A Comprehensive Guide to Quality Assessment for Membrane Protein Preparations: From Bench to Validation

High-quality membrane protein preparations are fundamental to structural biology, functional studies, and drug discovery, with membrane proteins constituting over 60% of pharmaceutical targets.

A Comprehensive Guide to Quality Assessment for Membrane Protein Preparations: From Bench to Validation

Abstract

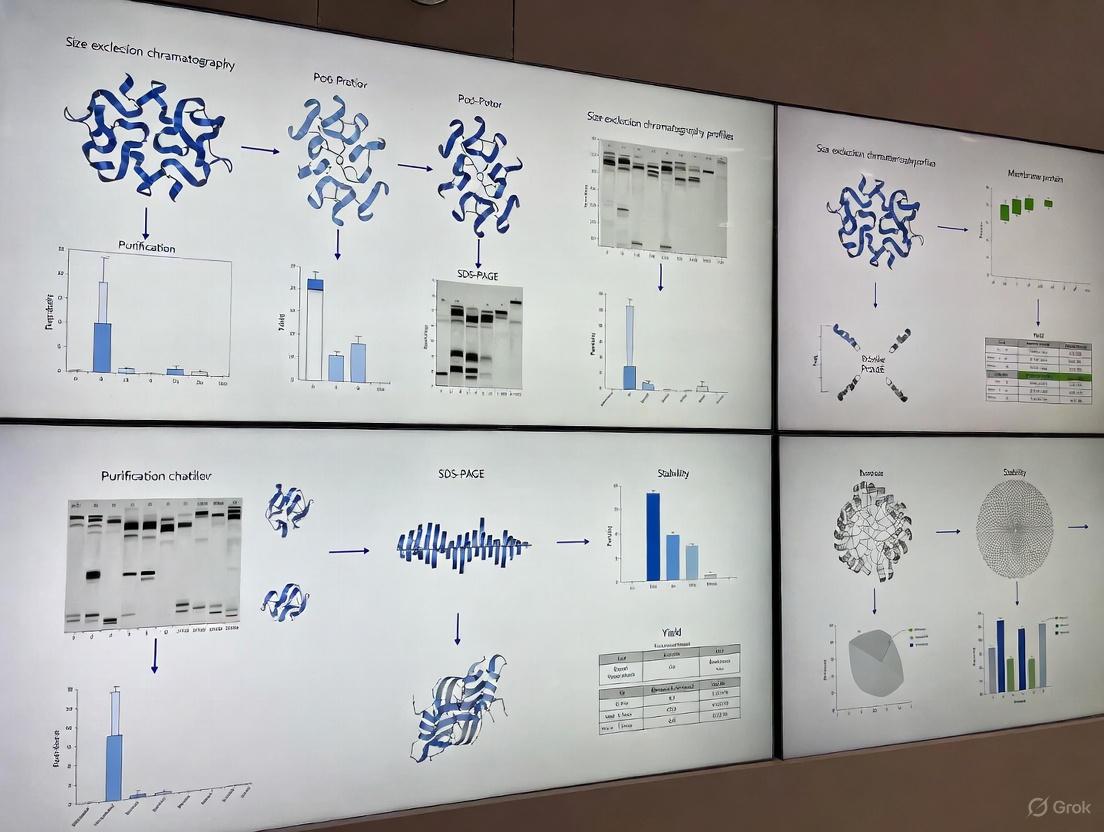

High-quality membrane protein preparations are fundamental to structural biology, functional studies, and drug discovery, with membrane proteins constituting over 60% of pharmaceutical targets. This article provides a systematic framework for the quality assessment of membrane protein preparations, addressing critical needs from foundational principles to advanced validation. It explores the biochemical and biophysical rationales behind quality control, details established and emerging methodological workflows for stability and function analysis, offers troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls like aggregation and instability, and outlines rigorous validation techniques to ensure data reliability. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices to empower robust and reproducible membrane protein research.

Why Quality Matters: The Critical Role of Membrane Proteins in Health, Disease, and Drug Discovery

Membrane proteins are fundamental biological molecules embedded within cellular lipid bilayers. They are responsible for critical functions including signal transduction, molecular transport, and cell-to-cell communication. Their strategic location and diverse roles make them prime targets for therapeutic intervention; approximately 60% of current drugs target membrane proteins, with G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) alone accounting for about 27% of drugs on the market [1] [2]. Furthermore, their involvement in disease pathways positions them as valuable biomarkers for diagnosis and monitoring. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to assist researchers in overcoming common challenges in membrane protein research, framed within the context of quality assessment for membrane protein preparations.

Troubleshooting FAQs

My membrane protein expresses poorly or not at all in a heterologous system. What should I check?

Poor expression is a common hurdle, often related to host cell toxicity, protein instability, or incorrect folding.

- Solution: Optimize Your Expression System

- Verify Vector and Sequence: Confirm your cloned sequence is correct and in-frame. Check for long stretches of rare codons that can cause truncation; use online tools for analysis and consider using host strains engineered to express rare tRNAs [3] [4].

- Change Your Competent Cells: Avoid standard BL21(DE3) cells for toxic proteins. Use specialized strains like C41(DE3), C43(DE3), or Lemo21(DE3), which have reduced background expression and gentler induction [5] [4]. For T7 systems, use strains expressing T7 lysozyme (e.g., pLysS or lysY) to suppress basal T7 polymerase activity [3] [4].

- Adjust Growth Conditions: Run an expression time course. Test different induction temperatures (e.g., 15-30°C) and inducer concentrations. Using a minimal growth medium (e.g., M9) can reduce the cell growth rate and improve the folding of some membrane proteins [5] [3].

- Consider a Solubility Tag: Fuse your target protein to a solubility tag like superfolder GFP or maltose-binding protein (MBP) to improve stability and expression yields [5] [4].

How can I extract my membrane protein while maintaining its stability and function?

The extraction process, which removes the protein from its native lipid environment, is a critical point where instability occurs.

- Solution: Choose and Optimize Your Solubilizing Agent

- Screen Detergents Systematically: Detergents are the most common solubilizing agents, but they can disrupt protein structure. Screen a variety of detergents (e.g., DDM, OG, Triton X-100) to find the optimal one. Use a concentration approximately 100x the detergent's Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) [5]. Modern techniques like Flow-Induced Dispersion Analysis (FIDA) can screen multiple detergents rapidly with minimal sample volume [6].

- Use Membrane-Mimetic Systems: For functional studies, consider extracting with nanodiscs or lipid polymers. These systems engulf entire sections of the cell membrane, preserving the native lipid environment and oligomeric state of the protein, which is crucial for accurate functional assays [5] [7].

- Optimize Extraction Parameters: Allow sufficient time for extraction (3 hours to overnight) and perform it at a slightly elevated temperature (20-30°C) to increase efficiency, provided it does not harm your sample [5].

My membrane protein is insoluble or aggregates after purification. What can I do?

Aggregation often results from protein misfolding or the loss of structure-stabilizing lipids during extraction and purification.

- Solution: Stabilize the Protein Structure

- Re-evaluate Detergents: The detergent may be too harsh. Re-screen detergents or try mixtures with cholesterol homologs (CHS) to mimic the fluidity of native membranes [7].

- Use Chaperones and Lipids: Add lipids or chaperones to the purification buffer to assist with folding and stability [7]. For proteins requiring disulfide bonds, consider using engineered strains like SHuffle that facilitate correct bond formation in the cytoplasm [4].

- Lower Purification Temperature: Perform all purification steps at 4°C to slow down denaturation and aggregation [5].

- Reintegrate into a Lipid Bilayer: If using detergents for extraction, reintegrating the purified protein into artificial bilayer systems like nanodiscs can restore a more native environment and functionality [7] [6].

My protein binds poorly to the affinity chromatography column. How can I improve binding?

Low binding efficiency can be caused by the solubilizing agent masking the affinity tag or the tag being inaccessible.

- Solution: Enhance Tag Accessibility

- Use a Loose Resin: Instead of a static column, use loose affinity resin (e.g., loose Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins) and mix it physically with your sample for several hours to encourage binding [5].

- Dilute Your Sample: Dilute the protein sample at least 2-fold to reduce the concentration of the solubilizing agent (detergent), which can act as a crowding agent and hide the affinity tag [5].

- Adjust the Affinity Tag: If the tag is buried, consider moving it to the opposite terminus of the protein or lengthening it (e.g., from 6xHis to 12xHis) [5].

