Protein Quality Control: The Master Modulator of Bacterial Evolution and a New Frontier in Drug Development

This article synthesizes contemporary research on the bacterial Protein Quality Control (PQC) network, a system of chaperones, proteases, and translational machinery that maintains proteome homeostasis.

Protein Quality Control: The Master Modulator of Bacterial Evolution and a New Frontier in Drug Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes contemporary research on the bacterial Protein Quality Control (PQC) network, a system of chaperones, proteases, and translational machinery that maintains proteome homeostasis. For researchers and drug development professionals, we explore how the PQC network fundamentally shapes molecular evolution by influencing mutational robustness, evolvability, and epistasis. The review further examines cutting-edge methodologies for studying PQC, its role in stress adaptation and antibiotic resistance, and its validation as a therapeutic target for combating bacterial pathogenesis and treating human conformational diseases.

The Proteostasis Machinery: Core Components and Evolutionary Principles

The bacterial protein quality control (PQC) network constitutes an essential cellular system dedicated to maintaining proteome homeostasis (proteostasis)—the state in which proteins are properly folded, regulated, and functional within cells [1]. This sophisticated network comprises specialized genes that facilitate proteostasis through coordinated actions of chaperones, proteases, and protein translational machinery [2] [3]. Beyond its fundamental role in cellular housekeeping, the PQC network participates in vital cellular processes and exerts profound influence on organismal development and evolutionary trajectories [2] [1]. By ensuring proteome stability, the PQC network shapes the relationship between genotype and phenotype, modulating key evolutionary concepts including epistasis, evolvability, and the navigability of protein space [3].

The PQC machinery addresses numerous cellular challenges that threaten protein folding, including temperature-related stress, intracellular crowding (with protein concentrations reaching 200-300 mg/mL), slow translation rates (approximately 4-20 amino acids per second), ribosome exit tunnel sequestration, and incorrect disulfide bridge formation [1]. This review provides a comprehensive technical examination of the bacterial PQC network's components, functions, and experimental methodologies, framed within the context of its significance for evolutionary research and therapeutic development.

Core Components of the Bacterial PQC Network

Molecular Definitions and Functional Relationships

Table 1: Key Definitions in Bacterial PQC Research

| Term | Definition | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Proteostasis | The homeostasis of the proteome, maintained by components that ensure correct protein folding, function, concentration, and cellular localization [1]. | Provides the functional proteome necessary for cellular processes and viability. |

| Protein Quality Control (PQC) | The network of components (chaperones, proteases) that maintain proper protein folding and function, and degrade damaged or unneeded proteins [1]. | Active system that executes proteostasis through folding assistance and degradation. |

| Mutational Robustness | The invariance or resistance of the phenotype to change despite the presence of mutations [1]. | Buffers against deleterious effects of genetic variation, increasing evolutionary stability. |

| Evolvability | The capacity of genotypes to adapt to new environments through mutations, genetic variation, or recombination [1]. | Enhances potential for evolutionary adaptation to changing conditions. |

| Epistasis | Non-additive interactions between mutations that collectively craft phenotypes in unexpected ways based on individual mutation effects [1]. | Influences evolutionary trajectories and adaptive landscape navigation. |

Chaperone Systems: Mechanisms and Evolutionary Impact

The bacterial PQC network features several specialized chaperone systems with distinct but complementary functions. ATP-dependent chaperones utilize energy from ATP hydrolysis to mechanically remodel misfolded or partially unfolded proteins, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis [1].

Chaperonins (Hsp60 proteins) represent a specialized class of ATP-dependent chaperones that assemble into nanocage-like structures. These structures bind and encapsulate misfolded client proteins, creating a controlled environment for folding shielded from interactions with other misfolded proteins that could cause aggregation [1]. In Escherichia coli, the GroEL/GroES system (Hsp60/Hsp10) facilitates folding through one or more cycles of ATP hydrolysis, promoting conformational changes in client proteins [1]. The interior folding cavity of chaperonins generally supports proteins up to 60 kilodaltons, constraining which constituents of the proteome can evolve chaperonin dependence [1].

GroEL interacts with over 250 client proteins from the E. coli proteome, which can be received directly or from other chaperones like the trigger factor (TF) or the Hsp70 system (DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE) [1]. The Hsp70 system performs diverse physiological roles on unfolded peptide segments, while TF operates cotranslationally with the ribosome, functioning as a holdase that stabilizes proteins in their unfolded state during synthesis [1]. TF interacts with the ribosome exit tunnel, binding emerging polypeptides to prevent aggregation with neighboring peptides due to unpaired hydrophobic regions and disordered segments in the nascent chain [1].

Table 2: Major Chaperone Systems in Bacterial PQC

| Chaperone System | Components | Primary Function | Evolutionary Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chaperonins (Hsp60) | GroEL, GroES (in E. coli) | ATP-dependent encapsulation of misfolded proteins (<60 kDa) in folding cage [1]. | Enables folding of essential proteins; promotes mutational robustness and evolvability [1]. |

| Hsp70 System | DnaK, DnaJ, GrpE | ATP-dependent binding to unfolded peptide segments; early folding assistance [1]. | Increases protein stability and adaptability to ecological conditions [1]. |

| Trigger Factor (TF) | Single protein | Ribosome-associated holdase; cotranslational stabilization of nascent chains [1]. | Prevents aggregation during synthesis; maintains folding efficiency under translation stress [1]. |

| ATP-Independent Holdases | Various small HSPs | Prevent aggregation under stress conditions without ATP consumption. | Provides energy-efficient stress response; enables survival in fluctuating environments. |

Proteolytic Systems in Protein Quality Control

The proteolytic arm of the PQC network ensures the removal of irreversibly damaged, misfolded, or unneeded proteins, completing the quality control cycle. While the search results do not provide extensive details on specific bacterial proteases, these systems typically work in concert with chaperones to identify and degrade PQC clients that cannot be properly refolded, preventing toxic aggregate formation and maintaining cellular homeostasis.

Evolutionary Consequences of the PQC Network

Modulating Molecular Evolution

The PQC network serves as a master modulator of molecular evolution in bacteria through several interconnected mechanisms. By buffering the effects of mutations that would otherwise cause protein misfolding, chaperones promote mutational robustness—the invariance of phenotype in the face of genetic variation [1]. This buffering capacity maintains functionality while allowing genetic diversity to accumulate in populations, ultimately enhancing evolvability (the genotypic ability to adapt to new environments) [1].

The GroEL/GroES system exemplifies this evolutionary role, as a subset of GroEL client proteins have evolved complete dependence on chaperonins for proper folding [1]. These chaperone-dependent proteins are often essential to cellular function, directly linking PQC activity to organismal fitness and evolutionary trajectory. Furthermore, by influencing which protein variants remain functional, the PQC network shapes epistatic interactions between mutations and affects the navigability of protein sequence space [2].

PQC in Host-Pathogen Interactions and Antibiotic Resistance

The PQC network plays significant roles in host-parasite interactions, pathogenicity, and antibiotic resistance mechanisms [1]. Bacterial pathogens likely manipulate PQC components to adapt to host environments and withstand immune responses. Additionally, by promoting protein stability under stress conditions, PQC systems may contribute to the evolution and maintenance of antibiotic resistance mechanisms, representing a promising area for therapeutic intervention.

Experimental Approaches for PQC Network Analysis

Protein-Protein Interaction Network Mapping

Comprehensive analysis of the bacterial PQC network requires systematic mapping of protein-protein interactions. The BioPlex methodology represents a powerful approach for large-scale interaction mapping, using high-throughput affinity-purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) to identify interacting partners [4]. This network-based framework readily subdivides into communities corresponding to complexes or clusters of functionally related proteins, revealing functional associations and subcellular localization patterns [4].

Protocol: BioPlex Network Construction for PQC Analysis

- Sample Preparation: Generate bait proteins (2,594 in original BioPlex) tagged with affinity epitope in appropriate bacterial expression system [4].

- Affinity Purification: Perform immunoaffinity purification under native conditions to preserve protein complexes [4].

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Digest purified complexes and analyze by high-resolution LC-MS/MS for peptide identification [4].

- Data Processing: Apply statistical frameworks to identify specific interactions from background contaminants, typically resulting in 23,744 interactions among 7,668 proteins in human systems [4].

- Network Analysis: Subdivide resulting network into communities representing functional complexes; analyze network architecture for biological process enrichment and molecular function associations [4].

