Validating Protein Stability Design: From Computational Methods to Cross-Family Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current landscape, methodologies, and validation frameworks for computational protein stability design.

Validating Protein Stability Design: From Computational Methods to Cross-Family Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current landscape, methodologies, and validation frameworks for computational protein stability design. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of stabilizing proteins, examines cutting-edge AI-driven and multimodal design tools, and addresses critical challenges in functional preservation and prediction. By presenting comparative analyses of methods across diverse protein families and outlining robust experimental validation strategies, this review serves as a guide for reliably enhancing protein stability for therapeutic and biotechnological applications, ultimately aiming to bridge the gap between computational prediction and experimental reality.

The Stability Imperative: Why Protein Design is Crucial for Therapeutics and Research

The Impact of Marginal Stability on Heterologous Expression and Drug Development

Proteins exist in a delicate equilibrium, and their functional, folded state is often only marginally more stable than a spectrum of inactive, misfolded, or aggregated states [1]. This marginal stability is a prevalent characteristic among natural proteins, a phenomenon largely explained by evolutionary pressures that select for functional efficiency—which often requires conformational dynamics—over maximal stability [2]. While this trait is advantageous in native physiological contexts, it poses a significant bottleneck in biotechnology and pharmaceutical development, particularly during the heterologous expression of proteins in non-native host systems [1] [2].

The challenges of marginal stability are multifaceted. Marginally stable proteins are prone to low expression yields, misfolding, and aggregation when produced in heterologous hosts like bacteria or yeast, which may lack the specialized chaperone systems of the native organism [1] [3]. This directly impacts the feasibility of producing protein-based therapeutics and research reagents. Furthermore, in drug development, a protein therapeutic's stability influences its shelf-life, in vivo efficacy, and immunogenicity [2]. Consequently, developing robust methods to predict and enhance protein stability is a critical objective in modern protein science. This review examines the impact of marginal stability on heterologous expression and drug development, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of validating stability design methods across diverse protein families. We synthesize recent experimental data and compare advanced computational and experimental strategies aimed at overcoming these stability-related hurdles.

Quantitative Impact of Marginal Stability on Expression and Function

The detrimental effects of marginal stability on heterologous expression and protein function are well-documented. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies that illustrate how stability engineering can reverse these effects.

Table 1: Experimental Data on Stability Engineering Outcomes

| Protein / System | Stability Metric | Expression & Functional Outcomes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria vaccine candidate RH5 | ~15°C increase in thermal denaturation temperature | Shift from expensive insect cell to robust E. coli expression; enhanced resilience for distribution [1]. | [1] |

| Allose binding protein | ∆Tm ≥ 10 °C | 17-fold higher binding affinity; retention of functional conformational changes [4]. | [4] |

| Engineered Aspergillus niger chassis (AnN2) | N/A (Reduced background protein secretion) | Successful secretion of four diverse heterologous proteins with yields of 110.8 to 416.8 mg/L in shake-flasks [5]. | [5] |

| Endo-1,4-β-xylanase & TEM β-lactamase | ∆Tm ≥ 10 °C | Maintained or surpassed wild-type catalytic activity despite dozens of mutations [4]. | [4] |

| OXA β-lactamase | ∆Tm ≥ 10 °C | Altered substrate selectivity, demonstrating controlled functional reprogramming [4]. | [4] |

The data reveals a consistent theme: enhancing stability frequently correlates with improved expression and often enables, rather than compromises, superior function. The ability of designed proteins to not only withstand higher temperatures but also exhibit increased binding affinity or altered specificity underscores the profound link between stability and functional robustness.

Experimental Protocols for Stability Design and Validation

Evolution-Guided Atomistic Design for Stability Optimization

This protocol combines evolutionary information with physical calculations to optimize protein stability while preserving the native fold and function [1].

- Sequence Alignment and Analysis: A multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of homologous proteins is generated. The natural diversity at each amino acid position is analyzed to identify evolutionarily conserved residues.

- Filtering Design Space: Positions critical for function or folding (inferred from evolutionary conservation) are typically fixed. The remaining positions are considered for mutation, but the set of allowed amino acids is restricted to those frequently observed in the MSA. This implements a form of negative design by excluding sequences prone to misfolding or aggregation [1].

- Atomistic Design Calculations: Using software like Rosetta, sequence variants within the filtered design space are generated. These variants are evaluated based on atomistic force fields that calculate the energy of the protein in its desired folded state (positive design). The primary goal is to identify sequences predicted to have lower energy (higher stability) in the target structure.

- Experimental Validation: A small number of top-designed sequences are synthesized and expressed in a heterologous host (e.g., E. coli or yeast). Their stability is biophysically characterized (e.g., by measuring melting temperature, ∆Tm, via circular dichroism or differential scanning fluorimetry), and their functional activity is assessed to ensure preservation.

Multimodal Inverse Folding with ABACUS-T

ABACUS-T is a deep learning-based method that redesigns a protein's sequence from its backbone structure, specifically engineered to maintain function [4].

- Input Preparation: The process begins with the target protein's backbone structure. To preserve function, optional inputs can be included:

- Ligand Structures: Atomic coordinates of substrates or small molecule binders.

- Multiple Backbone Conformations: Structures representing different functional states (e.g., open/closed conformations).

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA): Evolutionary information from homologous proteins.

- Sequence-Space Denoising Diffusion: ABACUS-T uses a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM). It starts from a fully "masked" sequence and iteratively refines the amino acid identities at all positions. Each step is conditioned on the input backbone and other functional constraints, and includes self-conditioning from previous steps [4].

- Sidechain Decoding: Unlike many models, at each denoising step, ABACUS-T also decodes the sidechain conformations, leading to more accurate atomic-level modeling [4].

- Sequence Selection and Testing: Designed sequences are selected and subjected to experimental testing. Notably, ABACUS-T has demonstrated the ability to generate highly stable (∆Tm ≥ 10 °C) and functional proteins by testing only a handful of designs, each containing dozens of simultaneous mutations [4].