- Change the Resin Metal: For His-tagged proteins, charging the resin with cobalt instead of nickel can increase purity, though it may reduce recovery [5].

Experimental Protocols for Quality Assessment

Protocol 1: Detergent Screening for Membrane Protein Solubilization

Objective: To rapidly identify the optimal detergent for solubilizing a membrane protein while maintaining its stability and monodispersity.

Materials:

- Purified membrane fraction containing your target protein.

- Detergent stock solutions (e.g., n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside/DDM, Lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol/LMNG, Octyl glucoside/OG, Triton X-100).

- Solubilization buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0).

- Thermonixer or water bath.

- Ultracentrifuge.

- SDS-PAGE equipment or FIDA instrument [6].

Method:

- Prepare Membrane Fraction: Isolate the membrane fraction from your expression host via cell lysis and differential centrifugation.

- Set Up Reactions: Aliquot the membrane fraction into multiple tubes. Add a different detergent to each tube at a concentration of 1-2% (w/v). Include a no-detergent control.

- Solubilize: Incubate the mixtures with gentle agitation for 3 hours at 4°C or 20°C.

- Separate: Ultracentrifuge the samples at high speed (e.g., 100,000 x g) for 30 minutes to pellet insoluble material.

- Analyze:

- Collect the supernatant (solubilized fraction) and analyze by SDS-PAGE to determine solubilization efficiency.

- For advanced analysis, use FIDA or dynamic light scattering (DLS) to measure the hydrodynamic radius and polydispersity of the solubilized protein, identifying conditions that yield a homogeneous, monodisperse population [6].

Protocol 2: Functional Characterization of a GPCR in Nanodiscs via Ligand Binding

Objective: To measure the binding affinity of a small molecule ligand to a GPCR reconstituted in nanodiscs under native-like conditions.

Materials:

- Purified GPCR in nanodiscs.

- Fluorescently labelled or unlabeled ligand.

- Binding assay buffer.

- FIDA instrument or Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) system [6].

Method:

- Reconstitute GPCR: Incorporate the purified GPCR into nanodiscs following established protocols to create a disc-like phospholipid bilayer encircled by a membrane scaffold protein.

- Prepare Ligand Dilutions: Create a dilution series of the ligand in the assay buffer.

- Measure Binding:

- Using FIDA: Mix the GPCR-nanodisc sample with each ligand concentration. FIDA measures the change in the hydrodynamic radius of the protein-ligand complex directly in solution, without the need for purification or immobilization. The shift in size is used to calculate binding affinity [6].

- Using SPR: Immobilize the GPCR-nanodisc on a sensor chip. Inject the ligand over the surface and monitor the binding response in real-time to determine kinetics and affinity.

- Data Analysis: Fit the binding data to an appropriate model (e.g., Langmuir isotherm) to determine the dissociation constant (Kd).

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Membrane Protein Research

| Reagent Type | Example Products | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Cell Lines | C41(DE3), C43(DE3), Lemo21(DE3), SHuffle T7 | Reduces basal expression for toxic proteins; promotes disulfide bond formation. [5] [4] |

| Detergents | n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM), Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) | Extracts proteins from the lipid bilayer; forms micelles around the protein. [5] |

| Membrane Mimetics | Nanodiscs, Liposomes | Provides a native-like lipid environment for structural and functional studies. [5] [6] |

| Affinity Chromatography Resins | Ni-NTA (Nickel/Nickel-Cobalt), Cobalt-Chelating Resins | Purifies recombinant proteins via affinity tags (e.g., His-tag). Cobalt can offer higher purity. [5] |

| Solubility Tags | MBP (Maltose-Binding Protein), superfolder GFP, Lysozyme tags | Enhances protein solubility and expression yields; allows tracking via fluorescence. [5] [4] |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, EDTA-free cocktails | Prevents proteolytic degradation of target proteins during extraction and purification. [3] |

Table 2: Key Quantitative Data on Membrane Proteins and Assessment Tools

| Metric | Value or Statistic | Context & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Market Share of Drugs | ~60% of drugs target membrane proteins [2]. | Highlights their immense pharmaceutical importance. |

| GPCR Drug Target Share | ~27% of all drugs target GPCRs [1]. | Underscores the dominance of one membrane protein family in pharmacology. |

| PDB Representation | <1% of PDB structures are membrane proteins [1]. | Explains the difficulty in computational modeling due to lack of templates. |

| IQ Scoring Function Success Rate | 93-100% in selecting native-like models [1]. | Demonstrates the high accuracy of dedicated model quality assessment programs. |

| HPMScore Performance | 46.9% success rate for Top 1 model selection [2]. | Outperformed DOPE (40.1%) in recognizing high-quality structural models. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram: KRAS Inhibitor Mechanism

Diagram: Membrane Protein Research Workflow

Technical FAQs: Core Stability Challenges and Mechanisms

FAQ 1: Why are membrane proteins inherently unstable outside of their native lipid bilayer?

Membrane proteins are unstable in aqueous solutions because their large hydrophobic transmembrane domains, which are normally stabilized by the lipid bilayer's hydrophobic core, become exposed to water. This exposure is energetically unfavorable and drives protein aggregation or denaturation [8] [9]. The detergent micelles used to solubilize them often provide a poor mimic of the native membrane, lacking its specific chemical and physical properties, which can lead to irreversible inactivation [8] [10] [11].

FAQ 2: What is the primary mechanism behind detergent-induced instability?

The instability mechanism often involves the disruption of vital protein-lipid interactions. When extracted with detergents, structure-stabilizing annular lipids can be stripped away from the protein surface [7]. Furthermore, the detergent micelle itself may not adequately accommodate the protein's transmembrane domains, leading to conformational stress and eventual inactivation, as seen in studies of diacylglycerol kinase [9].

FAQ 3: How does the lipid composition of the membrane influence protein stability?

Lipids regulate membrane proteins through a dynamic process called preferential lipid solvation [11]. The protein's surface, which can be geometrically and chemically irregular, is solvated by a fluid layer of lipid molecules. The lipid composition determines the solvation energetics for different protein conformational states. Even minor changes in lipid composition can shift the conformational equilibrium of a protein, thereby influencing its stability and functional activity [11].

FAQ 4: What are the key amino acid factors that influence membrane protein stability?

Stability is influenced by interactions between transmembrane domains. Strategic point mutations within these domains can significantly improve stability [8] [9]. Statistical analyses show that extremostable proteins often have a higher abundance of small nonpolar amino acids like Gly, Val, and Ala in their core, promoting tight packing [12]. Additionally, a significant number of salt bridges on the protein surface can contribute to stability under extreme conditions [12].

Troubleshooting Guides: From Expression to Purification

Troubleshooting Low Expression Yields

Problem: Poor expression levels of the target membrane protein.

Solutions:

- Change Expression Host: Avoid standard BL21(DE3) E. coli for toxic proteins. Use specialized strains like C41(DE3), C43(DE3), or Lemo21(DE3) that reduce transcription rates or allow tunable expression, improving cell health and yield [5] [13].

- Use a Minimal Growth Medium: Counterintuitively, using non-rich media like M9 minimal medium can reduce the cell growth rate, minimizing peptide folding errors in the membrane and potentially improving yields [5].

- Express Homologs: If your target protein does not express well, consider expressing a homologous gene from another species. Subtle differences in the primary sequence can lead to significant improvements in protein stability and expression [5].

- Control Basal Expression: For T7-based systems, use host strains that co-express T7 lysozyme (e.g., pLysS or lysY strains) to inhibit T7 RNA polymerase and prevent toxic basal expression before induction [13].

Troubleshooting Instability During Extraction and Solubilization

Problem: The protein loses activity or aggregates upon extraction from the membrane.

Solutions:

- Systematic Detergent Screening: Identify optimal detergents using high-throughput screens. Classify detergents as "mild" (e.g., non-ionic) or "harsh" (e.g., ionic) and screen for those that maintain stability and functionality [8]. The detergent should be present at a concentration approximately 100 times its Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) [5].

- Use Lipid-Based Mimics: Replace or supplement detergents with systems that better preserve the native lipid environment:

- Nanodiscs: Engulf membrane sections with native lipids using membrane scaffold proteins [5] [10].

- Peptidiscs: Utilize a short amphipathic bi-helical peptide (NSPr) to wrap around and shield the membrane-exposed part of the protein without requiring additional lipids [10].

- Amphipols: Use polymeric amphiphiles that can stabilize membrane proteins in detergent-free solutions [10].