Computational Analysis Using stringApp and Cytoscape

The stringApp provides essential computational tools for analyzing and visualizing PQC networks within the Cytoscape environment, bridging the gap between the comprehensive STRING database and flexible network analysis capabilities [5].

Protocol: stringApp Analysis of PQC Components

- Network Retrieval: Import STRING networks into Cytoscape using stringApp, starting from either:

- A list of PQC proteins (chaperones, proteases)

- A PubMed query for PQC-related terms

- Disease associations from DISEASES database [5]

- Network Expansion: Add additional nodes based on connectivity to current selection using the algorithm:

Si = ∑j∈X sij / (∑k sik)αwhere sij represents confidence score between nodes, and α (default 0.5) controls selectivity [5]. - Functional Enrichment Analysis: Retrieve enrichment results for entire network or selected subsets; filter results to show relevant term categories and eliminate redundant terms using Jaccard similarity cutoff [5].

- Data Integration: Augment network with additional data from:

- Small molecule interactions from STITCH

- Subcellular localization from COMPARTMENTS

- Tissue expression from TISSUES

- Drug target information from Pharos [5]

- Cluster Analysis: Apply clusterMaker2 app to identify functional modules within PQC network using appropriate clustering algorithms [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for PQC Investigations

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bacterial PQC Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chaperone/Protease Plasmids | GroEL/GroES, DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE, ClpP overexpression vectors | Functional complementation studies; client protein identification [1]. |

| Affinity Purification Tags | His-tag, FLAG-tag, Streptag | Isolation of protein complexes for AP-MS experiments [4]. |

| STRING Database | stringApp for Cytoscape | Protein-protein interaction network retrieval and analysis [5]. |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | High-resolution LC-MS/MS systems | Identification and quantification of protein interactions and complexes [4]. |

| Cytoscape with Apps | stringApp, clusterMaker2, PTMOracle | Network visualization, clustering, and post-translational modification analysis [5]. |

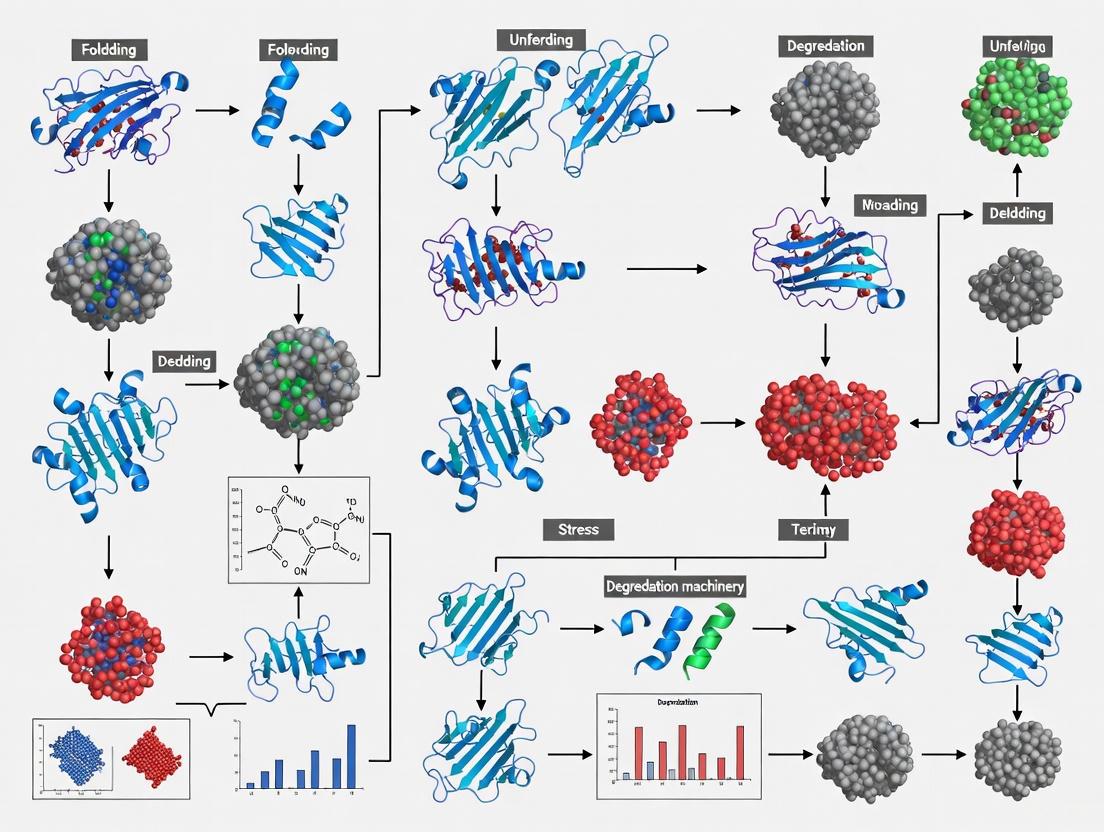

Visualization of the Bacterial PQC Network

The following diagrams illustrate the core architecture and functional relationships within the bacterial protein quality control network, created using Graphviz DOT language with the specified color palette.

Bacterial PQC Network Overview

This diagram illustrates the integrated architecture of the bacterial protein quality control system, showing how chaperone and protease systems coordinate to maintain proteostasis and influence evolutionary outcomes.

PQC Network Analysis Workflow

This workflow diagram outlines integrated experimental and computational approaches for characterizing the bacterial PQC network, from initial methodological approaches through data integration to analytical outcomes.

The bacterial protein quality control network represents a master modulator of molecular evolution, integrating chaperone systems, proteolytic machinery, and translational components to maintain proteostasis while simultaneously shaping evolutionary trajectories. Through its roles in mutational buffering, management of epistatic interactions, and enhancement of evolutionary navigability, the PQC network fundamentally influences the relationship between genotype and phenotype. The experimental frameworks and analytical tools detailed in this review provide researchers with comprehensive methodologies for investigating this sophisticated system, with significant implications for understanding bacterial evolution, host-pathogen interactions, and developing novel antimicrobial strategies that target proteostasis mechanisms.

The maintenance of proteome integrity, or proteostasis, is a fundamental challenge in cellular biology, and bacteria have evolved sophisticated nanomachines to address it. ATP-dependent chaperones form the core of the protein quality control (PQC) network, preventing aggregation, assisting folding, and ensuring proper protein function. The GroEL/GroES (Hsp60/Hsp10) and DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE (Hsp70/Hsp40) systems represent two essential chaperone families that have been evolutionarily conserved across bacterial lineages. These molecular machines employ ATP hydrolysis to power conformational changes that enable them to bind, encapsulate, and release client proteins, thereby facilitating correct folding pathways [6] [7]. Understanding their mechanisms provides not only fundamental insights into bacterial protein folding but also potential avenues for therapeutic intervention, as these systems are crucial for bacterial stress adaptation and virulence.

The GroEL/GroES Chaperonin System

The GroEL/GroES complex, classified as a chaperonin (Hsp60/Hsp10 in eukaryotes), assembles into a large double-ring structure with a central cavity that provides an isolated folding chamber. Each GroEL ring consists of seven identical subunits arranged radially, forming a barrel-like architecture with a molecular weight of approximately ~800 kDa for the core GroEL14-mer [8] [7]. The system operates through a coordinated ATP-driven cycle:

- Substrate Binding: Non-native proteins bind to hydrophobic patches lining the apical domain of the GroEL ring.

- Encapsulation: ATP and GroES binding trigger dramatic conformational changes that enclose the substrate within an encapsulated cage, displacing the hydrophobic binding surfaces and promoting substrate folding in a protected environment.

- Folding and Release: ATP hydrolysis in the cis-ring and subsequent ATP binding to the opposite trans-ring triggers GroES release and substrate ejection [8] [7].

This mechanism allows GroEL/GroES to assist in the folding of approximately 10-15% of cellular proteins in E. coli, typically those in the 20-60 kDa size range that possess complex folding kinetics [8].

The DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE (Hsp70/Hsp40) System

The DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE system represents a more versatile, ATP-dependent chaperone system that functions through transient binding and release cycles rather than encapsulation. The core components include:

- DnaK (Hsp70): The central chaperone that binds hydrophobic patches of substrate proteins. It consists of a nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and a substrate-binding domain (SBD).

- DnaJ (Hsp40): A co-chaperone that stimulates DnaK's ATPase activity and can also bind non-native substrates, presenting them to DnaK.

