Bacterial Protein Degradation Strategies: From Proteolytic Systems to Advanced Recombinant Protein Production

This article provides a comprehensive overview of protein degradation in bacterial hosts, a critical challenge in biotechnology and therapeutic protein development.

Bacterial Protein Degradation Strategies: From Proteolytic Systems to Advanced Recombinant Protein Production

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of protein degradation in bacterial hosts, a critical challenge in biotechnology and therapeutic protein development. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of bacterial proteolysis, details current and emerging methodologies to mitigate degradation, offers troubleshooting and optimization protocols, and presents comparative analyses of validation techniques. The content synthesizes recent advances to guide the design of robust expression systems for stable, high-yield protein production.

Understanding the Enemy: The Biology of Bacterial Proteolysis and Degradation Pathways

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Question 1: My recombinant protein is being degraded in E. coli despite using protease-deficient strains. What could be the cause, and how can I troubleshoot this? Answer: Protease-deficient strains (e.g., BL21(DE3) Δlon ΔompT) only remove specific major proteases. Residual degradation often points to other ATP-dependent (e.g., ClpXP, ClpAP, FtsH, HslUV) or ATP-independent (e.g., DegP, proteasome-like complexes in Mycobacterium) systems. Troubleshooting steps:

- Check Growth Conditions: Reduce growth temperature (25-30°C) post-induction to slow overall proteolysis.

- Optimize Induction: Use lower inducer concentrations (e.g., 0.1-0.5 mM IPTG) to prevent inclusion body formation, which can trigger stress responses and upregulate proteases.

- Buffer Screen: Ensure your lysis and purification buffers contain appropriate protease inhibitor cocktails. Critical Note: EDTA (chelates Mg2+) inhibits ATP-dependent proteases like FtsH and Lon, but requires Mg2+-free buffers.

- Co-express Chaperones: Co-expression of chaperones (e.g., GroEL/GroES, DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE) can improve folding, reducing the presentation of unstructured regions to proteases.

Question 2: How do I determine if the degradation of my protein of interest is ATP-dependent in vivo? Answer: Perform a simple cellular ATP depletion assay. Protocol: In Vivo ATP Depletion Assay

- Induce expression of your target protein in your bacterial host.

- At mid-log phase, split the culture. Treat one aliquot with 20 mM Sodium Azide (a respiratory chain inhibitor) and 50 mM 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose (a glycolytic inhibitor) for 30-60 minutes to deplete ATP. The other aliquot serves as a control.

- Halt protein synthesis by adding chloramphenicol (200 µg/mL).

- Take samples at time points (0, 15, 30, 60 min), lyse cells, and analyze target protein levels via immunoblotting.

- Interpretation: If degradation is halted or slowed in the ATP-depleted sample, the process is likely mediated by an ATP-dependent protease system.

Question 3: My tagged purification shows a "ladder" of bands on SDS-PAGE, suggesting progressive degradation from one terminus. How can I identify the protease responsible? Answer: This pattern is characteristic of processive degradation. Systematic genetic and inhibitor-based analysis is required.

- Terminus Identification: Use an N-terminal and a C-terminal affinity tag (e.g., His6-tag on opposite ends) in separate constructs. Loss of one tag signal in the ladder identifies the degradation entry point.

- Genetic Screening: Transform your expression construct into a panel of isogenic protease knockout strains (e.g., ΔclpP, ΔclpX, Δlon, ΔhslV, ΔftsH) and compare degradation patterns.

- Inhibitor Profiling: Use specific, cell-permeable inhibitors if available (e.g., ADEP antibiotics activate ClpP, leading to uncontrolled degradation; specific peptide inhibitors for ClpP are under development).

Question 4: What are the best experimental controls when studying a protein's degradation by a specific protease (e.g., ClpXP) in vitro? Answer: Robust controls are essential to confirm protease-specific activity. Protocol: In Vitro Degradation Assay Controls

- Negative Control 1: Omit ATP (for ATP-dependent systems) or use a non-hydrolyzable ATP analogue (e.g., ATPγS).

- Negative Control 2: Use a catalytically dead protease mutant (e.g., ClpP S97A).

- Negative Control 3: Include a non-substrate protein of similar size.

- Positive Control: Include a known, well-characterized substrate for the protease (e.g., SsrA-tagged GFP for ClpXP).

- Reaction Setup: Perform assays in optimized buffer (e.g., 25 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 5-10 mM ATP). Monitor degradation over time by SDS-PAGE or loss of fluorescence for fluorescent substrates.

Quantitative Comparison of Major Bacterial Proteolytic Systems

Table 1: Core ATP-Dependent Protease Complexes

| Protease Complex | Core Components (Gene) | ATPase/Unfoldase | Proteolytic Chamber | Primary Target Signals | Key Cellular Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lon (La) | lon | AAA+ module integrated | Serine protease domain | Misfolded proteins, specific regulators (SulA, RcsA) | Stress response, protein quality control |

| ClpAP | clpA, clpP | ClpA (AAA+) | ClpP (Serine) | SsrA tag, specific native substrates | General turnover, regulated degradation |

| ClpXP | clpX, clpP | ClpX (AAA+) | ClpP (Serine) | SsrA tag, specific substrates (RpoS, CtrA) | Cell cycle, stress response, quality control |

| FtsH | ftsH | AAA+ module integrated | Zinc-metalloprotease domain | Membrane proteins, cytoplasmic regulators | Membrane protein quality control, homeostasis |

| HslUV | hslU, hslV | HslU (AAA+) | HslV (Threonine) | Misfolded proteins, SulA | Heat shock response, degradation of specific regulators |

