Ensuring Lot-to-Lot Consistency in Protein Reagents: A Guide for Reproducible Research and Drug Development

This article addresses the critical challenge of lot-to-lot variability in protein reagent production, a major source of irreproducibility in biomedical research and a significant risk in diagnostic and therapeutic development.

Ensuring Lot-to-Lot Consistency in Protein Reagents: A Guide for Reproducible Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of lot-to-lot variability in protein reagent production, a major source of irreproducibility in biomedical research and a significant risk in diagnostic and therapeutic development. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating protein reagent consistency. The content spans from foundational concepts explaining the sources and impacts of variability to methodological approaches for assessing critical quality attributes like active concentration and purity. It offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for both production and analysis, and concludes with rigorous validation and comparative techniques to ensure reagent performance and reliability across multiple lots. By synthesizing current methodologies and best practices, this guide aims to empower scientists to achieve higher standards of data integrity and assay reproducibility.

The Critical Importance of Protein Reagent Consistency: Foundations and Impact

Defining Lot-to-Lot Consistency and Its Impact on Data Reproducibility

In the realm of biomedical research and in vitro diagnostics, the reliability of experimental data is paramount. Lot-to-lot consistency refers to the ability to produce successive batches (or lots) of reagents—such as antibodies, antigens, enzymes, and buffers—with minimal variation in their performance characteristics [1] [2]. This consistency is a critical foundation for data reproducibility, ensuring that results obtained with one batch of reagents can be faithfully replicated using different batches over time [3]. The absence of such consistency, a problem known as lot-to-lot variance (LTLV), introduces substantial uncertainty in reported results and is a significant contributor to the widely acknowledged reproducibility crisis in life sciences research [1] [4]. This guide objectively examines the impact of LTLV and compares methodologies for its evaluation, providing researchers with a framework for assessing reagent consistency.

What is Lot-to-Lot Consistency?

A "lot" represents a specific volume of reagents manufactured from the same raw materials, undergoing identical purification and production processes, and quality-controlled as a single unit [5]. Lot-to-lot consistency means that different production batches of a reagent demonstrate equivalent analytical performance, yielding comparable results for the same sample [6] [5].

The technical performance of immunoassays and other protein-based assays is determined by two key elements: raw materials (accounting for an estimated 70% of performance) and production processes (accounting for 30%) [1]. The production process guarantees the lower limit of kit quality and reproducibility, while the quality of raw materials sets the upper limit for sensitivity and specificity [1]. Inconsistencies in either domain directly lead to LTLV.

Causes and Consequences of Lot-to-Lot Variance

Root Causes of Variance

Lot-to-lot variance arises from multiple factors rooted in the complexity of biological reagents and their manufacturing.

- Quality Fluctuation in Raw Materials: Biological raw materials are inherently variable and difficult to regulate [1].

- Antibodies: Variations in activity, concentration, affinity, purity, and stability between batches are common. Aggregation of antibodies, particularly at high concentrations, is a major issue that can lead to high background signals and inaccurate analyte concentration readings [1].

- Antigens: Inconsistent purity, stability, and aggregation can affect labeling efficiency, reducing specificity and signal strength [1].

- Enzymes: Enzymes like Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) are often purified from natural sources. While purity may be consistent, significant differences in enzymatic activity between lots are frequently observed [1].

- Deviations in Manufacturing Processes: The process of binding antibodies to a solid phase inevitably results in slight differences in the quantity bound from one batch to another, even under controlled conditions [2]. Any changes in buffer recipes, reagent formulation, or conjugation efficiency can also introduce variance [1].

- Instability of Calibrators and Controls: Calibrators and quality control materials that are unstable or have a short shelf-life can contribute to LTLV if they are not standardized against a stable master calibrator [1].

Impact on Data Reproducibility and Clinical/Research Outcomes

The consequences of LTLV are not merely theoretical; they have tangible, negative impacts on both research and clinical practice.

- Research Reproducibility Crisis: Poor-quality proteins and peptides are a leading cause of irreproducible experimental data. One analysis attributed 36.1% of the cost of irreproducible preclinical research in the U.S.—approximately \$10.4 billion annually—directly to biological reagents and reference materials [3] [4].

- Clinical Consequences: In a clinical setting, undetected LTLV can lead to misinterpretation of patient results. Documented cases include:

- HbA1c: A reagent lot change caused an average 0.5% increase in patient results, potentially leading to misdiagnosis of diabetes [2].

- PSA: Falsely elevated Prostate-Specific Antigen results from a specific reagent lot caused undue concern for post-prostatectomy patients, as it suggested cancer recurrence [2].

- Cardiac Troponin I (cTnI): Variance in an immunoassay for cTnI, a key biomarker for diagnosing myocardial infarction, could lead to wrong diagnoses, inappropriate treatment, and fatal outcomes for patients [1].

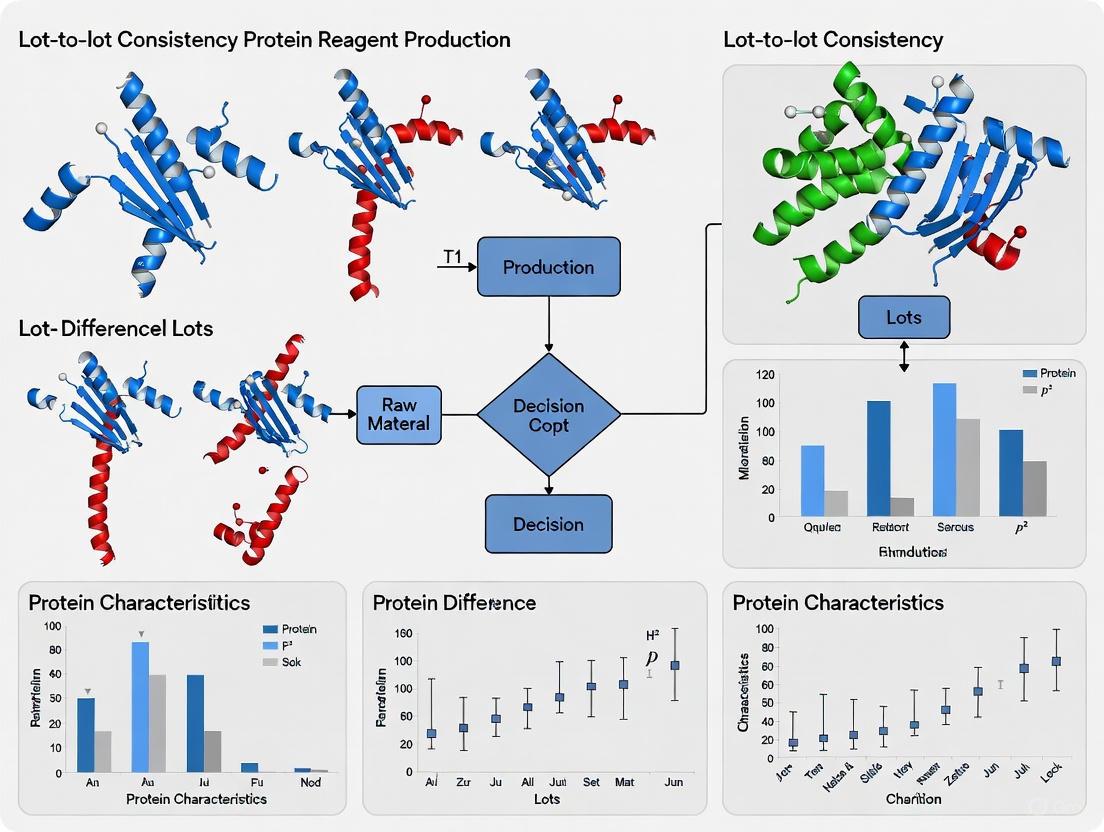

The diagram below illustrates the primary causes of LTLV and their direct consequences on data and outcomes.

Quantitative Evidence: Documented Variability in Immunoassays

Empirical studies across various diagnostic platforms consistently demonstrate the presence and extent of LTLV. The following table summarizes data from a study analyzing reagent lot-to-lot comparability for five common immunoassay items over ten months [7].