- GrpE: A nucleotide exchange factor (NEF) that catalyzes ADP release from DnaK, enabling ATP rebinding and substrate release [6] [7].

The functional cycle begins with DnaJ binding to a non-native substrate and recruiting ATP-bound DnaK. DnaJ interaction triggers ATP hydrolysis by DnaK, stabilizing the high-affinity ADP state that tightly binds the substrate. GrpE then catalyzes ADP release, allowing ATP rebinding and substrate release. If the substrate is not properly folded, it can be recaptured for additional folding cycles [6] [7].

Quantitative Analysis of Chaperone Systems

Table 1: Comparative Features of Bacterial ATP-Dependent Folding Nanomachines

| Feature | GroEL/GroES System | DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE System |

|---|---|---|

| Classification | Chaperonin (Hsp60/Hsp10) | Hsp70/Hsp40 System |

| Structure | Double-ring 14mer (GroEL) + Single-ring 7mer (GroES) | Monomeric DnaK + Accessory Proteins |

| Molecular Weight | ~800 kDa (GroEL14) + ~70 kDa (GroES7) | ~70 kDa (DnaK) + ~40 kDa (DnaJ) + ~22 kDa (GrpE) |

| ATP Dependency | Yes (GroEL rings alternate hydrolysis) | Yes (DnaK ATPase cycle) |

| Folding Mechanism | Encapsulation in Anfinsen cage | Transient binding-release cycles |

| Key Co-factors | GroES (lid) | DnaJ (ATPase stimulator), GrpE (NEF) |

| Estimated Substrate Percentage | 10-15% of cellular proteins [8] | Broad, early-acting intervention |

Table 2: Functional Roles in Bacterial Protein Quality Control Network

| Functional Role | GroEL/GroES Contribution | DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| De Novo Folding | Essential for complex proteins >20kDa | Early interaction with nascent chains |

| Stress Protection | Upregulated during heat shock | First responder to proteotoxic stress |

| Cell Cycle Regulation | Cell division (FtsZ, FtsA folding) [6] | DNA replication initiation (DnaA stability) [6] |

| Adaptation | Specialized chaperonins in some bacteria [8] | Regulation of σ32 heat shock factor [6] |

Experimental Methodologies and Research Toolkit

Key Experimental Protocols

Research into these nanomachines employs sophisticated biochemical and biophysical approaches:

Single-Molecule Analysis: Advanced techniques including single-molecule FRET and force spectroscopy have revealed structural heterogeneity of chaperones, folding intermediates, and binding affinities for unfolded chains [7]. These methods allow observation of real-time conformational changes during chaperone cycles.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: All-atom MD simulations spanning microsecond timescales elucidate functional dynamics and allosteric regulation. For chaperone complexes, simulations have analyzed nucleotide-induced conformational changes, client protein interactions, and energy landscapes of folding pathways [9].

Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): This transformative technique has resolved structures of chaperone-client complexes, such as the GR:Hsp90:Hsp70:Hop loading complex and the GR:Hsp90:p23 maturation complex, providing atomic-level insights into client interactions and remodeling mechanisms [9].

Proteomic Approaches for Substrate Identification: Mass spectrometry-based methods have identified numerous substrates for ATP-dependent proteases and chaperones, revealing sequence motifs responsible for recognition and the impact of adaptor proteins on substrate choice [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying ATP-Dependent Folding Nanomachines

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs (AMP-PNP) | Traps chaperones in specific conformational states | Structural studies of GroEL-ATP state [8] |

| Model Substrate Proteins (e.g., GFP, rhodanese) | Well-characterized folding reporters | In vitro refolding assays to quantify chaperone activity |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Probe functional residues in chaperone cycles | Analysis of DnaJ glutamine-12 in protein-protein interactions [11] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Gene editing in bacterial models (e.g., B. subtilis) | Generation of chaperone-deficient strains [11] |

| Protease-Deficient Strains (e.g., WB800N) | Host for recombinant chaperone expression | Improves yield of chaperone proteins [11] |

| σ32 Mutants | Dissect heat shock response regulation | Study DnaKJ/E role in σ32 sequestration [6] |

Integration in Bacterial Protein Quality Control Networks

In bacterial cells, these chaperone systems do not operate in isolation but form an integrated PQC network. In Caulobacter crescentus, for example, both GroEL/GroES and DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE perform essential tasks during normal cell cycle progression and during stress adaptation [6]. DnaKJE is crucial for DNA replication initiation through its regulation of DnaA stability, while GroESL facilitates cell division through its interaction with FtsZ-associated proteins [6]. During proteotoxic stress, DnaK is titrated away from its regulatory target σ32, leading to heat shock protein induction, while both chaperone systems are upregulated to manage increased protein damage [6].

The functional integration extends to interactions with ATP-dependent proteases like ClpXP and ClpAP, which degrade irreparably damaged proteins [10] [6]. This creates a complete proteostasis pipeline where DnaK/J/GrpE and GroEL/GroES attempt refolding, while AAA+ proteases dispose of proteins that cannot be rescued. This network architecture has evolutionary significance, as bacteria frequently exposed to environmental stresses often contain multiple chaperonin genes with specialized functions, increasing the general chaperoning ability or acquiring novel cellular roles [8].

Visualization of Chaperone Mechanisms and Experimental Workflows

GroEL/GroES Functional Cycle

DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE Chaperone Cycle

Experimental Workflow for Chaperone Mechanism Study

The GroEL/GroES and DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE systems represent paradigm-shifting examples of cellular nanomachines that convert chemical energy from ATP hydrolysis into mechanical work for protein folding. Their study continues to reveal fundamental principles of allosteric regulation, cooperative mechanics, and cellular proteostasis management. From an evolutionary perspective, the conservation of these systems across bacterial species underscores their fundamental role in fitness and adaptation. Future research directions include elucidating the complete substrate specificity codes for each system, understanding how chaperone networks are remodeled during stress adaptation, and exploiting these systems as targets for novel antibacterial strategies that disrupt bacterial proteostasis. The integration of structural biology, single-molecule biophysics, and systems biology approaches will continue to decode the sophisticated operation of these essential nanomachines.

In the cellular environment, proteins are perpetually at risk of misfolding due to intrinsic factors such as translational errors and mutations, as well as extrinsic stresses including temperature fluctuations and oxidative stress [12]. The hydrophobic regions of a polypeptide, normally buried within the native structure, become exposed upon misfolding, leading to dysfunctional proteins that can form toxic aggregates and impede essential cellular processes [12]. To combat this threat, cells have evolved a sophisticated protein quality control (PQC) network, a system that is not only vital for cellular survival but also serves as a master modulator of molecular evolution in bacteria [2] [3].

The bacterial PQC network, comprising chaperones, proteases, and the protein translational machinery, maintains proteome homeostasis (proteostasis) by overseeing three fundamental strategies for managing misfolded proteins: refolding them into active conformations, degrading them when they are beyond repair, and sequestering them to limit their proteotoxicity [2] [12]. This tripartite system ensures that the damage is minimized, cellular functionality is preserved, and the detrimental inheritance of damaged proteins across cell generations is limited. Understanding these mechanisms provides a framework for appreciating how proteostasis influences evolutionary processes, including evolvability and the navigation of protein space [2].

The Refolding Machinery: Chaperones and Experimental Restoration

The first line of defense against protein misfolding is the refolding of non-native proteins into their active, native conformations. This process is primarily facilitated by molecular chaperones, which recognize and bind to exposed hydrophobic patches on misfolded proteins, preventing aberrant interactions and providing a conducive environment for correct folding [12].

Key Chaperones in Refolding

- Hsp70 (DnaK in bacteria): Assisted by Hsp40 (DnaJ) co-chaperones, Hsp70 binds to short hydrophobic peptide segments of unfolded proteins. The ATP-dependent cycling of Hsp70 between open and closed conformations facilitates the stepwise folding of client proteins [12].

- Chaperonins (GroEL/GroES in bacteria): These are large, barrel-shaped complexes that provide an isolated compartment for a single protein molecule to fold unimpeded by aggregation-prone interactions in the crowded cytosol [13].

The process of refolding is also a critical step in biotechnology for recovering active recombinant proteins from inclusion bodies—insoluble aggregates formed when proteins are overexpressed in bacterial systems like E. coli [13] [14].