- Optimize Extraction Conditions: Allow ample time for extraction (3 hours to overnight) and perform it at a slightly elevated temperature (20–30°C) to increase efficiency, provided it does not harm the sample [5].

- Add Stabilizing Ligands: Include substrates, inhibitors, or agonists during purification. Antibodies or nanobodies can also be used to bind and stabilize specific conformational states [8].

Troubleshooting Protein Loss During Purification

Problem: The protein does not bind to affinity columns or is lost during further purification.

Solutions:

- Use Loose Resin: For nickel-affinity chromatography, use loose resin that can be physically mixed with the sample for several hours to encourage binding, as affinity tags can be hidden by large solubilizing agents [5].

- Dilute the Solubilizing Agent: Dilute your sample at least 2-fold to reduce the crowding caused by detergents or other solubilizing agents, giving the affinity tag better access to the resin [5].

- Adjust the Affinity Tag: If binding remains poor, consider moving the affinity tag to the opposite terminus of the protein or lengthening it (e.g., from 6xHis to 12xHis) to push it away from the protein surface [5].

- Improve Purity with Cobalt Resin: For impure samples, charge your affinity resin with cobalt instead of nickel. Cobalt has fewer oxidation states and can increase purity, albeit sometimes at the cost of sample recovery [5].

Quantitative Data and Reagent Solutions

Membrane Protein Stabilization Agents

Table 1: Key Reagent Solutions for Membrane Protein Stabilization

| Reagent / Method | Key Function | Advantages & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Detergents (e.g., DDM) | Solubilizes membrane proteins by forming micelles. | Essential for initial extraction; can be destabilizing. Requires screening [8] [5]. |

| Nanodiscs | Stabilizes proteins in a patch of native lipid bilayer surrounded by scaffold proteins. | Preserves native environment; good for functional assays. Can be large and complex to assemble [5] [10]. |

| Peptidisc (NSPr peptide) | Short amphipathic peptide wraps around the transmembrane domain. | "One-size-fits-all", detergent-free, rapid, no added lipids required [10]. |

| Amphipols | Polymeric amphiphiles that stabilize proteins in aqueous solution. | Detergent-free alternative. Can be useful for specific downstream applications [10]. |

| Stabilizing Mutations | Point mutations in transmembrane domains to enhance stability. | Can be identified via alanine scanning or consensus mutagenesis. Requires screening [8] [9]. |

| Ligands / Nanobodies | Bind to and stabilize specific functional conformations of the protein. | Can confer high stability and conformational homogeneity [8]. |

Stoichiometry of the Peptidisc Stabilization Method

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of the MalFGK2 Peptidisc Complex

| Component | Stoichiometry per MalFGK2 Complex | Method of Determination |

|---|---|---|

| NSPr Peptide | 10 ± 2 peptides | SDS-PAGE [10] |

| Annular Lipids | 41 ± 10 lipids | Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) [10] |

| Total Mass | 251 ± 12 kDa | Calculation from above [10] |

| Total Mass | 247 ± 24 kDa | Native Mass Spectrometry [10] |

| Total Mass | 250 ± 17 kDa | SEC-MALS [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Stability Assessment

Protocol: High-Throughput Detergent Screening Using FSEC

Purpose: To rapidly identify the optimal detergent for solubilizing and stabilizing a membrane protein.

Method:

- Create Construct: Express the target membrane protein as a fusion with a C-terminal GFP tag [8] [5].

- Solubilize: In a high-throughput format (e.g., 96-well plate), solubilize membranes containing the fusion protein with a library of different detergents.

- Clarify: Centrifuge the solubilized mixtures to remove insoluble material.

- Analyze by FSEC: Inject the supernatant onto a size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) column coupled with a fluorescence detector (excited by GFP fluorescence).

- Evaluate: A sharp, symmetric peak indicates a monodisperse, stable protein. Broad or multiple peaks suggest aggregation or heterogeneity [8] [5].

Protocol: Thermostability Assay for Mutant Screening

Purpose: To screen libraries of mutant membrane proteins for variants with enhanced stability.

Method:

- Create Mutant Library: Generate a library of mutants via random or site-directed mutagenesis [8] [9].

- Express and Solubilize: Express the mutants, pellet the cells, and solubilize the membranes in a chosen detergent.

- Heat Challenge: Aliquot the solubilized samples. Incubate one aliquot at an elevated temperature for a set time, while keeping a control aliquot on ice.

- Assay Activity: Measure the remaining functional activity (e.g., enzymatic activity, ligand binding) in both heated and control samples.

- Identify Stabilizing Mutants: Clones that retain a higher percentage of activity after heating are considered more stable and are selected for further study [9].

Stability Mechanisms and Workflow Visualizations

Membrane Protein Instability Pathway

Membrane Protein Stabilization Workflow

Why is Quality Assessment for Membrane Proteins Crucial?

Membrane proteins are fundamental to cellular life, acting as gatekeepers, signal transducers, and molecular transporters. They represent over 60% of current drug targets, making their study paramount in biomedical research and drug development [14] [15]. However, their inherent instability outside the native lipid bilayer environment makes quality assessment a critical, non-negotiable step in any experimental workflow. Unlike soluble proteins, membrane proteins require a multifaceted approach to quality control that confirms not just purity, but also structural integrity and function [16] [15]. A preparation of high quality is one that is pure, monodisperse, in its native conformation, and functionally active.

Core Quality Metrics and Their Assessment

A robust quality control pipeline for membrane proteins relies on several interconnected metrics. The table below summarizes the key parameters and the primary methods used to evaluate them.

Table 1: Essential Quality Metrics for Membrane Protein Preparations

| Quality Metric | Description | Primary Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Purity | The proportion of the target protein in the sample relative to contaminants. | SDS-PAGE, Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), Mass Spectrometry [5] [17] |

| Monodispersity & Homogeneity | The uniform distribution of a single protein species in solution, without aggregation. | Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Analytical Ultracentrifugation [5] |

| Native Conformation & Oligomeric State | The correct folding and assembly of the protein, including its quaternary structure. | Native Mass Spectrometry (nMS), Size-Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS), X-ray Crystallography, Cryo-EM [17] [16] |

| Functional Integrity | The protein's ability to perform its biological activity (e.g., bind ligands, transport ions). | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Thermal Shift Assays (TSA), Enzymatic or Transport Assays [15] |

| Lipid/Detergent Environment | The composition and properties of the membrane mimetic surrounding the protein. | Native Mass Spectrometry (nMS), Fluorescence Spectroscopy [17] [11] |

Troubleshooting Common Issues in Membrane Protein Preparation

FAQ 1: My membrane protein is not expressing, or the yield is very low. What can I do?

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Toxicity to Host Cells: Membrane protein overexpression can be toxic to standard expression systems like E. coli BL21.

- Solution: Switch to specialized competent cell strains such as C41(DE3) or C43(DE3), which have mutations that reduce protein expression rates, making them more tolerant of toxic membrane proteins [5].

- Poor Folding in the Membrane:

- Solution: Use a minimal growth medium (e.g., M9), which can slow the cell growth rate and reduce peptide folding errors in the membrane [5].

- Inefficient Extraction from the Membrane: The choice of solubilizing agent is critical.

- Solution: Optimize the detergent used for extraction. Ensure it is present at a concentration of approximately 100x its Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC). Allow sufficient time for extraction (3 hours to overnight) at a slightly elevated temperature (20-30°C) to increase efficiency [5].

FAQ 2: My protein is aggregating during purification. How can I improve monodispersity?

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Loss of Native Lipid Environment: Removing the protein from its native membrane can expose hydrophobic surfaces, leading to aggregation.

- Solution: Use membrane mimetics that better preserve the native lipid environment. Consider switching from traditional detergents to nanodiscs or amphipols, which can engulf entire sections of the cell membrane along with the protein, preserving its native oligomerization state and preventing aggregation [5] [17].

- Harsh Buffer Conditions:

- Solution: Optimize buffer conditions by including stabilizing additives such as glycerol, lipids, or reducing agents to prevent degradation and aggregation [18].

- Sample Heterogeneity: Heterogeneous samples can lead to broad peaks in chromatography and poor results in downstream applications.

- Solution: Implement additional chromatography steps, such as ion exchange, or optimize existing ones. For affinity purification with a His-tag, using a loose resin and mixing for several hours can improve binding. Diluting the sample to reduce the concentration of the solubilizing agent can also help the affinity tag access the resin [5] [17].

FAQ 3: How can I confirm my purified membrane protein is correctly folded and functional?