Table 1: Documented Lot-to-Lot Variation in Common Immunoassays [7]

| Analyte | Platform | Number of Lot Changes Evaluated | % Difference in Mean Control Values (Range) | Maximum Observed Difference:SD Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFP (α-fetoprotein) | ADVIA Centaur | 5 | 0.1% to 17.5% | 4.37 |

| Ferritin | ADVIA Centaur | 5 | 1.0% to 18.6% | 4.39 |

| CA19-9 | Roche Cobas E 411 | 5 | 0.6% to 14.3% | 2.43 |

| HBsAg (Quantitative) | Architect i2000 | 5 | 0.6% to 16.2% | 1.64 |

| Anti-HBs | Architect i2000 | 5 | 0.1% to 17.7% | 4.16 |

This data reveals extensive variability, with percent differences between lots exceeding 15% for some analytes. The Difference to Standard Deviation (D:SD) ratio is another critical metric; a high value (e.g., >4.0 for AFP, Ferritin, and Anti-HBs) indicates that the shift between lots is large compared to the assay's usual run-to-run variation, highlighting a significant change in performance [7].

Evaluating Lot-to-Lot Consistency: Experimental Protocols and Acceptance Criteria

For laboratories and researchers, implementing a robust protocol to evaluate new reagent lots is essential for maintaining data integrity.

Standard Experimental Protocol for Lot Verification

The following workflow, derived from clinical laboratory best practices and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines, outlines the core steps for validating a new reagent lot [2] [8].

Detailed Methodologies:

- Define Acceptance Criteria: Prior to testing, establish the maximum allowable difference between the old and new lots. These criteria should be based on clinical requirements, biological variation, or professional recommendations, not arbitrary percentages [2] [8]. For example, a tighter acceptance limit is required for tests with narrow clinical decision thresholds.

- Select Patient Samples: Use fresh or properly stored native patient samples that span the analytical range of the assay, including concentrations near critical medical decision points. A minimum of 5-20 samples is recommended, with more samples providing greater statistical power [2] [8]. It is crucial to avoid relying solely on commercial quality control (QC) or external quality assurance (EQA) materials, as they often lack commutability—they may not behave the same way as patient samples when reagent lots change, leading to incorrect acceptance or rejection of a new lot [2] [8].

- Concurrent Testing: Analyze all selected samples in a single run using both the current (old) and new reagent lots on the same instrument and, ideally, on the same day to minimize pre-analytical variables [2] [7].

- Statistical Analysis: Perform statistical analysis on the paired results. Common methods include:

- Percent Difference: Calculate the % difference for each sample pair and ensure the mean or a specified percentage of individual differences falls within the pre-defined acceptance criteria [7] [8].

- Linear Regression and Correlation: Plot the results from the new lot (y-axis) against the old lot (x-axis). A correlation coefficient (r) close to 1.0 (e.g., R² between 0.85-1.00) and a slope between 0.85-1.15 are often considered acceptable, indicating a strong linear relationship with minimal proportional bias [6].

- Decision Point: Based on the analysis, decide whether to accept the new lot for routine use, reject it and contact the manufacturer, or conduct further investigation [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Materials and Methods for QC

Implementing rigorous quality control for protein reagents requires specific tools and techniques. The following table details essential solutions and methods used to verify reagent consistency [1] [3] [9].

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for Quality Control of Protein Reagents

| Tool Category | Specific Technique / Solution | Primary Function in QC |

|---|---|---|

| Purity Assessment | SDS-PAGE, Capillary Electrophoresis (CE), Reversed-Phase HPLC (RPLC) | Detects contaminants, protein fragments, and proteolysis to ensure reagent purity. |

| Identity Confirmation | Mass Spectrometry (MS) - "Bottom-up" or "Top-down" | Verifies protein identity and correct amino acid sequence, and checks for post-translational modifications. |

| Homogeneity & Aggregation Analysis | Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), SEC coupled to Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS), Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Assesses oligomeric state, detects protein aggregates, and ensures sample monodispersity. |

| Functional Activity Assay | Enzyme Activity Assays, Ligand Binding Assays | Measures the biological or functional activity of the reagent, confirming it is not just present but active. |

| Concentration Measurement | UV Spectrophotometry (A280), Colorimetric Assays (e.g., BCA) | Accurately determines protein concentration, which is critical for assay standardization. |

Strategies for Mitigation and Future Directions

While laboratories can monitor LTLV, the most effective strategies involve actions by manufacturers and the adoption of innovative technologies.

- For Manufacturers: Adhere to stringent quality control during production, use master calibrators that are stable and freeze-dried for longevity, and establish raw material specifications that include not just purity but also functional activity [1] [6]. Sourcing recombinant antibodies over hybridoma-derived ones can improve consistency, provided the purification process ensures high purity [1].

- For the Scientific Community: Adopt guidelines for reporting protein quality control data in publications. Proposed minimal guidelines include reporting the complete protein sequence, expression and purification conditions, and results from purity and homogeneity tests (e.g., SDS-PAGE, SEC) [3]. This practice increases confidence in published data.

- Emerging Alternatives: Precision-engineered synthetic controls, such as engineered cell mimics, offer a promising path to reduce biological variability. These mimics demonstrate significantly lower lot-to-lot variability (CVs often below 5%) compared to biological controls like PBMCs (CVs ranging from 1.6% to 36.6%) and exhibit superior stability, with shelf lives of up to 18 months [4].

- Advanced Monitoring: Laboratories should implement moving average algorithms (also known as Bull's algorithm) to monitor long-term drift in patient results that may not be detected by individual lot-to-lot comparisons [8]. This technique can identify small, cumulative shifts over multiple reagent lot changes.

Defining and ensuring lot-to-lot consistency is not a peripheral quality control issue but a central pillar of reproducible science and reliable clinical diagnostics. As evidenced, LTLV is a pervasive problem with documented impacts on assay performance, leading to increased costs and potential for erroneous conclusions. By understanding its causes, implementing rigorous experimental validation protocols using patient samples, and utilizing a defined scientist's toolkit for quality control, researchers and laboratory professionals can significantly mitigate these risks. The path toward greater reproducibility requires a concerted effort from both reagent manufacturers, through improved production and QC processes, and the end-users, through diligent evaluation and the adoption of standardized reporting and monitoring practices.

In the pursuit of scientific discovery and drug development, consistency in experimental reagents is often assumed rather than verified. However, lot-to-lot variation in protein biological reagents represents a hidden crisis that undermines research reproducibility, inflates costs, and compromises therapeutic development. Protein biological reagents—including antibodies, recombinant proteins, and assay kits—form the foundation of modern biological research and diagnostic development. The global market for these essential tools was valued at USD 6.12 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach USD 10.51 billion by 2032, exhibiting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.2% [10]. This expanding market reflects the critical importance of these reagents, yet within this growth lies a significant challenge: inconsistent reagent quality that costs the U.S. research community alone an estimated $350 million annually in wasted resources [11].

This comparison guide examines the financial and scientific consequences of reagent variability through systematic evaluation of detection methods, validation protocols, and correction strategies. By framing this analysis within the broader thesis of lot-to-lot consistency evaluation in protein reagent production, we provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with evidence-based frameworks for assessing and mitigating variability in their experimental systems. The following sections present quantitative comparisons of reagent performance, detailed experimental methodologies for consistency testing, and visualization of critical pathways for managing reagent variability—all aimed at empowering the research community to demand and implement higher standards in reagent production and validation.

Financial Impact: Quantifying the Cost of Inconsistency

The economic burden of reagent variability extends far beyond the initial purchase price, affecting research efficiency, drug development timelines, and clinical outcomes. The table below summarizes the key financial impacts identified through market analysis and research waste studies.