Table 2: Major ATP-Independent Proteases & Peptidases

| Protease | Class/Gene | Active Site | Primary Function | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DegP (HtrA) | Serine Protease (degP) | Serine | Peripheral quality control, stress response | Chaperone and protease activity; activated by misfolded proteins |

| Proteasome (Mycobacterium) | Threonine Protease (prcBA, mmp) | Threonine | Pup-tagged protein degradation | ATP-dependent for unfolding, but proteolysis is ATP-independent; essential for virulence |

| C-terminal Processing Proteases | e.g., Tsp (prc) | Serine | Trim C-terminal tails, degrade SsrA-tagged proteins | Periplasmic; processive exopeptidase |

| OmpT | Outer Membrane Protease (ompT) | Aspartic | Cleaves between dibasic residues | Surface protease; can cleave recombinant proteins during lysis |

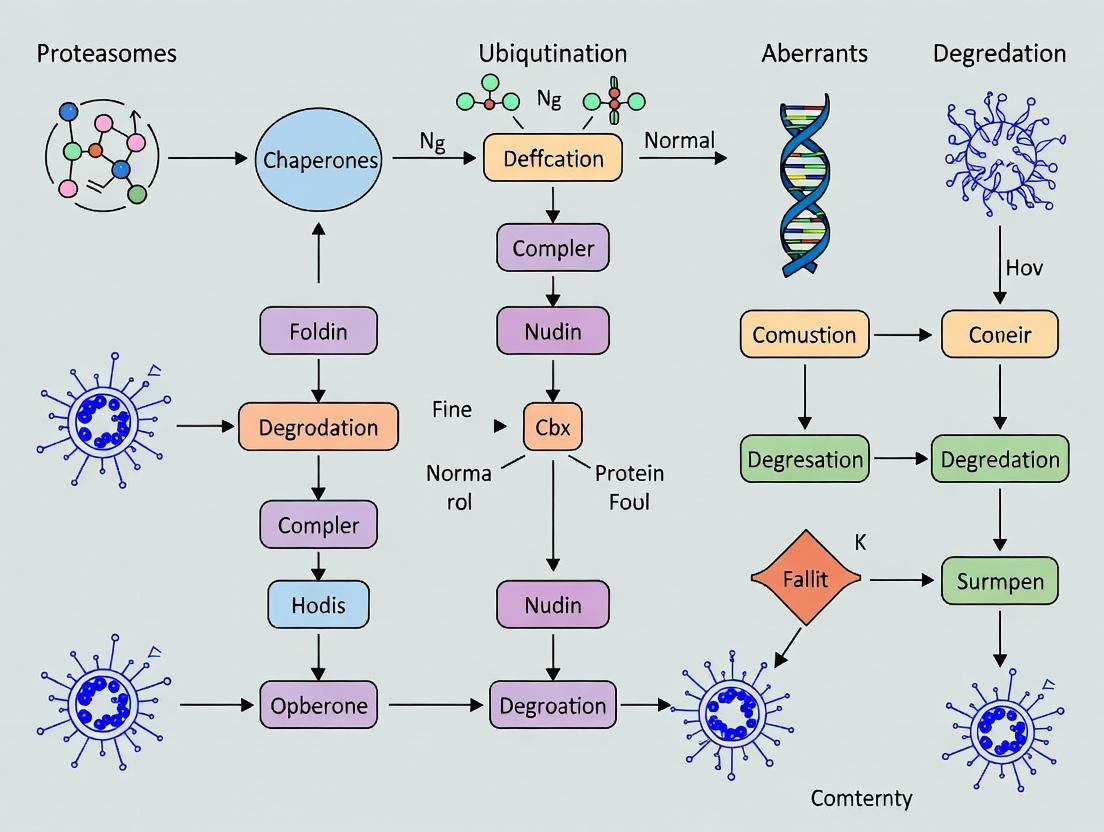

Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application in Proteolysis Studies | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Protease-Deficient Strains | In vivo host to minimize target protein loss. | E. coli BL21 Δlon ΔompT; E. coli JW0427 (ΔclpP Keio collection). |

| ATP Regeneration System | Sustains ATP levels for in vitro degradation assays. | Creatine Kinase + Phosphocreatine; Pyruvate Kinase + Phosphoenolpyruvate. |

| Non-hydrolyzable ATP Analogues | Negative control for ATP-dependence (blocks hydrolysis). | ATPγS, AMP-PNP. Note: binding may still occur. |

| Protease-Specific Inhibitors | Chemical validation of protease involvement. | ADEP1 (Activates ClpP); Nelfinavir (Inhibits ClpP); Phenanthroline (Zinc-chelator for FtsH). |

| SsrA-Degron Tagging System | Model substrate for ClpAP/XP or Lon in vitro/in vivo. | Plasmid encoding GFP-SsrA (AANDENYALAA). |

| Anti-ssrA Antibody | Detect degradation intermediates or SsrA-tagged proteins. | Commercial monoclonal available. |

| ATP Depletion Cocktail | Test ATP-dependence in vivo. | Sodium Azide + 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose. |

| Comprehensive Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (without EDTA) | General stabilization during cell lysis. | E.g., PMSF (serine), Bestatin (aminopeptidases), Pepstatin A (aspartic). |

| Comprehensive Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (with EDTA) | Inhibits metalloproteases (e.g., FtsH, OmpT) and ATP-dependent proteases requiring Mg2+. | Contains EDTA. Use based on target and buffer conditions. |

| Crosslinkers (e.g., Formaldehyde, BS3) | Capture transient protease-substrate complexes for pull-downs. | Critical for studying recognition before degradation. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Protein Degradation in Bacterial Hosts