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Lack of Functional Assays:

- Solution: Implement biophysical and functional assays.

- Thermal Shift Assays (TSA) can probe stability by measuring the protein's melting temperature (( T_m )), which often increases when a ligand is bound [15].

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) can directly measure real-time binding kinetics with ligands or other proteins, confirming functional integrity [15].

- Native Mass Spectrometry (nMS) is a powerful tool for determining the intact molecular mass, oligomeric state, and even identifying bound lipids or small molecules under non-denaturing conditions [17].

- Solution: Implement biophysical and functional assays.

- Incorrect Oligomeric State:

- Solution: Use Size-Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS) to accurately determine the absolute molecular weight and oligomeric state in solution. Note that the hydrodynamic radius of a membrane protein in detergent is not a reliable indicator of its molecular weight due to the large, variably shaped detergent micelle [5].

FAQ 4: My purification resin isn't binding my protein effectively. What's wrong?

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Affinity Tag is Inaccessible: The solubilizing detergent or the protein's own structure can hide the affinity tag.

- Solution: Dilute your sample at least 2-fold to reduce the crowding effect of the solubilizing agent. If using a His-tag, consider lengthening the tag (e.g., from 6xHis to 12xHis) or moving it to the opposite terminus of the protein [5].

- Solution: For nickel-affinity chromatography, use a loose resin that can be physically mixed with the sample for several hours rather than a static column, allowing better access to the tag [5].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Monodispersity and Oligomeric State by Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

- Column Equilibration: Equilibrate your SEC column with at least two column volumes of your purification or storage buffer, ensuring the detergent is present above its CMC.

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge your protein sample at high speed (e.g., 15,000 x g) for 10 minutes to remove any insoluble aggregates.

- Sample Injection: Inject a concentrated, small volume of your protein (typically 50-500 µL) onto the column.

- Chromatography: Run the chromatography at a slow, constant flow rate (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mL/min for an analytical column) to ensure proper separation.

- Analysis: Monitor the elution at 280 nm. A sharp, symmetric peak is indicative of a monodisperse sample. A broad or multiple peaks suggest heterogeneity or aggregation [5].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SEC

| Reagent | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| SEC Buffer | Maintains protein stability and detergent micelle integrity during separation. | 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% DDM. |

| Detergent | Solubilizes the protein and prevents aggregation. | DDM, LMNG; keep above CMC [5]. |

| SEC Column | Separates protein complexes based on hydrodynamic radius. | Superdex 200 Increase, ENrich 650. |

Protocol 2: Evaluating Thermal Stability by Thermal Shift Assay (TSA)

- Sample Setup: In a real-time PCR tube, mix your membrane protein with a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange, CPM) that binds to exposed hydrophobic patches.

- Thermal Ramp: Place the tube in a real-time PCR instrument and gradually increase the temperature (e.g., from 25°C to 95°C at a rate of 1°C/min).

- Fluorescence Monitoring: The instrument monitors the fluorescence signal. As the protein unfolds, hydrophobic regions are exposed, allowing the dye to bind and increasing fluorescence.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence against temperature. The midpoint of the transition curve (( Tm )) is the melting temperature. A higher ( Tm ) indicates a more stable protein. Ligand binding often stabilizes the protein, resulting in a shift to a higher ( T_m ) [15].

Protocol 3: Confirming Native Conformation and Ligand Binding via Native Mass Spectrometry (nMS)

- Sample Preparation: The membrane protein must be in a volatile buffer compatible with MS (e.g., ammonium acetate) and solubilized in a detergent that facilitates gentle ionization, such as fluorinated surfactants or amphipols [17].

- Ionization: The sample is introduced into the mass spectrometer via Electrospray Ionization (ESI), which gently transfers the protein from solution to the gas phase while preserving non-covalent interactions [17].

- Mass Analysis: The mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios of the ions are determined using high-resolution mass analyzers like Time-of-Flight (TOF) or Orbitrap systems [17].

- Data Interpretation: The resulting spectrum allows for the direct determination of the protein's oligomeric state and molecular mass. The binding of lipids, drugs, or other ligands can be observed as a mass increase, confirming functional interactions in a native-like state [17].

Quality Assessment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a comprehensive quality assessment of a membrane protein preparation, from initial purification to functional validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Materials for Membrane Protein Quality Control

| Category | Reagent / Tool | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane Mimetics | DDM (n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside), LMNG (Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol) | Mild detergents for solubilizing and stabilizing membrane proteins [5]. |

| Nanodiscs, Amphipols | Lipid-based systems that provide a more native-like environment than detergents [5] [17]. | |

| Stabilizing Additives | Glycerol, Lipids, Reducing Agents (DTT) | Prevent aggregation, maintain reducing environment, and enhance stability [18]. |

| Chromatography Resins | Nickel-NTA Resin (Loose) | Affinity purification of His-tagged proteins; loose resin allows better tag access [5]. |

| Cobalt-based Resin | Alternative to nickel for higher purity, though with potentially lower yield [5]. | |

| Analytical Tools | SYPRO Orange / CPM Dye | Fluorescent dyes for Thermal Shift Assays to measure protein stability [15]. |

| Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) / SPR Chips | Sensors for label-free analysis of binding kinetics and affinity [15]. |

Membrane proteins are essential for numerous cellular processes, including signal transduction, transport, and cell communication. However, their structural and functional integrity is highly dependent on the native lipid membrane environment. Removing these proteins from their natural context often leads to loss of activity and stability, presenting significant challenges for in vitro studies. Understanding lipid-protein interactions is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental prerequisite for obtaining high-quality, functional membrane protein preparations for research and drug development. This technical support center addresses the most common experimental issues arising from disruptions to the native membrane environment, providing troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols to help researchers maintain protein stability and function throughout their experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why does my membrane protein lose activity after purification?

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Disruption of the native lipid solvation environment.

- Solution: Incorporate native lipids or lipid analogs during purification. Studies show that lipid solvation enhances protein stability by facilitating residue burial in the protein interior, a phenomenon reminiscent of the lipophobic effect [19]. Consider using nanodiscs or styrene-maleic acid (SMA) copolymers that preserve native lipid annuli instead of detergents alone [20].

Cause: Removal of specific regulatory lipids.

- Solution: Identify and supplement with crucial lipid species. Research on the CLC-ec1 antiporter demonstrates that lipid composition influences dimerization equilibrium not through specific long-lived lipid binding sites, but via preferential lipid solvation, where certain lipids become enriched at the protein interface due to solvation energetics [11]. Even minor changes in lipid composition (e.g., adding <1% short-chain lipids) can profoundly impact thermodynamic stability [11].

Cause: Destabilization of the cooperative residue-interaction network.

- Solution: Optimize the hydrophobic thickness of your membrane-mimetic system. The lipid bilayer strengthens the cooperative network of membrane proteins. Using amphiphilic assemblies that match the native membrane's hydrophobic thickness and packing strength is critical for stability [19].

FAQ 2: How does lipid composition specifically affect my membrane protein's function?

Lipid composition can alter membrane protein function through multiple, distinct mechanisms, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Mechanisms of Lipid Regulation of Membrane Proteins

| Mechanism | Description | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Preferential Lipid Solvation | Dynamic enrichment of specific lipid types at the protein surface alters the conformational equilibrium based on solvation energetics, without long-lived binding [11]. | CLC-ec1 dimerization is inhibited by short-chain DL lipids even at <1% concentration; no saturation effect is observed, ruling out classic binding [11]. |

| Global Bilayer Properties | Changes in bulk membrane properties (thickness, lateral pressure, curvature) couple to protein conformational changes [21]. | Gramicidin A channel lifetime and conductance report on changes in bilayer properties induced by amphitropic proteins like tubulin [21]. |

| Lipid-Mediated Cooperativity | Lipid solvation enhances internal residue interactions, strengthening the protein's cooperative network and its response to stimuli [19]. | Both α-helical and β-barrel membrane proteins from E. coli show increased stability and strengthened residue-interaction networks in lipid bilayers compared to detergents [19]. |

| Competitive Protein-Lipid vs. Protein-Protein Interactions | Strong protein-lipid interactions can compete with and disrupt protein-protein interactions essential for function [22]. | Simulations of RGG protein condensation on membranes show that highly charged lipids can dissolve condensates by outcompeting protein-protein interactions [22]. |

FAQ 3: My membrane protein shows abnormal oligomerization in my assay. Could lipids be the cause?

Yes, this is a common issue. The oligomeric state of membrane proteins is particularly sensitive to the lipid environment.