Table 1: Financial Consequences of Reagent Variability

| Impact Category | Scale/Magnitude | Primary Contributors |

|---|---|---|

| Annual Research Waste | $350 million (U.S. alone) [11] | Failed experiments, irreproducible studies |

| Global Market Value | $6.12 billion (2024) to $10.51 billion (2032) [10] | Rising demand amid consistency challenges |

| Pharmaceutical R&D Investment | $86.6 billion in preclinical research [10] | Extended timelines due to unreliable reagents |

| Life Science Research Allocation | 10-15% allocated to biological reagents [10] | Repeat experiments, validation studies |

| Protein Reagents Segment | ~30% of biological reagents budget [10] | Premium pricing for quality-controlled products |

The cumulative financial impact of reagent variability manifests most visibly in preclinical research, where the poor quality of commercially available protein reagents has been identified as a primary cause of low reproducibility [11]. In regulated bioanalysis, where protein-based reagents serve critical roles in pharmacokinetic assays, biomarker tests, and drug release assays, inconsistencies can lead to misleading results with direct clinical consequences [11]. This problem is particularly acute in the pharmaceutical industry, which invested $86.6 billion in preclinical research activities, all dependent on reliable protein reagents [10].

Beyond direct research costs, reagent variability creates hidden expenses through extended project timelines, failed technology transfers, and delayed drug approvals. The diagnostic sector faces similar challenges, with documented cases of lot-to-lot variation affecting clinical interpretations and potentially leading to inappropriate patient management [2] [8]. As the protein engineering market expands—projected to grow from $3.5 billion in 2024 to $7.8 billion by 2030 [12]—the economic imperative for addressing reagent consistency becomes increasingly urgent.

Scientific Consequences: How Variability Compromises Research

Analytical Challenges Across Research Domains

The scientific implications of reagent variability extend across basic research, translational studies, and clinical applications. The table below compares the manifestations and consequences of lot-to-lot variation across different scientific domains.

Table 2: Scientific Consequences of Reagent Variability Across Research Domains

| Research Domain | Manifestation of Variability | Impact on Data Integrity |

|---|---|---|

| Proteomics Research | Batch effects in MS-based proteomics [13] | Compromised multi-batch data integration, false biomarker identification |

| Clinical Diagnostics | Shifts in analyte quantification (e.g., IGF-1, PSA) [2] [14] | Incorrect clinical interpretations, potential misdiagnosis |

| Drug Development | Altered bioactivity measurements in critical reagents [11] | Inaccurate potency assessments, flawed efficacy conclusions |

| Biomarker Discovery | Inconsistent protein detection and quantification [13] | Irreproducible biomarker validation, failed translational efforts |

| Basic Research | Uncontrolled experimental variables [15] | Questionable findings, limited reproducibility between labs |

In proteomics research, batch effects introduced by reagent variability are particularly problematic for mass spectrometry-based studies. Recent benchmarking studies demonstrate that unwanted technical variations caused by differences in labs, pipelines, or batches are "notorious in MS-based proteomics data" and can challenge the reproducibility and reliability of studies [13]. These batch effects become especially problematic in large-scale cohort studies where data integration across multiple batches is required.

In clinical diagnostics, documented cases highlight the direct patient care implications of reagent variability. One study documented how undetected lot-to-lot variation in insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) reagents led to spuriously high results that didn't correlate with clinical presentation [14]. Similarly, lot-to-lot variation in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) reagents produced falsely elevated results that could have prompted unnecessary invasive procedures for patients who had previously undergone radical prostatectomy [2] [14].

Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Variability

At the molecular level, reagent variability stems from several fundamental sources in protein production and characterization:

Structural Misfolding: Recent research on protein phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) has revealed that specific misfolding mechanisms, particularly "non-covalent lasso entanglement" where protein segments become improperly intertwined, can create long-lived misfolded states that resist correction [15]. These structural anomalies directly impact protein function and consistency between production lots.

Inadequate Characterization: Traditional protein quantification methods (e.g., absorbance at 280 nm, Bradford assay, BCA assay) measure total protein concentration rather than the active portion capable of binding to intended targets [11]. This critical limitation means that lots with identical total protein concentrations may have dramatically different functional activities.

Post-translational Modifications: Recombinant protein production in biological systems introduces inherent variability in post-translational modifications that affect protein function but may not be detected by standard quality control measures [11].

The following diagram illustrates the molecular mechanisms and experimental consequences of protein reagent variability:

Experimental Comparison: Assessing Reagent Consistency Protocols

Methodologies for Evaluating Lot-to-Lot Consistency

Robust assessment of reagent consistency requires systematic experimental approaches. The following section details key methodologies and protocols for evaluating lot-to-lot variation, drawn from clinical chemistry practices and proteomics research.

Table 3: Experimental Protocols for Assessing Reagent Lot-to-Lot Consistency

| Methodology | Protocol Description | Key Metrics | Statistical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Sample Comparison | Parallel testing of 5-20 patient samples with old and new reagent lots [8] | Percent difference, bias estimation | Power analysis, clinical acceptability limits |

| CLSI Guideline Protocol | Standardized approach for consistency evaluation [8] | Mean difference, standard deviation | Predetermined performance specifications |

| Moving Averages Monitoring | Real-time tracking of average patient values [8] [14] | Population mean shifts | Trend analysis, statistical process control |

| Batch-Effect Correction Benchmarking | Comparison of correction at precursor, peptide, and protein levels [13] | Coefficient of variation, signal-to-noise ratio | Multiple testing correction, effect size estimation |

| Calibration-Free Concentration Analysis | SPR-based active concentration measurement [11] | Active protein concentration | Diffusion coefficient calculations |

The patient sample comparison approach represents the gold standard in clinical laboratory practice for evaluating new reagent lots. The protocol involves: (1) establishing acceptable performance criteria based on clinical requirements; (2) selecting patient samples encompassing the reportable range of the assay, with emphasis on medical decision limits; (3) testing samples with both reagent lots using the same instrument and operator; and (4) statistical analysis of paired results against acceptance criteria [8]. This method directly addresses the critical limitation of quality control (QC) materials, which often demonstrate poor commutability with patient samples [2].

For proteomics research, recent benchmarking studies have evaluated batch-effect correction at different data levels (precursor, peptide, and protein) using real-world multi-batch data from reference materials and simulated datasets [13]. These studies employ a range of batch-effect correction algorithms (ComBat, Median centering, Ratio, RUV-III-C, Harmony, WaveICA2.0, and NormAE) combined with quantification methods (MaxLFQ, TopPep3, and iBAQ) to assess correction robustness using both feature-based and sample-based metrics [13].

Comparative Performance of Consistency Assessment Methods

The following experimental data, synthesized from multiple studies, compares the effectiveness of different approaches for detecting and managing reagent variability:

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Reagent Consistency Assessment Methods

| Assessment Method | Detection Sensitivity | Implementation Complexity | Limitations | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QC Material Validation | Low (40.9% discordance with patient results) [2] | Low | Poor commutability with patient samples | Initial screening only |

| Patient Sample Comparison | High (direct clinical relevance) [8] | Moderate | Sample availability, time requirements | High-risk tests (e.g., hCG, troponin) |

| Moving Averages | Moderate for cumulative drift [8] | High (IT infrastructure) | Requires high test volume | Large clinical laboratories |

| Protein-Level Batch Correction | High for proteomics data [13] | High (computational) | Requires specialized expertise | Large-scale proteomics studies |

| Calibration-Free Concentration Analysis | High for active concentration [11] | Moderate (instrument-dependent) | Requires specialized equipment | Critical reagent characterization |

The moving averages approach, first proposed in 1965, represents a powerful method for detecting long-term drift in reagent performance [8]. This technique monitors in real-time the average patient value for a given analyte by continuously calculating means within a moving window of successive patient results [8]. The method is particularly valuable for identifying cumulative shifts between reagent lots that might not be detected through traditional comparison protocols.