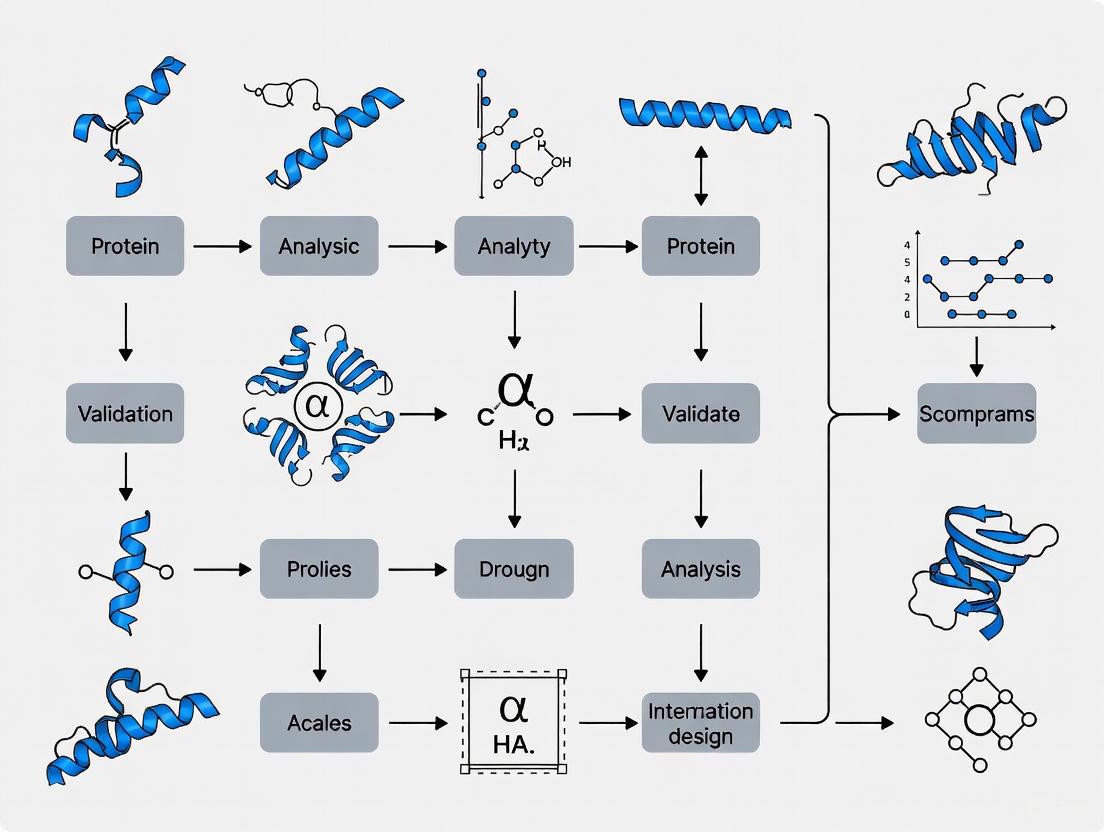

Stability Design Workflow and Host System Engineering

The process of overcoming marginal stability challenges involves both computational protein design and host system engineering. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow between these key strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Success in designing stable proteins and achieving high-yield expression relies on a suite of computational tools, experimental reagents, and host systems.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Stability and Expression Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Design Suites | In silico protein stability optimization and de novo design. | Rosetta: Physics-based modeling and design [1]. ABACUS-T: Multimodal inverse folding that integrates structure, language models, and MSA [4]. RFpeptides: Denoising diffusion-based pipeline for designing macrocyclic binders [6]. |

| Stability Assessment Kits | Experimental measurement of protein thermal stability. | Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF): Uses a fluorescent dye to measure protein unfolding at different temperatures. |

| Heterologous Expression Hosts | Production of recombinant proteins. | S. cerevisiae: Eukaryotic host for proteins requiring disulfide bonds or glycosylation [3]. A. niger: Industrial filamentous fungus with high secretion capacity; chassis strains like AnN2 reduce background protease activity [5]. |

| Gene Integration Systems | Stable, high-copy number integration of target genes. | CRISPR/Cas9-assisted systems: For precise genomic editing and multi-copy integration into high-expression loci [5] [3]. |

| Secretion Pathway Components | Engineering to enhance protein folding and secretion. | COPI/COPII vesicle trafficking genes: Overexpression of components like Cvc2 (COPI) can enhance secretion yield [5]. |

Marginal stability is a fundamental property of natural proteins that presents a formidable challenge in applied biotechnology. As the data and methodologies reviewed here demonstrate, the convergence of evolution-guided principles with advanced AI-driven design is creating a powerful paradigm for overcoming this challenge. The experimental successes of methods like ABACUS-T, which can simultaneously enhance stability and function with remarkable efficiency, validate the premise that stability design rules are becoming broadly applicable across protein families. Furthermore, the synergy between computational protein design and sophisticated host system engineering is paving the way for a new era in drug development. This integrated approach enables the reliable production of previously intractable therapeutic targets, the creation of hyperstable vaccine immunogens, and the design of novel protein and peptide therapeutics with tailored properties. As these tools continue to evolve and be validated across an ever-wider range of proteins, they promise to make computational stability design a mainstream component of protein science and biopharmaceutical development.

The Inverse Folding Problem and its Evolution into the Inverse Function Problem

The inverse folding problem represents a fundamental challenge in computational biology: designing amino acid sequences that fold into a predetermined three-dimensional protein structure. This stands in direct contrast to the protein folding problem, which predicts a structure from a given sequence, a task revolutionized by tools like AlphaFold. In recent years, however, the field has witnessed a significant evolution—what we term the "inverse function problem"—which extends beyond structural compatibility to actively design sequences that fulfill specific functional roles, such as catalytic activity, molecular binding, or therapeutic potency. This paradigm shift moves computational protein design from merely replicating structural blueprints to engineering functional biomolecules with enhanced or entirely novel capabilities.

This transition is particularly critical within protein stability engineering, where the overarching goal is to design variants with improved stability while retaining, or even enhancing, biological function. Traditional directed evolution approaches, while successful, often require extensive experimental screening. The emergence of machine learning-guided inverse folding offers a transformative alternative, enabling more efficient exploration of sequence space while directly incorporating functional constraints into the design process. This guide provides a comparative analysis of leading computational methodologies driving this evolution, examining their experimental validation, and performance across diverse protein families.

Core Methodologies and Comparative Performance

The landscape of inverse folding models is diverse, encompassing various architectural approaches and training strategies. The table below compares several leading models, highlighting their key features, underlying principles, and performance on standard benchmarks.

Table 1: Comparison of Leading Inverse Folding Models and Their Capabilities

| Model Name | Core Methodology | Key Differentiating Features | Reported Sequence Recovery | Functional Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-informed Language Model [7] | Protein language model augmented with backbone coordinates. | Autoregressive; trained on inverse folding objective; generalizes to complexes. | N/A (Demonstrated ~26-fold neutralization improvement in antibodies) | Implicitly learned features of binding and epistasis. |

| ProteinMPNN [8] [9] | SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network. | Fast, robust; allows chain fixing; offers soluble-protein trained version. | ~58% (CATH benchmark, varies by version and training set) [9] | Limited; requires explicit residue fixing for function. |

| ESM-IF1 [9] | Language model trained on sequences and structures. | Uses extensive data augmentation with AlphaFold-predicted structures. | High (SOTA on CATH benchmark) [9] | Limited; primarily focused on structure. |

| ABACUS-T [4] | Sequence-space denoising diffusion model. | Unifies atomic sidechains, ligand interactions, multiple backbone states, and MSA. | High precision (specific metrics not provided) | Explicitly models functional motifs and conformational dynamics. |

| ProRefiner [9] | Global graph attention with entropy-based refinement. | Refines outputs of other models; one-shot generation; uses entropy to filter noisy residues. | Consistently improves recovery of base models (e.g., +~5% over ESM-IF1 on CATH) [9] | Can be applied to partial sequence design for functional optimization. |

A critical metric for evaluating these models is their performance on standardized structural design benchmarks. The following table summarizes key quantitative results from independent evaluations on the CATH and TS50 test sets, providing a direct comparison of their sequence design capabilities.

Table 2: Benchmark Performance of Inverse Folding Models on Standardized Datasets

| Model | Training Data | CATH 4.2 Test Set (Recovery) | TS50 Benchmark (Recovery) | Latest PDB (Recovery) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GVP-GNN [9] | CATH 4.2 | ~40% | N/A | N/A |

| ProteinMPNN [9] | PDB Clusters | ~52% | N/A | N/A |

| ProteinMPNN-C [9] | CATH 4.2 | ~58% | N/A | N/A |

| ESM-IF1 [9] | CATH 4.3 + 12M AF2 Structures | ~65% | N/A | N/A |

| ProRefiner (with ESM-IF1) [9] | CATH 4.2 | ~70% | N/A | N/A |

Experimental Validation and Protocols for Stability and Function

The true test of any inverse folding model lies in experimental validation. The transition to solving the "inverse function problem" requires rigorous assessment of both stability and function. The following experimental protocols are commonly used to validate computational designs.

Key Experimental Protocols

Thermal Shift Assays (TSA): This is a standard method for quantifying protein thermostability.

- Procedure: The protein is mixed with a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) whose fluorescence increases upon binding hydrophobic patches exposed during unfolding. The sample is heated at a controlled rate (e.g., 1°C/min) while fluorescence is monitored. The melting temperature (Tm) is defined as the midpoint of the unfolding transition curve [4] [10].

- Application: Used to measure the increase in Tm (∆Tm) of designed variants compared to wild-type, with improvements of ≥10°C being a common target for successful stabilization [4].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Biolayer Interferometry (BLI): These techniques quantify binding affinity and kinetics for therapeutic antibodies or enzymes.

- Procedure: The target antigen is immobilized on a sensor chip (SPR) or biosensor tip (BLI). Purified protein designs are flowed over the surface at varying concentrations. The association and dissociation phases are monitored in real-time to calculate the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) [7].

- Application: Validates improvements in binding affinity. For instance, a structure-informed model achieved a 37-fold improvement in KD for an antibody against SARS-CoV-2 variants [7].

Enzyme Activity Assays: These are essential for validating the functional integrity of designed enzymes.