- Investigate Preferential Solvation: As demonstrated with CLC-ec1, the exposed interface of a monomer can create a local membrane defect (e.g., thinning). Lipids that better solvate this defect (e.g., shorter-chain lipids) will become enriched there, altering the dimerization free energy [11]. Monitor your protein's oligomeric state (e.g., via analytical SEC or native PAGE) in membranes of varying lipid composition.

- Check for a Balance of Interactions: If your protein undergoes liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) or clustering on membranes, remember that a delicate balance exists. While some protein-lipid interaction promotes membrane binding and condensation, excessively strong protein-lipid interactions can compete with the protein-protein interactions that drive condensation, leading to dispersion [22].

- Protocol: Assessing Oligomerization State in Different Lipid Compositions

- Reconstitute your purified protein into liposomes or nanodiscs of defined composition. For example, compare a neutral PC lipid (e.g., POPC) with a system containing a fraction of anionic lipids (e.g., POPG) or short-chain lipids (e.g., DLPC) [11] [22].

- Incubate the proteoliposomes at the desired temperature (e.g., 20-30°C can be more efficient than 4°C) for a sufficient time to reach equilibrium (≥3 hours, overnight is often better) [5].

- Analyze the oligomeric state using a technique like Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) or Fluorescence Cross-Correlation Spectroscopy (FCCS). Note that SEC of membrane proteins requires caution as the detergent/lipid micelle adds significant, variable mass [5].

- Interpret results: A shift in the oligomeric equilibrium (e.g., from dimer to monomer) upon changing lipid composition indicates strong lipid regulation, likely through preferential solvation [11].

FAQ 4: How can I identify which specific lipids are important for my protein's stability?

- Use Native Nanodiscs or SMA Lipid Particles (SMALPs): These technologies allow for the extraction of a membrane protein along with a "shell" of its native surrounding lipids. Subsequent analysis by mass spectrometry can identify the co-purifying lipid species, which are strong candidates for being functionally important [20].

- Employ Computational Analysis: Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, particularly coarse-grained MD (CGMD), can predict lipid interactions and enrichment around your protein. This method was used to reveal the sequestration of short-chain DL lipids at the dimerization interface of CLC-ec1 monomers [11].

- Perform Equilibrium Titration Studies: To distinguish between specific lipid binding and weak solvation effects, perform activity or stability assays while systematically titrating in a specific lipid. A lack of saturation in the effect (a linear response) is a key signature of a weak linkage effect like preferential solvation, as opposed to specific, saturable binding [11].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Quantitative Analysis of Lipid Transport and Its Impact on Protein Environment

Understanding how specific lipid species move between organelles is key to comprehending the dynamic lipid environment of membrane proteins. The following workflow, based on a recent quantitative imaging study, allows for mapping lipid flux [23].

Title: Lipid Transport and Metabolism Analysis Workflow

Detailed Methodology:

- Probe Loading: Load bifunctional lipid probes (containing diazirine and alkyne modifications) into the plasma membrane of live cells (e.g., U2OS) via a brief (0.5-4 min) pulse of α-methyl-cyclodextrin-mediated exchange from donor liposomes. This incorporates lipid molecules into the outer leaflet without compromising PM integrity [23].

- Chase and Metabolism: Remove the loading solution and incubate cells at 37°C for various time points (0 min to 24 h) to allow for intracellular transport and metabolic conversion.

- Crosslinking and Staining: At each time point, photo-crosslink lipids to interacting proteins using UV irradiation, fix cells, and remove non-crosslinked lipids. Fluorescently label the crosslinked bifunctional lipids via click chemistry [23].

- Quantitative Imaging: Acquire confocal images and generate segmented probability maps for organelles (PM, Golgi, ER, endosomes, mitochondria) using pixel classifier software (e.g., Ilastik). Partition the lipid signal between organelles based on these maps [23].

- Mass Spectrometry: In parallel, perform quantitative shotgun lipidomics using ultra-high-resolution Fourier-Transform Mass Spectrometry (FT MS) to track the metabolic conversion of the bifunctional probes at each time point. The mass difference from the diazirine group allows distinction from native lipids [23].

- Kinetic Modeling: Fit the imaging and MS data to a kinetic model that disentangles vesicular and non-vesicular transport routes, yielding rate constants for the interorganelle flux of specific lipid species [23].

Troubleshooting Notes:

- High Background: Ensure thorough removal of non-crosslinked lipids after UV irradiation.

- Poor Signal: Optimize the concentration of bifunctional lipids and the efficiency of the click chemistry reaction.

- This protocol reveals that non-vesicular transport is up to 11 times faster than vesicular transport and is the primary mechanism for fast, species-selective lipid sorting, directly impacting the lipid environment of membrane proteins [23].

Protocol: Discriminating Between Specific Lipid Binding and Preferential Solvation

A critical step in quality assessment is determining the mechanism of lipid regulation. The following protocol outlines a thermodynamic approach to distinguish between these mechanisms [11].

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Lipid Regulation Mechanisms

| Feature | Specific Lipid Binding | Preferential Lipid Solvation |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Model | Lipid as a ligand | Lipid as a solvent component |

| Saturation | Yes, follows a binding isotherm | No, effect does not saturate |

| Lifespan of Interaction | Long-lived, specific | Dynamic, transient |

| Key Experimental Test | Titrate lipid and look for saturable effect on protein function/stability. | Titrate lipid and look for non-saturating, linear-like effect on dimerization constant or conformational equilibrium. |

Experimental Steps:

- Reconstitute the membrane protein of interest (e.g., CLC-ec1) into a reference lipid bilayer (e.g., POPC).

- Measure the functional or structural equilibrium parameter of interest (e.g., dimerization constant, activity) in the reference membrane. Use a technique like single-molecule fluorescence or analytical ultracentrifugation.

- Titrate the lipid species under investigation (e.g., DLPC) into the reference membrane at increasing mol% concentrations, starting from very low levels (<1%).

- Measure the functional/structural parameter at each concentration point.

- Analyze the linkage: Plot the change in the equilibrium parameter (e.g., ΔG of dimerization) against the mol% of the titrated lipid.

- A saturating binding curve suggests specific lipid binding at a defined site.

- A non-saturating, near-linear response (observed even at very low concentrations) is characteristic of preferential solvation [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying Lipid-Protein Interactions

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nanodiscs / SMALPs | Membrane-mimetic systems that solubilize proteins while preserving a more native-like lipid bilayer environment than detergents. Ideal for functional studies and identifying native co-purifying lipids [20]. | Choose scaffold protein size (for nanodiscs) to match protein diameter. SMALPs extract proteins with native lipids but can have pH/salt limitations. |

| Bifunctional Lipid Probes | Minimally modified lipids (e.g., with diazirine and alkyne) used to track lipid transport and localization in cells via fluorescence microscopy and MS [23]. | Confirm that modifications do not alter the lipid's native membrane properties (e.g., phase behavior). |

| Coarse-Grained (CG) Force Fields (e.g., Martini) | Enables microsecond-to-millisecond timescale Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations of proteins in complex lipid membranes to study lipid dynamics and enrichment [11] [22]. | Requires conversion from all-atom structures. Martini 3 offers improved accuracy. Simulation timescales are accelerated compared to all-atom. |

| C41(DE3) / C43(DE3) E. coli Cells | Bacterial expression strains with mutated promoters for gentler, slower expression of membrane proteins, reducing toxicity and improving yields of functional protein [5]. | Superior to standard BL21(DE3) for toxic membrane proteins. Lemo21(DE3) is another option for fine-tuning expression. |

| Loose Affinity Resin (e.g., Ni-NTA) | For purifying His-tagged membrane proteins. Loose resin allows for constant mixing, improving access of the often-buried affinity tag to the resin. | Static columns often yield poor binding. If loose resin is unavailable, use a peristaltic pump for closed-loop recirculation over the column [5]. |

| Gramicidin A (grA) | A small channel-forming peptide used as a sensitive reporter of its lipid environment. Changes in grA channel lifetime and conductance report on global and local membrane properties, respectively [21]. | Ideal for studying how amphitropic proteins or other perturbations alter bilayer properties (elastic modulus, curvature, charge). |

The Assessment Toolkit: Biophysical and Functional Methods for Profiling Membrane Protein Preparations

Integral membrane proteins (IMPs) are crucial therapeutic targets, representing nearly two-thirds of all druggable targets due to their roles in signal transduction, cell recognition, and transport processes. However, their inherent hydrophobicity and complex lipid interactions present significant challenges for structural and functional studies. The fundamental step in these investigations involves extracting proteins from their native lipid environment and stabilizing them in aqueous solution using membrane mimetics. These mimetics range from traditional detergents to advanced detergent-free systems that better preserve native protein structure and function. Selecting the appropriate mimetic is therefore critical for successful outcomes in downstream applications such as structural biology, biophysical characterization, and drug discovery. This guide provides a systematic framework for this selection process and troubleshooting common experimental hurdles.

