategies is crucial for successful research and drug development. This guide provides a technical overview and troubleshooting resource for managing protease-related issues.

FAQ: Frequent Issues and Rapid Solutions

Q1: My purified recombinant protein shows multiple lower molecular weight bands on SDS-PAGE. Is this protease contamination? Yes, this is a classic sign of proteolysis during expression or purification. Proteolytic cleavage produces protein fragments that co-purify with your target, appearing as extra bands. To confirm, run a protease activity assay and check if adding protease inhibitors during purification reduces the bands [6].

Q2: I am using E. coli for expression. What are the most common sources of proteases? In E. coli, proteases like Lon, DegP, and OmpT are major contaminants. They are often released during cell lysis. Using protease-deficient E. coli strains can help, but intrinsic proteolytic activity remains a concern, especially for susceptible proteins [6].

Q3: How does the choice of expression system (mammalian vs. bacterial) influence protease contamination? The profile of contaminating proteases differs significantly:

- Mammalian Systems (e.g., Expi293): Contain endogenous cathepsins (B, L, S) and other lysosomal proteases. These are cysteine proteases and require specific inhibitors [10].

- Bacterial Systems (e.g., E. coli): Produce a different set of proteases like Lon, DegP, and OmpT, which are primarily serine proteases [6]. The mammalian system may provide more physiologically relevant post-translational modifications but introduces a different set of contaminants to manage.

Q4: What is a quick method to remove pre-formed proteolytic fragments from my full-length protein sample? For proteolytic products that have already formed and aggregated, filter flow-through purification can be effective. This rapid technique leverages the tendency of cleaved fragments to aggregate. The full-length protein passes through a filter, while the aggregated fragments are retained. This process can be completed in minutes, much faster than dialysis or gel filtration [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Detection and Prevention of Protease Contamination

Detection and Confirmation of Protease Activity

Before troubleshooting, confirm that your issue is due to protease activity.

- Suspected Cause: Nonspecific protein degradation observed as smearing or unexpected bands on SDS-PAGE.

- Solution: Fluorometric Protease Activity Assay

- Principle: This assay uses a quenched, fluorescently-labeled protein substrate (e.g., FITC-casein). Protease cleavage unquenches the fluorophore, increasing fluorescence measurable with a plate reader [11].

- Protocol Summary:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute cell culture supernatant, lysate, or purified sample in assay buffer. Avoid protease inhibitors at this stage [11].

- Reaction Setup: Add 50 µL of sample to a well. Add 50 µL of Reaction Mix (assay buffer containing FITC-casein substrate) [11].

- Measurement: Read fluorescence immediately (Ex/Em = 485/530 nm) as your initial reading (T1). Incubate at 25°C for 30 minutes protected from light, then take a second reading (T2) [11].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the change in fluorescence (ΔRFU = R2 - R1). Compare to a standard curve to quantify activity. One unit of activity is defined as the amount of protease that generates fluorescence equivalent to 1.0 µmol of unquenched FITC per minute [11].

Addressing Endogenous Proteases in Mammalian Expression Systems

Mammalian cells, such as the Expi293 system, naturally produce active proteases like cathepsins, which can co-purify with your protein of interest [10].

- Suspected Cause: Co-purification of host cell proteases (e.g., Cathepsins B, L, S) leading to ongoing degradation during and after purification.

- Solution: Optimized Purification from Mammalian Culture Media

- Principle: Efficiently capturing the secreted pro-form of the protease and controlling its activation to prevent degradation.

- Protocol Summary (based on cathepsin purification):

- Harvesting: Collect culture media 3 days post-transfection. The target proteases are often secreted into the media in an inactive pro-form [10].

- Buffer Exchange: Dialyze the media against a compatible buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol) to prepare for Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC) [10].

- Purification: Use Ni-NTA affinity chromatography if your protein is His-tagged. Note that both the pro-form and mature, autocleaved forms may be present in the elution [10].

- Handling: Maintain a pH above 6 during purification to prevent autocatalytic activation and denaturation that can occur in acidic conditions [10].

Preventing Proteolysis in Bacterial Expression Systems

Bacterial lysates are particularly rich in proteases that are released upon cell disruption.

- Suspected Cause: Protease release during bacterial cell lysis, degrading the target protein.

- Solution: Integrated Prevention Strategy

- Principle: Combine genetic, biochemical, and procedural methods to minimize proteolysis.

- Protocol Summary:

- Strain Selection: Use protease-deficient E. coli strains (e.g., lacking Lon and OmpT proteases) [6].

- Expression Control: Slow protein expression by lowering the incubation temperature after induction (e.g., to 4°C) and using less rich media. This reduces aggregation and misfolding, making the protein less susceptible to proteases [6].

- Lysis Conditions: Always perform lysis on ice or in a cold room. Include a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor cocktail in the lysis buffer. For proteins extremely susceptible to proteolysis, consider purification under denaturing conditions [6].

The table below summarizes key proteases found in different expression systems, their classification, and common triggers for their activity.

| Expression System | Common Contaminating Proteases | Protease Class | Primary Source / Trigger |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mammalian (e.g., Expi293) | Cathepsin B, L, S [10] | Cysteine Protease | Endogenous lysosomal proteases; Auto-activation at low pH [10] |

| Bacterial (e.g., E. coli) | Lon, DegP, OmpT [6] | Serine Protease | Released during cell lysis; Target unstable proteins or those with unfolded regions [6] |

| General | Various (e.g., from serum in culture media) | Mixed | Introduced via contaminated reagents or poor aseptic technique |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Managing Proteolysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Troubleshooting Proteolysis |

|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Broad-spectrum or specific cocktails (e.g., targeting cysteine proteases) added to lysis and purification buffers to inactivate contaminating proteases. |

| Protease-Deficient E. coli Strains | Expression hosts genetically engineered to lack key bacterial proteases (e.g., Lon, OmpT), reducing degradation at the source [6]. |

| Fluorometric Protease Assay Kit | A quantitative, mix-and-read kit for confirming and measuring protease activity in samples using a FITC-casein substrate [11]. |

| Ni-NTA Affinity Resin | For efficient one-step purification of His-tagged recombinant proteins from complex mixtures like cell culture media, helping to separate the target from proteases [10]. |

| Filtration Devices (Filter Flow-Through) | A rapid method to separate full-length protein from aggregated proteolytic products based on size, completed in minutes [6]. |

Workflow Diagram: Managing Protease Contamination

The following diagram outlines a logical pathway for diagnosing and addressing protease contamination in protein purification workflows.

Impact of Proteolysis on Protein Yield, Function, and Structural Integrity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is proteolysis and why is it a major concern in protein production? Proteolysis is the enzymatic process by which proteins are broken down into smaller peptides or amino acids. In the context of biopharmaceutical production, it is a critical concern because it can degrade therapeutic proteins, directly impacting final yield, product homogeneity, biological activity, and overall quality. Unlike simpler pharmaceuticals, recombinant proteins have a natural tendency toward structural heterogeneity, and proteolytic processing can dramatically alter their structural integrity both during expression (in planta) and after extraction (ex planta) [4].