- Procedure: The catalytic activity of wild-type and designed enzymes is measured under standardized conditions. For β-lactamases, this involves monitoring the hydrolysis of nitrocefin, a chromogenic substrate, by the increase in absorbance at 486 nm over time [4]. Specific activity (e.g., μmol substrate/min/μmol enzyme) is calculated and compared.

- Application: ABACUS-T redesigned TEM β-lactamase and endo-1,4-β-xylanase variants that maintained or surpassed wild-type activity despite dozens of mutations [4].

Performance in Functional Protein Engineering

The table below synthesizes experimental outcomes from recent studies that exemplify the "inverse function" approach, demonstrating simultaneous enhancement of stability and function.

Table 3: Experimental Validation of Inverse Folding for Functional Protein Enhancement

| Protein Target | Model Used | Stability Outcome | Functional Outcome | Experimental Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 mAbs (Ly-1404, SA58) [7] | Structure-informed Language Model | N/A | Up to 26-fold improvement in viral neutralization; 37-fold improved affinity. | 25-31 variants tested |

| Allose Binding Protein [4] | ABACUS-T | ∆Tm ≥ 10°C | 17-fold higher ligand affinity; retained conformational change. | A few designs tested |

| TEM β-lactamase [4] | ABACUS-T | ∆Tm ≥ 10°C | Maintained or surpassed wild-type catalytic activity. | A few designs tested |

| Endo-1,4-β-xylanase [4] | ABACUS-T | ∆Tm ≥ 10°C | Maintained or surpassed wild-type catalytic activity. | A few designs tested |

| Transposase B [9] | ProRefiner | N/A | 6 of 20 designed variants showed improved gene editing activity. | 20 variants tested |

Successful application of inverse folding requires a suite of computational and experimental tools. The following table details essential "research reagent solutions" for scientists in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Inverse Folding Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example or Note |

|---|---|---|

| Inverse Folding Models | Generates candidate sequences for a target structure. | ProteinMPNN (fast, good for scaffolding), ABACUS-T (for function-aware design). |

| Protein Folding Predictors | Validates that designed sequences fold into the target structure. | AlphaFold2, ESMFold [8] [11]. TM-Score is a key validation metric [11]. |

| Structure Visualization | Visualizes and analyzes 3D protein structures and designs. | PyMOL, UCSF Chimera. |

| Fluorescent Dye | Reports on protein unfolding in thermal shift assays. | SYPRO Orange [4]. |

| Chromogenic Substrate | Measures enzyme activity through a colorimetric change. | Nitrocefin for β-lactamase activity [4]. |

| Biosensor Instrument | Measures binding affinity and kinetics (BLI). | ForteBio Octet systems. |

Visualizing the Evolution from Inverse Folding to Inverse Function

The logical progression from a structure-centric to a function-aware design paradigm involves the integration of multiple data types and feedback loops, as illustrated in the workflow below.

Diagram 1: The evolving inverse folding workflow, integrating structural validation and functional constraints to solve the inverse function problem.

The field of computational protein design is undergoing a decisive shift from the inverse folding problem toward the more ambitious inverse function problem. As evidenced by the comparative data, models like ABACUS-T and advanced refinement strategies like ProRefiner are leading this charge by integrating evolutionary information, ligand interactions, and conformational dynamics directly into the sequence design process. The experimental successes—achieving double-digit increases in thermostability alongside significantly enhanced antibody neutralization, enzyme activity, and altered substrate specificity—demonstrate the profound potential of this approach. For researchers focused on validating stability designs across protein families, the key insight is that multimodal models that unify structural, evolutionary, and functional data are consistently outperforming older, structure-only methods. By leveraging these advanced tools and the accompanying experimental frameworks, scientists can now engineer stable, functional proteins with a efficiency and success rate that was previously unattainable.

The Vast but Constrained Protein Functional Universe Unexplored by Natural Evolution

The protein functional universe encompasses all possible amino acid sequences, their three-dimensional structures, and the biological activities they can perform. This theoretical space includes not only the folds and functions observed in nature but also every other stable protein fold and corresponding activity that could potentially exist [12]. Despite the extraordinary diversity of natural proteins, comparative analyses suggest that known functions represent only a tiny subset of the diversity that nature can produce [12]. The known natural fold space appears to be approaching saturation, with recent functional innovations predominantly arising from domain rearrangements rather than genuinely novel structural elements [12].

The exploration of this universe faces two fundamental challenges: the problem of combinatorial explosion and the constraints of natural evolution. For a mere 100-residue protein, 20^100 (≈1.27 × 10^130) possible amino acid arrangements exist, exceeding the estimated number of atoms in the observable universe (~10^80) by more than fifty orders of magnitude [12]. Meanwhile, natural proteins are products of evolutionary pressures for biological fitness, not optimized as versatile tools for human utility. This "evolutionary myopia" has constrained exploration to functional neighborhoods immediately surrounding natural sequences, leaving vast regions of possible sequence-structure-function space uncharted [12].

The Constraints of Natural Evolution

Evolutionary Barriers to Exploring Novel Protein Space

Natural evolution operates under constraints that fundamentally limit its ability to explore the full protein universe. Proteins must maintain folding stability and biological function throughout evolutionary trajectories, creating fitness barriers that obstruct paths to novel structures [13]. This phenomenon results in a cusped relationship between sequence and structure divergence—sequences can diverge up to 70% without significant structural evolution, but below 30% sequence identity, structural similarity abruptly decreases [13].

This nonlinear relationship emerges from selection for protein folding stability in divergent evolution. Fitness constraints prevent the emergence of unstable evolutionary intermediates, enforcing paths that preserve protein structure despite broad sequence divergence [13]. On longer timescales, evolution is punctuated by rare events where fitness barriers are overcome, enabling discovery of new structures [13]. The strength of selection for folding stability thus modulates a protein's capacity to evolve new structures, with less stable proteins proving more evolvable at the structural level [13].

Documented Evidence of Evolutionary Constraints

The scale of this constraint becomes evident when comparing known protein sequences to theoretical possibilities. While resources like the MGnify Protein Database catalog nearly 2.4 billion non-redundant sequences and the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database contains ~214 million predicted structures, these datasets constitute an infinitesimally small portion of the theoretical protein functional space [12]. Public datasets remain biased by evolutionary history and assay feasibility, channeling data-driven methods toward well-explored regions of sequence-structure space [12].

Table 1: Documented Evolutionary Constraints in Protein Sequence-Structure Space

| Constraint Factor | Impact on Protein Diversity | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Folding Stability Requirements | Limits evolutionary paths to those maintaining stability, creating fitness valleys that block access to novel folds [13] | Computational models show structure evolution traverses unstable intermediates; less stable proteins are more evolvable [13] |

| Functional Conservation Pressure | Maintains essential biological functions, restricting exploration of sequences without immediate fitness benefits [12] | Natural enzyme engineering shows catalytic efficiency optima often exceed natural levels, indicating evolutionary sub-optimization [14] |

| Domain Rearrangement Preference | Favors recombination of existing domains over de novo emergence of structural motifs [12] | Analysis of protein families shows recent innovations predominantly from domain shuffling rather than novel fold discovery [12] |

| Sequence-Structure Divergence Cusp | Creates "twilight zone" below 30% sequence identity where structural prediction from sequence becomes unreliable [13] | Bioinformatics studies of SCOP folds reveal abrupt decrease in structural similarity below 30% sequence identity [13] |

Computational Strategies to Overcome Evolutionary Constraints

Inverse Folding and De Novo Protein Design

To transcend natural evolutionary constraints, researchers have developed computational strategies that actively design proteins rather than modifying natural templates. Inverse folding approaches aim to identify amino acid sequences that fold into a given backbone structure, enabling extensive sequence changes while maintaining structural integrity [4]. However, traditional inverse folding models often produce functionally inactive proteins because they don't impose sequence restraints necessary for functions like substrate recognition or chemical catalysis [4].