For research applications, protein-level batch-effect correction has emerged as the most robust strategy for managing variability in mass spectrometry-based proteomics. A comprehensive benchmarking study demonstrated that protein-level correction outperformed precursor- and peptide-level approaches across multiple quantification methods and batch-effect correction algorithms [13]. The MaxLFQ-Ratio combination showed particularly superior prediction performance when applied to large-scale data from 1,431 plasma samples of type 2 diabetes patients [13].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting appropriate reagent consistency assessment methods:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Managing Reagent Variability

Based on the comprehensive analysis of reagent variability challenges and solutions, the following table summarizes key research reagent solutions and methodologies that should form part of every researcher's toolkit for managing consistency:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Managing Variability

| Tool/Solution | Primary Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Standardized benchmarks for cross-lot comparison [13] | Availability, commutability with test samples |

| Batch-Effect Correction Algorithms | Computational removal of technical variations [13] | Compatibility with data type, computational resources |

| Calibration-Free Concentration Analysis | Measurement of active protein concentration [11] | SPR instrument requirement, method validation |

| Moving Averages Software | Detection of long-term drift in results [8] | Test volume requirements, IT infrastructure |

| Structured Validation Protocols | Standardized assessment of new reagent lots [8] [14] | Resource allocation, statistical expertise |

| Multi-Protein Detection Kits | Simultaneous detection of multiple protein targets [16] | Platform compatibility, antibody validation |

The implementation of calibration-free concentration analysis (CFCA) represents a particularly advanced solution for characterizing critical protein reagents. This surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based method specifically measures the active protein concentration in a sample by leveraging binding under partially mass-transport limited conditions [11]. Unlike traditional methods that measure total protein, CFCA directly quantifies the functional protein, overcoming a fundamental limitation in reagent characterization.

For computational approaches to batch effects, recent benchmarking has identified several high-performing algorithms. Ratio-based methods have demonstrated particular effectiveness, especially when batch effects are confounded with biological groups of interest [13]. The Harmony algorithm, originally developed for single-cell RNA sequencing data, has shown promise for proteomics applications when applied at the protein level [13].

The financial and scientific costs of reagent variability present significant challenges to research progress and patient care. With an estimated $350 million in annual waste in the U.S. alone due to poor quality biological reagents [11], and documented cases of clinical harm resulting from undetected lot-to-lot variation [2] [14], the need for improved consistency is clear.

The experimental comparisons presented in this guide demonstrate that protein-level batch-effect correction provides the most robust approach for managing variability in proteomics research [13], while patient-based comparison methods and moving averages monitoring offer the greatest protection against clinically significant shifts in diagnostic settings [8]. Emerging technologies like calibration-free concentration analysis address fundamental limitations in traditional protein quantification by measuring active rather than total protein concentration [11].

As the global market for protein detection and quantification continues its rapid growth—projected to reach $3.41 billion by 2029 [16]—the research community must advocate for and implement higher standards in reagent production, characterization, and validation. Through adoption of the rigorous comparison methods and innovative solutions detailed in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can mitigate the high costs of variability and advance the reproducibility and reliability of protein-based research and diagnostics.

In the field of biopharmaceuticals and research reagent production, lot-to-lot consistency is a critical metric for quality. Recombinant protein production is inherently complex, with variability arising from multiple stages of the development pipeline. For scientists and drug development professionals, understanding and controlling these sources of variability is essential for producing reliable, high-quality reagents and therapeutics. This guide objectively compares the primary expression systems and identifies the key factors influencing product consistency, drawing on experimental data and established protocols.

Expression Host Systems: A Comparative Analysis

The choice of expression host is a primary determinant of a recombinant protein's fundamental characteristics, including its post-translational modifications (PTMs), solubility, and ultimately, its biological activity [17]. Different host systems possess inherent strengths and weaknesses, making them more or less suitable for specific applications and contributing significantly to variability.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of common expression systems based on industry adoption and approved therapeutics:

Table 1: Comparison of Recombinant Protein Expression Host Systems

| Expression Host | Common Examples | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Prevalence in Approved Therapeutics* | Ideal Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammalian Cells | CHO, HEK293, NS0, Sp2/0 | Human-like PTMs (glycosylation), complex protein folding | High cost, slow growth, complex media requirements | ~84% (52 of 62 recently approved) [17] | Therapeutic proteins, complex glycoproteins |

| E. coli | BL21 derivatives | Rapid growth, high yield, low cost, easy scale-up | Lack of complex PTMs, formation of inclusion bodies | 5 of 62 recently approved [17] | Non-glycosylated proteins, research reagents |

| Yeast | P. pastoris, S. cerevisiae | Easy scale-up, some PTMs, eukaryotic secretion | Non-human, hyper-mannosylated glycosylation | 4 of 62 recently approved [17] | Industrial enzymes, antigens |

| Insect Cells | Sf9, Sf21 | Baculovirus-driven high expression, eukaryotic processing | Glycosylation differs from mammalian systems | Not listed in top hosts for recent approvals [17] | Research proteins, virus-like particles |

| Transgenic Plants/Animals | --- | Potential for very large-scale production | Regulatory challenges, public perception | 1 of 62 recently approved [17] | Specific high-volume products |

Data based on analysis of new biopharmaceutical active ingredients marketed in the 3-4 years prior to 2019 [17].

Key Experimental Protocols in Process Development

Robust experimental design is required to identify and control variability. The following protocols are central to process optimization.

Medium Optimization Workflow

Culture medium is a significant cost driver and a major source of variability, accounting for up to 80% of direct production costs [18]. A structured, multi-stage approach is used for optimization.

Diagram 1: Medium Optimization Workflow

- Planning Stage: Define objectives and response variables (e.g., protein yield, quality attributes like glycosylation patterns). Select medium components (factors) and their concentration ranges (levels) to test [18].

- Screening Stage: Identify components with statistically significant impacts on responses. High-throughput systems (e.g., 96-well microtiter plates) and Design of Experiments (DoE) are used to test multiple factors with minimal experimental runs [17] [18].

- Modeling Stage: Establish mathematical relationships between medium components and outcomes. Techniques include:

- Optimization Stage: Refine component concentrations using models. Methods like Bayesian optimization or genetic algorithms pinpoint the optimal formulation [18].

- Validation Stage: Confirm the optimized medium's performance in larger-scale bioreactors to ensure scalability and robustness [18].

Protocol for Recombinant Antibody Production

Recombinant antibodies exemplify the pursuit of perfect consistency. Their production involves a defined, in vitro process that eliminates biological variability from animal immunization [19].

Diagram 2: Recombinant Antibody Production

- Obtain Protein Sequence: The antibody of interest is sequenced using technologies like whole transcriptome shotgun sequencing or mass spectrometry (typically a 4-5 week process) [19].

- Design and Order Gene Fragments: Gene fragments encoding the antibody's heavy and light chains are designed and synthesized based on the protein sequence [19].

- Cloning into Plasmids: The gene fragments are cloned into parent plasmids, which act as vectors for gene expression in mammalian cells [19].

- Transfection: Plasmids are transfected into a host cell line, such as human HEK293 suspension cells, which then express and secrete the antibody [19].

- Purification: Antibodies are purified from the culture supernatant using affinity chromatography, typically with Protein A Sepharose beads that bind the antibody's Fc region [19].

Quantitative Data and Variability Analysis

Quantitative data is essential for objectively comparing variability across different production systems and parameters.