This support center is designed within the context of a thesis on Addressing protein degradation in bacterial hosts research. It provides targeted guidance for common experimental challenges related to the major ATP-dependent cytoplasmic (Lon, Clp) and membrane-associated (FtsH, Outer Membrane Proteases) degradation systems in bacteria.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My recombinant protein expression yield in E. coli is unexpectedly low. Could it be targeted by host proteases? How can I identify the responsible pathway? A: Yes, cytoplasmic proteases like Lon and ClpAP/XP are common culprits. To diagnose:

- Co-express protease inhibitors: Co-express phage-encoded inhibitors (e.g., T4 PinA for Lon, T7 Ocr for ClpXP) in a test expression. A yield increase points to that protease.

- Use protease-deficient strains: Express your protein in a panel of isogenic strains (e.g., JW0427 (Δlon), JW0428 (ΔclpP), JW3691 (ΔftsH)). Compare yields. See Table 1 for strain data.

- Pulse-chase analysis: Perform a radioactive pulse-chase experiment to directly measure your protein's half-life in different genetic backgrounds.

Q2: My membrane protein is unstable during purification. Which degradation systems should I investigate? A: For inner membrane proteins, investigate FtsH. For outer membrane proteins or periplasmic domains, investigate the outer membrane protease systems (e.g., DegP, OmpT). Strategies include:

- Use an ftsH Ts (temperature-sensitive) strain at non-permissive temperature.

- Use strains lacking degP or ompT. For β-barrel assembly monitoring (BAM) complex-associated degradation, consider bamB or bamE mutants.

- Include specific protease inhibitors in lysis buffers: PMSF (serine proteases like DegP), EDTA (metalloproteases like FtsH), or hexidine (OmpT inhibitor).

Q3: How can I experimentally validate a direct substrate for the ClpAP or ClpXP protease? A: Validation requires in vitro reconstitution.

- Purify the Clp protease components (ClpA/P or ClpX/P) and your substrate protein.

- Perform an ATP-dependent degradation assay. Monitor substrate loss over time via SDS-PAGE or fluorescence (if substrate is tagged).

- Include essential controls: no ATP, ATPγS (non-hydrolyzable ATP), or a variant ClpP that cannot associate with the chaperone (e.g., ClpP-N151A).

Q4: My research focuses on inhibiting bacterial proteases for antibiotic development. What are the key recent findings on these proteases' essentiality? A: Recent genetic knockout studies show varying essentiality across species, informing drug target viability. See Table 2.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Yield of a Putative Lon Substrate.

- Step 1: Express protein in BL21(DE3) Δlon strain (e.g., JW0427). If yield improves, Lon is involved.

- Step 2: To confirm, perform an in vitro degradation assay with purified Lon protease (Protocol 1).

- Step 3: If degradation is observed, consider N-terminal engineering. Lon recognizes specific hydrophobic N-degrons. Adding an N-terminal Met or Ala, or using an N-terminal fusion tag (e.g., His-SUMO), can stabilize the protein.

Issue: Accumulation of Misfolded Proteins in the Periplasm Triggering DegP.

- Symptom: Cell lysis or growth defect upon induction of a periplasmic-targeted protein.

- Solution 1: Lower expression temperature (25-30°C) and inducer concentration.

- Solution 2: Co-express chaperones (e.g., Skp, SurA) to aid folding.

- Solution 3: Use a degP null strain, but be cautious as this strain is highly temperature-sensitive and may lyse at 37°C.

Issue: Difficulty in Measuring Real-time Degradation Kinetics.

- Solution: Implement a fluorescence-based degradation assay (Protocol 2). Tag your substrate with a fast-folding fluorescent protein (e.g., superfolder GFP). Purify the substrate and protease. Monitor fluorescence loss (due to degradation) in a plate reader in real-time. This provides precise kinetic parameters (k_deg).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro ATP-Dependent Degradation Assay for Lon Protease. Objective: To test if a purified protein is a direct substrate of the Lon protease. Reagents: Purified Lon protease (active hexamer), purified target protein, ATP, Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), MgCl₂, DTT. Method:

- Prepare a 50 µL reaction mix: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM MgCl₂, 5 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP.

- Add 1 µM Lon protease and 5 µM target substrate.

- Incubate at 30°C (or relevant physiological temperature).

- At time points (0, 5, 15, 30, 60 min), remove 10 µL aliquots and quench with 5 µL 3x SDS loading buffer.

- Boil samples for 5 min, run SDS-PAGE, and stain with Coomassie Blue.

- Controls: Omit ATP or use ATPγS. Omit Lon protease.