The ABACUS-T model represents a multimodal inverse folding approach that unifies several critical features: detailed atomic sidechains and ligand interactions, a pre-trained protein language model, multiple backbone conformational states, and evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignment (MSA) [4]. This integration enables the generation of functionally active sequences without having to explicitly fix predetermined "functionally important" residues [4]. In experimental validations, ABACUS-T redesigned proteins showed notable improvements—an allose binding protein achieved 17-fold higher affinity while retaining conformational change, while redesigned endo-1,4-β-xylanase and TEM β-lactamase maintained or surpassed wild-type activity with substantially increased thermostability (∆Tm ≥ 10 °C) [4].

AI-Driven Exploration of Novel Protein Space

Artificial intelligence has enabled a paradigm shift from optimizing existing proteins to designing entirely novel sequences. AI-driven de novo protein design uses generative models, structure prediction tools, and iterative experimental validation to explore protein sequences beyond natural evolutionary pathways [12]. These approaches leverage statistical patterns from biological datasets to establish high-dimensional mappings between sequence, structure, and function [12].

A particularly powerful framework employs controllable generation, where models are conditioned on desired functions [15]. Researchers can specify target chemical reactions—even those without natural enzyme counterparts—and the model generates novel protein sequences predicted to catalyze them [15]. This transforms discovery from a search process into a design problem. When integrated with automated laboratory systems that enable continuous design-build-test-learn cycles, these approaches create a powerful engine for exploring the uncharted protein universe [16] [15].

Figure: Computational strategies overcome natural evolution constraints through inverse folding and AI-driven generation, validated by automated experimentation.

Experimental Validation of Designed Proteins

Methodologies for Assessing Stability and Function

Validating computationally designed proteins requires rigorous experimental assessment of stability and function. Two primary methods dominate the field: equilibrium unfolding measurements that determine thermodynamic stability, and kinetic stability assessments that measure resistance to irreversible denaturation [14].

Equilibrium unfolding typically uses urea or other chemical denaturants with spectroscopic detection (circular dichroism, intrinsic fluorescence) to monitor the folded-to-unfolded transition. Data are analyzed to calculate the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) for unfolding, with extrapolation to zero denaturant concentration yielding ΔGH₂O [14]. Kinetic stability measurements involve heating protein samples, then cooling and measuring remaining catalytic activity. The ratio of half-lives for mutant versus wild-type proteins yields the difference in Gibbs free energy of activation for activity loss according to: ΔΔG‡ = RT ln(t½,mutant / t½,wildtype) [14].

Table 2: Experimental Validation Methods for Designed Proteins

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Measured Parameters | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Stability | Urea-induced unfolding with CD/fluorescence detection [14] | ΔG (folding free energy), ΔGH₂O (in water) [14] | Measures reversible unfolding; provides fundamental thermodynamic parameters [14] | May not reflect stability under application conditions; requires reversible unfolding [14] |

| Kinetic Stability | Heat inactivation assays, residual activity measurement [14] | t½ (half-life), ΔΔG‡ (activation energy) [14] | Reflects practical stability under application conditions; measures irreversible denaturation [14] | Mechanism complex (unfolding + aggregation); difficult to connect to molecular changes [14] |

| High-Throughput Stability | cDNA display proteolysis [17], yeast display proteolysis [17] | Protease resistance, inferred ΔG values [17] | Enables massive scale (≈900,000 domains/week); good correlation with traditional methods [17] | Model limitations for partially folded states; reliability limits at stability extremes [17] |

| Functional Characterization | Enzyme kinetics, binding affinity measurements, biological activity assays [18] | KM, kcat, IC50, KD [18] | Directly measures protein function; most relevant for applications [18] | Low throughput; requires specific assays for each protein [18] |

Comparative Performance of Engineering Strategies

Different protein engineering strategies yield varying success rates and stabilization levels. A comparative study of five strategies applied to an α/β-hydrolase fold enzyme (salicylic acid binding protein 2, SABP2) revealed distinct performance characteristics [14]. Location-agnostic methods (e.g., random mutagenesis via error-prone PCR) yielded the highest absolute stabilization (average 3.1 ± 1.9 kcal/mol), followed by structure-based approaches (2.0 ± 1.4 kcal/mol) and sequence-based methods (1.2 ± 0.5 kcal/mol) [14].

The mutation-to-consensus approach demonstrated the best balance of success rate, degree of stabilization, and ease of implementation [14]. This strategy hypothesizes that evolution conserves important residues, and positions where the target protein differs from consensus are more likely to be stabilizing when mutated to the consensus residue [14]. Automated programs for predicting consensus substitutions are publicly available to facilitate this approach [14].

Table 3: Comparison of Protein Engineering Strategies

| Engineering Strategy | Key Principles | Stabilization Performance | Success Rate | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location-Agnostic Random Mutagenesis [14] | Random mutations throughout sequence; screening of large variant libraries [14] | 3.1 ± 1.9 kcal/mol average improvement [14] | 67% of reports yielded >2 kcal/mol improvements [14] | High (requires large library construction & screening) [14] |

| Structure-Based Design [14] | Computational modeling of molecular interactions (Rosetta, FoldX) [14] | 2.0 ± 1.4 kcal/mol average improvement [14] | 37% of reports yielded >2 kcal/mol improvements [14] | High (requires structural knowledge & expertise) [14] |

| Mutation-to-Consensus [14] | Replace residues with amino acids conserved in homologs [14] | 1.2 ± 0.5 kcal/mol average improvement [14] | High success rate for identified positions [14] | Low (requires multiple sequence alignment) [14] |

| Inverse Folding (ABACUS-T) [4] | Multimodal model integrating structure, language model, MSA, multiple conformations [4] | ΔTm ≥ 10°C while maintaining or improving function [4] | High (successful with testing of only a few designed sequences) [4] | Medium (requires structural input) [4] |

| Automated Continuous Evolution [16] | Growth-coupled selection in automated laboratory systems [16] | Enabled evolution of proteins from inactive precursors to full function [16] | High for complex functions difficult to design rationally [16] | High (requires specialized automated equipment) [16] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Protein Engineering

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Design Platforms | ABACUS-T [4], Rosetta [12], FoldX [14] | Structure-based sequence design, stability prediction, inverse folding [4] [12] [14] | De novo protein design, stability enhancement, function preservation [4] |

| High-Throughput Stability Assays | cDNA display proteolysis [17], yeast display proteolysis [17] | Massively parallel measurement of folding stability for thousands of variants [17] | Mapping stability landscapes, validating designs, training machine learning models [17] |

| Automated Evolution Systems | OrthoRep continuous evolution [16], iAutoEvoLab [16] | Automated, continuous protein evolution with growth-coupled selection [16] | Evolving complex functions, exploring adaptive landscapes, bypassing design challenges [16] |

| Sequence-Function Mapping | Deep mutational scanning [18], site-saturation mutagenesis [18] | Comprehensive characterization of sequence-performance relationships [18] | Understanding mutational effects, guiding library design, improving computational models [18] |

| Structure Prediction Databases | AlphaFold Database [19], ESM Metagenomic Atlas [12] | Access to predicted structures for millions of proteins [19] | Identifying novel folds, functional annotation, template for design [19] |

The constraints of natural evolution have limited the exploration of the protein functional universe to an infinitesimal fraction of its theoretical expanse. However, integrated computational and experimental approaches are now overcoming these constraints. Multimodal inverse folding models like ABACUS-T enable extensive sequence redesign while maintaining function [4], while AI-driven generative approaches facilitate creation of proteins with novel functions [12] [15]. Automated experimental systems enable continuous evolution and high-throughput validation of designed proteins [16] [17].

These advances are transforming protein engineering from a process of local optimization to one of global exploration. By combining computational design with massive experimental validation, researchers can now systematically illuminate the "dark matter" of the protein universe [19], discovering new folds [19], families [19], and functions [15] that natural evolution has never sampled. This expanded access to protein space promises innovations across biotechnology, medicine, and synthetic biology, enabling the design of bespoke biomolecules with tailored functionalities [12]. As these technologies mature, they will increasingly allow researchers to not just explore but actively create within the vast, untapped potential of the protein functional universe.