Table 2: Quantifying Variability and Its Impact

| Parameter / System | Quantitative Measure | Impact on Variability / Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Medium Cost | Up to 80% of direct production cost [18] | Major driver of economic variability; optimization is critical. |

| Recombinant vs. Hybridoma | Sequence-defined production [19] | Eliminates genetic drift and instability of hybridomas, ensuring superior batch-to-batch consistency. |

| Host System Preference | 84% of recent approved therapeutics from mammalian cells [17] | Highlights industry reliance on systems capable of complex PTMs for therapeutics. |

| Protein Quantification | Median correlation of 0.98 between technical replicates [20] | Demonstrates high reproducibility of LC-MS/MS for quantifying protein abundance, a key variability metric. |

| AI/ML in Optimization | Enables modeling of complex, non-linear interactions [18] | Reduces experimental runs and time to identify optimal, robust conditions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following tools and reagents are fundamental for controlling variability in recombinant protein production research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Controlling Variability

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Controlling Variability |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Bioreactors | Enable parallel screening of cultivation parameters (pH, temperature, feeding) in microliter-to-milliliter volumes, identifying optimal conditions faster [17]. |

| Chemically Defined Media | Eliminates lot-to-lot variability inherent in complex raw materials (e.g., plant hydrolysates) by using precise, known chemical compositions [18]. |

| Affinity Chromatography Resins | Provide highly specific and reproducible purification, critical for isolating the target protein from host cell proteins and other impurities. Example: Protein A Sepharose [19]. |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | The gold standard for quantitative proteomics, used to precisely measure protein abundance, identify PTMs, and monitor product quality attributes across batches [20]. |

| Gene-Editing Tools | Used for host cell engineering to create stable, high-producing cell lines with humanized glycosylation patterns, reducing heterogeneity in critical quality attributes [17]. |

The pursuit of lot-to-lot consistency in recombinant protein production is a multi-faceted challenge addressed through strategic host system selection and rigorous process control. While mammalian cells remain dominant for therapeutic applications requiring complex PTMs, microbial systems offer efficient alternatives for simpler proteins. The data demonstrates that variability is most effectively minimized by adopting a holistic approach: utilizing defined recombinant systems like those for antibodies, implementing structured optimization workflows for critical cost and variability drivers like culture medium, and leveraging advanced analytical tools for quality control. By systematically addressing these key sources of variability, researchers and manufacturers can ensure the production of highly consistent and reliable protein reagents essential for both research and drug development.

For researchers and drug development professionals, lot-to-lot variability in protein reagents represents a significant challenge that can compromise experimental reproducibility and derail development pipelines. A Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) is defined as a physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological property or characteristic that must be within an appropriate limit, range, or distribution to ensure the desired product quality [21]. For protein reagents, establishing a framework for CQA assessment is fundamental to ensuring lot-to-lot consistency, as these attributes directly impact the accuracy and reliability of experimental data in preclinical and clinical development [22] [23].

The central thesis of this guide is that moving beyond traditional total protein concentration measurements to function-based active concentration assays is pivotal for achieving true lot-to-lot consistency. This article provides a structured framework for this assessment, comparing analytical methods and providing experimental protocols to empower scientists to make informed decisions about their critical reagents.

The Core Challenge: Lot-to-Lot Variability in Protein Reagents

Protein reagents, often recombinantly produced, are susceptible to variations during production and purification. These differences manifest as structural integrity issues and variations in bioactive purity between production lots [23]. Even with extensive purification, protein lots often retain some contaminants and/or partially degraded material.

Traditional protein concentration determination methods like the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay, Bradford assay, or A280 measure the total protein in a sample and cannot effectively distinguish between the natively folded protein of interest and partially/fully denatured protein or contaminants [23]. This is a critical shortcoming, as studies quantifying the immunoreactive fraction of purified monoclonal antibodies have reported active concentrations ranging from 35% to 85% of the total protein concentration, with significant lot-to-lot variability [23]. This fundamental mismatch between total protein and active protein concentration is a primary source of experimental variability.

Comparative Analysis of Protein Quantification Methods

Selecting the appropriate analytical method is crucial for accurate CQA assessment. The table below compares common techniques for evaluating protein concentration and quality.

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Quantification and Quality Assessment Methods

| Method | Mechanism of Action | Sensitivity and Effective Range | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradford Assay | Binds specific amino acids and protein tertiary structures; color change from brown to blue [24] | 1 µg/mL to 1.5 mg/mL [24] | Rapid; useful when accuracy is not crucial [24] | High protein-to-protein variation; not compatible with detergents [24] |

| BCA Method | Cu²⁺ reduced to Cu⁺ by proteins at high pH; BCA chelates Cu⁺ forming purple complexes [24] | 0.5 µg/mL to 1.2 mg/mL [24] | Compatible with detergents, chaotropes, and organic solvents [24] | Not compatible with reducing agents; sample must be read within 10 minutes [24] |

| UV Absorption (A280) | Peptide bond absorption; tryptophan and tyrosine absorption [24] | 10 µg/mL to 50 µg/mL or 50 µg/mL to 2 mg/mL [24] | Nondestructive; low cost [24] | Sensitivity depends on aromatic amino acid content [24] |

| Quant-iT / Qubit Protein Assay | Binds to detergent coating on proteins and hydrophobic regions; unbound dye is nonfluorescent [24] | 0.5 to 4 µg in a 200 µL assay volume [24] | High sensitivity; little protein-to-protein variation; compatible with salts, solvents [24] | Not compatible with detergents [24] |

| Calibration-Free Concentration Analysis (CFCA) | Measures binding-capable analyte using mass transport limitation principles in SPR [23] | 0.5–50 nM [23] | Quantifies active, binding-competent fraction; high precision [23] | Requires specialized SPR instrumentation; complex setup [23] |

| SPR-Based Relative Binding Activity | Incorporates both binding affinity (KD) and binding response (Rmax) [25] | Method-dependent | Characterizes overall binding activity level; detects affinity and capacity changes [25] | Requires antibody-antigen system and SPR instrumentation [25] |

A Framework for CQA Assessment: Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Method 1: Calibration-Free Concentration Analysis (CFCA)

CFCA is a surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based method that specifically quantifies the concentration of a protein that is capable of binding to its ligand, providing a direct measurement of the active concentration rather than the total concentration [23].

Experimental Protocol for CFCA:

- Ligand Immobilization: Saturate an SPR sensor chip (e.g., CM5, ProteinA, or ProteinG) with a monoclonal antibody (mAb) specific to your protein of interest. ProteinG chips are often preferred for robust antibody capture [23].

- Analyte Injection: Inject a diluted series of the recombinant protein calibrator (analyte) at a defined flow rate. The initial concentration should start at approximately 40-50 nM, with dilutions down to 2-5 nM [23].

- System Conditions: Ensure the system is at least partially mass-transport-limited, a key requirement for CFCA modeling [23].

- Data Analysis: The SPR software (e.g., Biacore T200 Evaluation software) kinetically models the diffusion and binding of the analyte. The calculated bulk concentration represents the epitope-specific active concentration of your protein reagent [23].

Application and Impact: A pilot study on three batches of recombinant soluble LAG3 (sLAG3) demonstrated that defining the reagents by their CFCA-derived active concentration decreased immunoassay lot-to-lot coefficients of variation (CVs) by over 600% compared to using the total protein concentration, dramatically improving consistency [23].

Method 2: SPR-Based Relative Binding Activity

This method provides a more comprehensive view of functional integrity by combining assessments of binding strength and capacity [25].

Experimental Protocol for SPR-Based Relative Binding Activity:

- Antibody Capture: Immobilize the antibody of interest on an SPR sensor chip.

- Kinetic Analysis: Perform standard SPR binding kinetics analysis by injecting antigen over the captured antibody to determine the association rate constant (ka), dissociation rate constant (kd), equilibrium dissociation constant (KD), and maximum binding response (Rmax) [25].

- Data Normalization and Calculation:

- Calculate Relative Rmax: Normalize the Rmax of the test sample by its capture level, then divide by the normalized Rmax of a standard reference. This reflects the relative binding capacity.

- Calculate Relative KD: Divide the KD of the standard reference by the KD of the test sample. This represents the relative binding strength.

- Calculate Relative Binding Activity: Multiply Relative Rmax by Relative KD. This final value characterizes the overall binding activity level of the test sample relative to the reference [25].

Application and Impact: This method enables precise characterization in stability studies. For example, it can identify specific degradation products like Asp isomerization or Asn deamidation in complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) as potential CQAs by correlating their occurrence with measurable reductions in relative binding activity [25].