How can I tell if my recombinant protein is being degraded by proteases? Common signs of proteolytic degradation include:

- The appearance of multiple lower molecular weight bands on an SDS-PAGE gel or Western blot in addition to, or instead of, the expected full-length protein band [4] [12].

- A noticeable reduction in the yield of the full-length, active protein, even when mRNA transcripts are easily detectable [4].

- A loss of biological activity in the final purified product that cannot be explained by other factors like aggregation [4] [12].

My protein is unstable during purification. What immediate steps can I take? To immediately stabilize your protein during purification, implement the following best practices [13] [12]:

- Work Quickly and Cold: Perform all purification steps on ice or in a cold room at 4°C.

- Use Protease Inhibitors: Add broad-spectrum or specific protease inhibitor cocktails to your lysis and purification buffers.

- Prevent Shear Stress: Avoid vigorous pipetting, vortexing, or high-speed centrifugation. Use wide-bore pipette tips and gentle mixing [13].

- Optimize Buffer Conditions: Include stabilizing additives like glycerol, and use reducing agents (e.g., DTT) to prevent oxidation of sensitive cysteine residues [13].

Which host cell proteases are of highest concern in bioprocessing? Host cells contain a wide array of proteases. Recent research highlights serine hydrolases as a particularly high-risk group. These enzymes can persist through the purification process and impact critical quality attributes, such as degrading stabilizing excipients like polysorbates in the final drug formulation. Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) methods have been developed to specifically monitor these troublesome enzymes during process development [14].

Are some expression systems better than others for minimizing proteolysis? Yes, the choice of expression system can significantly impact proteolysis. While all systems have proteases, some strategies include:

- Using Protease-Deficient Strains: For bacterial systems like E. coli, protease-deficient strains are commercially available and routinely used to minimize recombinant protein loss [4].

- Subcellular Targeting: In more complex systems like plants, targeting protein accumulation to specific organelles (e.g., chloroplasts) or using tissue-specific expression (e.g., seed-specific promoters) can shield the protein from the most active proteases [4].

- Extracellular Secretion: Secreting the protein into the culture medium can separate it from intracellular proteases, though extracellular proteases must then be considered [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Yield of Full-Length Protein

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High protease activity in host cell | Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) to identify active proteases [14] | Use protease-deficient host strains; add protease inhibitors to lysis buffer; co-express companion protease inhibitors [4]. |

| Protein degradation during purification | SDS-PAGE/Western blot analysis of samples from each purification step [12] | Keep samples cold; shorten purification time; include stabilizing additives (e.g., glycerol, EDTA) in buffers [13]. |

| Vulnerable protein sequence/structure | Bioinformatic analysis to identify exposed protease cleavage sites | Engineer the protein sequence to remove susceptible sites; fuse to a stable protein tag (e.g., GST, MBP) for protection [4]. |

| Inappropriate expression system | Compare yield and integrity across different systems (bacterial, yeast, mammalian) | Switch to a more compatible system; use tissue-specific or inducible promoters to control expression timing [4]. |

Problem: Protein Inactivation or Loss of Function

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Proteolytic cleavage at critical sites | Functional assay + SDS-PAGE to correlate activity with integrity | Identify and mutate critical cleavage sites; use fusion tags that enhance stability [4]. |

| Oxidation of sensitive residues | Mass spectrometry analysis | Purify under inert atmospheres (N₂, Argon); include reducing agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) in all buffers [13]. |

| Removal of essential cofactors | Activity assay before and after adding cofactors back | Add required cofactors (e.g., metal ions, coenzymes) to purification and storage buffers [12]. |

| Aggregation leading to inactivity | Dynamic light scattering (DLS) or size-exclusion chromatography | Optimize buffer pH and ionic strength; use chaotropes or detergents to prevent aggregation [12]. |

Advanced Diagnostic and Monitoring Techniques

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) for Host Cell Proteases

Activity-based protein profiling is a powerful method for identifying and quantifying the activity of specific classes of proteases, such as serine hydrolases, within complex bioprocess samples. This technique uses reactive, mechanism-based probes that covalently label the active site of target enzymes, allowing for their subsequent purification and identification via LC-MS. This provides a direct readout of active protease levels, not just their concentration, which is crucial for assessing the risk to your product [14].

The workflow for ABPP is as follows:

Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating Proteolysis

The following table lists key reagents and materials used to prevent proteolysis and stabilize proteins during purification workflows.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Broad-spectrum or specific inhibition of serine, cysteine, metallo-, etc., proteases. | Added to lysis and extraction buffers to prevent degradation during cell disruption [4]. |

| Affinity Purification Resins | Rapid, specific capture of target protein to separate it from proteases. | His-tag purification with Ni-NTA resin; antibody purification with Protein A/G resin [16]. |

| Stabilizing Additives (Glycerol, Sucrose) | Reduce protein dynamics and denaturation, making the protein less susceptible to proteolysis. | Included in storage and purification buffers at 5-20% (v/v) to maintain protein stability [13]. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, TCEP) | Prevent formation of incorrect disulfide bonds and oxidation of cysteine residues. | Essential for stabilizing proteins with free cysteines; maintained in buffers at 0.5-5 mM [13]. |

| Tag Cleavage Proteases (rTEV, Enterokinase) | Highly specific proteases for removing affinity tags to restore native protein structure. | rTEV protease cleaves at ENLYFQ*S sequence; Enterokinase cleaves at DDDDK* sequence [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing and Controlling Proteolysis During Purification

Objective: To isolate a recombinant protein with high yield and functional integrity by monitoring and inhibiting proteolysis throughout the purification process.

Materials:

- Lysis Buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl)

- Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (commercial or prepared with AEBSF, E-64, Leupeptin, etc.)

- EDTA (1-10 mM, to inhibit metalloproteases)

- Dithiothreitol (DTT) or Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)

- Affinity chromatography resin (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins) [16]

- SDS-PAGE equipment and reagents

Method:

- Cell Lysis and Extraction:

- Harvest cells and resuspend in ice-cold Lysis Buffer.

- Critical Step: Immediately prior to use, supplement the buffer with a protease inhibitor cocktail and 1-5 mM DTT/TCEP.

- Lyse cells using a gentle method (e.g., lysozyme treatment, mild sonication on ice) to minimize release and activation of proteases [13].

- Clarify the lysate by centrifugation at 4°C to remove debris.

Rapid Capture and Washing:

- Incubate the clarified lysate with the affinity resin at 4°C with gentle mixing. Reducing the flow rate or stopping the column for a short incubation can improve binding if the target protein level is low [12].