Within protein engineering, the pursuit of enhanced stability is a cornerstone for developing effective biotherapeutics and industrial enzymes. Achieving this requires a multi-faceted approach targeting three critical objectives: increased melting temperature (Tm), improved solubility, and enhanced resistance to aggregation. These properties are deeply interconnected; for instance, mutations that improve thermostability can sometimes inadvertently promote aggregation, thereby reducing solubility and overall functional yield [20]. This guide objectively compares the performance of modern stability-design strategies, framing the analysis within a broader research thesis on validating these methods across diverse protein families. The data and protocols summarized herein provide a roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to select and implement the most appropriate design strategies for their specific protein engineering challenges.

Comparative Analysis of Protein Stability-Design Strategies

A comparison of key design strategies reveals distinct performance trade-offs in achieving stability objectives. The following table synthesizes quantitative data and experimental outcomes from recent studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Stability-Design Strategies and Their Outcomes

| Design Strategy | Key Features & Inputs | Reported ΔTm | Impact on Solubility & Aggregation | Key Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multimodal Inverse Folding (ABACUS-T) [4] | Integrates backbone structure, atomic sidechains, ligand interactions, multiple sequence alignment (MSA), and a protein language model. | ΔTm ≥ +10°C (in redesigned allose binding protein, xylanase, β-lactamases) | Maintains or improves functional activity; designed proteins show no major solubility issues. | Activity assays, thermal shift assays, binding affinity measurements (e.g., 17-fold higher affinity for allose binding protein). |

| Consensus Design [14] [21] | Derives sequences from multiple sequence alignments (MSA), assigning the most frequent amino acid at each position. | Variable; often increases stability. | Can produce conformationally homogeneous, soluble proteins (e.g., Conserpin) [21]. | Circular Dichroism (CD) for Tm, NMR for dynamics, equilibrium unfolding experiments for ΔG. |

| Structure-Based Computational Design (e.g., Rosetta, FoldX) [14] [21] | Uses physical energy functions to optimize sequences for a given backbone structure or to predict stabilizing point mutations. | Average stabilization: ~2.0 kcal/mol reported for α/β-hydrolase fold enzymes. | Risk of poor solubility and aggregation if stabilizing mutations expose hydrophobic patches (e.g., LinB116) [20]. | Site-saturation mutagenesis combined with activity screening after thermal challenge. |

| Location-Agnostic Methods (e.g., Error-Prone PCR) [14] | Creates random mutations throughout the gene without prior structural or sequence knowledge. | Highest reported stabilization: Average of ~3.1 kcal/mol. | Success depends on screening; can identify highly stable variants without precise solubility targeting. | High-throughput screening of libraries for residual activity after heat incubation. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Stability Designs

Rigorous experimental validation is required to confirm that designed proteins meet stability objectives. The following protocols are standard in the field.

Protocol for Measuring Thermostability (Tm)

- Objective: Quantify the melting temperature (Tm), the temperature at which 50% of the protein is unfolded.

- Method: Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF, or thermal shift assay) [21].

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein sample with a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) that binds to hydrophobic regions exposed upon unfolding.

- Equipment Setup: Use a real-time PCR instrument or dedicated thermal shift scanner.

- Procedure: Heat the sample from 25°C to 95°C with a gradual ramp (e.g., 1°C per minute) while monitoring fluorescence.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence against temperature. The Tm is determined as the inflection point of the resulting sigmoidal curve.

- Data Interpretation: A higher Tm in a designed variant compared to the wild type indicates improved thermostability. This data can be converted to a kinetic stabilization energy (ΔΔG‡) using half-life ratios [14].

Protocol for Assessing Aggregation and Solubility

- Objective: Evaluate the propensity of a protein to aggregate and its solubility under specific conditions.

- Method 1: Accelerated Aggregation Studies [22]

- Sample Preparation: Incubate protein samples at high concentration and elevated temperatures (e.g., 40°C) for extended periods (days to weeks).

- Analysis: Periodically analyze samples using techniques like:

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): To quantify the amount of soluble monomer versus higher-order aggregates.

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): To monitor the increase in particle size over time.

- Method 2: Analysis of Aggregation-Prone Regions [20] [22]

- In-silico Prediction: Use tools to identify "cryptic aggregation-prone regions" that may become exposed during unfolding.

- Experimental Correlation: Combine with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to identify regions exposed during unfolding that correlate with observed aggregation.

Workflow Diagram for an Integrated AI-MD Stability Design Platform

The following diagram illustrates a modern computational workflow that integrates artificial intelligence and molecular dynamics for predicting and designing protein stability, particularly against aggregation.

AI-MD Workflow for Aggregation Prediction - An integrated platform that starts from sequence, predicts structure, simulates dynamics, calculates novel surface features, and uses machine learning to predict aggregation propensity [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Success in protein stability design relies on a suite of specialized reagents and software tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Stability Design

| Tool/Reagent Name | Category | Primary Function in Stability Design |

|---|---|---|

| SYPRO Orange Dye [21] | Chemical Reagent | Fluorescent dye used in Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) to measure protein thermal unfolding and determine Tm. |

| Rosetta Software Suite [14] [23] [24] | Computational Tool | A comprehensive platform for protein structure prediction, design, and energy-based stability calculations (e.g., ΔΔG). |

| FoldX [14] [24] | Computational Tool | A molecular modeling algorithm for the rapid in-silico evaluation of the effect of mutations on protein stability and interactions. |

| ENDURE Web Application [23] | Computational Tool | Provides an interactive workflow for energetic analysis of protein designs, helping select optimal mutants for experimental testing. |

| RaSP (Rapid Stability Predictor) [24] | Computational Tool | A deep learning-based method for making rapid predictions of changes in protein stability (ΔΔG) upon mutation. |

| Gromacs [22] | Computational Tool | A software package for performing molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, used to study protein dynamics and unfolding pathways. |

The Computational Toolkit: AI, Multimodal Models, and Stability Design Strategies

Protein stability is a fundamental property essential for biological function, yet it presents a major challenge for protein engineers and drug developers. The stability of a protein's native fold is marginal, typically only 5–15 kcal mol⁻¹ more stable than its unfolded state, meaning even single mutations can lead to destabilization and loss of function [25]. For decades, scientists have sought reliable methods to predict and engineer protein stability, with two dominant paradigms emerging: physics-based atomistic simulations that model molecular interactions from first principles, and evolution-guided approaches that extract information from natural sequence variation across protein families. This review objectively compares these methodologies, examining their performance in predicting mutational effects and designing stable proteins, with particular focus on their validation across diverse protein families. Understanding the relative strengths and limitations of these approaches is crucial for researchers aiming to develop more effective therapeutics, enzymes, and biomaterials with enhanced stability properties.

Methodological Foundations: A Tale of Two Approaches

Evolution-Guided Design Principles

Evolution-guided protein design operates on the principle that modern protein sequences contain information about the structural and functional constraints that have shaped their evolution. These methods leverage the evolutionary record encapsulated in multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) to infer which amino acid combinations are likely to fold into stable, functional proteins [26]. The core assumption is that natural selection has already conducted a massive experiment in protein stability optimization over geological timescales, and this information can be mined to guide engineering efforts.

Key implementations of this approach include:

- EvoDesign: This server uses evolutionary profiles from structurally analogous folds or interfaces to guide replica-exchange Monte Carlo simulations. It combines both monomer structural profiles and protein-protein interaction interface profiles with physical energy terms to design stable proteins and optimize binding interactions [27].

- EVcouplings framework: This method employs maximum entropy models parameterized by site-specific (hᵢ) and pairwise (Jᵢⱼ) constraints learned from MSAs. The fitness of a sequence (σ) is defined by its evolutionary Hamiltonian (EVH), calculated as EVH(σ) = -∑hᵢ(σᵢ) - ∑Jᵢⱼ(σᵢ,σⱼ) [28].

- Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR): This "vertical" strategy reconstructs likely ancestral proteins to provide appropriate backgrounds for studying historical mutations that led to functional diversification, effectively avoiding epistatic conflicts that plague horizontal comparisons between modern sequences [26].