The following workflow visualizes the strategic process for applying these methods in a CQA assessment framework.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A robust CQA assessment requires specific reagents and tools. The following table details key materials and their functions in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CQA Assessment

| Reagent / Material | Function in CQA Assessment | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) System (e.g., Biacore T200) | Label-free analysis of biomolecular interactions to determine active concentration, binding kinetics, and relative binding activity [23] [25] | The core instrument for CFCA and relative binding activity methods; requires specific sensor chips [23]. |

| SPR Sensor Chips (CM5, ProteinA, ProteinG) | Surfaces for immobilizing ligands (e.g., antibodies) for interaction analysis [23] | ProteinG chips offer robust antibody capture but suitability depends on the antibody [23]. |

| Reference mAb (e.g., NISTmAb) | Used for system calibration and standardization to ensure inter-laboratory comparability [23] | Critical for assay qualification and validating measurement accuracy [22] [23]. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, TCEP) | Maintain sulfhydryl groups in reduced state; prevent spurious disulfide bond formation during protein analysis [26] | TCEP is odorless and more stable than DTT; preferred for storage. DTT is stronger and used for protein purification [26]. |

| Chromatography Systems (SEC-HPLC) | Assess protein aggregation, fragmentation, and purity based on size and charge [25] | Identifies variants and process-related impurities that may impact quality [25] [21]. |

| Mass Spectrometry Systems | Detailed characterization of post-translational modifications (e.g., deamidation, oxidation) [25] | Identifies and quantifies specific molecular attributes that can be potential CQAs [25]. |

Ensuring lot-to-lot consistency for protein reagents is not merely a quality control check but a fundamental component of robust scientific research and drug development. The framework presented here—prioritizing functional activity assessments like CFCA and SPR-based relative binding activity over traditional total protein methods—enables researchers to identify true CQAs that predict in-assay performance. Developing and validating these assays early in the product development process leads to better decision-making and greater confidence that observed effects are reproducible [22]. By adopting this proactive, measurement-assured approach, scientists and drug development professionals can significantly reduce variability, enhance data comparability, and streamline the path from discovery to clinical application.

In both research and diagnostic laboratories, the integrity of data—and by extension, clinical decision-making—depends heavily on the reagents used. Variability in antibody binding, staining intensity, and background signal can compromise accuracy and necessitate repeat testing, drawing out workflows and increasing costs. Analyte specific reagents (ASRs) represent a category of regulated reagents defined by the FDA as "antibodies, receptor proteins, ligands, nucleic acid sequences, and similar materials that, through specific binding or chemical reactions, identify and quantify specific analytes within biological specimens" [27]. These reagents serve as the fundamental building blocks of Laboratory-Developed Tests (LDTs) and are subject to specific regulatory requirements that distinguish them from research-grade reagents [27].

The broader thesis on evaluating lot-to-lot consistency in protein reagent production research finds direct application in the regulatory context of ASRs. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the regulatory landscape governing these reagents is essential for developing robust, reproducible assays that can transition smoothly from research to clinical application. This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of ASRs against alternative reagent types within the framework of regulatory requirements, providing experimental data and methodologies relevant to evaluating reagent consistency.

Regulatory Framework for ASRs and Related Reagents

ASR Classification and Requirements

ASRs are actively regulated by the FDA under 21 CFR 864.4020 [27]. The majority are classified as Class I medical devices and are regulated under the FDA's current good manufacturing practices (cGMP) as outlined in 21 CFR Part 820, with additional requirements for labeling, sale, distribution, and use under 21 CFR 809.10(e) and 21 CFR 809.30 [27]. For higher-risk applications, such as blood banking, donor screening, and some infectious disease testing, ASRs may be classified as Class II or Class III medical devices, which carry additional regulatory requirements [27].

While not required by the FDA, ASR manufacturers often seek ISO 13485:2016 certification and participate in the Medical Device Single Audit Program (MDSAP) to align with international standards and further ensure product quality and regulatory compliance [27]. This represents a significantly higher regulatory burden compared to research-grade reagents.

Comparison with Other Reagent Categories

ASRs occupy a distinct regulatory space between Research Use Only (RUO) reagents and fully-regulated in vitro diagnostics (IVDs). The following table summarizes key differences:

Table 1: Regulatory Comparison of Reagent Types

| Reagent Category | Intended Use | Regulatory Status | Manufacturing Requirements | Performance Claims |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analyte Specific Reagents (ASRs) | Building blocks for LDTs in CLIA-certified labs [27] | Class I, II, or III medical device [27] | 21 CFR Part 820 (cGMP) [27] | No performance claims permitted; must include "Analyte Specific Reagent" labeling [27] |

| Research Use Only (RUO) | Basic and applied research [27] | Not subject to device regulations [27] | No specific requirements | "For Research Use Only" labeling; not for diagnostic procedures [27] |

| General Purpose Reagents (GPRs) | General laboratory application for specimen preparation/examination [28] | Class I medical device [28] | 510(k) exempt, GMP exempt (with exceptions) [28] | Not labeled for specific diagnostic applications [28] |

| In Vitro Diagnostics (IVDs) | Complete diagnostic test systems [29] | Class I, II, or III medical devices [29] | 21 CFR Part 820; premarket notification/approval [29] | Full analytical/clinical performance claims permitted [29] |

Recent Regulatory Developments

The regulatory landscape for LDTs (which utilize ASRs) continues to evolve. The FDA's Final Rule issued in May 2024 aimed to expand oversight of LDTs by explicitly including them in the definition of IVD products [29]. However, in a significant development, a federal court blocked this rule in April 2025, vacating the FDA's planned regulatory oversight for LDTs [30]. Despite this ruling, ASRs themselves remain regulated by the FDA, and LDTs continue to be governed by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) [30].

Comparative Performance Analysis: ASRs vs. Alternatives

Evaluating Lot-to-Lot Consistency

Lot-to-lot variance (LTLV) presents a significant challenge in immunoassays, negatively affecting accuracy, precision, and specificity, leading to considerable uncertainty in reported results [1]. One study investigating LTLV highlighted that 70% of an immunoassay's performance is attributed to the quality of raw materials, while the remaining 30% is ascribed to the production process [1].

Experimental data demonstrates how subtle differences in reagent quality can significantly impact assay performance. In one investigation comparing a monoclonal antibody sourced from hybridoma versus an otherwise identical recombinant version, researchers observed substantial performance deviations despite identical amino acid sequences [1]:

Table 2: Impact of Antibody Source on Assay Performance

| Parameter | Hybridoma Antibody | Recombinant Antibody | Percent Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Signals (RLU) | 493,180 | 412,901 | -19.4% |

| Background (RLU) | 1,518 | 1,339 | -13.2% |

| Sensitivity (IC50) | 0.41 nM | 0.59 nM | +43.9% |

Analysis revealed that while the recombinant antibody's size exclusion chromatography (SEC-HPLC) purity was approximately 98.7%, capillary electrophoresis sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis (CE-SDS) exposed nearly 13% impurity, primarily single light chains (LC), combinations of two heavy chains and one light chain (2H1L), two heavy chains (2H), and nonglycosylated IgG [1]. These impurities caused reduced sensitivity and maximal signal, demonstrating how manufacturing processes and quality controls critically impact reagent performance.

Methodologies for Assessing Reagent Quality

Experimental Protocol: Purity and Impurity Analysis

Size Exclusion Chromatography with High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (SEC-HPLC)

- Purpose: Assess protein aggregation, fragmentation, and overall purity

- Methodology: Separate molecules based on hydrodynamic volume using aqueous mobile phase and porous stationary phase; compare elution profiles against standards

- Acceptance Criteria: Typically >95% monomeric protein for critical reagents

Capillary Electrophoresis Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (CE-SDS)

- Purpose: Detect charge variants, degradation products, and impurity profiles not visible via SEC-HPLC

- Methodology: Separate proteins based on hydrodynamic size and charge under denaturing conditions; enables detection of fragments, clipped species, and mispaired chains

- Data Interpretation: Quantify percentage of main peak versus impurity peaks (e.g., free light chains, nonglycosylated antibodies)

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

- Purpose: Evaluate protein purity and molecular weight

- Methodology: Separate proteins by molecular weight under denaturing conditions; visualize with Coomassie brilliant blue or silver staining

- Applications: Quick assessment of purity and identification of contaminating proteins

For ASRs, manufacturers must employ these and other robust quality control systems, standardize manufacturing protocols, and maintain comprehensive documentation, including certificates of analysis and technical data sheets [27]. This directly translates to fewer test failures, reduced recalibration needs, and more consistent diagnostic interpretations compared to RUO reagents.