- Wash the resin with >10 column volumes of Wash Buffer (Lysis Buffer with added salt, e.g., 20-30 mM Imidazole for His-tag purification) to stringently remove nonspecifically bound proteins and proteases [12].

Elution and Stabilization:

- Elute the target protein using the appropriate elution buffer (e.g., 250 mM Imidazole, or low pH buffer). Prepare the elution buffer fresh to ensure efficacy [12].

- Immediately after elution, adjust the buffer conditions if needed (e.g., by dialysis or desalting) to place the protein into a stable storage buffer (e.g., containing glycerol and at an optimal pH).

Monitoring and Analysis:

- At each stage (lysate, flow-through, wash, eluate), take a small sample and analyze by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

- Look for the disappearance of the full-length band or the appearance of lower-weight bands, which indicate where and when degradation is occurring [4] [12].

- Use functional assays to confirm the biological activity of the final eluted protein.

In protein purification workflows, particularly for sensitive recombinant proteins, proteolysis—the enzymatic cleavage of peptide bonds—presents a significant and ubiquitous obstacle. This irreversible post-translational modification can generate protein fragments with altered or lost biological activity, compromising experimental results and structural studies [17]. The challenge intensifies when working with complex proteins such as the Plasmodium falciparum Heme Detoxification Protein (HDP), which is essential for the malaria parasite's survival but notoriously difficult to express in a native, soluble form [18] [19]. This case study examines the specific challenges encountered during HDP recombinant expression and outlines a systematic troubleshooting framework to mitigate proteolysis, preserving protein integrity for downstream analysis.

The HDP Expression Challenge: A Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ: What makes Plasmodium HDP particularly difficult to express recombinantly?

Answer: HDP is an essential protein for the malaria parasite, responsible for detoxifying the heme released during hemoglobin digestion by converting it into inert hemozoin crystals [19]. Despite its importance, HDP has proven exceptionally challenging to express in its native, soluble form in E. coli-based systems. A primary reason is its inherent tendency to form insoluble aggregates or soluble aggregates when heterologously expressed. Furthermore, its functional activity appears critically dependent on its flexible, unstructured N-terminal region, which is highly susceptible to proteolytic degradation or misfolding in recombinant systems [18].

FAQ: What specific strategies were employed to achieve soluble expression of HDP?

Answer: Researchers employed a multi-pronged strategy to tackle HDP's solubility issues [18] [19]:

- Expression of Orthologs: Testing HDP genes from different Plasmodium species (e.g., P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. knowlesi).

- Fusion Tags: Utilizing solubility-enhancing partners like GST and MBP.

- Consensus Sequence Design: Creating a synthetic HDP sequence based on conserved residues across species.

- Chaperone Co-expression: Co-expressing molecular chaperones in E. coli to aid proper protein folding.

- Construct Optimization: Systematically designing N-terminal and C-terminal truncations.

Despite these extensive efforts, only one construct—an HDP with a 44-residue N-terminal truncation and a C-terminal 6-His tag (HDPpf-C10)—was expressed in a soluble form. Surprisingly, this truncated, soluble protein lacked detectable heme-to-hemozoin transformation activity, underscoring the critical role of the N-terminal region for function [18].

Troubleshooting Proteolysis in Protein Purification

Proteolysis becomes a significant concern after cell lysis, as the regulated compartmentalization of proteases within the cell is destroyed, allowing them to come into contact with and degrade the protein of interest [5]. The table below outlines common symptoms of proteolysis and the corresponding solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Proteolysis During Protein Purification

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple unexpected bands on SDS-PAGE gel | Non-specific proteolysis by endogenous proteases released during lysis [5]. | Use protease inhibitor cocktails; Keep samples on ice; Perform purifications quickly at low temperatures [5] [20]. |

| Loss of protein activity/function | Specific cleavage in a critical functional domain (e.g., the N-terminus of HDP) [18]. | Optimize construct (e.g., use truncations, fusion partners); Use more specific protease inhibitors. |

| Low protein yield | Extensive degradation of the target protein. | Combine protease inhibition with early and fast chromatographic separation from proteases [5]. |

| Inconsistent results between purifications | Variable levels of protease activity due to slight differences in cell lysis or handling. | Standardize protocols; Use automated purification systems to increase reproducibility and speed [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Two-Pronged Approach to Avoid Proteolysis

As outlined in the literature, a robust method to prevent proteolysis involves a combination of inhibition and separation [5].

1. Inhibition In Situ

- Prepare Lysis Buffer: Chill the chosen lysis buffer (e.g., M-PER, T-PER, B-PER reagents for mammalian, tissue, or bacterial samples, respectively) on ice [20].

- Add Inhibitors: Supplement the buffer with a broad-spectrum, ready-to-use protease inhibitor cocktail. These are available in tablet or liquid form, with options containing EDTA (to inhibit metalloproteases) or being EDTA-free. Phosphatase inhibitors can be added concurrently if preserving phosphorylation status is important [20].

- Lysis: Perform cell lysis in the prepared, chilled buffer. Maintain samples at 0-4°C throughout the lysis process.

2. Early Separation via Chromatography

- After clarification of the lysate by centrifugation, immediately proceed to the first chromatography step.

- Affinity Chromatography (e.g., His-tag or GST-tag purification) is highly effective as an initial capture step because it rapidly separates the target protein from the bulk of cellular proteases.

- For multi-step purification, automation systems (e.g., ÄKTA go) can be configured to run sequential columns (e.g., affinity followed by size-exclusion) without manual intervention, minimizing handling time and the window for proteolysis [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and tools essential for successful recombinant protein expression and purification, especially when combating challenges like proteolysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Expression and Purification

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Examples / Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Inhibits a wide range of protease classes (serine, cysteine, metallo-, etc.) to protect target proteins during and after lysis [20]. | Available as tablets, capsules, or liquids; EDTA-containing or EDTA-free formulations for flexibility [20]. |

| Detergent-Based Lysis Reagents | Gentle, efficient cell lysis with formulations optimized for different sample types (mammalian, bacterial, yeast, tissue) [20]. | M-PER (Mammalian), B-PER (Bacterial), T-PER (Tissue) reagents; minimize cross-contamination between subcellular fractions [20]. |

| Affinity Chromatography Resins | Rapid, specific capture of tagged recombinant proteins, enabling quick separation from proteases. | Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins; Glutathione resin for GST-tagged proteins. |

| Automated FPLC Systems | Enables fast, reproducible, multi-step purification with minimal manual intervention, reducing the time for proteolysis to occur [21]. | ÄKTA go systems, configurable with a column valve and auto-sampler for sequential purification steps [21]. |

| Solubility-Enhancing Fusion Tags | Improves solubility and expression yield of difficult-to-express proteins; can also aid in detection. | GST (Glutathione S-transferase), MBP (Maltose-Binding Protein). |

Workflow and Strategy Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process and strategies used to overcome the challenges of recombinant HDP expression, as detailed in the case study.