Physics-Based Atomistic Simulations

In contrast to data-driven evolutionary methods, physics-based approaches aim to calculate stability from fundamental physical principles, using force fields to model atomic interactions. These methods include:

- Free Energy Perturbation (FEP): A rigorous statistical thermodynamics approach for calculating free energy differences between states. QresFEP-2 represents a recent advancement implementing a hybrid-topology protocol that combines single-topology backbone representation with dual-topology side chains, balancing accuracy with computational efficiency [29].

- Rosetta Design Suite: This widely used platform employs detailed physical energy functions for protein design and stability prediction, with remarkable successes in designing novel stable folds and enzymes [25].

- FoldX and Eris: Specialized tools for predicting ΔΔG changes from mutations using empirical force fields and simplified geometric parameters [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Methodologies in Protein Stability Design

| Method | Core Principle | Key Inputs | Primary Output | Methodology Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EvoDesign | Evolutionary profile guidance | MSA, Structural templates | Designed sequences with enhanced stability/binding | Evolution-guided |

| EVcouplings | Statistical couplings from MSA | MSA of homologous sequences | Sequences with optimized evolutionary Hamiltonian | Evolution-guided |

| QresFEP-2 | Hybrid-topology free energy calculations | Protein structure, Force field | Predicted ΔΔG for mutations | Physics-based atomistic |

| Rosetta | Physical energy function optimization | Protein structure, Rotamer library | Designed stable sequences/structures | Physics-based atomistic |

| Ancestral Reconstruction | Historical mutation analysis | Phylogeny, Modern sequences | Ancestral proteins and mutational effects | Evolution-guided |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Benchmarking Standards and Performance Metrics

Robust validation is essential for assessing protein stability prediction methods. Community-standard benchmarks typically involve:

- Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) Data: Large-scale experimental measurements of mutational effects, such as those obtained for the GRB2-SH3 domain where ΔΔGf values were inferred for nearly all possible mutations (1,056/1,064) using pooled variant synthesis, selection, and sequencing [30].

- Thermal Stability Assays: Melting temperature (Tm) measurements and denaturation midpoint determinations using techniques like circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry.

- Functional Assays: For enzymes like TEM-1 β-lactamase, activity measurements on substrates (e.g., ampicillin hydrolysis) provide functional validation of stability predictions [28].

- High-Throughput Stability Measurements: Methods like AbundancePCA enable quantitative cellular abundance measurements for thousands of variants simultaneously, providing fitness proxies for stability [30].

Performance is typically quantified using:

- Correlation coefficients (Pearson's r or Spearman's ρ) between predicted and experimental stability measurements

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for ΔΔG predictions

- Variance explained (R²) in combinatorial mutant datasets

- Classification accuracy for identifying stabilizing vs. destabilizing mutations

Evolution-Guided Design Workflow

The typical workflow for evolution-guided design, as implemented in EVcouplings, involves several key stages [28]:

- MSA Construction: A multiple sequence alignment of homologous proteins is generated using tools like jackhmmer, with careful attention to alignment depth and quality.

- Model Building: A maximum entropy model is parameterized with site-specific and pairwise terms from the MSA.

- Model Validation: The model is assessed by its ability to recapitulate known structural contacts and mutation effects from deep mutational scans.

- Sequence Generation: Designed sequences are generated using sampling algorithms (Markov Chain Monte Carlo or Gibbs sampling) that optimize evolutionary fitness while satisfying sequence distance constraints.

- Experimental Testing: Designed variants are characterized for stability (thermal denaturation), structure (circular dichroism, X-ray crystallography), and function (activity assays).

Figure 1: Evolution-Guided Protein Design Workflow. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of using evolutionary information to design stable proteins, with validation checkpoints to ensure model quality.

Physics-Based Simulation Protocol

The QresFEP-2 protocol exemplifies modern physics-based approaches to stability prediction [29]:

- System Preparation: The protein structure is prepared with appropriate protonation states and solvation.

- Hybrid Topology Construction: A dual-like hybrid topology combines single-topology representation for backbone atoms with separate topologies for side-chain atoms.

- Restraint Setup: Distance restraints are applied between topologically equivalent atoms to maintain phase-space overlap during alchemical transformations.

- λ-Window Simulations: Multiple independent molecular dynamics simulations are performed at intermediate λ values between wild-type (λ=0) and mutant (λ=1) states.

- Free Energy Integration: The free energy difference is calculated by integrating over the λ pathway using Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) or similar methods.

- Error Analysis: Statistical errors are estimated through bootstrapping or ensemble simulations.

This protocol has been benchmarked on comprehensive protein stability datasets encompassing nearly 600 mutations across 10 protein systems, with additional validation through domain-wide mutagenesis scans.

Performance Comparison Across Protein Families

Quantitative Accuracy Assessment

Recent large-scale studies enable direct comparison of evolution-guided and physics-based methods. A 2024 Nature study on the genetic architecture of protein stability revealed that simple additive energy models based on evolutionary data explain a remarkable proportion of fitness variance in high-dimensional sequence spaces [30]. When trained on single and double mutant data alone, an evolutionary energy model explained approximately 50% of the fitness variance in combinatorial multi-mutants of the GRB2-SH3 domain, most of which contained at least 13 amino acid substitutions.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Protein Systems and Mutation Types

| Method Category | Representative Tool | Accuracy (Correlation with Experiment) | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolution-guided | EVcouplings (TEM-1 β-lactamase) | Spearman ρ = 0.71-0.72 for single mutants [28] | Excellent generalization, handles many mutations | Limited by MSA depth/quality |

| Physics-based | QresFEP-2 (T4 Lysozyme) | Excellent accuracy on comprehensive benchmark [29] | Physical interpretability, no MSA requirement | Computationally intensive, force field inaccuracies |

| Evolution-guided | EvoDesign (Various folds) | Successful design of stable novel binders [27] | Combines evolutionary and physical constraints | Primarily for structure-based design |

| Evolution-guided | Additive Energy Model (GRB2-SH3) | R² = 0.63 for combinatorial mutants [30] | Simple, interpretable, captures global epistasis | Misses specific pairwise interactions |

| Hybrid | Evolution + Solvent Accessibility | Similar accuracy to machine learning methods [31] | Balance of evolutionary and structural information | Implementation complexity |

The addition of pairwise energetic couplings to evolutionary models further improves performance. For the GRB2-SH3 domain, including second-order energetic couplings increased the variance explained from 63% to 72%, demonstrating that while additive effects dominate, specific epistatic contributions are measurable and important for accurate prediction [30]. These couplings were found to be sparse and associated with structural contacts and backbone proximity.

Case Study: TEM-1 β-Lactamase Engineering

A compelling demonstration of evolution-guided design comes from the engineering of TEM-1 β-lactamase using the EVcouplings framework [28]. Researchers generated variants with sequence identities to wild-type TEM-1 ranging from 98% down to 50%, including one design with 84 mutations from the nearest natural homolog. Remarkably, nearly all 14 experimentally characterized designs were functional, with large increases in thermostability and increased activity on multiple substrates, while maintaining nearly identical structure to the wild-type enzyme.

This achievement is particularly significant because previous studies had shown that introducing 10 random mutations to TEM-1 completely abrogates enzyme activity, highlighting the power of evolution-guided methods to enable large jumps in sequence space while maintaining or enhancing function [28].

Case Study: SH3 Domain Stability Landscapes

A massive experiment on the FYN-SH3 domain challenged conventional wisdom about protein stability [32]. Contrary to the prevailing "house of cards" metaphor where any core mutation collapses the structure, researchers found that SH3 retained its shape and function across thousands of different core and surface combinations. By testing hundreds of thousands of variants, they identified that only a few true "load-bearing" amino acids exist in the protein's core, with physical rules governing stability being more like Lego than Jenga.