Protocol 2: Real-time Fluorescent Degradation Assay for ClpXP. Objective: To measure the kinetic rate of ClpXP-mediated degradation. Reagents: Purified ClpX hexamer, ClpP14 tetradecamer, sfGFP-tagged substrate, ATP-regeneration system (ATP, creatine phosphate, creatine kinase), HEPES-KOH buffer. Method:

- In a black 96-well plate, mix: 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl₂, 5 mM ATP, 10 mM creatine phosphate, 0.1 mg/mL creatine kinase.

- Add 100 nM ClpX, 200 nM ClpP, and 500 nM sfGFP-substrate.

- Immediately place plate in a pre-warmed (30°C) fluorescence plate reader.

- Monitor sfGFP fluorescence (Ex: 485 nm, Em: 510 nm) every 30 seconds for 60 minutes.

- Fit fluorescence decay curve to an exponential decay model to determine degradation rate constant.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common E. coli Protease-Deficient Strains for Troubleshooting

| Strain Genotype | Key Protease Deficiency | Primary Role | Common Application | Keio Collection ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δlon | Lon protease | Cytoplasmic quality control, SOS response | Stabilizing recombinant proteins | JW0427 |

| ΔclpP | ClpP peptidase | Core of ClpAP/XP complexes | Identifying ClpAP/XP substrates | JW0428 |

| ΔclpA | ClpA unfoldase | Part of ClpAP protease | Distinguishing ClpAP from ClpXP | JW3360 |

| ΔclpX | ClpX unfoldase | Part of ClpXP protease, disaggregation | Distinguishing ClpXP from ClpAP | JW0425 |

| ΔftsH | FtsH protease | Membrane quality control, σ32 regulation | Studying membrane protein stability | JW3691 |

| ΔdegP (ΔhtrA) | DegP protease | Periplasmic chaperone/protease | Expressing misfolding-prone periplasmic proteins | JW0159 |

| ΔompT | OmpT protease | Outer membrane protease | Preventing cleavage between Arg-Arg motifs | JW0367 |

Table 2: Essentiality of Major Bacterial Proteases as Potential Drug Targets

| Protease System | E. coli (Model Gram-negative) | B. subtilis (Model Gram-positive) | S. aureus (Pathogen) | M. tuberculosis (Pathogen) | Implication for Targeting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lon | Non-essential | Essential for sporulation | Essential | Essential | High-value target in pathogens. |

| ClpP | Non-essential | Essential | Essential | Essential | Broad-spectrum antibacterial target. |

| ClpX | Non-essential | Essential | Essential | Essential | Target paired with ClpP. |

| ClpA/C | Non-essential | Non-essential (ClpC) | Non-essential (ClpC) | Essential (ClpC1) | Species-specific targeting possible. |

| FtsH | Essential | Essential | Essential (FtsH/YdiC) | Essential (FtsH1) | Excellent but challenging target. |

| DegP | Non-essential (37°C) | Non-essential (HtrA-like) | Partially essential (HtrA1) | Non-essential (HtrA-like) | Likely a secondary target. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Degradation Research | Example Product/Catalog # |

|---|---|---|

| Protease-Deficient Strains | In vivo identification of protease involvement. | Keio Collection, CGSC E. coli strains. |

| Purified Protease Complexes | For in vitro validation of substrate degradation. | Enzo Life Sciences (Lon, ClpP), homemade purification. |

| ATPγS (Adenosine 5′-O-[γ-thio]triphosphate) | Non-hydrolyzable ATP analog; negative control for ATP-dependent proteases. | Sigma-Aldrich, Jena Bioscience. |

| Hexidine Dihydrochloride | Specific, potent inhibitor of outer membrane protease OmpT. | Tocris Bioscience, MilliporeSigma. |

| Casein, Fluorescein-Conjugated | Universal fluorogenic substrate for measuring general protease activity. | Thermo Fisher Scientific. |

| AAA+ Protease Activity Assay Kit | Colorimetric kit to measure ATPase activity linked to protease function. | Novus Biologicals, MyBioSource. |

| ssrA-Degron Tagging Vectors | Plasmid systems to add the 11-amino acid ClpXP/Lon recognition tag (AANDENYALAA) to any protein of interest. | Addgene plasmids #65192, #65193. |

| T7 PinA Expression Plasmid | Plasmid for inducible expression of T4 phage PinA protein, a specific inhibitor of Lon protease. | Addgene plasmid #159060. |

Diagrams

Diagram 1: Cytoplasmic Protein Degradation Pathways in E. coli

Diagram 2: Membrane & Periplasmic Protein Quality Control

Diagram 3: Experimental Workflow for Identifying a Protease

Technical Support Center

Welcome to the Protein Homeostasis Troubleshooting Hub. This resource is designed to support researchers in the field of Addressing protein degradation in bacterial hosts, focusing on experimental challenges related to cellular stress, protein misfolding, and quality control systems.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My recombinant protein in E. coli forms insoluble aggregates (inclusion bodies) even at low expression levels. What cellular triggers should I investigate? A: This indicates activation of stress responses and failure of quality control. Key checkpoints:

- Heat Shock Response (HSR) Saturation: Overexpression overwhelms chaperone systems (DnaK/DnaJ-GrpE, GroEL/ES). Monitor rpoH (σ³²) levels.

- Envelope Stress Response Activation: Misfolded proteins in periplasm trigger Cpx or σᴱ pathways. Check for periplasmic targeting signals.