The case of Plasmodium HDP highlights that achieving soluble recombinant expression is only half the battle. Functional integrity is paramount. The successful expression of a truncated, soluble HDP that lacked activity underscores a critical lesson: the most soluble construct may not be the most functional. This necessitates a balanced approach where solubility optimization must be continually evaluated alongside functional assays.

The broader strategy for combating proteolysis involves a combination of robust biochemical practices—using protease inhibitors and maintaining cold temperatures—and efficient workflow design that leverages automation and fast purification to minimize the exposure of sensitive proteins to degradative elements [5] [21]. For particularly challenging targets like HDP, extensive construct engineering remains a non-negotiable step in the process, requiring researchers to systematically test various homologs, fusions, and truncations to find a expressible and functional protein variant [18] [19].

FAQ: Understanding the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

What is the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and why is it important? The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is the primary mechanism for regulated, processive degradation of intracellular proteins in eukaryotes [22] [23] [24]. It is responsible for protein homeostasis and quality control, maintaining proper levels of protein expression and removing misfolded or dysfunctional proteins [22]. This tightly regulated process is crucial for numerous cellular functions, including cell cycle regulation, stress response, DNA transcriptional regulation, and apoptosis [22] [25]. Defects in the UPS can lead to various diseases, including cancer, Parkinson's disease, and cystic fibrosis [22].

How are proteins targeted for degradation by the UPS? Proteins are targeted for degradation through a three-step enzymatic cascade that tags them with ubiquitin molecules [22]:

- Activation: Ubiquitin is activated by an E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme in an ATP-dependent reaction.

- Conjugation: The activated ubiquitin is transferred to an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme.

- Ligation: An E3 ubiquitin ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the target protein.

Once a protein is tagged with a single ubiquitin molecule, additional ubiquitin molecules are added to form a polyubiquitin chain, which marks the protein for recognition and degradation by the proteasome [22].

What is the structure of the proteasome and how does it function? The 26S proteasome is a 2.5 MDa multi-subunit complex consisting of two main components [22] [25]:

- 20S Core Particle (CP): A cylindrical structure composed of four rings (two α-rings and two β-rings) with three different proteolytic activities (caspase-like, trypsin-like, and chymotrypsin-like) housed in the inner β-rings.

- 19S Regulatory Particle (RP): A cap complex that recognizes polyubiquitinated proteins, unfolds them, and directs them into the 20S core for degradation in an ATP-dependent manner.

The proteasome's architecture ensures that only unfolded proteins can enter the proteolytic core, making the process highly specific [22].

Is the ubiquitination process reversible? Yes, ubiquitination is a reversible process until proteins become polyubiquitinated and destined for degradation [22]. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) are a family of over 100 enzymes that cleave mono-ubiquitin and polyubiquitin chains from proteins, potentially rescuing specific target proteins from degradation [22]. DUBs are responsible for recycling ubiquitin and play significant roles in various biological processes, including cell growth, differentiation, and transcriptional regulation.

How is the UPS relevant to drug development? The UPS has emerged as a promising therapeutic target, particularly through targeted protein degradation (TPD) strategies [22] [26]. Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) are bifunctional molecules designed to hijack the UPS to selectively degrade disease-causing proteins [26] [27]. Unlike traditional inhibitors that merely block protein activity, PROTACs catalytically eliminate the target protein, offering advantages for targeting "undruggable" proteins such as transcription factors, mutant oncoproteins, and scaffolding molecules [26].

Troubleshooting Common UPS-Related Experimental Issues

Troubleshooting UPS and Protein Degradation Experiments

Table: Troubleshooting Common UPS-Related Experimental Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No protein in eluate | Protein level below binding threshold; Protein not expressed; Protein aggregation; Improperly prepared elution solution [12] | Increase input amount for affinity columns; Check induction system for recombinant proteins; Adjust buffer conditions for stability; Prepare fresh elution solution [12] |

| High background noise | Insufficient washing; Incorrect buffer composition; Resin binding impurities [12] | Add additional wash steps; Optimize wash buffer composition; Reduce total protein sampled; Consider additional purification steps [12] |

| Protein does not bind | Insufficient binding time; Suboptimal binding conditions; Protein tag issues [12] | Reduce flow rate or incubate column; Adjust buffer pH/concentration; Check plasmid sequence or reposition tag [12] |

| Protein degradation during purification | Cellular proteases released during lysis [5] | Use protease inhibitor cocktails; Keep samples on ice or at 4°C; Process samples quickly; Use fast protein liquid chromatography for early protease separation [5] |

| Inconsistent ubiquitination results | Improper handling; Inspecific antibodies; Lack of controls | Use proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins [22]; Validate antibodies; Include appropriate positive/negative controls |

Experimental Protocols for Studying the UPS

Protocol: Detecting Protein Ubiquitination

Purpose: To determine whether a specific protein of interest (POI) has been ubiquitinated.

Materials:

- Ubiquitin Enrichment Kit (for isolation of polyubiquitinated proteins) [22]

- Proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG-132) [22] [25]

- Cell or tissue lysates

- Antibodies against your POI and ubiquitin [22]

- LanthaScreen Conjugation Assay Reagents (for high-throughput screening) [22]

Method:

- Treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., 10-20 μM MG-132) for 4-6 hours before harvesting to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins [22].

- Lyse cells using appropriate lysis buffer with protease inhibitors.

- Isolate polyubiquitinated proteins using a Ubiquitin Enrichment Kit according to manufacturer's instructions [22].

- Elute bound proteins and separate by SDS-PAGE.

- Transfer to membrane and probe with antibody against your POI to confirm ubiquitination [22].

- Alternatively, for more specific detection:

- Immunoprecipitate your POI using a target-specific antibody.

- Perform Western blot with an anti-ubiquitin antibody to detect ubiquitinated forms [22].

Protocol: Assessing Protein Degradation Rates

Purpose: To measure the degradation rate of your protein of interest.

Materials:

- Click-iT Plus protein labeling reagents [22]

- Cycloheximide (for translation inhibition)

- Proteasome inhibitors (optional controls)

Method (Pulse-Chase Analysis):

- Pulse: Label nascent proteins using Click-iT Plus technology with fluorescent labels [22].

- Chase: Replace labeling medium with complete medium and harvest cells at various time points.

- Detect your protein of interest at each time point using specific antibodies or other detection methods.

- Quantify signal intensity and plot against time to determine degradation kinetics.

- Include proteasome inhibitor treatments as controls to confirm UPS-dependent degradation.