Experimental Protocol: Recovering Active Proteins from Inclusion Bodies

The following is a standard protocol for refolding proteins from inclusion bodies [13] [14]:

- Washing: Isolated inclusion body pellets are washed with buffers containing low concentrations of denaturants (e.g., 1-2 M Urea) and mild detergents (e.g., 1% Triton X-100) to remove impurities like membrane fragments, lipids, and nucleic acids.

- Solubilization and Denaturation: The washed inclusion bodies are dissolved and denatured using a high concentration of denaturants. Common agents include:

- 6 M Guanidine Hydrochloride (GdnHCl)

- 8 M Urea

- Ionic detergents like Sarkosyl or SDS

- A reducing agent (e.g., Dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol) is added to break improper disulfide bonds.

Refolding: This is the most critical step, where the denaturant is removed to allow the protein to adopt its native structure. Key methods include:

- Dilution: The denatured protein solution is rapidly diluted 50- to 100-fold into a refolding buffer. This instantaneously lowers the concentration of denaturant and the protein itself, reducing aggregation. The protein is typically incubated overnight at 4°C to fold [13] [14].

- Dialysis: The denatured protein is placed in a dialysis membrane against a refolding buffer. The denaturant is gradually removed over 1-2 days through diffusion. Step-wise dialysis, with progressively lower denaturant concentrations, can sometimes improve yields by slowing the refolding process [13].

- Chromatographic Methods: Techniques like size-exclusion chromatography can be used to separate the protein from the denaturant rapidly, facilitating refolding at higher concentrations [14].

Purification: The refolded protein is purified using standard chromatographic techniques such as affinity, ion-exchange, or size-exclusion chromatography to isolate the correctly folded, active species.

Table 1: Common Additives in Refolding Buffers and Their Functions

| Additive Type | Examples | Primary Function | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregation Inhibitors | L-Arginine, L-Arginine HCl | Suppress protein aggregation | Interacts with aggregation-prone intermediates, increasing protein solubility without stabilizing the native state [13]. |

| Protein Stabilizers | Glycerol, Sugars (Sorbitol, Trehalose), (NH₄)₂SO₄ | Stabilize the native protein structure | Preferential exclusion from the protein surface, favoring a compact, folded state; can also act as osmolytes [13]. |

| Low Denaturants | 0.5-1 M Urea, 0.5-1 M GdnHCl | Suppress aggregation | At low concentrations, can stabilize folding intermediates and slow down incorrect aggregation pathways [13]. |

| Redox Shuffling Systems | Glutathione (GSH/GSSG), Cysteine/Cystamine | Facilitate correct disulfide bond formation | Provides a redox environment that allows for the breaking and reformation of disulfide bonds until the correct native pairings are achieved [13]. |

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for protein refolding from inclusion bodies.

The Degradation Pathway: Targeted Elimination via Ubiquitin-Proteasome and Lysosomes

When refolding attempts fail, the PQC system flags misfolded proteins for destruction. In eukaryotic cells, the primary routes for degradation are the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the lysosomal pathway [15]. While bacteria lack an identical UPS, they possess analogous ATP-dependent proteases (e.g., Lon, ClpXP, FtsH) that perform a similar function, selectively degrading misfolded proteins.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS)

The UPS is the main pathway for degrading short-lived and soluble misfolded proteins in eukaryotes [15]. Degradation involves a cascade of enzymes:

- E1 (Ubiquitin-activating enzyme): Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner.

- E2 (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme): Accepts the activated ubiquitin from E1.

- E3 (Ubiquitin ligase): Recognizes specific substrate proteins and catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate.

Repeated cycles of this process result in the formation of a polyubiquitin chain on the substrate, predominantly linked through lysine 48 (K48) of ubiquitin. This K48-linked chain is a canonical signal for the proteasome, a large multi-subunit protease complex, which recognizes, unfolds, and degrades the tagged protein into short peptides [15].

Lysosomal Degradation

Lysosomes are responsible for degrading long-lived proteins, insoluble protein aggregates, and entire organelles. Cargo is delivered to lysosomes through several mechanisms [15]:

- Endocytosis: Engulfment of extracellular material and plasma membrane proteins.

- Autophagy: A conserved process where cytoplasmic components, including protein aggregates and damaged organelles, are sequestered within double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes, which subsequently fuse with lysosomes for degradation.

- Phagocytosis: Engulfment of large particles, such as microbial pathogens.

Emerging Technologies: Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD)

The understanding of natural degradation pathways has inspired the development of novel therapeutic strategies, most notably PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) [15].

- PROTAC Mechanism: A PROTAC is a heterobifunctional molecule comprising three parts: a ligand that binds an E3 ubiquitin ligase, a warhead that binds a target Protein of Interest (POI), and a linker connecting them. The PROTAC recruits the E3 ligase to the POI, inducing its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome [15].

- Advantages over Inhibitors: Unlike traditional inhibitors that merely block a protein's activity, PROTACs catalytically destroy the target protein, eliminating all its functions (scaffolding and enzymatic). This can overcome drug resistance caused by target overexpression and can target proteins previously considered "undruggable" [15].

Table 2: Key Components of Protein Degradation Pathways

| Degradation Pathway | Key Components | Primary Substrates | Cellular Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) | E1, E2, E3 Enzymes, Proteasome | Short-lived, soluble misfolded proteins; regulatory proteins [15]. | Fine-tuned regulation of protein half-life; clearance of misfolded proteins. |

| Lysosomal Pathways | Lysosome, Autophagosome, ESCRT Complex | Long-lived proteins, protein aggregates, damaged organelles, extracellular proteins [15]. | Bulk degradation; clearance of large aggregates and cellular debris. |

| Targeted Protein Degradation (PROTAC) | E3 Ligase Ligand, POI-binding Warhead, Linker | Disease-causing proteins targeted for therapeutic degradation [15]. | A therapeutic strategy for induced, targeted protein removal. |

Diagram 2: Major pathways for targeted protein degradation in eukaryotic cells.

Spatial Sequestration: Containment and Asymmetric Segregation

When the refolding and degradation machinery are overwhelmed, such as during severe or chronic stress, cells deploy a third strategy: the spatial sequestration of misfolded proteins and aggregates into specific, defined cellular locations. This containment limits the toxicity of aggregates by preventing them from interfering with essential cellular processes and facilitates their management [12].

Quality Control Sites in Yeast

Studies in yeast have been instrumental in identifying distinct quality control compartments:

- Juxtanuclear Quality Control (JUNQ) / Intranuclear Quality Control (INQ): These are perinuclear or intranuclear sites that contain soluble, ubiquitinated misfolded proteins that are still accessible to the proteasome for degradation. The JUNQ/INQ sequesters proteins damaged by heat stress [12].

- Insoluble Protein Deposit (IPOD): A perivacuolar site that accumulates insoluble, amyloid-like aggregates that are largely resistant to degradation. The IPOD serves as a long-term storage depot for material that cannot be easily cleared [12].

The recruitment of chaperones to protein aggregates is not uniform but depends on the type of proteotoxic stress. For example, the resolution of heat-induced aggregates requires the Hsp40 chaperone Ydj1, while aggregates formed under oxidative stress rely on the peroxiredoxin Tsa1 and a different Hsp40, Sis1 [12]. This indicates that the composition and structure of aggregates differ depending on the stressor.

Asymmetric Segregation and Rejuvenation

A critical function of spatial PQC is its role in cellular aging and rejuvenation. In asymmetrically dividing cells, such as yeast, the PQC system actively sequesters damaged proteins and ensures their retention in the mother cell. This allows the newly formed daughter cell to be born with a pristine, rejuvenated proteome, free from inherited damage [12]. This asymmetric segregation is a key process that delays the manifestation of aging phenotypes across generations.