- Proteolytic Overload: The ATP-dependent proteases (Lon, ClpXP, FtsH) may be insufficient. Consider co-expressing protease components or using mutant strains (e.g., Δlon).

- Experimental Protocol - Diagnostic: Perform fractionation (soluble vs. insoluble) and western blot for chaperones (DnaK, GroEL) and stress sigma factors (σ³², σᴱ) 30-60 minutes post-induction. Compare to empty vector control.

Q2: How can I quantitatively measure the activation level of the unfolded protein response (UPR) in my bacterial host system? A: Use reporter gene assays or quantitative PCR (qPCR) for key regulon genes.

- Protocol - qPCR for Cytoplasmic Stress:

- Extract total RNA from cultures at OD₆₀₀ ~0.6 pre- and post-induction (30, 60 min).

- Synthesize cDNA.

- Perform qPCR using primers for rpoH (σ³²), dnaK, groEL, and ibpA (small heat shock protein). Use rpoD (housekeeping sigma factor) as reference.

- Calculate fold-change (2^-ΔΔCT) relative to uninduced control. A >5-fold increase indicates significant HSR activation.

Q3: I suspect my target protein is being degraded by specific proteases. How can I identify which quality control protease is responsible? A: Employ a systematic knockout strain panel and pulse-chase analysis.

- Protocol - Pulse-Chase with Protease Knockouts:

- Transform your expression plasmid into isogenic E. coli strains: BW25113 (WT), JW0427 (Δlon), JW0428 (ΔclpP), JW0742 (ΔftsH).

- Grow cultures in minimal M9 medium to mid-log phase.

- Induce expression, then immediately add ³⁵S-Methionine for 2 minutes ("pulse").

- Chase with excess unlabeled methionine. Take samples at 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 min.

- Immunoprecipitate your protein, run SDS-PAGE, expose to phosphorimager.

- Quantify band intensity. Stabilization in a specific knockout strain identifies the responsible protease.

Q4: What are the recommended experimental conditions to minimize misfolding and promote soluble expression? A: Modulate cellular triggers by adjusting growth and induction parameters.

- Lower Growth Temperature: Shift to 25-30°C post-induction to slow translation and favor folding.

- Reduce Inducer Concentration: Use sub-saturating IPTG (e.g., 0.1 mM vs 1 mM) to lower expression rate.

- Use Rich Medium with Additives: Supplement TB or 2xYT medium with 1% glucose (represses leaky expression) and 5 mM betaine or sorbitol (chemical chaperones).

- Co-express Chaperones: Use plasmids expressing GroEL/ES or DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE sets. Induce chaperones 1 hour before target protein induction.

Table 1: Common Bacterial Stress Responses & Their Diagnostic Markers

| Stress Pathway | Primary Sensor/Trigger | Key Regulator | Major Effector Genes | Typical Fold-Increase* (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoplasmic Heat Shock | Misfolded cytoplasmic proteins, heat | σ³² (RpoH) | dnaK, groEL, ibpA/B | 10-50x |

| Periplasmic σᴱ Pathway | Misfolded OMPs in periplasm | σᴱ (RpoE) | rpoH, degP, skp | 5-30x |

| Cpx Envelope Stress | Misfolded pilin/adhesins | CpxA/R two-component | cpxP, degP, ppiA | 3-15x |

| Stringent Response | Amino acid starvation, ppGpp | (p)ppGpp | relA, spoT | Varies |

*Fold-increase is highly dependent on stressor severity. Values represent typical ranges observed under strong recombinant protein overexpression.

Table 2: Major ATP-Dependent Proteases in E. coli Quality Control

| Protease System | Cellular Location | Primary Substrate Type | Knockout Strain Viability | Common Phenotype in KO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lon (La) | Cytoplasm | Soluble misfolded proteins, specific regulators | Viable | Accumulation of SulA, RcsA; increased inclusion bodies? |

| ClpXP | Cytoplasm | Misfolded/aggregated proteins, SsrA-tagged peptides | Viable | Slower degradation of SsrA-tagged proteins |

| FtsH | Inner membrane | Misfolded membrane proteins, σ³² (RpoH) | Conditional | Temperature-sensitive growth; stabilized σ³² |

| ClpAP | Cytoplasm | Misfolded proteins, similar to ClpXP | Viable | Often redundant with ClpXP |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protein Degradation Research |

|---|---|

| BW25113 & Keio Collection Knockout Strains | Isogenic E. coli strains with single-gene deletions of proteases (lon, clpP, ftsH etc.) for determining degradation pathways. |

| *SsrA Degradation Tag (AAV) | An 11-amino acid tag added to stalled polypeptides by the tmRNA system. Fusion to target protein directs it to ClpXP and other proteases for study. |

| MG-262 (Lon Inhibitor) | A cell-permeable peptide aldehyde that selectively inhibits Lon protease activity in vivo and in vitro. |

| Cycloheximide | A eukaryotic translation inhibitor. In bacteria, used at high concentrations (1 mg/mL) in "chase" experiments to halt new synthesis after pulse labeling. |

| Anti-σ³² (RpoH) Antibody | For monitoring Heat Shock Response activation via western blot, correlating stress level with protein solubility. |

| pGro7/Tet Chaperone Plasmid | Plasmid expressing GroEL/ES chaperonins from a tetracycline-inducible promoter. Essential for testing chaperone-assisted folding. |

| Ni-NTA Magnetic Beads | For rapid purification of His-tagged proteins from small-scale cultures for solubility analysis, minimizing post-lysis degradation. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (for bacterial lysates) | Typically contains AEBSF (serine protease inhibitor), Bestatin (aminopeptidase inhibitor), E-64 (cysteine protease inhibitor) to halt degradation during cell lysis. |

*Sequence: AANDENYALAA

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Cellular Protein Quality Control Decision Pathway

Bacterial Stress Response Signaling Pathways

Protocol: Identifying Responsible Protease via Pulse-Chase

The N-End Rule and C-Terminal Degradation Signals in Bacteria

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My protein of interest is being degraded in my E. coli expression system despite using a protease-deficient strain. What could be the cause?