Computational Assessment of Protein Properties

Computational methods provide additional tools for evaluating reagent consistency, particularly for protein-based ASRs. pKa prediction methods enable researchers to assess ionization constants of titratable groups in biomolecules, which strongly influence protein-ligand binding, solubility, and structural stability [31].

Table 3: Comparison of High-Throughput pKa Prediction Methods

| Method | Approach | RMSE (pKa units) | Correlation (R²) | Utility for Protein Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepKa | Machine learning | ~0.76 | ~0.45 | Consistent performance across residue types [31] |

| PROPKA3 | Empirical | ~0.8-0.9 | ~0.4 | Fast, accessible predictions [31] |

| H++ | Macroscopic physics-based (Poisson-Boltzmann) | ~0.8-1.0 | ~0.3-0.4 | Consideration of electrostatic environments [31] |

| DelPhiPKa | Macroscopic physics-based (Poisson-Boltzmann) | ~0.9-1.1 | ~0.3 | Gaussian-smoothed potentials [31] |

| Consensus (Averaging) | Combination of best empirical predictors | 0.76 | 0.45 | Improved transferability and accuracy [31] |

A comprehensive benchmark study evaluated seven popular pKa predictors on a curated set of 408 measured protein residue pKa shifts from the pKa database (PKAD) [31]. While no method dramatically outperformed null hypotheses, several demonstrated utility for protein engineering applications, with consensus approaches providing improved accuracy [31].

Experimental Protocol: pKa Prediction Workflow

Protein Structure Preparation

- Obtain protein structure from PDB or generate via homology modeling

- Add missing hydrogen atoms and optimize side-chain conformations

- Ensure proper protonation states of non-titratable residues

Method Selection and Execution

- Select appropriate pKa prediction method(s) based on target residues and accuracy requirements

- For high-throughput screening, consider faster empirical methods (PROPKA, DeepKa)

- For detailed mechanism studies, employ physics-based methods (DelPhiPKa, H++)

Data Analysis and Validation

- Compare predicted pKa shifts against experimental values when available

- Identify residues with significant pKa deviations from reference values

- Assess potential impact on protein stability, binding, and function

These computational approaches complement experimental methods in characterizing protein reagents and predicting lot-to-lot variability arising from sequence or structural differences.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and methodologies used in evaluating and ensuring quality for regulated reagents:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Quality Assessment

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application in Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| SEC-HPLC | Separates molecules by size | Detects aggregates and fragments in protein reagents [1] |

| CE-SDS | Separates proteins by size and charge under denaturing conditions | Identifies impurity profiles (light/heavy chain variants) [1] |

| Reference Standards | Well-characterized materials for comparison | Provides benchmark for evaluating lot-to-lot consistency [1] |

| Stability Chambers | Control temperature and humidity | Assesses reagent stability under various storage conditions [27] |

| pKa Prediction Software | Calculates ionization constants | Predicts pH-dependent behavior and stability of protein reagents [31] |

| Antibody Characterization Kits | Standardized assessment of binding properties | Evaluates affinity, specificity, and cross-reactivity [27] |

Regulatory Workflow and Quality Considerations

The relationship between regulatory requirements, manufacturing controls, and experimental characterization can be visualized as an integrated workflow:

Key quality considerations for ASRs include clone specificity, which determines which epitope the antibody recognizes, and buffer formulation, whose components (stabilizers, preservatives, proteins) can influence staining quality, instrument compatibility, and assay performance [27]. Laboratories must verify whether the buffer is compatible with their intended assay and won't interfere with downstream steps [27].

For laboratories developing LDTs, validation of test performance using selected ASRs for parameters such as accuracy, precision, sensitivity, and specificity remains essential, regardless of the evolving LDT regulatory landscape [27]. High-quality reagents, combined with deliberate integration and proper validation, provide a strong foundation for maintaining compliance and ensuring reproducible results [27].

ASRs occupy a distinct position in the regulatory ecosystem, requiring more rigorous manufacturing controls and quality assurance than RUO reagents but offering greater consistency and traceability. The comparative data presented demonstrates that while all protein reagents face challenges with lot-to-lot variance, ASRs' requirements for cGMP manufacturing, comprehensive documentation, and robust quality control systems provide measurable benefits in assay consistency and reliability.

For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting appropriate reagent categories requires careful consideration of the intended application, regulatory requirements, and need for lot-to-lot consistency. ASRs provide a critical foundation for developing robust LDTs and facilitating the transition from research to clinical application, particularly when coupled with appropriate characterization methodologies and quality assessment protocols.

Methodologies for Assessing Protein Reagent Quality and Consistency

In biological research and drug development, protein-based reagents are indispensable tools. For decades, scientists have relied on total protein quantification methods like absorbance at 280 nm, bicinchoninic acid (BCA), and Bradford assays to standardize their experiments. However, these conventional approaches harbor a critical flaw: they measure the total quantity of protein in a sample without distinguishing between functionally active molecules and inactive counterparts. This limitation becomes particularly problematic when working with recombinant proteins, which often contain variable proportions of misfolded, denatured, or otherwise inactive species that escape detection by total protein measurements [11].

The distinction between total and active concentration is not merely academic—it has profound implications for experimental reproducibility and reliability. Traditional methods cannot detect variability in the structural integrity and bioactive purity between production lots of a reagent protein [23]. Consequently, researchers may normalize experiments based on total protein concentration only to obtain inconsistent results due to undetected differences in the actual active fraction. This hidden variable contributes significantly to the reproducibility crisis in biological sciences, with poor reagent quality costing an estimated $350 million annually in the United States alone [11].

This guide examines the critical need for active concentration measurement, comparing traditional and emerging methodologies through experimental data. By focusing on the context of lot-to-lot consistency in protein reagent production, we provide researchers with the framework needed to transition beyond total protein quantification toward more reliable functional characterization of their reagents.

Methodological Comparison: From Traditional to Innovative Approaches

The Limitations of Traditional Protein Quantification

Conventional protein quantification methods share a common principle: they measure bulk protein content without discerning functional status. The Bradford, BCA, and Lowry assays all rely on colorimetric signals correlated with total protein quantity, making them susceptible to interference from non-target proteins and chemical contaminants [32]. Particularly for transmembrane proteins, which pose additional challenges due to their integration into lipid bilayers, these methods significantly overestimate functional concentration compared to target-specific assays like ELISA [32].

The fundamental weakness of these approaches lies in their inability to account for the active portion of a protein preparation—the fraction capable of binding to its intended biological target. This limitation becomes critically important when using recombinant proteins as critical reagents in ligand binding assays, cell-based assays, or diagnostic applications [11]. While purity analysis techniques like SDS-PAGE and SEC-HPLC provide some quality assessment, they offer little insight into the actual functional fraction of a protein reagent [11].

Emerging Solutions for Active Concentration Measurement

Immunoassay-Based Approaches

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) present a target-specific solution for quantifying proteins in complex mixtures. Unlike conventional methods that detect all proteins present, immunoassays leverage antigen-antibody interactions to specifically quantify the target protein of interest [32]. The development of a universal indirect ELISA for Na,K-ATPase (NKA) demonstrates this advantage, effectively quantifying the transmembrane protein despite the presence of heterogeneous non-target proteins that confounded traditional methods [32].

Research reveals the dramatic overestimation possible with traditional methods: Lowry, BCA, and Bradford assays all yielded significantly higher apparent concentrations for NKA compared to ELISA, leading to substantial variation in subsequent functional assays [32]. When reactions were prepared using ELISA-determined concentrations, data variation was consistently reduced, highlighting the practical impact of accurate active concentration measurement on experimental reproducibility.

Calibration-Free Concentration Analysis (CFCA)

Calibration-free concentration analysis represents a technological leap in active protein quantification. This surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based method directly measures the active concentration of a protein by leveraging binding under partially mass-transport-limited conditions [23] [33]. CFCA quantifies only those protein species capable of binding to a specific ligand, effectively ignoring inactive or misfolded molecules that contribute to total protein measurements but not to function [11].