Machine learning applied to this large dataset produced a tool that could accurately predict SH3 stability, correctly identifying almost all natural SH3 domains as stable even with less than 25% sequence identity to the human version used for training [32]. This demonstrates the generalizability of evolution-guided stability predictions across protein families.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Protein Stability Studies

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| EvoDesign Server | Web Server | Evolution-guided protein design | Freely available online |

| EVcouplings Framework | Software Package | Evolutionary covariance analysis | Open source |

| QresFEP-2 | Software Module | Free energy perturbation calculations | Integrated with Q molecular dynamics |

| Rosetta | Software Suite | Physics-based protein design | Academic and commercial licenses |

| FoldX | Software Plugin | Rapid stability prediction | Freely available for academics |

| AbundancePCA | Experimental Method | High-throughput stability measurement | Protocol described in literature |

| ProTherm Database | Database | Curated protein stability data | Publicly accessible |

Integration Strategies and Future Directions

The most powerful approaches emerging in protein stability design combine evolutionary information with physical principles. For instance, simply combining evolutionary features with a basic structural feature—the relative solvent accessibility of mutated residues—can achieve prediction accuracy similar to supervised machine learning methods [31]. This suggests that hybrid approaches leveraging both the historical information in evolutionary records and the mechanistic understanding from physical models will provide the most robust solutions to protein stability challenges.

Future methodology development will likely focus on:

- Improved epistatic models that better capture the sparse pairwise interactions important for stability

- Machine learning hybrids that integrate evolutionary, physical, and structural features

- High-throughput experimental validation methods that enable rapid testing of computational predictions

- Generalizable force fields that accurately model diverse protein families without requiring extensive evolutionary data

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between evolution-guided and physics-based approaches depends on specific project requirements. Evolution-guided methods typically excel when deep multiple sequence alignments are available and when making large jumps in sequence space, while physics-based approaches provide mechanistic insights and can be applied to novel scaffolds with limited evolutionary information. The most successful engineering campaigns will likely continue to strategically combine both approaches to overcome their respective limitations and leverage their complementary strengths.

Protein engineering aims to overcome the limitations of natural proteins for biotechnological and therapeutic applications. A central challenge in this field is enhancing structural stability without compromising biological function. Traditional computational methods, particularly structure-based inverse folding, have demonstrated remarkable success in designing sequences that fold into stable target structures. However, these hyper-stable designs often suffer from loss of functional activity, as the optimization for folding can neglect residues and conformational dynamics essential for function [4]. This limitation stems from an over-reliance on single structural snapshots and insufficient incorporation of functional constraints during the sequence design process.

The emerging paradigm of multimodal inverse folding addresses this challenge by integrating diverse data types to inform the design process. This approach recognizes that functional proteins exist in conformational ensembles, interact with ligands and other molecules, and contain evolutionary information embedded in their sequences. Here, we examine ABACUS-T (A Backbone based Amino aCid Usage Survey-ligand Targeted), a multimodal inverse folding model that unifies structural, evolutionary, and biochemical information to redesign functional proteins with enhanced stability [4]. Through detailed case studies and comparative analysis, this guide evaluates ABACUS-T's performance against alternative protein design methodologies.

ABACUS-T: Technical Framework and Methodological Innovations

Core Architecture and Design Philosophy

ABACUS-T employs a sequence-space denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) that generates amino acid sequences through successive reverse diffusion steps [4]. Unlike conventional inverse folding models that focus primarily on backbone geometry and sidechain packing, ABACUS-T incorporates multiple critical features into a unified framework:

- Detailed atomic sidechains and ligand interactions: Explicit modeling of molecular interactions preserves functional sites

- Pre-trained protein language model: Leverages evolutionary knowledge from protein sequence databases

- Multiple backbone conformational states: Accounts for functional dynamics beyond single structures

- Evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignment (MSA): Incorporates natural sequence constraints

A key innovation in ABACUS-T is its self-conditioning scheme, where each denoising step is informed by the output amino acid sequence and sidechain atomic structures from the previous step [4]. This iterative refinement process enables more precise sequence selection than single-pass prediction methods.

Experimental Workflow for Protein Redesign

The ABACUS-T methodology follows a systematic workflow for functional protein redesign:

Figure 1: ABACUS-T employs a multimodal workflow that integrates diverse structural and evolutionary data to redesign functional proteins with enhanced stability.

Table 1: Essential Research Resources for Protein Redesign Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Application in Protein Design |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, ESMFold [33] [34] | Validate fold stability of designed sequences |

| Stability Prediction | Pythia, Rosetta, FoldX [35] | Predict ΔΔG changes from mutations |

| Molecular Visualization | PyMOL, ChimeraX | Analyze structural features and binding sites |

| Experimental Validation | Circular Dichroism (CD), Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Enzyme Activity Assays [4] | Measure thermostability (ΔTm), binding affinity, catalytic efficiency |

| Sequence Analysis | HMMER, PSI-BLAST, ClustalOmega [33] | Generate multiple sequence alignments for evolutionary data |

Comparative Performance Analysis: ABACUS-T Versus Alternative Approaches

Experimental Outcomes Across Protein Families

ABACUS-T has been experimentally validated across diverse protein systems, demonstrating its ability to enhance stability while maintaining or improving function. The following table summarizes key performance metrics:

Table 2: Experimental Performance of ABACUS-T Across Protein Families

| Protein System | Key Mutations | Thermostability (ΔTm) | Functional Outcomes | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allose Binding Protein | Dozens of simultaneous mutations [4] | ≥10°C increase [4] | 17-fold higher affinity while retaining conformational change [4] | Retained ligand-induced conformational transition |

| Endo-1,4-β-xylanase | Dozens of simultaneous mutations [4] | ≥10°C increase [4] | Maintained or surpassed wild-type activity [4] | Enzyme activity assays under harsh conditions |

| TEM β-lactamase | Dozens of simultaneous mutations [4] | ≥10°C increase [4] | Maintained or surpassed wild-type activity [4] | Antibiotic resistance profiling |

| OXA β-lactamase | Dozens of simultaneous mutations [4] | ≥10°C increase [4] | Altered substrate selectivity [4] | Specificity profiling against β-lactam antibiotics |

Comparison with Alternative Protein Design Methodologies

Table 3: ABACUS-T Performance Against Alternative Protein Design Approaches

| Design Method | Stability Enhancement | Functional Preservation | Key Limitations | Experimental Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABACUS-T | High (ΔTm ≥10°C) [4] | Excellent (maintained or enhanced activity) [4] | Requires multiple structural/evolutionary inputs | High (multiple successful cases with few designs tested) [4] |

| Traditional Inverse Folding | High [21] | Often compromised [4] | Neglects functional constraints and conformational dynamics | Variable (often requires extensive screening) [4] |

| Consensus Design | Moderate to High [21] | Moderate (depends on MSA quality) | Limited to naturally occurring variations | Moderate [21] |

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction | Moderate to High [21] | Moderate to High [21] | Dependent on accurate phylogenetic reconstruction | Moderate [21] |

| Directed Evolution | Variable (depends on screening method) | High (screening directly for function) | Limited exploration of sequence space (few mutations) | High but resource-intensive [4] |

Advancements Over Previous Inverse Folding Models

ABACUS-T represents a significant advancement over previous inverse folding models through its multimodal approach:

- Functional Preservation: Unlike traditional inverse folding that often produces functionally inactive proteins [4], ABACUS-T maintained or enhanced activity in all tested cases [4]

- Extensive Mutations: Successful designs incorporated dozens of simultaneous mutations, far exceeding the typical scope of directed evolution campaigns [4]

- Efficient Screening: Functional variants were identified with testing of only a few designed sequences, dramatically reducing experimental burden [4]

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Redesign Protocol for Enzyme Systems

For enzyme redesign, ABACUS-T follows a structured protocol:

Input Preparation:

- Obtain high-resolution structure with bound ligands or substrates

- Curate multiple sequence alignment from homologous families

- Identify multiple conformational states when available

Sequence Generation:

- Apply denoising diffusion process conditioned on structural and evolutionary inputs

- Generate multiple sequence variants with dozens of mutations

Experimental Validation:

- Express and purify designed variants

- Assess thermostability via circular dichroism (measuring Tm)

- Evaluate catalytic activity with enzyme-specific assays

- Determine ligand binding affinity where applicable

Key Methodological Innovations in ABACUS-T

ABACUS-T's performance advantages stem from several methodological innovations:

Figure 2: ABACUS-T's core methodological innovations integrate multiple data types and preservation mechanisms to maintain protein function while enhancing stability.