Answer: Protease-deficient strains (e.g., lon-/ompT-) only remove specific, common cytoplasmic proteases. The N-end rule and C-terminal degradation signals are pathways dependent on the ClpAP/ClpXP, ClpYQ (HsIUV), and FtsH proteases, which are still active in these strains. Degradation is likely due to an inherent N-degron (e.g., an N-terminal Met followed by a basic or bulky hydrophobic residue) or a C-terminal degron (e.g., a non-polar tail) in your protein. To stabilize, consider adding a stabilizing N-terminal residue (like Met-Ala-Ser) or a C-terminal fusion tag (like a ssrA-derived tag with mutations that avoid recognition).

FAQ 2: How can I experimentally determine if degradation is mediated by the N-end rule versus a C-terminal signal?

Answer: Perform a systematic truncation and tagging experiment.

- Construct a series of plasmids: Create C-terminal fusions of your protein to well-characterized degrons (e.g., the ssrA tag [AANDENYALAA] for ClpXP, or the LAA tag variant for inactivity) and to stabilizing sequences (e.g., the ssrA-DAS tag, which avoids recognition).

- Create N-terminal variants: Use mutagenesis to alter the second residue (after the initiator Met) to a stabilizing (e.g., Ala, Ser) versus destabilizing (e.g., Arg, Phe, Leu) residue.

- Pulse-chase analysis: Express these variants in your bacterial host and perform a pulse-chase experiment, followed by immunoprecipitation and SDS-PAGE.

- Analyze degradation kinetics: Compare half-lives. If degradation is abolished by an N-terminal Ala but not by a C-terminal stabilizer, it's likely N-end rule mediated, and vice-versa.

FAQ 3: What are the key controls for a pulse-chase experiment measuring protein half-life in bacteria?

Answer:

- Negative Control: Express a known stable protein (e.g., a folded, native bacterial protein) under the same promoter.

- Positive Control: Express a protein with a known strong degron (e.g., X-beta-galactosidase with an N-terminal Arg or a protein fused to the native ssrA tag).

- Pharmacological Control: Treat cells with a protonophore (e.g., CCCP) to deplete ATP. ATP depletion should inhibit ClpAP/XP and FtsH protease activity, stabilizing the protein and confirming ATP-dependent proteolysis.

- Time Zero Point: Always include a sample harvested immediately after the pulse ("0 min" chase) to establish the starting amount of protein.

FAQ 4: My protein half-life data is highly variable between replicates. What are common sources of error?

Answer:

| Source of Error | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Cell Density | Variable incorporation of radioactive label. | Always induce expression at the exact same OD600. Use a high-precision spectrophotometer. |

| Chase Inefficiency | Residual label incorporation continues. | Increase chase solution concentration (use at least 0.5% final w/v of unlabeled methionine/cysteine). Ensure thorough mixing. |

| Sample Processing Delay | Degradation continues during harvest. | Use pre-chilled tubes and centrifuge. Process samples on ice. Add protease inhibitor cocktails to lysis buffer (though they may not inhibit ATP-dependent proteases fully). |

| Immunoprecipitation Efficiency | Variable protein recovery. | Pre-clear lysate with control beads. Use excess, validated antibody. Ensure consistent bead washing across samples. |

Experimental Protocol: Pulse-Chase Analysis for Protein Half-Life Determination

Objective: To measure the in vivo half-life of a protein in E. coli.

Materials:

- Bacterial strain expressing protein of interest.

- M9 minimal medium.

- Required antibiotics.

- IPTG for induction.

- [³⁵S]-Methionine/Cysteine mixture.

- 1M unlabeled L-methionine and L-cysteine (chase solution).

| Key Research Reagent Solutions | Function |

|---|---|

| M9 Minimal Medium | Supports bacterial growth while enabling efficient labeling with radioactive amino acids. |

| [³⁵S]-Methionine/Cysteine | Radioactive tracer incorporated into newly synthesized proteins during the "pulse." |

| 1M Unlabeled Methionine (Chase) | Floods the intracellular pool, stopping further incorporation of the radioactive label. |

| IPTG | Inducer for T7/lac-based expression systems. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (EDTA-free) | Inhibits serine, cysteine, and metalloproteases during cell lysis and sample processing. |

| Specific Antibody for Protein of Interest | For immunoprecipitation of the target protein from total lysate. |

| Protein A/G Beads | Immobilized beads to capture antibody-protein complexes. |

Procedure:

- Grow Cells: Inoculate 5 mL of M9 minimal medium (+ antibiotics) with a fresh colony. Grow overnight at 37°C.