The experimental workflow involves immobilizing a high density of ligand on an SPR sensor chip, then flowing diluted analyte at multiple flow rates to create a partially mass-transport-limited system where binding rate depends on active analyte concentration [11]. By modeling the binding data with known diffusion coefficients and molecular weights, CFCA calculates active concentration without requiring a standard curve [33]. This approach has demonstrated remarkable utility in reducing lot-to-lot variability, decreasing coefficients of variation in immunoassays by over 600% compared to total protein concentration normalization [23].

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Quantification Methods

| Method | Principle | Measures | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradford/BCA/Lowry | Colorimetric reaction with proteins | Total protein | Inexpensive, rapid, simple | Cannot distinguish active from inactive protein; susceptible to interference |

| A280 Absorbance | UV absorption by aromatic residues | Total protein | Non-destructive, no reagents required | Dependent on amino acid composition; confounded by contaminants |

| ELISA | Antigen-antibody binding | Specific target protein | Target-specific; high sensitivity | Requires specific antibodies; may not reflect functional activity |

| CFCA | SPR under mass-transport limitation | Active concentration | Direct functional measurement; no standard curve required | Requires specialized instrumentation; knowledge of diffusion coefficient |

Experimental Evidence: Quantifying the Impact on Data Reliability

Case Study: Overcoming Lot-to-Lot Variability in sLAG3

A compelling demonstration of active concentration measurement comes from research on recombinant soluble lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (sLAG3), where CFCA was employed to address significant lot-to-lot variability [23]. Three batches of sLAG3, which appeared fairly pure by SDS-PAGE with calculated purities of 76.7-87.2% by SEC-HPLC, showed remarkably different active concentrations when measured by CFCA. The percent activities of these lots were considerably lower than the HPLC-measured purities and varied substantially between production batches [23].

When sLAG3 lots were defined by their total protein concentrations, the resulting kinetic binding parameters displayed unacceptable variability. However, when the same reagents were normalized by their active concentrations as determined by CFCA, consistency in reported binding parameters improved dramatically [23]. This single adjustment decreased immunoassay lot-to-lot coefficients of variation by over 600%, demonstrating that the total concentration of a protein reagent is not the ideal metric for correlating in-assay signals between lots [23].

Impact on Transmembrane Protein Studies

Research on Na,K-ATPase (NKA) highlights how traditional methods fail particularly with complex protein targets. When comparing conventional quantification methods with a newly developed ELISA for NKA, researchers found that Lowry, BCA, and Bradford assays all significantly overestimated the functional concentration of this transmembrane protein [32]. This overestimation stemmed from the samples containing a heterogeneous mix of proteins, with substantial amounts of non-target proteins contributing to the signal in conventional assays but not to the functional pool of NKA.

The practical consequences emerged when applying these protein concentrations to in vitro assays: reactions prepared using concentrations determined from the ELISA showed consistently lower variation compared to those using conventional quantification methods [32]. This finding underscores how inaccurate concentration determination propagates error through downstream applications, potentially compromising experimental conclusions.

Table 2: Experimental Demonstration of Method-Dependent Variability

| Experimental System | Traditional Method | Active Concentration Method | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| sLAG3 binding assays | BCA/Bradford normalization | CFCA normalization | >600% reduction in lot-to-lot CV; consistent kinetic parameters |

| Na,K-ATPase functional assays | Lowry/BCA/Bradford | Target-specific ELISA | Lower variation in assay results; accurate reaction stoichiometry |

| Protein reagent characterization | A280 absorbance and SEC-HPLC | CFCA active concentration | Revealed 35-85% active fraction range not detectable by purity assays |

Practical Implementation: Methodologies and Protocols

Implementing Calibration-Free Concentration Analysis

The CFCA method requires an SPR system such as a Biacore T200 and follows a standardized protocol [23]:

Ligand Immobilization: Load the monoclonal antibody of interest onto a Protein G-saturated surface to achieve high ligand density. Alternatively, amine-couple the ligand to a CM5 chip.

Analyte Injection: Inject diluted biomarker at multiple concentrations across two different flow rates. The dilution series typically starts at 40-50 nM, with the lower end around 2-5 nM.

System Validation: Ensure the system meets quality controls, including trace signal intensity, linearity, and a fit with QC ratio greater than 0.3.

Data Analysis: Fit binding data using known parameters including the diffusion coefficient, molecular weight of the analyte, and flow cell dimensions to calculate active concentration.

The critical success factors include using a partially mass-transport-limited system, accurate determination of the analyte's diffusion coefficient, and maintaining consistent ligand activity throughout the experiment [11].

Development of Target-Specific ELISA for Transmembrane Proteins

For transmembrane proteins like Na,K-ATPase, developing a specific ELISA provides an accessible alternative for functional quantification [32]:

Antibody Selection: Choose a commercially available primary antibody with broad cross-reactivity across species when studying homologs.

Standard Preparation: Develop a method for producing relative standards by lyophilizing an aliquot of the protein being measured. This allows the ELISA to be adapted to any protein type and source.

Assay Format: Implement an indirect ELISA format where the primary antibody does not require labeling, detected instead by a standard secondary antibody.

Validation: Compare ELISA results with conventional methods to establish the degree of overestimation from non-target proteins in heterogeneous samples.

This approach overcomes the particular challenges posed by transmembrane proteins, whose integration into membranes limits accessibility to dyes and reagents used in conventional assays [32].

Diagram: Method selection directly impacts functional assay reliability through quantification accuracy

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of active concentration measurement requires specific reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for reliable protein characterization:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Active Concentration Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SPR Instrumentation | Enables CFCA measurements | Systems like Biacore T200 with protein A/G chips for ligand capture |

| Protein G Surfaces | Immobilization of capture antibodies | Creates high-density ligand surfaces for mass-transport limitation |

| Specific Antibodies | Target recognition in CFCA or ELISA | Critical for defining which epitope is being measured for activity |

| Reference Standards | Method calibration and normalization | Lyophilized protein aliquots provide consistent relative standards |

| Mass Spectrometry | Integrity verification | Confirms primary structure and detects modifications affecting activity |

| Dynamic Light Scattering | Aggregation assessment | Detects soluble aggregates that affect active concentration |

The evidence presented demonstrates that active concentration measurement represents a paradigm shift in protein reagent characterization. While traditional methods provide information about total protein quantity, they fail to deliver the critical insight needed for reproducible science: the functional fraction of a protein preparation. Methods like CFCA and target-specific ELISA directly address this limitation by quantifying only those protein molecules capable of participating in the biological interactions of interest.

The implications for lot-to-lot consistency are profound. By adopting active concentration measurement, researchers can significantly reduce the hidden variability that plagues protein-based assays, potentially decreasing lot-to-lot coefficients of variation by over 600% [23]. This approach moves beyond the assumption that purity analysis or total protein concentration adequately characterizes reagent quality, instead directly measuring the parameter most relevant to experimental success: functional activity.

As the scientific community continues to address challenges of reproducibility in biological research, embracing active concentration measurement represents a critical step forward. The tools and methodologies now exist to transition beyond total protein quantification toward a more rigorous standard of protein reagent characterization—one that acknowledges the fundamental distinction between the presence of a protein and its functional capacity.

Calibration-Free Concentration Analysis (CFCA) with SPR for Direct Active Protein Quantification

In biological research and drug development, protein-based reagents are indispensable tools. However, a fundamental challenge plagues their reliability: traditional protein quantification methods measure total protein concentration, failing to distinguish between functionally active molecules and inactive or misfolded counterparts [11]. This limitation is a primary contributor to lot-to-lot variance (LTLV), a significant problem costing an estimated $350 million USD annually in the US alone due to wasted research and development efforts [11]. Calibration-Free Concentration Analysis (CFCA) using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) technology addresses this core issue by directly measuring the active concentration of a protein sample—the fraction capable of binding its intended target [11] [23]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of CFCA against traditional methods, detailing its principles, experimental protocols, and its pivotal role in ensuring reagent consistency for critical research and bioanalytical applications.

Principles of CFCA: Moving Beyond Total Protein Measurement