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The development of ABACUS-T represents significant progress in addressing the fundamental challenge of functional protein redesign. By unifying structural, evolutionary, and biochemical information in a single framework, ABACUS-T demonstrates that substantial stability enhancements (ΔTm ≥10°C) can be achieved without compromising biological activity [4]. This multimodal approach effectively bridges the gap between structure-based design and function preservation.

The implications for protein engineering and drug development are substantial. The ability to redesign proteins with enhanced stability while maintaining function opens new possibilities for:

- Engineering robust industrial enzymes for biotechnology

- Developing stable therapeutic proteins with extended shelf-life

- Creating specialized biosensors with tailored properties

- Designing novel biocatalysts with altered substrate specificity

Future developments in multimodal inverse folding will likely focus on incorporating dynamics more explicitly, expanding to membrane protein systems, and improving accuracy for de novo protein design. As the field progresses, the integration of advanced deep learning approaches with biophysical principles promises to further accelerate the design of functional proteins with tailored properties.

The validation of protein stability design methods across diverse protein families is a core challenge in computational biology. Two revolutionary AI approaches—Denoising Diffusion Models and Protein Language Models (exemplified by the ESM family)—offer distinct and complementary pathways for this task. Diffusion models excel in generating novel, thermodynamically stable protein structures by learning the physical principles of folding, while ESM-style PLMs leverage evolutionary information from massive sequence databases to infer protein function and stability from sequence alone. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, experimental protocols, and practical applications to inform researchers' choices in protein engineering campaigns.

Comparative Analysis at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core architectural and performance characteristics of Denoising Diffusion Models and ESM-based Protein Language Models.

Table 1: High-Level Comparison of Denoising Diffusion Models and ESM-based PLMs

| Feature | Denoising Diffusion Models | ESM-based Protein Language Models |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Input | 3D atomic coordinates (Structure) | Amino acid sequences (Sequence) |

| Core Methodology | Iterative denoising of random noise conditioned on constraints [36] [37] | Self-supervised learning on evolutionary-scale sequence datasets [38] [39] |

| Key Output | Novel protein backbone structures and scaffolds [36] [40] | Sequence embeddings, function predictions, variant effects [38] [41] |

| Typical Scope | De novo protein design, motif scaffolding [36] | Transfer learning, fine-tuning for specific prediction tasks [38] [42] |

| Computational Load | High (3D structure generation is resource-intensive) [40] | Variable (Medium-sized models offer efficient transfer learning) [38] |

| Experimental Validation Metric | scRMSD, pLDDT, TM-score [36] | Perplexity, Recovery Rate, Variant effect prediction accuracy [38] [43] |

Performance and Experimental Validation

Performance on Protein Design Tasks

The following table compares the quantitative performance of leading models from both paradigms against key protein design and stability metrics.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Key Protein Design Tasks

| Model / Task | Sequence Recovery (%) | Designability (scRMSD < 2Å) | Success in Low-Data Regimes (Variant Prediction) | Novel Protein Generation (Length) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SALAD (Diffusion) | Information Missing | Matching/Improving state-of-the-art for lengths up to 1,000 residues [36] | Not Directly Applicable | Up to 1,000 residues [36] |

| MapDiff (Diffusion for IPF) | Substantially outperforms state-of-the-art baselines on CATH benchmarks [43] | High-quality refolded structures (via AlphaFold2) closely match native templates [43] | Not Directly Applicable | Not Primary Focus |

| ESM-2 (PLM) | Not Primary Focus | Not Primary Focus | Competitive, but medium-sized models (e.g., 650M) perform well with limited data [38] | Not Primary Focus |

| METL (Biophysics PLM) | Not Primary Focus | Not Primary Focus | Excels; designs functional GFP variants trained on only 64 examples [42] | Not Primary Focus |

Key Experimental Protocols

To ensure the validity and reproducibility of stability design methods, researchers employ several standardized experimental workflows.

1. In-silico Validation of Designed Structures: This is the standard protocol for validating structures generated by diffusion models.

- Methodology: A generated protein backbone is first fed into a sequence design tool (e.g., ProteinMPNN) to propose a amino acid sequence. This sequence is then processed by a structure predictor (e.g., AlphaFold2 or ESMFold) to obtain a predicted 3D structure [36].

- Success Criteria: A design is deemed successful if the predicted structure has high confidence (pLDDT > 70-80) and closely matches the original design, typically with a self-consistent RMSD (scRMSD) of less than 2 Å [36]. The Template Modeling (TM) score is used to assess structural diversity and novelty compared to natural proteins [36].

2. Transfer Learning for Sequence-Function Prediction: This protocol is standard for applying ESM-style PLMs to predict stability and function from sequence data.

- Methodology:

- Embedding Extraction: Pre-trained ESM model processes protein sequences to generate vector representations (embeddings). For global protein properties, mean pooling of residue-level embeddings has been shown to consistently outperform other compression methods [38].

- Model Training: The compressed embeddings are used as input features to train a simple supervised model (e.g., LassoCV regression) to predict experimental measurements, such as thermostability or activity [38].

- Evaluation: Model performance is evaluated by measuring the variance explained ((R^2)) on a held-out test set [38]. This tests the model's ability to generalize from limited experimental data.

The application of these advanced AI models relies on a ecosystem of computational tools and databases.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for AI-Driven Protein Design

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion | Denoising Diffusion Model | Generates novel protein backbone structures; excels at motif scaffolding and conditioning on target structures [40]. |

| SALAD | Sparse Denoising Model | Efficiently generates large protein structures (up to 1,000 residues) and can be combined with "structure editing" for new tasks [36]. |

| ESM-2 & ESM-3 | Protein Language Model | Provides state-of-the-art sequence representations for transfer learning on tasks like function prediction and variant effect analysis [38]. |

| METL | Biophysics-based PLM | A PLM pre-trained on molecular simulation data, excelling at predicting stability and function from very small experimental datasets [42]. |

| ProteinMPNN | Sequence Design Algorithm | The standard tool for fixing the sequence onto a given protein backbone, a critical step after backbone generation [36]. |

| AlphaFold2 | Structure Prediction | The benchmark tool for in-silico validation of designed protein structures and for assessing foldability [36] [43]. |

| CATH Database | Protein Structure Database | Provides topology-based splits for benchmarking inverse folding and design methods, ensuring rigorous evaluation [43]. |

| EnVhogDB | Protein Family Database | An extended database of viral protein families, useful for annotating and understanding the context of designed proteins [44]. |

Within the critical context of validating protein stability across families, Denoising Diffusion Models and ESM-based PLMs are not competing technologies but rather two halves of a complete solution. Diffusion models are the premier choice for de novo design projects where the target is a novel stable fold or a precise structural scaffold, as demonstrated by SALAD's ability to handle large proteins [36]. In contrast, ESM-style PLMs are invaluable for high-throughput analysis and engineering of existing protein families, especially when experimental data is scarce, a task where biophysics-enhanced models like METL excel [42].

The most powerful future workflows will likely integrate both: using diffusion models to invent novel, stable backbones and leveraging the evolutionary wisdom embedded in PLMs to design functional, stable sequences for them. This synergistic approach will significantly accelerate the reliable design of stable proteins for therapeutic and industrial applications.

Proteins are inherently dynamic molecules that exist as ensembles of interconverting conformations, a fundamental property that single-state structural models cannot fully capture [45]. This conformational diversity is crucial for function, enabling mechanisms like allosteric regulation and ligand binding [45]. Traditional protein design approaches often optimize sequences for a single, rigid backbone structure, which can yield hyper-stable proteins that lack functional activity, particularly in enzymes where conformational flexibility is essential for catalysis [4]. The emerging paradigm in computational protein design acknowledges that representing and designing for multiple backbone conformational states is essential for creating proteins that are both stable and functional [4].

This comparison guide evaluates computational methods that address the critical challenge of designing protein sequences that accommodate conformational flexibility and maintain ligand interactions. We objectively analyze tools ranging from molecular mechanics force fields to advanced machine learning platforms, comparing their performance across key metrics including structural accuracy, functional preservation, and stability enhancement. By validating these methods against experimental data across diverse protein families, we provide researchers with evidence-based guidance for selecting appropriate tools for dynamic protein design.

Methodologies for Modeling Multiple Conformational States