Research Reagent Solutions: A Toolkit for Membrane Protein Studies

The following table summarizes key reagents used in membrane protein solubilization and stabilization, highlighting their primary functions and characteristics.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Membrane Protein Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Detergents | DDM, LMNG, GDN, BOG [24] | Solubilize proteins by forming micelles around hydrophobic regions | Mild detergents (e.g., DDM) preserve stability; harsher ones (e.g., SDS) cause denaturation [24] |

| Membrane Scaffold Proteins (MSPs) | ApoA-I-based MSPs [25] [24] | Form Nanodiscs by encircling a lipid bilayer patch | Provides a more native lipid environment; requires detergent for initial extraction [24] |

| Amphipathic Polymers | SMA, DIBMA [26] [24] | Directly solubilize membranes to form native Nanodiscs (e.g., SMALPs) | Detergent-free extraction; preserves native lipids and local membrane environment [26] |

| Amphipathic Peptides | Peptidisc, DeFrMSPs [27] [25] | Stabilize membrane proteins in water-soluble complexes | "One-size-fits-all" property; compatible with mass spectrometry; enables detergent-free workflows [27] |

| Computational Design Tools | AF2seq, ProteinMPNN [28] | Design soluble analogues of membrane protein folds | Creates stable, soluble versions of complex membrane topologies like GPCRs [28] |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs and Solutions

FAQ 1: My membrane protein loses activity after detergent solubilization. What are my options?

Issue: Detergents can strip essential lipids or disrupt protein complexes, leading to loss of function [25] [24].

Solutions:

- Switch to a Milder Detergent: If using a harsh detergent, switch to milder alternatives like Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) or Glycodiosgenin (GDN), which are known to better preserve the stability and function of many membrane proteins [24].

- Use a Detergent-Free System: Transition to a polymer- or peptide-based mimetic that retains native lipids.

- SMALP/DIBMA: Styrene-maleic acid (SMA) or diisobutylene-maleic acid (DIBMA) copolymers can directly solubilize proteins and lipids from the membrane into native nanodiscs, preserving the local lipid environment [26] [24].

- Peptidisc/DeFrMSPs: Use amphipathic peptides like Peptidisc or DeFrMSPs for detergent-free reconstitution. This has been shown to maintain functional states of sensitive transporters, such as the MalFGK2 ABC transporter, whose ATPase activity is uncoupled in detergents but remains coupled in peptide-based nanodiscs [27] [25].

FAQ 2: My protein is solubilized but aggregates during purification or on the Cryo-EM grid. How can I prevent this?

Issue: Aggregation can occur due to protein instability, exposure of hydrophobic surfaces, or unsuitable buffer conditions.

Solutions:

- Screen Scaffolding Agents: Incorporate a screening step with different scaffolding agents to find the optimal one for your protein.

- Peptide Screening: As demonstrated with DeFrMSPs, screen a panel of amphipathic peptides with different modifications (e.g., fatty acid conjugations) to find the condition that yields monodisperse particles [25].

- Polymer Screening: A large library of different polymers may be required for optimal ND reconstitution, as their performance can be protein-specific [25].

- Optimize the Lipid Environment: Use nanodisc systems (MSP-based or polymer-based) that provide a lipid bilayer shield, which can protect hydrophobic surfaces and prevent aggregation [24].

- Assess Sample Quality Early: Implement Fluorescent Size Exclusion Chromatography (FSEC) to rapidly analyze sample quality and monodispersity using only small quantities of sample before committing to large-scale purification [29].

FAQ 3: My target is a large or dynamic membrane protein complex that falls apart in detergents. What strategies can I use?

Issue: Large, multi-subunit complexes are often destabilized by detergents, which can dissociate subunits.

Solutions:

- Bypass Detergents Entirely: Employ a direct, detergent-free extraction method.

- DeFrND Protocol: Use the DeFrND (detergent-free reconstitution into native nanodiscs) method with engineered membrane scaffold peptides (DeFrMSPs) to directly pull the intact complex from the native membrane, preserving its stoichiometry and integrity [25].

- Consider a Computational Approach: For some applications, consider the novel approach of computationally designing a soluble analogue of your membrane protein target. Deep learning pipelines (e.g., AF2seq-MPNN) can now design stable, soluble proteins that recapitulate the complex topologies of IMPs like GPCRs and rhomboid proteases, potentially bypassing handling challenges altogether [28].

FAQ 4: How can I systematically select the best detergent or mimetic for a new membrane protein?

Issue: The optimal mimetic is highly protein-specific, and a rational screening approach is needed.

Solution: Implement a tiered screening workflow.

Diagram 1: A tiered mimetic screening workflow for systematic optimization.

Experimental Protocol for a Mimetic Screen:

- Solubilization Test: Create small-scale aliquots of membrane preparation. Solubilize each with a different detergent (e.g., DDM, LMNG) or polymer (e.g., SMA) at a concentration slightly above its CMC for 1-2 hours on ice.

- Ultracentrifugation: Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 100,000 × g) to separate solubilized protein (supernatant) from insoluble material (pellet).

- Analysis: Analyze the supernatant and pellet by SDS-PAGE to determine solubilization efficiency.

- Stability Assessment: For successful solubilizing conditions, proceed with FSEC [29] to check for aggregation and a functional assay to confirm activity is retained.

FAQ 5: How do I stabilize a membrane protein for Thermal Shift Assay or Thermal Proteome Profiling (TPP)?

Issue: Standard TPP protocols are often incompatible with detergents and have poor coverage of the membrane proteome [27].

Solution: Adopt a detergent-free membrane mimetic strategy specifically designed for stability assays.

Protocol: Membrane-Mimetic Thermal Proteome Profiling (MM-TPP) [27]

- Prepare a Membrane Proteome Library: Solubilize a membrane fraction with a mild detergent and then reconstitute it into a Peptidisc library. This replaces the detergent and stabilizes the membrane proteome in a water-soluble, native-like state.

- Ligand Treatment: Divide the Peptidisc library into two aliquots. Incubate one with the ligand of interest and the other with a vehicle control (e.g., ddH₂O).

- Heat Denaturation: Subject the samples to a range of elevated temperatures (e.g., 3 minutes at each temperature) to induce protein denaturation and precipitation.

- Separation and Analysis: Remove precipitated protein by ultracentrifugation. Analyze the soluble fraction (containing thermally stabilized proteins) by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Data Analysis: Identify proteins that show a significant shift in thermal stability in the ligand-treated sample compared to the control, as these are high-probability ligand binders.

Diagram 2: The MM-TPP workflow for profiling membrane protein-ligand interactions.

Comparative Analysis of Membrane Mimetic Technologies

The table below provides a structured comparison of the primary mimetic technologies to guide the selection process.

Table 2: Comparison of Membrane Mimetic Technologies

| Technology | Mechanism of Action | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Detergents (e.g., DDM, LMNG) | Forms micelles around protein transmembrane domains [24] | Well-established, wide commercial availability, easy to use [24] | Can denature proteins, strip native lipids, disrupt protein complexes [25] [24] | Initial solubilization, proteins stable in micelles |

| MSP Nanodiscs | Membrane scaffold protein encircles a lipid bilayer patch [24] | Provides a more native lipid environment, high stability [24] | Requires detergent for initial extraction, costly, requires optimization [24] | Biophysical studies, functional assays requiring a lipid bilayer |

| Polymer-Based Native Nanodiscs (e.g., SMALP) | Amphipathic polymer directly solubilizes membrane patches [26] [24] | Detergent-free, preserves native lipids and complex integrity [24] | Sensitivity to divalent cations, may require polymer screening, limited Cryo-EM use [25] [24] | Studying proteins in a near-native lipid environment, detergent-sensitive complexes |

| Peptide-Based Systems (e.g., Peptidisc, DeFrND) | Amphipathic peptides form a protective belt around the protein [27] [25] | Detergent-free, "one-size-fits-all" stability, MS-compatible, can maintain functional coupling [27] [25] | Peptide optimization may be needed for some targets, relatively new technology | Thermal shift assays (MM-TPP), functional studies, proteome-wide screens [27] |

| Computational Soluble Analogues | Deep-learning design of soluble versions of IMP folds [28] | Completely bypasses membrane handling, high stability [28] | Not the native protein, may not capture all functional aspects, cutting-edge method [28] | Drug discovery on novel epitopes, fundamental protein design research [28] |

Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC) is a first-principles, solution-based technique that plays a critical role in the biophysical characterization of macromolecules, including challenging membrane protein preparations. For researchers investigating membrane protein quality, AUC provides unmatched capabilities for determining molecular weight, assessing sample purity, and quantifying states of aggregation—all without requiring a solid matrix or labeling that could disrupt the native state of the protein. Unlike techniques such as size exclusion chromatography (SEC) that involve stationary phases and potential disruptive interactions, AUC allows membrane proteins to be analyzed in their true solution environment, even in the presence of detergents and lipids necessary for stability [30] [31]. This technical support center provides comprehensive guidance for implementing AUC in your membrane protein research, addressing common challenges through detailed protocols, troubleshooting advice, and expert recommendations.