The Research Toolkit: Key Reagents and Technologies

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for Studying Misfolded Proteins

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Proteins (FPs) [16] | Imaging Reagent | Tagging proteins of interest (e.g., HU for nucleoid, FtsZ for division) for live-cell imaging of localization and dynamics in bacteria. Fast-folding variants (e.g., sfGFP, mCherry) are crucial for accuracy. |

| Chemical Chaperones [13] | Refolding Reagent | Additives like L-Arginine and Glycerol used in refolding buffers to inhibit aggregation and improve the yield of active protein from inclusion bodies. |

| Denaturants [13] [14] | Biochemical Reagent | Urea and Guanidine HCl used to solubilize inclusion bodies by denaturing aggregated proteins into unfolded polypeptide chains. |

| PROTAC Molecules [15] | Degradation Inducer | Heterobifunctional small molecules that recruit a target protein to an E3 ubiquitin ligase, inducing its degradation; a key tool in chemical biology and therapeutics. |

| Model Substrates [12] | Research Model | Misfolding-prone proteins like Ubc9ts (temperature-sensitive) and VHL used to study aggregate formation, sequestration, and clearance in model organisms like yeast. |

| AI Structure Prediction (AlphaFold) [17] [18] | Computational Tool | AI systems like AlphaFold3 predict protein 3D structures and complexes, providing insights into folding and misfolding mechanisms. |

The cellular management of misfolded proteins through refolding, degradation, and sequestration represents an integrated, multi-layered defense network essential for maintaining proteostasis. The PQC system is dynamically tuned, with chaperone requirements shifting based on the nature of the proteotoxic stress [12]. Furthermore, its role extends beyond mere housekeeping; the bacterial PQC network actively shapes evolutionary processes by influencing mutational robustness, epistasis, and navigability of protein sequence space [2] [3].

The deep interplay between these PQC strategies and fundamental cellular processes underscores their importance. Disruptions in PQC are linked to a range of neurodegenerative diseases and aging [12]. Consequently, the strategies outlined here are not only of basic scientific interest but also provide a foundation for therapeutic interventions, as exemplified by the emergence of targeted degradation technologies [15]. Understanding and leveraging these cellular strategies will continue to be a vibrant area of research with profound implications for biotechnology, medicine, and our comprehension of evolutionary dynamics.

The bacterial protein quality control (PQC) network comprises a sophisticated system of chaperones, proteases, and translational machinery that collectively maintain proteome homeostasis (proteostasis) by ensuring proper protein folding, function, and degradation [2] [3]. Far from being merely a housekeeping system, emerging research establishes PQC as a master modulator of molecular evolution that profoundly influences evolutionary dynamics in bacterial populations [2]. This network participates in vital cellular processes and exerts significant influence on organismal development and evolutionary trajectories by shaping the relationship between genotype and phenotype [3]. Specifically, the PQC system functions as a crucial evolutionary mediator by enhancing mutational robustness—the ability to buffer the phenotypic effects of genetic variation—while simultaneously modulating evolvability, the capacity to generate adaptive phenotypic diversity [2]. This review examines the mechanistic bases through which the bacterial PQC network influences molecular evolution, exploring its relevance to contemporary issues in evolutionary biology including epistasis, evolvability, and the navigability of protein sequence space, all within the broader context of protein quality control research in bacterial evolution [2].

The conceptual framework for understanding PQC's evolutionary role bridges multiple physical scales of biological organization, from molecular properties of proteins to organismal fitness [19]. The biophysical fitness landscape concept provides a powerful approach to understanding how PQC bridges the gap between genotype and fitness through the intermediate phenotype of molecular biophysical properties [19]. In this model, sequence variation translates to variation in molecular and systems-level properties of proteins (stability, activity, intracellular abundance), which subsequently maps to organismal fitness effects that ultimately determine the fate of mutations in populations [19]. The PQC network operates at the critical interface of these transitions, directly influencing how mutations affect protein stability and function, thereby shaping the evolutionary trajectories accessible to bacterial populations [2] [19].

Mechanistic Insights: How PQC Components Shape Evolutionary Dynamics

Molecular Chaperones as Buffers and Evolutionary Capacitors

Molecular chaperones, including DnaK and Hsp90, represent fundamental components of the PQC network that facilitate proper protein folding and prevent aggregation [2]. These chaperones function as evolutionary capacitors that enhance mutational robustness by transiently binding to and stabilizing partially misfolded protein variants that would otherwise be degraded or form toxic aggregates [2]. This buffering capacity allows genetic variation to accumulate in a phenotypically silent manner, creating hidden genetic diversity that can be exposed during periods of physiological stress [2]. Experimental evidence demonstrates that the molecular chaperone DnaK serves as a significant source of mutational robustness in bacterial systems [2]. Beyond merely buffering deleterious mutations, chaperones can also influence the navigability of protein sequence space by altering the fitness effects of mutations, thereby shaping both the accessibility of evolutionary paths and the ultimate evolutionary outcomes [2].

The capacitor function of chaperones exhibits dose-dependent effects on evolutionary dynamics, with implications for both adaptive potential and genetic load [2]. At optimal concentrations, chaperones provide sufficient buffering capacity to enable the exploration of novel protein sequences while maintaining proteome integrity [2]. However, supra-optimal chaperone levels might excessively buffer strongly deleterious mutations, potentially increasing genetic load, while suboptimal levels may restrict evolutionary exploration by exposing all but the most conservative mutations to stringent selection [2]. This delicate balance highlights how cellular concentrations of PQC components, themselves subject to regulation and evolutionary pressure, can fundamentally alter evolutionary dynamics by modifying the genotype-phenotype map [2].

Proteases and the Regulation of Genetic Diversity

ATP-dependent proteases such as Lon, ClpXP, and FtsH constitute the degradation arm of the PQC network, systematically removing misfolded or damaged proteins [2]. These proteases play a dual evolutionary role by both constraining and directing phenotypic variation. By eliminating non-functional and potentially toxic misfolded proteins, proteases reduce the phenotypic expression of certain mutations, effectively cleansing the population of potentially deleterious variants [2]. However, this cleansing function also shapes the available mutational landscape by determining which protein variants persist long enough to potentially evolve new functions [2]. The regulated proteolysis of maladapted proteins prevents the accumulation of potentially dominant-negative protein variants that could compromise cellular fitness, while simultaneously creating opportunities for evolutionary innovation by clearing the cellular environment for the emergence and testing of novel protein variants [2].

The balance between chaperones and proteases creates a proteostatic regulation system that tunes the stringency of quality control in response to cellular conditions [2]. Under optimal growth conditions, this system maintains strict quality control, while during stress conditions, the modulation of PQC component expression and activity may permit the temporary relaxation of quality control standards, allowing for the expression of previously buffered genetic variation [2]. This conditional regulation of proteostatic stringency provides a mechanism for tuning evolvability in response to environmental challenges, potentially accelerating adaptation when organisms face novel or stressful conditions [2].

PQC-Mediated Epistasis and Evolutionary Trajectories

Epistasis, the non-additive interaction between mutations, represents a fundamental challenge in predicting evolutionary trajectories [19]. The PQC network serves as a primary source of protein stability-mediated epistasis that shapes the accessible paths in protein sequence space [19]. Empirical studies demonstrate that protein stability represents a prevalent mechanism of intramolecular epistasis, wherein the fitness effect of a mutation depends on the background stability conferred by previous mutations [19]. For example, research on influenza nucleoprotein revealed that evolution was constrained by stability-related epistasis, where acquisition of stabilizing mutations was required prior to obtaining adaptive substitutions that would have been excessively destabilizing in the original background [19].

The PQC network influences these epistatic interactions by determining the functional threshold for protein stability and folding efficiency [2] [19]. Chaperones can mitigate destabilizing effects of mutations, thereby altering the sign and magnitude of epistatic interactions [2]. This PQC-mediated epistasis profoundly affects evolutionary outcomes by determining which mutational pathways are accessible and which evolutionary dead ends [2] [19]. When PQC components buffer destabilizing mutations, they can smooth the fitness landscape by reducing ruggedness caused by stability thresholds, thereby enabling evolutionary exploration of regions of sequence space that would otherwise be inaccessible due to protein instability [2].

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of PQC on Evolutionary Parameters in Bacterial Systems

| Evolutionary Parameter | Effect of PQC | Experimental Evidence | Magnitude of Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutational robustness | Increased buffering of deleterious mutations | DnaK overexpression buffers fitness effects of mutations [2] | 2- to 5-fold reduction in fitness effects observed |

| Protein evolvability | Accelerated evolution of new functions | Chaperones promote folding of alternative conformations [2] | Up to 40% increase in evolutionary rate reported |

| Epistatic interactions | Altered sign and magnitude of epistasis | Stability-mediated epistasis modulated by chaperone activity [19] | Background-dependent effects observed |

| Accessible sequence space | Expansion of neutral networks | PQC enables exploration of destabilizing mutations [2] | Increased connectivity in protein sequence space |

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies for Investigating PQC in Evolution

Quantifying PQC Effects on Protein Evolution Rates

Experimental evolution studies coupled with directed evolution approaches represent powerful methodologies for investigating how PQC components influence molecular evolution [2] [19]. These experiments typically involve propagating bacterial populations under controlled laboratory conditions while manipulating the expression or activity of specific PQC components [2]. The foundational protocol involves: (1) constructing isogenic bacterial strains that differ in the expression level of a specific PQC component (e.g., chaperone overexpression or knockout strains), (2) subjecting these strains to identical evolutionary regimes, which may include constant or fluctuating environments, and (3) quantifying evolutionary outcomes through measures such as fitness trajectories, mutation accumulation rates, and the emergence of novel functions [2].