Key Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway

Troubleshooting Protein Purification Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Studying the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG-132, Lactacystin [25] | Inhibit proteasomal activity, allowing accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins for study [22] [25] |

| Activity Assay Kits | Proteasome 20S Activity Assay Kit [25] | Measure chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like, or caspase-like proteasome activity using fluorescent substrates |

| Ubiquitination Detection | Ubiquitin Enrichment Kits, LanthaScreen Conjugation Assay [22] | Isolate polyubiquitinated proteins or monitor ubiquitin conjugation rates in high-throughput screens |

| Validated Antibodies | Anti-ubiquitin, Anti-Ubiquitin B [22] | Detect ubiquitin expression and protein ubiquitination in Western blot, ELISA, and protein isolation assays |

| Chromatography Resins | Affinity matrices (agarose, polyacrylamide) [12] | Purify proteins based on specific binding properties; key for separating proteases from proteins of interest [5] [12] |

| PROTAC Molecules | ARV-471 (ER-targeting), ARV-110 (AR-targeting) [27] | Investigate targeted protein degradation for research and therapeutic development |

Advanced Methodologies: Engineering Proteases and Harnessing PROTAC Technology

This technical support center provides a focused resource for researchers integrating a novel DNA-recorder system for protease specificity profiling into their protein purification workflows. Engineered proteases are crucial tools for cleaving fusion tags or modulating protein activity, but their off-target proteolysis can compromise experimental results and protein yields. The methodology outlined here addresses this by enabling the parallel assessment of on- and off-target activities for hundreds of thousands of protease variants, providing the high-quality data necessary to build predictive machine learning models and select highly specific proteases for downstream applications [28] [29].

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guide

System Fundamentals

Q1: What is the core principle behind the DNA-recorder system for profiling protease specificity? The system is a genetic device in E. coli that directly links proteolytic activity to a permanent, sequenceable DNA output. It couples the cleavage of a substrate peptide to the stabilization of a phage recombinase (Bxb1), which in turn catalyzes the inversion of a DNA recombination array. The fraction of inverted arrays in a population, quantifiable via Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), serves as a kinetic measure of proteolytic activity for a specific protease-substrate pair [28].

Q2: What kind of data volume does this system generate, and why is it significant? In a single demonstration, the system profiled approximately 600,000 protease-substrate pairs, testing 29,716 candidate proteases against up to 134 substrates in parallel [28] [29]. This massive scale of sequence-activity data is sufficient to train accurate, data-hungry deep learning models, moving beyond simple variant screening to predictive in-silico protease design.

Q3: How does this method improve the engineering of proteases for therapeutic or precise purification applications? Traditional methods often screen for enhanced on-target activity first and test for problematic off-target cleavage only as a secondary step. This DNA-recorder system profiles activity against dozens of off-target substrates concurrently with the on-target activity during the initial high-throughput step. This allows for the direct selection of variants with desired on-target activity and minimal promiscuity from the outset, a critical feature for therapeutic safety and preserving protein integrity in purification workflows [28].

Experimental Setup & Optimization

Q4: During initial setup, we observe a high background recombination signal even with inactive proteases. How can this be mitigated? A low but consistent background signal is attributed to protease binding without catalytic cleavage, which can partially stabilize the Bxb1-SsrA fusion. This binding contribution remains constant over time, unlike the increasing signal from true proteolysis. You can account for this by:

- Establishing a Threshold: Determine the background flipping fraction using catalytically inactive proteases (e.g., TEVp C151A mutant) and set a minimal activity threshold above which variants are considered active [28].

- Optimizing Linkers: Incorporate flexible amino acid linkers flanking the protease substrate peptide to improve accessibility and the signal-to-background ratio [28].

- Kinetic Analysis: Analyze the flipping fraction over time (the "flipping curve"); a true proteolytic signal will accumulate, whereas the binding signal will be static [28].

Q5: What are the key genetic elements to optimize for maximizing the dynamic range of the recorder? The system's sensitivity depends on the efficient translation of protease activity into recombination. Key optimizations include:

- Promoter/RBS Engineering: Fine-tune the expression levels of both the candidate protease and the Bxb1 recombinase by engineering their promoters and ribosomal binding sites (RBS) [28].

- Induction Timing: Optimize the timing of Bxb1 induction relative to protease expression to ensure the recorder is active during peak protease production [28].

- Degradation Tag: The C-terminal SsrA tag is essential for rapid degradation of Bxb1 in the absence of cleavage. Ensure this degradation signal is intact and functional [28].

Data Generation & Analysis

Q6: Our NGS data processing is struggling to correctly assign protease and substrate sequences to the recombination output. What is the recommended workflow? The system uses a two-step sequencing approach to accurately link sequences to activity:

- Long-Read Sequencing (PacBio): Use this to separately sequence the TEVp and TEVs variant libraries, creating a lookup table that assigns each variant's actual amino acid sequence to its unique DNA barcode [28].

- Short-Read Sequencing (Illumina): Use this for the high-throughput activity reads. It sequences the barcodes for the protease and substrate, along with the recombination array state (flipped/unflipped) [28].

- Data Processing: In your analysis pipeline, replace the Illumina-read barcodes with the actual sequences from the PacBio lookup table. This reconstructs the full sequence-activity dataset for hundreds of thousands of pairs [28].

Q7: How can we use the generated data to find a protease with a completely new specificity profile? The collected sequence-activity data enables a machine learning (ML)-driven search of the vast sequence space. By training a deep learning model on your dataset of ~600,000 measured pairs, the model can learn the complex relationships between protease sequence and specificity. You can then use the trained model to predict the activity of millions of unseen protease sequences against your desired substrate profile, virtually screening for candidates with the optimal on- and off-target activities before synthesis and testing [28].

Quantitative System Performance

The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics from a typical large-scale experiment using the DNA-recorder system [28].

Table 1: DNA-Recorder System Performance Metrics

| Metric | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Variants Tested | 29,716 | Enables sampling of a large combinatorial sequence space. |

| Substrates Profiled | Up to 134 | Allows for comprehensive on- and off-target specificity profiling in a single experiment. |

| Protease-Substrate Pairs | ~600,000 | Generates a dataset of sufficient scale for training deep learning models. |

| Data Output | Fraction Flipped over time | Provides kinetic, quantitative activity measurements, not just binary hit identification. |

| Key Innovation | Epistasis-aware training set design | A sampling strategy that maximizes machine learning model accuracy for a given experimental effort. |

Essential Protocols

Protocol 1: DNA-Recorder Assembly and Library Construction

This protocol outlines the steps to create a plasmid library for protease specificity profiling.

- Vector Backbone: Use the established plasmid architecture containing the protease expression cassette, the Bxb1-SsrA fusion cassette, and the recombination array flanked by Bxb1 att sites [28].

- Library Cloning: Clone diversified protease and substrate variant libraries into their respective positions using Golden Gate, Gibson assembly, or traditional restriction-ligation cloning. The use of a visual (RFP) dropout marker can streamline the screening of recombinant clones [28] [30].

- Barcoding and Lookup Table Generation: Ensure each protease and substrate variant is associated with a unique DNA barcode. Perform long-read PacBio sequencing on the pooled library to create a lookup table matching barcodes to sequences [28].

- Transformation: Transform the library into your expression strain (e.g., E. coli) for the profiling experiment.