For membrane protein scientists, AUC serves as an essential orthogonal method to validate results obtained from other techniques. Its ability to directly quantify soluble aggregates—a critical quality attribute for therapeutic proteins—makes it invaluable for pre-formulation studies and stability assessments [30]. Furthermore, AUC's broad dynamic range, capable of analyzing particles from kilodaltons to gigadaltons and concentrations from picomolar to millimolar, ensures its relevance across diverse experimental setups from initial membrane protein characterization to advanced interaction studies [31].

Key Principles and Methodologies

Fundamental Concepts

AUC operates on two fundamental physical principles: sedimentation under centrifugal force and the relationship between sedimentation behavior and macromolecular properties as described by the Svedberg equation:

[ s = \frac{M(1-\overline{v}ρ)}{N_A f} ]

where (s) is the sedimentation coefficient, (M) is molecular weight, (\overline{v}) is the partial specific volume, (ρ) is solvent density, (N_A) is Avogadro's number, and (f) is the frictional coefficient [31]. This equation establishes the direct relationship between observable sedimentation and molecular properties, allowing researchers to extract accurate molecular parameters without external standards.

Operational Modes

AUC offers two primary operational modes, each with distinct advantages for membrane protein characterization:

Sedimentation Velocity (SV-AUC) applies high centrifugal forces to observe the rate at which molecules migrate through solution. This mode is particularly valuable for assessing sample heterogeneity, detecting aggregates, studying conformational changes, and determining hydrodynamic properties [32] [33]. The sedimentation coefficient (measured in Svedbergs, S) provides information about both molecular size and shape.

Sedimentation Equilibrium (SE-AUC) operates at lower speeds where sedimentation and diffusion forces balance, creating a stable concentration gradient. This method enables precise determination of absolute molecular weight, study of reversible interactions, and thermodynamic characterization of self-associating systems [32] [33].

Table: Comparison of AUC Operational Modes for Membrane Protein Research

| Parameter | Sedimentation Velocity (SV-AUC) | Sedimentation Equilibrium (SE-AUC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Applications | Size distribution analysis, aggregate detection, sample heterogeneity, conformational studies | Molecular weight determination, binding constants, stoichiometry of interactions |

| Experimental Speed | High speeds (40,000-60,000 rpm) | Lower speeds (10,000-25,000 rpm) |

| Experimental Duration | Several hours | Several hours to days |

| Data Output | Sedimentation coefficient distribution | Molecular weight and association constants |

| Information Content | Hydrodynamic properties, sample purity, aggregation state | Thermodynamic parameters, equilibrium constants |

| Ideal for Membrane Protein Studies | Assessing detergent-solubilized protein homogeneity, detecting aggregated species | Determining oligomeric state in detergent solutions |

Essential Reagents and Materials

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful AUC experiments require careful preparation and selection of appropriate reagents. The following table outlines essential materials for membrane protein AUC studies:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Membrane Protein AUC Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Appropriate Buffer System | Maintains protein stability and native conformation | Must be compatible with detergents; should match reference buffer for interference optics [30] |

| Detergents | Solubilizes and stabilizes membrane proteins | Critical for maintaining solubility; choice affects partial specific volume and density calculations [34] |

| Density Modifiers | Adjusts solvent density for optimal sedimentation | Glycerol, sucrose, or D₂O may be used; requires precise measurement of resulting solvent density [30] |

| Reference Buffer | Matches solvent environment for interference optics | Must be dialyzed against sample buffer when using interference detection [33] |

| Absorbance Standards | Verifies optical system performance | Needed for quantitative concentration measurements at specific wavelengths |

Experimental Design and Protocols

Sample Preparation Protocol

Proper sample preparation is crucial for obtaining reliable AUC data, particularly for sensitive membrane protein systems:

Sample Purity and Characterization: Begin with the purest membrane protein preparation achievable. Prior characterization using complementary methods such as fluorescent size exclusion chromatography (FSEC) can provide initial quality assessment and save valuable AUC instrument time [35] [29].

Buffer Matching and Dialysis: For interference detection, carefully dialyze the membrane protein sample against the reference buffer to minimize signal from buffer mismatches [30] [33]. For absorbance detection, SEC buffer exchange may be sufficient.

Concentration Optimization: Target an absorbance of approximately 1.0 for absorbance-based detection to ensure optimal signal-to-noise ratio while maintaining linear detector response [30]. For membrane proteins with low extinction coefficients, consider using interference detection.

Density and Viscosity Measurements: Precisely measure or calculate solvent density and viscosity, as these parameters significantly impact sedimentation coefficient calculations. This is particularly important for detergent-containing buffers, which may have different physical properties than aqueous solutions.

Control for Co-sedimenting Solutes: When formulating with sugars or polyols that may form density gradients during centrifugation, include control experiments in sugar-free buffers or apply appropriate inhomogeneous solvent models during data analysis [30].

Basic SV-AUC Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in a sedimentation velocity experiment for membrane protein characterization:

Basic SV-AUC Experimental Workflow

Data Collection Parameters

For membrane protein studies using SV-AUC, implement the following data collection protocol:

Rotor Selection: Use an An-Ti50 rotor or equivalent suitable for the required speeds and sample volumes.

Temperature Control: Set temperature to 20°C for standard experiments, or adjust based on membrane protein stability requirements.

Speed Selection: Program rotor speed between 40,000-60,000 rpm depending on the expected size of the membrane protein complex and detergent micelle.

Data Acquisition: Collect absorbance (230-280 nm) and/or interference data at 2-3 minute intervals throughout the run duration.

Radial Resolution: Set radial step size to 0.003 cm for high-resolution data collection.

Run Duration: Continue centrifugation until complete clearance of the meniscus is observed for all sedimenting species.

Troubleshooting Common AUC Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our membrane protein preparation shows significant aggregation in SV-AUC but not in SEC. Which result should we trust?

A1: SV-AUC is generally more reliable for aggregate detection since it occurs in solution without a stationary phase that can potentially trap or dissociate aggregates [30]. SEC can sometimes dissociate weakly associated aggregates through dilution effects or interactions with the column matrix. The absence of a solid matrix in AUC makes it less prone to such artifacts. We recommend trusting the AUC results and investigating buffer conditions that might improve monodispersity.

Q2: How do we account for the contribution of detergent micelles to the sedimentation of our membrane protein?

A2: The detergent contribution presents a common challenge in membrane protein AUC. Several approaches can help:

- Characterize the detergent alone under identical buffer conditions to determine its sedimentation coefficient.

- Consider using contrast matching through density modulation, though this is challenging with conventional detergents.

- Analyze the protein-detergent complex as a single entity and interpret the resulting molecular weight accordingly.

- In some cases, using minimal detergent concentrations while maintaining solubility can reduce this complication.

Q3: Why do we get different aggregation percentages between AUC and SEC methods?

A3: Discrepancies often arise from fundamental methodological differences [30]:

- SEC may dissociate aggregates during separation or through dilution effects.

- AUC measures all material in the sample, while SEC may miss extremely large aggregates that are excluded from column pores.

- Interactions with the SEC stationary phase can retain certain species.

- Always consider AUC as the more accurate measure for solution-state aggregation.

Q4: What are the key considerations for selecting between absorbance and interference detection?

A4: The choice depends on your specific application:

- Use absorbance detection when working with purified membrane proteins at appropriate concentrations (A280 ~0.1-1.0).