Detailed methodology for assessing evolutionary rates involves tracking the fixation of mutations in target proteins under different PQC conditions [2]. Researchers typically: (1) introduce a reporter gene expressing a model protein whose evolution can be readily tracked, (2) apply mutagenesis to generate genetic diversity, (3) propagate populations with varying PQC component expression levels, and (4) sequence the target gene at multiple time points to quantify evolutionary changes [2]. Parameters measured include the number of fixed mutations, the distribution of mutation types (synonymous vs. nonsynonymous), and the rate of fitness recovery or adaptation [2]. These experiments have demonstrated that chaperones can accelerate the evolution of new protein functions by enabling the folding of alternative protein conformations that would be inaccessible under stricter proteostatic control [2].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for investigating PQC effects on molecular evolution, integrating genetic manipulation with evolutionary analysis.

Measuring Mutational Robustness and Epistasis

Systematic mutational scanning approaches enable quantitative assessment of how PQC influences mutational robustness and epistasis [19]. The methodology involves: (1) creating comprehensive mutant libraries of a target protein, (2) expressing these variants in bacterial strains with normal versus modulated PQC activity, (3) quantifying the fitness effects of each mutation through growth rate measurements or competitive fitness assays, and (4) analyzing the distribution of fitness effects to determine how PQC alters mutational tolerance [19]. High-throughput approaches utilizing deep mutational scanning employ DNA barcoding and next-generation sequencing to simultaneously track the frequency of thousands of protein variants in pooled competitions, providing comprehensive data on how PQC affects the fitness landscape [19].

For epistasis measurements, researchers employ double-mutant cycle analysis to quantify non-additive interactions between mutations [19]. The protocol involves: (1) constructing all possible single and double mutants for a set of positions in a protein of interest, (2) measuring the fitness or biochemical function of each variant, (3) calculating the expected additive effect versus observed effect for double mutants, and (4) comparing these epistatic interactions in different PQC backgrounds [19]. These experiments have revealed that PQC components can alter epistatic relationships by buffering destabilizing interactions, thereby changing the connectivity in protein sequence space and the accessibility of evolutionary trajectories [19].

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Investigating PQC in Molecular Evolution

| Methodology | Key Procedures | Measured Parameters | Applications in PQC Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental evolution with PQC manipulation | 1. PQC component overexpression/knockout2. Laboratory evolution in controlled environments3. Whole-genome sequencing of evolved populations | 1. Rate of adaptation2. Mutation accumulation patterns3. Fitness trajectories | Quantifying effects of chaperones on evolutionary rates [2] |

| Deep mutational scanning | 1. Saturation mutagenesis of target genes2. Pooled competitive growth assays3. High-throughput sequencing of variant frequencies | 1. Distribution of fitness effects2. Mutational tolerance landscapes3. Protein stability effects | Mapping how PQC alters protein fitness landscapes [19] |

| Double-mutant cycle analysis | 1. Construction of single and double mutants2. Functional assays for all variants3. Calculation of epistatic coefficients | 1. Magnitude and sign of epistasis2. Background dependence of mutational effects3. Stability-mediated epistasis | Determining how PQC modulates epistatic interactions [19] |

| Protein stability and folding assays | 1. Thermal shift assays2. Circular dichroism spectroscopy3. Protease sensitivity assays4. Chaperone binding assays | 1. Melting temperature (Tm)2. Folding kinetics3. Aggregation propensity4. Chaperone client specificity | Linking PQC activity to protein biophysical properties [19] |

Analyzing Fitness Landscapes and Evolutionary Navigability

Biophysical fitness landscape modeling provides a computational framework for integrating empirical data on how PQC influences molecular evolution [19]. This approach involves: (1) measuring the biophysical effects of mutations (e.g., on protein stability and function), (2) determining how these biophysical properties map to cellular fitness, (3) incorporating the moderating effects of PQC components on this mapping, and (4) simulating evolutionary trajectories across the resulting landscape [19]. The resulting models can predict how PQC activity influences the navigability of protein sequence space, including the accessibility of adaptive peaks and the distribution of evolutionary paths [19].

Experimental validation of fitness landscape models employs phylogenetic reconstruction and ancestral sequence resurrection to trace historical evolutionary paths [19]. Researchers: (1) reconstruct ancestral protein sequences using phylogenetic methods, (2) synthesize and characterize these ancestral proteins biophysically, (3) test the functional effects of historical mutations in different ancestral backgrounds, and (4) determine how PQC components would have influenced the fitness effects of these historical substitutions [19]. These approaches have revealed instances where PQC-enabled buffering permitted the accumulation of mutations that subsequently served as stepping stones to novel protein functions, demonstrating how PQC can facilitate evolutionary innovation [2] [19].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Systems for PQC-Evolution Studies

| Research Tool | Specifications and Variants | Experimental Function | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PQC-Modulated Bacterial Strains | - Chaperone overexpression strains (DnaK, GroEL/ES, Hsp90)- Protease knockout mutants (Lon, ClpXP, FtsH)- PQC regulatory element mutants | Provide genetic backgrounds with altered PQC capacity for comparative evolution experiments | Testing effects of chaperone activity on mutation buffering and evolutionary rates [2] |

| Reporter Protein Systems | - Enzymes with easily assayed functions (β-lactamase, DHFR, GFP)- Temperature-sensitive mutants as folding reporters- Aggregation-prone protein variants | Serve as model proteins for tracking evolutionary trajectories and protein folding states | Quantifying how PQC affects distribution of fitness effects across mutational landscapes [19] |

| High-Throughput Mutagenesis Platforms | - Site-saturation mutagenesis libraries- Error-prone PCR generation of random mutants- CRISPR-enabled genome editing for specific mutations | Create genetic diversity for fitness landscape mapping and evolvability assessments | Comprehensive epistasis mapping in different PQC backgrounds [19] |

| Protein Biophysical Characterization Tools | - Thermal shift assay reagents- Circular dichroism spectrometers- Size-exclusion chromatography systems- Intrinsic fluorescence instrumentation | Quantify protein stability, folding状态, and aggregation propensity | Linking PQC activity to protein stability parameters and their fitness consequences [19] |

| Fitness Assay Systems | - Competitive growth measurement setups |

Precisely quantify relative fitness of genetic variants in different PQC contexts | Measuring how PQC alters fitness effects of mutations and evolutionary trajectories [2] [19] |

Integrated Signaling and Evolutionary Pathways

The PQC network operates as an integrated system that senses proteostatic imbalance and coordinates responses that ultimately influence evolutionary dynamics [2]. The core pathway begins with the recognition of non-native protein states by chaperones and proteases, leading to decisions between refolding versus degradation fates for protein variants [2]. These decisions directly impact which mutations are phenotypically expressed and therefore subject to selection, creating a crucial interface between the protein folding environment and evolutionary outcomes [2].

Diagram 2: The PQC network as a mediator between genetic variation and evolutionary outcomes, showing how protein fate decisions influence phenotypic expression and selection.

At the molecular level, the PQC network shapes evolutionary trajectories through protein stability-activity tradeoffs that create complex fitness landscapes [19]. The hierarchical organization of this system begins with direct effects of mutations on protein folding and stability, which are then modulated by chaperone binding and protease susceptibility [2] [19]. These molecular interactions determine protein abundance and function, which subsequently influence cellular fitness and ultimately evolutionary dynamics at the population level [19]. This multi-scale integration explains how PQC can alter evolutionary outcomes by changing the relationship between genetic variation and its phenotypic consequences [2] [19].

The PQC network also interacts with other cellular regulatory systems, including quorum sensing pathways that coordinate population-level behaviors in bacteria [20] [21]. These connections position PQC as a central integrator of intracellular protein homeostasis information with extracellular population density signals [20] [21]. Such integration may create sophisticated feedback systems where social behaviors influence proteostatic stress, which in turn modulates evolutionary dynamics through PQC-mediated effects on genetic variation [20]. This intersection between PQC and bacterial social signaling represents a promising frontier for understanding how proteostasis networks influence evolution in ecologically relevant contexts [20] [21].