Protocol 2: Parallel Specificity Profiling and NGS Sample Preparation

This protocol details the experimental workflow for running the assay and preparing samples for sequencing.

- Culture and Induction: Inoculate and grow the E. coli library. Induce expression of the candidate proteases and the Bxb1 recombinase at the pre-optimized time [28].

- Time-Point Sampling: Collect samples at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 8 hours) post-induction to capture the kinetics of recombination.

- Plasmid Extraction: Isolate plasmids from each sample time point.

- PCR-Free Fragment Isolation: Isolate the target DNA fragment (containing the barcodes and recombination array) from the plasmids using a PCR-free protocol to avoid amplification bias [28].

- NGS Library Prep: Ligate Illumina sequencing adapters with sample-specific indices to the isolated fragments. Pool all samples for collective sequencing on an Illumina platform [28].

System Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the core operational and data processing workflows of the DNA-recorder system.

DNA-Recorder Mechanism

Specificity Profiling Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for DNA-Recorder Experiments

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-Recorder Plasmid | Genetic backbone for expressing protease and Bxb1-SsrA, and housing the recombination array. | Contains separate expression cassettes for the protease and Bxb1-SsrA; optimized promoters and RBS are critical [28]. |

| Bxb1 Recombinase | Phage integrase that catalyzes the inversion of the DNA recombination array upon stabilization. | Fused C-terminally to the substrate peptide and SsrA degradation tag [28]. |

| Protease Substrate Library | Peptide sequences inserted into the Bxb1-SsrA fusion that are cleaved by active proteases. | Includes the target substrate and numerous off-targets; flanking flexible linkers (e.g., GGSGG) improve performance [28]. |

| NGS Services/Reagents | For long-read (PacBio) barcode-to-sequence mapping and short-read (Illumina) activity readout. | Essential for deconvoluting the complex library data [28]. |

| Affinity Purification Resins | For purifying protease candidates or cleaved target proteins during validation. | Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins [16], Anti-Flag gel for Flag-tagged proteins [16]. |

| Tag Cleaving Proteases | For precision cleavage of affinity tags in protein purification workflows. | TEV Protease, HRV 3C Protease; available as recombinant enzymes [30] [16]. |

Machine Learning Approaches for Predicting Protease Substrate Specificity

Within protein purification workflows, unintended proteolysis is a significant and common problem that can compromise yield and integrity. Proteases, enzymes that cleave peptide bonds, are often present in cell lysates and can co-purify with the target protein, leading to its degradation. Accurately predicting protease substrate specificity is therefore not just a fundamental scientific question but a practical necessity for developing robust purification protocols. Traditional methods for characterizing protease activity are low-throughput and ill-suited for profiling the vast sequence space of potential substrates. This article explores how machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing the prediction of protease substrate specificity, providing tools that can be integrated into experimental design to safeguard protein purification.

Core Machine Learning Methodologies

Data Generation: The Foundation of ML Models

The accuracy of any ML model is contingent on the quality and scale of the data used for its training. Traditional datasets for protease specificity are often limited, but recent advances in high-throughput (HTP) experimental techniques are generating the comprehensive data required for powerful predictive models.

DNA Recorder for Specificity Profiling: A groundbreaking method involves using a DNA-based recorder to capture proteolytic activity within a living cell. This system links the cleavage of a specific substrate sequence to the activation of a recombinase enzyme, which in turn modifies a DNA array. The fraction of modified DNA arrays, quantifiable via next-generation sequencing (NGS), directly correlates with the proteolytic activity for a given protease-substrate pair. This approach allows for the parallel testing of tens of thousands of candidate proteases against hundreds of substrates, generating sequence-activity data for hundreds of thousands of protease-substrate combinations in a single experiment [28].

In Vitro Peptide Arrays: Another method utilizes chemically synthesized peptide arrays representing a vast swath of the proteome. These arrays are exposed to the enzyme of interest, and the modification sites are identified. The resulting data on which sequences are susceptible to enzymatic activity serves as a rich training set for ML models. This "ML-hybrid" approach, which starts with experimental generation of enzyme-specific training data, has been shown to mark a significant performance increase over traditional in vitro methods [31].

Machine Learning Algorithms and Tools

Once large-scale sequence-activity data is available, various ML models can be employed to predict specificity.

Epistasis-Aware Deep Learning: When engineering proteases, interactions between amino acids (epistasis) can profoundly influence function. Standard ML models can struggle with this complexity. "Epistasis-aware" training set design is a strategy that accounts for these non-additive effects, streamlining the search within enormous sequence spaces and strongly increasing model accuracy for a given experimental effort. This leads to data-efficient deep learning models that can accurately predict protease sequences with desired on- and off-target activities [28].

The EZSpecificity AI Tool: This publicly available tool demonstrates the power of combining expanded datasets with novel algorithms. EZSpecificity analyzes an enzyme's amino acid sequence to predict which substrate will best fit its active site. To overcome the limitation of scarce experimental data, its developers complemented existing data with millions of computational docking simulations, which provide atomic-level detail on how enzymes of various classes conform around different substrates. This model has been validated to achieve 91.7% accuracy in its top pairing predictions for certain enzyme classes, significantly outperforming previous models [32].

ML-Hybrid Ensemble Models: This approach involves creating a unique ML model for a specific enzyme. The model is trained on high-throughput in vitro data (e.g., from peptide arrays) and is often augmented with generalized PTM-specific predictions. This creates an ensemble model with enhanced predictive accuracy in cell models, capable of uncovering novel enzyme-substrate networks [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Featured ML Approaches for Specificity Prediction

| ML Approach | Key Feature | Reported Advantage | Primary Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recorder with Epistasis-Aware ML [28] | Accounts for non-additive amino acid interactions. | Increased data efficiency and model performance. | In vivo specificity profiling in E. coli. |

| EZSpecificity Tool [32] | Integrates enzyme sequence with docking simulation data. | 91.7% prediction accuracy in validation tests. | Experimental data & computational docking. |

| ML-Hybrid Ensemble [31] | Combines in vitro experimental data with computational models. | Important performance increase over conventional methods. | Peptide array screening. |

Experimental Protocols & Validation

Protocol: DNA Recorder for Protease Specificity Profiling

This protocol outlines the key steps for employing the DNA recorder system to generate data for ML model training [28].

- Plasmid Construction: Design a plasmid architecture containing:

- An expression cassette for the candidate protease (e.g., a library of TEVp variants).

- An expression cassette for a recombinase (e.g., Bxb1), fused to a C-terminal peptide containing the substrate sequence (e.g., TEVs) followed by a proteolytic degradation tag (SsrA).

- A recombination array DNA segment, flanked by the recombinase's attachment sites.

- Transformation and Culture: Transform the plasmid library into a suitable E. coli host strain. Grow the culture in shake flasks.

- Induction and Sampling: Induce expression of the recombinase. Draw samples from the culture at multiple time points post-induction.