- Interference detection is preferable for samples with low extinction coefficients or when using detergents that absorb in the UV range.

- For complex detergent systems, interference detection often provides better signal-to-noise.

- Remember that interference detection requires careful buffer matching through dialysis.

Q5: How can we improve the resolution between monomeric and dimeric species of our membrane protein?

A5: Several strategies can enhance resolution:

- Optimize rotor speed - slightly lower speeds may improve separation of closely sedimenting species.

- Ensure optimal sample concentration to minimize concentration-dependent association.

- Extend data collection time to improve boundary separation.

- Consider using SE-AUC for precise molecular weight determination of each species.

- Explore buffer modifications (pH, salt) that might alter the association equilibrium.

Advanced Applications in Membrane Protein Research

Specialized Methodologies

AUC offers several advanced applications particularly valuable for membrane protein research:

Ligand-Induced Conformational Changes: By comparing sedimentation coefficients in the presence and absence of ligands, researchers can detect ligand-induced conformational changes in membrane proteins. Such changes often alter hydrodynamic properties detectable by SV-AUC [32].

Detergent Optimization Studies: SV-AUC serves as a powerful tool for screening detergents and stabilization conditions for membrane proteins. The method can rapidly identify conditions that minimize aggregation and improve monodispersity [34].

Complex Stoichiometry Determinations: SE-AUC can accurately determine the stoichiometry of membrane protein complexes, even in mixed detergent-lipid systems, providing critical information about functional assemblies.

Stability Assessment: Through thermal or chemical challenge experiments monitored by AUC, researchers can assess the stability of membrane protein preparations under different solution conditions.

Data Analysis and Interpretation Framework

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for analyzing and interpreting AUC data from membrane protein experiments:

AUC Data Analysis Decision Framework

Analytical Ultracentrifugation remains an indispensable tool in the membrane protein researcher's toolkit, providing critical information about molecular weight, purity, and aggregation state that is difficult to obtain through other methods. Its solution-based, matrix-free nature makes it particularly valuable for studying delicate membrane protein systems that may be affected by surfaces or matrices in other techniques.

As the field advances, developments in AUC instrumentation and software are moving the technique toward compliance with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) environments, expanding its utility from basic research to pharmaceutical development and quality control [36]. The implementation of fluorescence detection systems has further extended AUC's capabilities to study increasingly complex systems at lower concentrations [31].

For membrane protein scientists, AUC provides the rigorous hydrodynamic characterization necessary to advance our understanding of structure-function relationships in this biologically crucial class of proteins. By following the protocols and troubleshooting guidance outlined in this technical support document, researchers can leverage the full power of AUC to overcome common challenges in membrane protein characterization and accelerate their research progress.

FAQs: Core Principles and Applications

Q1: What is the key advantage of adding MALS to a standard SEC setup for membrane protein analysis? SEC-MALS determines the absolute molecular mass of a protein complex in solution independently of its elution volume. This is crucial for membrane proteins, which often bind detergent micelles. While SEC alone separates by hydrodynamic size, MALS allows you to distinguish the mass of the protein oligomer from the mass of the associated detergent, providing the true oligomeric state and confirming sample homogeneity [37].

Q2: Why is my light scattering baseline high and noisy, especially after installing a new column? This is a common issue. Light scattering detectors are extremely sensitive to large particles and aggregates, including nanometer-sized particles and fines that can bleed from the column packing material. These contaminants are often too small to be trapped by column frits and can cause a persistently high baseline and noise. This is particularly problematic for low-angle light scattering measurements and aqueous mobile phases [37].

Q3: How can I tell if my SEC-MALS system is clean enough for sensitive analysis? A clean system shows a stable, low-noise baseline on both the concentration detector (RI or UV) and the light scattering detector. If the concentration detector baseline is stable but the light scattering signal shows high background or drift, the system—often the column itself—is likely the source of contamination and requires cleaning or replacement with an LS-certified column [37].

Q4: My membrane protein tends to aggregate. What techniques can I use alongside SEC-MALS to assess homogeneity? SEC-MALS is an excellent primary tool, but homogeneity can be confirmed using orthogonal techniques:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Rapidly assesses the size distribution and monodispersity of a sample in solution, directly detecting aggregates [38] [39].

- Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC): Provides detailed information on molecular weight, oligomeric state, and conformation through sedimentation behavior [39].

- 05SAR-PAGE: A specialized electrophoresis method effective for resolving membrane protein oligomers and complexes without disrupting weak interactions [40].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common SEC-MALS Issues and Solutions

| Symptom | Possible Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High LS baseline & noise | Contaminants from new column [37] | Flush column extensively per manufacturer's instructions; use columns pre-treated for LS [37] |

| Particulates in mobile phase or sample [37] | Filter all solvents through 0.1 µm filters; centrifuge or filter samples before injection [37] | |

| Broad/Asymmetric Peaks | Column overloading [41] | Reduce injection volume or sample concentration [41] |

| Non-specific interaction with column [42] | Adjust mobile phase (e.g., add salt); use a different column chemistry [42] | |

| Aggregated protein sample | Optimize buffer conditions; include stabilizing additives | |

| Unexpectedly High Molecular Mass | Protein aggregation [39] | Check for homogeneity with DLS; use fresh sample; optimize buffer [38] [39] |

| Low LS Signal | Sample mass or concentration too low [37] | Increase sample concentration; ensure dn/dc value is correct |

| Peak Tailing | Secondary interactions with column [42] | Modify mobile phase pH or ionic strength; use a shield-phase column [42] |

| Pressure Fluctuations/High Pressure | Column blockage [41] [42] | Reverse-flush column if possible; replace guard column; filter samples [41] [42] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Membrane Protein Oligomerization and Homogeneity by SEC-MALS

Objective: To determine the absolute molecular mass and oligomeric state of a purified membrane protein in solution.

Materials:

- Purified membrane protein in a compatible buffer.

- SEC column (e.g., silica- or polymer-based) appropriate for the protein's size.

- SEC-MALS system (comprising HPLC, SEC column, MALS detector, and RI detector).

- Degassed, filtered running buffer (e.g., with detergent to maintain solubility).

Method:

- System Equilibration: Equilibrate the entire SEC-MALS system with the running buffer until stable baselines are achieved on both the RI and LS detectors [37].

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge the protein sample at high speed (e.g., 15,000 x g) to remove any large aggregates or particles. Use the same running buffer for the sample [37].

- Injection and Separation: Inject the clarified protein sample onto the SEC column. Typical injection volumes range from 10-100 µL, depending on column size.

- Data Collection: The eluent passes sequentially through the MALS detector and then the RI detector. Data is collected for both detectors.

- Data Analysis: Using the ASTRA or similar software:

- The RI detector provides the concentration of the sample.

- The MALS detector measures the scattering intensity at multiple angles.

- The software combines these signals with the dn/dc value (refractive index increment) for the protein-detergent complex to calculate the absolute molecular mass across the entire elution peak.

Interpretation: A homogeneous, monodisperse protein sample will produce a single, symmetric peak with a constant molecular mass across the peak. Fluctuations in mass or multiple peaks indicate heterogeneity, aggregation, or different oligomeric states.

Protocol 2: Confirming Oligomerization by 05SAR-PAGE and Western Blot

Objective: To independently verify the oligomeric state of membrane proteins using a gentle electrophoresis method.

Materials:

- Purified membrane protein sample.

- Gel electrophoresis system.

- 05SAR-PAGE gel (containing 0.05% sarkosyl) [40].

- Transfer system for Western blotting.

- Protein-specific primary antibody and labeled secondary antibody.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Mix the protein sample with a non-reducing, non-denaturing loading buffer.

- Electrophoresis: Load the sample and run the 05SAR-PAGE gel at constant voltage under cooling conditions to preserve native complexes [40].

- Western Blot: Transfer the separated proteins from the gel to a membrane.

- Detection: Incubate the membrane with a primary antibody specific to your protein, followed by a labeled secondary antibody. Detect the signal.

Interpretation: The apparent molecular weight of the band(s), compared to a standard ladder, indicates the oligomeric state (e.g., monomer, dimer, trimer). A single band suggests homogeneity, while multiple bands suggest multiple states [40].

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: SEC-MALS Workflow for Membrane Proteins

Diagram 2: SEC-MALS Data Interpretation Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Membrane Protein Oligomeric State Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| LS-Certified SEC Columns | Pre-treated packing material minimizes particle fines, reducing background noise in light scattering detectors [37]. |