Research Implications and Future Directions

The recognition of PQC as a master modulator of molecular evolution carries significant implications for multiple fields, from fundamental evolutionary biology to applied drug development [2]. In therapeutic development, understanding how PQC influences evolutionary dynamics could inform strategies for anticipating and countering antimicrobial resistance evolution [2]. By targeting PQC components that enhance mutational robustness in bacterial pathogens, it might be possible to reduce their evolutionary potential and slow the emergence of resistance [2]. Conversely, enhancing PQC capacity in industrial bacterial strains could accelerate the evolution of desirable traits for biotechnology applications [2].

Future research directions should focus on quantifying PQC effects on evolutionary dynamics in more ecologically realistic environments, including multi-species communities and spatially structured habitats [2] [19]. The integration of single-cell approaches with evolutionary tracking will enable more precise mapping of how PQC heterogeneity within populations creates differential evolutionary outcomes [2]. Additionally, systematic comparative studies across diverse bacterial taxa will reveal how variations in PQC network architecture correspond to differences in evolutionary patterns [2]. These investigations will further solidify our understanding of PQC as a central evolutionary modulator that shapes the fundamental relationship between genotype and phenotype across the bacterial domain [2] [3].

The study of bacterial PQC networks also provides insights that extend beyond microbial evolution, offering testable models for understanding proteostasis-evolution relationships in more complex organisms [2] [3]. The principles emerging from bacterial systems—including the capacitor function of chaperones, the landscape-smoothing effects of proteostatic buffering, and the prevalence of stability-mediated epistasis—likely represent general evolutionary mechanisms operating across the tree of life [2]. As such, the continued investigation of how PQC modulates molecular evolution in bacteria promises to yield fundamental insights into evolutionary processes operating throughout the biosphere [2] [3].

The Impact of PQC on Epistasis and the Navigability of Protein Sequence Space

The study of molecular evolution is fundamentally concerned with the relationship between genotype and phenotype. Within this framework, epistasis—the phenomenon where the effect of one genetic mutation depends on the presence of other mutations—creates a complex, rugged topography in protein sequence space that profoundly influences evolutionary trajectories [22]. The bacterial protein quality control (PQC) network, comprising chaperones, proteases, and translational machinery, serves as a master modulator of this relationship by maintaining proteostasis and shaping the functional outcomes of genetic variation [2] [3]. This technical guide explores the emerging intersection of post-quantum cryptography (PQC) and evolutionary biology, examining how computational frameworks secured against quantum attacks will safeguard the next generation of research into epistasis and sequence space navigability.

The vulnerability of current public-key cryptography to quantum attacks, primarily through Shor's algorithm, presents a critical challenge for the long-term security of biological data [23] [24]. Research in epistasis and protein evolution generates datasets that must remain confidential and integral over decades, creating a pressing need for quantum-resistant cryptographic protection. The recent finalization of the first PQC standards by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) marks a pivotal moment for preparing biological research infrastructure for the quantum era [25] [26]. This whitepaper provides researchers and drug development professionals with the technical foundation for integrating PQC into computational and experimental workflows exploring the PQC network's influence on molecular evolution.

Theoretical Foundations

Epistasis and Protein Sequence Space Navigability

The concept of sequence space provides a multidimensional representation of all possible genotypes, where each point represents a unique sequence and adjacent points differ by a single mutation [22]. The PQC network influences navigation through this space by affecting how amino acid substitutions impact protein folding and function.

- Rugged Topology: Epistasis creates a rugged fitness landscape where the functional effect of a mutation depends critically on its genetic background. This ruggedness constrains evolutionary paths, making some trajectories inaccessible while opening others through permissive mutations [22].

- Intermolecular Epistasis: In complexes such as transcription factors and their DNA binding sites, epistatic interactions across molecular interfaces dictate affinity and specificity. These interactions make the evolution of each molecule contingent upon its partner's evolutionary history [22].

- PQC as an Evolvability Buffer: Bacterial PQC components, particularly chaperones like DnaK, can buffer the effects of mutations, thereby increasing mutational robustness and facilitating the exploration of sequence space that would otherwise be inaccessible [2] [3].

Post-Quantum Cryptography Fundamentals

Post-quantum cryptography refers to cryptographic algorithms designed to be secure against attacks by both classical and quantum computers [23] [24]. Unlike current public-key algorithms that rely on the difficulty of integer factorization or discrete logarithms—problems susceptible to quantum attacks via Shor's algorithm—PQC is based on mathematical problems considered hard for quantum computers to solve.

Table: Core Families of Post-Quantum Cryptographic Algorithms

| Algorithm Family | Mathematical Basis | Security Assumption | Primary Use Cases | NIST Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lattice-based | Learning With Errors (LWE), Short Integer Solution (SIS) | Hardness of worst-case lattice problems | Key establishment (ML-KEM), Digital signatures (ML-DSA) | FIPS 203, FIPS 204 (Standardized) |

| Hash-based | One-way hash functions | Collision resistance of hash functions | Digital signatures (SLH-DSA) | FIPS 205 (Standardized) |

| Code-based | Error-correcting codes | Syndrome decoding problem | Key encapsulation (HQC, McEliece) | Selected for standardization (2025) |

| Multivariate | Systems of multivariate equations | Difficulty of solving nonlinear systems | Digital signatures | Under evaluation |

| Isogeny-based | Isogenies between elliptic curves | Hardness of finding isogenies between curves | Key exchange | Research ongoing after SIDH cryptanalysis |

The transition to PQC is not merely a theoretical concern but an immediate practical necessity. The "harvest now, decrypt later" attack vector, where adversaries collect encrypted data today for decryption once quantum computers become available, poses a direct threat to the long-term confidentiality of sensitive biological research data [23] [26] [27]. Organizations are advised to begin cryptographic inventory assessments and transition planning now, as the migration process will likely take years [27].

PQC-Enabled Methodologies for Epistasis Research

Quantum-Accelerated Epistasis Detection

The detection and characterization of epistatic interactions represents a computationally intensive challenge in genetics, particularly for higher-order interactions beyond pairwise effects. The NeEDL (Network-based Epistasis Detection via Local Search) framework demonstrates how quantum computing techniques can be integrated into epistasis research to overcome these computational barriers [28].

NeEDL leverages a biologically-informed SNP-SNP interaction (SSI) network, where single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are mapped to proteins and connected if they affect the same or functionally associated proteins. This network medicine approach constrains the search space to biologically plausible epistatic interactions, dramatically improving both statistical significance and computational efficiency [28]. The framework employs local search with multi-start and simulated annealing to identify connected subgraphs in the SSI network that show strong statistical association with phenotypes.

Table: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Epistasis Detection Tools

| Tool / Method | Optimal SNP Set Size | Statistical Superiority | Computational Requirements | Biological Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NeEDL | 3-7 SNPs | Markedly outperforms competitors across MLM, K2, and NLL gain metrics [28] | ~1 million CPU hours for 8 diseases | SSI network based on PPI and functional associations |

| MACOED | 2 SNPs | Outperformed by NeEDL on all datasets and metrics [28] | Requires supercomputer with high RAM | Limited biological context |

| LinDen | 2 SNPs | Outperformed by NeEDL on all datasets and metrics [28] | Executable on desktop PCs | Limited biological context |

| Random Sampling | 2+ SNPs | Significantly lower scores than all dedicated tools | Minimal | No biological context |

The integration of quantum computing algorithms within NeEDL provides high-quality initial solutions for the local search, substantially reducing runtime while maintaining biological relevance. This hybrid quantum-classical approach represents the first seamless integration of quantum computing for solving real-world life sciences problems and demonstrates the potential for PQC-secured quantum acceleration in epistasis research [28].

Experimental Protocol for Characterizing Intermolecular Epistasis

To illustrate the experimental workflows that PQC will secure, we present a detailed methodology for characterizing epistasis across molecular interfaces, adapted from studies of transcription factor-DNA binding evolution [22].

Objective: To quantitatively map the joint sequence space of a transcription factor (TF) and its DNA response element (RE) and characterize the epistatic interactions that govern binding affinity and specificity.