- Plasmid Extraction and NGS Library Prep: Extract plasmids from each sample. Isolate the target DNA fragment containing the protease barcode, substrate barcode, and recombination array using a PCR-free protocol. Ligate Illumina sequencing adapters with sample-specific indices.

- Long-Read Sequencing for Barcode Mapping: Separately, use long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio) to determine the actual amino acid sequences of the protease and substrate variants linked to each DNA barcode, creating a lookup table.

- Data Processing and Analysis: Process the Illumina NGS data to obtain, for each protease-substrate pair:

- The protease and substrate sequences (by matching barcodes to the lookup table).

- The fraction of DNA arrays in the "flipped" state over time (the flipping curve).

- The proteolytic activity is derived from the kinetics of this flipping curve.

Protocol: In Vitro Validation of Predicted Substrates

After an ML model predicts novel substrates, these hits must be experimentally validated.

- Peptide Synthesis: Synthesize the peptide sequences identified by the ML model as potential substrates.

- In Vitro Cleavage Assay:

- Reaction Setup: Incubate the purified protease with the candidate peptide substrate in an appropriate reaction buffer.

- Reaction Control: Include a control with a catalytically inactive protease mutant (e.g., TEVp C151A) to account for non-specific effects [28].

- Time Course: Allow the reaction to proceed for a set duration or take multiple time-points.

- Analysis:

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze the reaction products by mass spectrometry to confirm the precise cleavage of the peptide bond at the predicted location [31].

- Other Analytical Methods: Alternatively, use HPLC or electrophoretic methods to separate and visualize cleavage products.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Protease and Protein Purification Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Product (from search results) |

|---|---|---|

| His-Tag Purification Resin | Affinity purification of recombinant His-tagged proteins. | HisSep Ni-NTA Agarose Resin [16] |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Added to lysis buffers to prevent proteolytic degradation of the target protein during extraction. | Pierce Protease Inhibitor Mini Tablets, EDTA-Free [20] |

| Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent | Gentle, detergent-based lysis of mammalian cells for protein extraction. | M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent [20] |

| Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktails | Preserves protein phosphorylation status by inhibiting phosphatases during extraction. | Pierce Phosphatase Inhibitor Mini Tablets [20] |

| Recombinant Proteases (e.g., Trypsin, Enterokinase) | Used for specific cleavage of fusion tags from purified proteins. | Recombinant Enterokinase (Tag Cleavage) [16] |

| Affinity Gels for Tagged Proteins | Immunoprecipitation or purification of specific tagged proteins (e.g., Flag, HA). | Anti-Flag Affinity Gel [16] |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Columns | Final polishing step in protein purification to separate proteins by size and remove aggregates. | Geldex 200 PG Chromatography Column [16] |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

FAQ 1: Our ML model for a novel protease has low predictive accuracy. What could be the issue?

- Cause: The most common cause is an insufficient or low-quality training dataset. If the training data is too small, lacks diversity, or has poor signal-to-noise, the model cannot learn the underlying rules of specificity.

- Solution: Prioritize generating high-quality, high-throughput data. Consider implementing a DNA recorder system [28] or peptide array screening [31] to profile a much larger number of protease-substrate combinations. Ensure your experimental readout (e.g., the flipping fraction in the DNA recorder) has a strong, quantifiable correlation with enzymatic activity.

FAQ 2: How can we assess and minimize off-target protease activity during protein purification?

- Cause: Promiscuous protease activity can lead to the degradation of non-target proteins, which is a critical concern for therapeutic applications [28].

- Solution: Integrate off-target activity directly into your ML screening process. The DNA recorder system, for instance, can test each protease variant against a large panel of potential off-target substrates simultaneously [28]. Furthermore, tools like EZSpecificity can be used to predict and screen for enzymes with high selectivity for your desired target over other structurally similar proteins [32]. Always include a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor cocktail in your lysis and purification buffers to stabilize your protein of interest [20].

FAQ 3: The purified protein is still being degraded despite using protease inhibitors. What steps should we take?

- Cause: The degradation could be due to an especially abundant or resilient protease that is not fully inhibited by the standard cocktail, or the inhibitors may not be effective against the specific protease class present.

- Solution:

- Re-optimize Buffers: Test different inhibitor cocktails (e.g., EDTA-free if your protein is metal-dependent) and ensure they are fresh and used at the correct concentration [20].

- Speed and Temperature: Perform all purification steps as quickly as possible and at 4°C to slow enzymatic activity.

- Identify the Culprit: Use ML-based specificity predictors to analyze your protein's sequence for potential cleavage sites [28] [32]. This can help you identify which class of protease might be responsible, allowing you to select a more tailored inhibitor.

- Shear Stress: Avoid vigorous pipetting, vortexing, or high-speed centrifugation, as shear stress can denature proteins and make them more susceptible to proteolysis [33].

Workflow Visualization

Targeted protein degradation using Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) represents a revolutionary approach in drug discovery and chemical biology. Unlike traditional small-molecule inhibitors that merely block protein activity, PROTACs mediate the complete removal of target proteins from cells by hijacking the cell's natural protein degradation machinery—the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) [34] [9]. These heterobifunctional molecules catalyze the degradation of select proteins of interest (POIs), offering advantages in targeting proteins previously considered "undruggable" and potentially overcoming drug resistance mechanisms [34] [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core components of a PROTAC molecule? A PROTAC consists of three essential elements: (1) a ligand that binds a protein of interest (POI), (2) a ligand for recruiting an E3 ubiquitin ligase (E3 recruiting element; E3RE), and (3) a linker connecting these two ligands [34] [35].

Q2: How do PROTACs achieve catalytic, sub-stoichiometric activity? After mediating target ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome, the PROTAC molecule is released and can be recycled to degrade additional POI copies. This "event-driven" pharmacology contrasts with the "occupancy-driven" model of traditional inhibitors, which require sustained target binding [34] [35].

Q3: What are the main advantages of PROTACs over conventional inhibitors? PROTACs can target proteins without deep binding pockets, eliminate both catalytic and scaffolding functions of a protein, operate catalytically at low doses, and potentially circumvent resistance mechanisms arising from target overexpression or mutations [34] [9].

Q4: Why is the choice of E3 ligase important in PROTAC design? While humans have over 600 E3 ligases, most current PROTACs recruit only a handful, primarily VHL and CRBN. The selection of E3 ligase influences degradation efficiency, selectivity, and potential on-target toxicities due to the degradation of natural E3 substrates [36] [35].

Q5: What is the "Hook effect"? At high concentrations, a PROTAC may saturate its binding sites on the POI and E3 ligase independently, forming non-productive binary complexes instead of the productive POI-PROTAC-E3 ternary complex. This leads to a paradoxical decrease in degradation efficiency [35].