- Subculture: Dilute the overnight culture 1:50 into 2 mL of fresh, pre-warmed M9 medium. Grow at 37°C with shaking to mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.5).

- Induce: Add IPTG to the required concentration. Induce for 15 minutes.

- Pulse Labeling: Add 20-40 µCi of [³⁵S]-Met/Cys mix. Incubate for 1 minute at 37°C.

- Chase: Add 100 µL of 1M unlabeled methionine and cysteine (1:1 mix). Immediately take the "0 min" chase sample (200 µL) and transfer to a tube on ice containing 10 µL of 1% sodium azide.

- Time Points: Take 200 µL samples at defined time points (e.g., 2, 5, 15, 30, 60 min) post-chase, and quench in azide on ice.

- Harvest: Pellet cells (13,000 rpm, 1 min, 4°C). Wash once with ice-cold PBS. Flash-freeze pellets.

- Lysis & Immunoprecipitation: Thaw pellets in lysis buffer with inhibitors. Sonicate briefly. Clarify lysate by centrifugation. Incubate supernatant with specific antibody (1 hr, 4°C), then add Protein A/G beads (1 hr, 4°C). Wash beads thoroughly.

- Analysis: Elute protein in SDS loading buffer. Separate by SDS-PAGE. Dry gel and expose to a phosphorimager screen. Quantify band intensity.

- Calculation: Plot log(% remaining signal) vs. time. The half-life is derived from the slope of the linear fit.

Table 1: Representative Protein Half-Lives Mediated by N-Degrons in E. coli

| N-Terminal Residue (after Met cleavage) | Recognized by | Example Protein | Approximate Half-life (minutes) | Reference Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arg (Type I) | ClpAP (via ClpS adapter) | X-beta-gal (N-Arg) | < 5 | J. Biol. Chem. 1996 |

| Leu (Type II) | ClpAP (via ClpS) | X-beta-gal (N-Leu) | ~10 | J. Biol. Chem. 1996 |

| Asp (Nt-Asp/Nt-Glu) | L, D-specific NTAQ | Model Substrate (Smt3-DHFR) | ~30 | Nature 2009 |

| Ala (Stabilizing) | N/A | X-beta-gal (N-Ala) | > 180 (stable) | J. Biol. Chem. 1996 |

Table 2: Common C-Terminal Degrons and Their Recognition in Bacteria

| C-Terminal Signal | Sequence Motif (Example) | Recognized by Protease | Primary Function | Effect on Half-life* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ssrA Tag (Wild-type) | AANDENYALAA | ClpXP, ClpAP, FtsH, ClpYQ | Trans-translation rescue | < 10 min |

| ssrA-DAS Tag | AANDENYALDAS | None (blocked) | Experimental stabilization | > 180 min |

| ssrA-AAV Tag | AANDENYAAAV | ClpXP (specific) | Specific ClpXP targeting | < 20 min |

| Non-polar Tail (Rule 1) | -LL, -IL, -VL | FtsH (membrane-bound) | Membrane protein quality control | Variable |

| PDZ-Binding Motif | -DSWV | Tsp (Prc) | Periplasmic/C-terminal sensing | ~30 min |

*Half-lives are approximate and depend on protein context and growth conditions.

Signaling Pathway & Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: The Bacterial N-End Rule Pathway

Diagram 2: C-Terminal Degron Recognition by Bacterial Proteases

Diagram 3: Pulse-Chase Experiment Workflow

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for Bacterial Protein Degradation Research

Framing Context: This support center is designed to assist researchers within the broader thesis of Addressing protein degradation in bacterial hosts for recombinant protein production and metabolic engineering. It addresses practical experimental challenges encountered when studying novel proteases and their regulation.

FAQ & Troubleshooting Section

Q1: My recombinant protein yield in E. coli is unexpectedly low, and I suspect degradation by a novel ATP-independent protease. How can I confirm this and identify the culprit? A: This is a common issue. Post-2020 research has highlighted the role of novel ATP-independent proteases like C-terminal tail-specific proteases.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Perform a Cycloheximide Chase Analysis: Treat cultures with cycloheximide to halt translation and monitor protein decay over time via immunoblotting. Compare degradation rates in wild-type vs. protease knockout strains.

- Conduct a In Vitro Degradation Assay: Purify your target protein and incubate it with bacterial cell lysate. Use protease class inhibitors (e.g., PMSF for serine proteases, EDTA for metalloproteases) to narrow down the protease family.

- Utilize a Global Proteomics Approach: Perform Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) proteomics on samples from cells expressing your protein vs. controls. Look for upregulated endogenous proteases and downregulated substrate proteins.

Key Protocol: Cycloheximide Chase Assay

- Materials: Log-phase bacterial culture, cycloheximide (100 µg/mL final concentration), SDS-PAGE/Western blot setup.

- Method:

- Induce your target protein expression.

- Add cycloheximide to arrest translation.

- Collect aliquots at T=0, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes post-addition.

- Immediately lyse cells, run SDS-PAGE, and perform immunoblotting for your target.

- Quantify band intensity and plot degradation kinetics.

Q2: I am studying a putative new regulator of the ClpXP protease. How can I validate its interaction and functional impact? A: Recent studies emphasize allosteric and adaptor-mediated regulation of ClpXP.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check for Direct Interaction: Use Bacterial Adenylate Cyclase Two-Hybrid (BACTH) assay or Co-purification/Pull-down with tagged regulator and ClpX/P components.