Materials and Reagents:

- Recombinant DNA Constructs: Plasmids encoding ancestral and variant TF sequences

- DNA-Binding Assay Components: Radiolabeled or fluorescently-labeled RE probes, gel electrophoresis or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) equipment

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit: For introducing specific point mutations into TF and RE sequences

- Cell-Free Protein Expression System: For in vitro synthesis of TF variants

- Binding Reaction Buffer: Typically containing nonspecific competitor DNA (e.g., poly(dI-dC))

Procedure:

- Sequence Space Definition: Identify all mutational paths between ancestral and derived TF-RE complexes through phylogenetic reconstruction and ancestral sequence resurrection.

- Variant Generation: Using site-directed mutagenesis, create all combinatorial variants of the TF and RE along these mutational paths.

- Binding Affinity Measurement:

- Express and purify each TF variant using cell-free expression systems

- Perform electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) or SPR with each TF-RE combination

- Quantify binding affinity (Kd) through densitometry (EMSA) or direct measurement (SPR)

- Epistasis Calculation:

- For each TF-RE combination, calculate the observed binding affinity

- Compare observed values to expected values under a multiplicative (non-epistatic) model

- Quantify epistasis as the difference between observed and expected log-transformed affinities

- Pathway Analysis: Identify accessible evolutionary paths through sequence space where no intermediate step shows significantly reduced binding affinity.

This experimental workflow generates sensitive functional data that must be securely stored and shared across research collaborations, creating a compelling use case for PQC implementation.

Visualization of Research Workflows

Epistasis Detection via Network-Based Local Search

The following diagram illustrates the NeEDL workflow for detecting epistatic interactions using a network medicine approach with quantum computing acceleration.

Joint TF-RE Sequence Space Mapping

This diagram outlines the experimental protocol for characterizing intermolecular epistasis in transcription factor-DNA response element complexes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Epistasis and Sequence Space Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Application Example | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduces specific point mutations into gene sequences | Generating TF and RE variants along evolutionary paths [22] | Efficiency critical for creating large combinatorial libraries |

| Cell-Free Protein Expression System | In vitro synthesis of protein variants | Producing ancestral and mutant transcription factors [22] | Avoids toxicity issues; enables rapid screening |

| Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) Components | Measures protein-DNA binding affinity | Quantifying TF-RE interaction strengths across sequence space [22] | Provides quantitative Kd values with proper controls |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Instrumentation | Real-time measurement of biomolecular interactions | High-throughput binding kinetics for epistasis calculations [22] | Higher precision but more expensive than EMSA |

| SNP-SNP Interaction (SSI) Network Database | Maps genetic variations to protein interactions and functional associations | Biologically-informed constraint for epistasis detection [28] | Integrates PPI data, functional annotations, and genetic mappings |

| Quantum Computing Simulators | Models quantum algorithms for optimization problems | Generating initial solutions for NeEDL local search [28] | Currently limited to small instances; awaits hardware advancement |

Integration with Bacterial Protein Quality Control Research

The bacterial PQC network serves as a paradigm for understanding how proteostasis influences molecular evolution and epistasis. This network—comprising chaperones, proteases, and translational machinery—directly modulates the genotype-phenotype relationship by affecting protein folding, stability, and degradation [2] [3].

PQC as an Epistatic Buffer: Chaperones like DnaK can buffer the effects of deleterious mutations, effectively altering the epistatic landscape by allowing proteins to tolerate mutations that would otherwise be destabilizing [2] [3]. This buffering capacity expands the navigable regions of protein sequence space and facilitates evolutionary exploration.

Modulation of Evolutionary Trajectories: By influencing which mutations are phenotypically expressed, the PQC network shapes evolutionary trajectories. This effect is particularly relevant for the evolution of molecular complexes, where PQC components can alter the interdependency between interacting molecules [3].

Integration with Research Workflows: Future studies of PQC-mediated epistasis will generate extensive genetic and functional data requiring long-term security. The implementation of PQC ensures that this sensitive research remains protected against emerging quantum computing threats, preserving decades of investment in understanding bacterial evolution and proteostasis.

The convergence of post-quantum cryptography and research into epistasis and protein sequence space represents a critical frontier in evolutionary biology. The rugged topography of sequence space, shaped by pervasive epistasis within and between molecules, constrains evolutionary paths while enabling functional innovation. The bacterial protein quality control network further modulates this relationship by buffering genetic variation and altering evolutionary constraints. As research in this field advances, generating increasingly complex and valuable datasets, the implementation of quantum-resistant cryptographic standards becomes essential for protecting the long-term security and integrity of this work. By adopting PQC standards now, researchers can ensure that their investigations into the fundamental principles of molecular evolution remain secure in the quantum computing era.

Advanced Techniques and Therapeutic Applications in PQC Research

Protein quality control (PQC) systems represent a fundamental biological safeguard, ensuring cellular fitness through the continual monitoring, refolding, or degradation of misfolded and damaged proteins. In Gram-negative bacteria, the periplasmic compartment presents a uniquely challenging environment for PQC, hosting critical processes including nutrient uptake, cell wall metabolism, and antibiotic resistance, yet being subject to variable and occasionally extreme environmental conditions [29]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of periplasmic PQC is not only essential for deciphering bacterial physiology and pathogenesis but also provides a crucial context for studying bacterial evolution. These systems allow pathogens to adapt to hostile environments, including those engineered by host immune responses, and to evolve resistance mechanisms. This technical guide details how in-cell Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has been leveraged to dissect, at an atomic level, the concerted mechanism of periplasmic PQC in live bacteria, offering unprecedented insights into a process central to bacterial survival and evolution.

The Experimental Power of In-Cell NMR

In-cell NMR spectroscopy provides atomic-level resolution of molecular structures and interactions under physiological conditions, filling a critical gap between in vitro biochemical studies and cellular physiology [30]. Unlike traditional structural biology techniques that require purified components or crystalline environments, in-cell NMR allows for the observation of proteins and their complexes within the native, crowded cellular milieu. The technique is exquisitely sensitive to changes in the chemical environment, which are reflected as alterations in chemical shifts, thereby reporting on specific binding interactions with ions, ligands, and other macromolecules, as well as biochemical modifications and conformational changes [30].

Key Methodologies for In-Cell NMR

The acquisition of high-quality in-cell NMR data hinges on specific isotopic labeling strategies and careful sample preparation to distinguish the target protein from the vast background of cellular components.

- Backbone Group Probes: Uniform labeling with

15Nusing15NH4Clas the sole nitrogen source is the most common strategy, detected via1H-15N HSQC(heteronuclear single quantum coherence) spectra. To reduce spectral complexity and background, specific15N-labeled amino acids (e.g., arginine, histidine, lysine) can be incorporated using auxotrophic bacterial strains [30]. - Methyl Group Probes: For larger proteins, selective isotopic labeling of methyl groups (e.g., using

(13C-methyl)-methionine) provides a highly sensitive probe due to the presence of three protons, longer transverse relaxation times, and no exchange with water [30]. - Fluorine Probes: Incorporating

19F-labeled amino acids is highly attractive due to the absence of a natural background in proteins, a large chemical shift range for excellent resolution, and rapid 1D data acquisition capabilities [30]. - Sample Preparation: For bacterial studies, the most straightforward method involves over-expressing the isotopically labeled target protein using an inducible plasmid within the host cells. The intracellular concentration can be finely controlled using tightly regulated promoters (e.g., arabinose

PBAD, rhamnosePRHA), varying induction times, or employing plasmids with different copy numbers [30].

Atomic-Level Dissection of Periplasmic PQC: A Case Study on NDM-1

The periplasm accounts for only 10–20% of the total cell volume yet hosts nearly one-third of the bacterial proteome, making its study by conventional high-resolution techniques particularly challenging [29]. A 2025 study by González et al. utilized in-cell NMR to elucidate the quality control pathway of the metallo-β-lactamase NDM-1, a key enzyme in antibiotic resistance, under conditions of zinc starvation [29] [31].

Experimental System and Workflow

The researchers established a sophisticated dual-plasmid system in Escherichia coli for the independent induction of 15N-labeled, membrane-anchored NDM-1 and the unlabeled proteases Prc and/or DegP. A key aspect was the careful control of protease levels relative to NDM-1 concentration to mimic physiological conditions and avoid cellular toxicity [29]. To trigger PQC, the zinc chelator dipicolinic acid (DPA) was used to strip zinc ions from NDM-1, destabilizing its native structure and promoting its degradation, thereby mimicking the metal depletion faced by bacteria during a host immune response [29].