Troubleshooting Common PROTAC Experiments

Issue 1: Lack of Target Protein Degradation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Confirm E3 Ligase Engagement: Verify that your PROTAC can effectively bind the intended E3 ligase. Use competitive binding assays or cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) to confirm engagement [36].

- Verify Proteasome Dependence: Treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132). If degradation is blocked, the process is proteasome-dependent, as expected. Lack of blockade suggests an off-mechanism [36].

- Check Ternary Complex Formation: The PROTAC must facilitate a productive interaction between the POI and E3 ligase. Use techniques like co-immunoprecipitation to detect ternary complex formation [35].

- Investigate Ubiquitination: Implement ubiquitination assays to check if the POI is being polyubiquitinated, particularly with K48-linked chains which are a primary signal for proteasomal degradation [37] [9].

Issue 2: Off-Target Degradation or Effects

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Evaluate Ligand Selectivity: The warhead (POI ligand) might have unknown off-target binding. Profile warhead selectivity across the proteome where possible [34].

- Assess E3 Ligase Substrate Interference: E3 ligases like CRBN have native substrates (e.g., IKZF1/3, GSPT1). Your PROTAC may inadvertently promote their degradation, causing off-target effects. Monitor levels of these common substrates [36].

- Optimize for Selective Ternary Complex Formation: PROTACs can achieve selectivity even with promiscuous warheads by forming productive ternary complexes only with specific POIs. Screen various E3RE and linker combinations to exploit cooperative interactions [34] [35].

Issue 3: High Degradation Concentrations (Poor Potency)

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Optimize Linker Length and Composition: The linker is critical for optimal geometry. Systematically vary linker length and chemistry (flexible PEG, alkyl, rigid rings) to find the most potent configuration [34] [35].

- Explore Different E3 Ligases: If degradation with one E3 ligase recruiter (e.g., CRBN) is weak, try recruiting an alternative E3 (e.g., VHL). Degradation efficiency is cell-type and POI-dependent [34] [35].

- Utilize Lower Affinity Warheads: High-affinity POI binding is not always necessary for efficient degradation. Even weak binders or ligands that lack inhibitory activity can be effective in a PROTAC context due to positive cooperativity in the ternary complex [34].

Issue 4: Hook Effect Observed in Dose-Response

Solution: This is an expected characteristic of the PROTAC mechanism. Carefully map the full dose-response curve and identify the optimal concentration range that precedes the hook effect. Use this concentration for subsequent experiments [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Assays

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for PROTAC Development and Validation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| E3 Ligase Ligands | Recruit E3 ubiquitin ligase to form ternary complex. | Thalidomide, Lenalidomide, Pomalidomide (for CRBN); VHL ligand analogs [34] [9]. |

| PROteasome Inhibitors | Confirm proteasome-dependent degradation mechanism. | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib [36] [38]. |

| Neddylation Inhibitor | Blocks CRBN activity by inhibiting cullin neddylation. | MLN4924 [36]. |

| Tag-Targeted Degraders | Pre-validate target degradability before designing a PROTAC (e.g., dTAG, HaloTAG, BromoTAG systems) [35]. | |

| Ubiquitin Variants (UbVs) | High-affinity, specific inhibitors of Ub-binding domains; useful as mechanistic probes [39]. |

Table 2: Critical Assays for Characterizing PROTAC Activity

| Assay | Parameter Measured | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Western Blotting | Target protein level reduction (DC₅₀, Dmax) [35]. | Standard method; can be low-throughput. |

| Cellular Viability Assays | Functional consequence of degradation (IC₅₀) [36]. | e.g., CellTiter-Glo. |

| Ternary Complex Assays | Formation and stability of POI:PROTAC:E3 complex. | e.g., Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC) [35]. |

| Ubiquitination Assay | Detection of ubiquitin chains on the POI. | Can use tagged ubiquitin (e.g., HA-Ub) followed by immunoprecipitation of the POI and Western blot for the tag [9]. |

Experimental Workflows and Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the core mechanisms and a generalized experimental workflow for PROTAC development and testing.

PROTAC Mechanism of Action

PROTAC Development Workflow

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: A Primer

PROTACs function by co-opting the native ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). The UPS is the primary mechanism for controlled intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotes [38] [9]. It involves a cascade of enzymatic reactions:

- Activation: A ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner.

- Conjugation: The ubiquitin is transferred to a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2).

- Ligation: A ubiquitin ligase (E3) recognizes a specific substrate and facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the target protein.

- Polyubiquitination: The process repeats, building a polyubiquitin chain on the substrate. K48-linked polyubiquitin chains are the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation [9].

- Degradation: The polyubiquitinated protein is recognized and unfolded by the 26S proteasome, and its peptide fragments are released for recycling [38].

PROTACs act as a bridge, bringing an E3 ubiquitin ligase into proximity with a POI that it would not normally recognize, thereby leading to the POI's ubiquitination and destruction [34].

Clinical Landscape of PROTAC Therapies

Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) represent a paradigm shift in drug discovery, moving beyond traditional inhibition to actively degrade disease-causing proteins through the ubiquitin-proteasome system [26]. This technology has unlocked therapeutic possibilities for previously "undruggable" targets, including transcription factors, mutant oncoproteins, and scaffolding proteins [26]. As of 2025, no PROTAC therapy has received full market approval, but the field has progressed rapidly, with the first New Drug Application submitted to the FDA [26] [40].

PROTACs in Active Clinical Development

The following table summarizes key PROTAC candidates currently in clinical trials, highlighting their targets, indications, and development status [27].

Table 1: Selected PROTAC Degraders in Clinical Trials (2025 Update)

| Drug Candidate | Company/Sponsor | Target | Indication(s) | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vepdegestran (ARV-471) | Arvinas/Pfizer | Estrogen Receptor (ER) | ER+/HER2- Breast Cancer | Phase III |

| CC-94676 (BMS-986365) | Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) | Androgen Receptor (AR) | Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (mCRPC) | Phase III |

| BGB-16673 | BeiGene | Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) | Relapsed/Refractory B-cell Malignancies | Phase III |

| ARV-110 | Arvinas | Androgen Receptor (AR) | mCRPC | Phase II |

| KT-474 (SAR444656) | Kymera Therapeutics | IRAK4 | Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Atopic Dermatitis | Phase II |

| ASP-3082 | Astellas | KRAS G12D | Solid Tumors | Phase I |

| DT-2216 | Dialectic Therapeutics | BCL-XL | Liquid and Solid Tumors | Phase I |

| NX-2127 | Nurix | BTK, IKZF1/3 | Relapsed/Refractory B-cell Malignancies | Phase I |

Highlights from Advanced-Stage Clinical Programs

- Vepdegestran (ARV-471): This oral ER-targeting degrader is the most advanced PROTAC in development. In the Phase III VERITAC-2 trial, it demonstrated a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) compared to fulvestrant in patients with ESR1-mutated advanced or metastatic breast cancer. A New Drug Application is currently under FDA review [27] [40].