- Assess Functional Consequence: Measure degradation kinetics of a known ClpXP substrate (e.g., SsrA-tagged GFP) in vivo in strains overexpressing or lacking your regulator. Use the in vitro degradation assay with purified components.

- Determine Regulatory Mechanism: Test if the regulator affects ClpXP ATPase activity (using a commercial ATPase assay kit) or substrate unfolding.

Key Protocol: In Vitro ClpXP Degradation Assay with a Novel Regulator

- Materials: Purified ClpX, ClpP, SsrA-tagged fluorescent substrate (e.g., GFP-SsrA), ATP regeneration system (ATP, Creatine Phosphate, Creatine Kinase), purified putative regulator.

- Method:

- In a reaction buffer, mix ClpX (1 µM), ClpP (3 µM), substrate (5 µM), and ATP regeneration system.

- Set up parallel reactions: one with regulator protein (2-5 µM), one without.

- Incubate at 30-37°C.

- Monitor fluorescence loss (ex/em 488/510 nm for GFP) over 60-90 minutes to measure degradation rate.

- Calculate rate constants for comparison.

Q3: My protease activity assays are showing high background noise. What controls are critical for post-2020 methodologies? A: High background often stems from inadequate controls for ATP-dependent proteolysis or non-specific cleavage.

- Essential Controls Table:

Control Condition Purpose Expected Outcome for Valid Assay No Protease (Substrate only) Measures substrate stability & background signal. Minimal signal change. Protease + Broad-Spectrum Inhibitor (e.g., PMSF, EDTA) Confirms activity is protease-mediated. Significant reduction in activity. ATP-depleted System (Apyrase or non-hydrolyzable ATPγS) For ATP-dependent proteases (Clp, Lon, FtsH). Abolished activity confirms ATP dependence. Catalytic Mutant Protease Gold standard for specificity. Activity matching "no protease" control. Unlabeled Competitor Substrate Tests specificity of degradation signal. Reduced degradation of primary substrate.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| SsrA-Degron Tagged GFP (e.g., GFP-ssrA) | Universal, real-time reporter substrate for AAA+ proteases (ClpXP, ClpAP). | Fluorescent signal loss directly correlates with degradation. |

| Protease-Targeted Degrader (PROTAC) Molecules | Bifunctional molecules to induce targeted protein degradation in bacterial systems. | Used to study synthetic regulation and potential antimicrobial strategies. |

| Phusion or Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | For precise knockout/knock-in of protease genes via CRISPR/Cas9 or lambda Red. | Essential for creating clean genetic backgrounds. |

| HaloTag or SNAP-tag Substrates | Label proteins for pulse-chase imaging or pull-downs to study degradation dynamics. | Provides versatile, covalent labeling. |

| TMTpro 16plex or iTRAQ Reagents | For multiplexed quantitative proteomics to identify protease substrates and global effects. | Enables high-throughput substrate discovery. |

| Membrane-Permeant Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) | To inhibit ATP-dependent proteases in vivo for validation experiments. | Note: Specificity for bacterial proteases must be verified. |

| anti-Phospho Antibody Panels | To investigate post-translational regulatory mechanisms (e.g., phosphorylation) of novel proteases. | Key for studying regulatory signaling. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Post-2020 Bacterial Protease Regulation Network

Diagram 2: Workflow for Novel Protease Characterization

Table 1: Key Novel Proteases & Regulators Identified (Post-2020)

| Protease/Regulator Name | Host Bacterium | Key Function | Impact on Heterologous Protein Yield (When Deleted) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CtpA-like Protease | Bacillus subtilis | C-terminal processing, quality control | Up to 2.3-fold increase for secreted proteins | 2022 |

| Novel Adaptor "ZipR" | Escherichia coli | Regulates ClpXP specificity | Modulates degradation of specific substrates by ~70% | 2021 |

| Lon2 Isoform | Pseudomonas putida | Stress-induced, degrades misfolded proteins | 1.8-fold increase in certain enzyme activities | 2023 |

| PepZ (Metalloprotease) | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Unknown physiological role, degrades recombinant proteins | Yield improvement of 50-150% for various targets | 2022 |

Table 2: Efficacy of Common Degradation-Tag Systems in E. coli

| Degradation Tag | Targeted Protease | Baseline Half-life (min)* | Half-life in Protease Knockout (min)* | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SsrA (AAV) | ClpXP, ClpAP | ~5-10 | >120 | Fast-turnover studies, real-time assays |

| YbaQ Tag | ClpYQ (HsUV) | ~25-40 | >180 | Medium-turnover, alternative to SsrA |

| LAA (C-terminal) | Unknown ATP-independent | ~45-70 | ~45-70 (No change) | For exploring novel proteolytic pathways |

| T7 Tag | Largely stable | >240 | >240 | Control for non-specific degradation |

*Representative half-life ranges under standard laboratory conditions. Actual values depend on protein context.

Combatting Degradation: Proven Strategies and Cutting-Edge Tools for Stabilization

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My target protein yield is still low in BL21(DE3) Δlon ΔompT. What are other common proteases or degradation pathways to consider?

- Answer: While Δlon (cytosolic protease) and ΔompT (outer membrane protease) are common deletions, residual degradation can occur. Key considerations include:

- Cytoplasmic Proteases: clpP, clpA, clpX, hsIVU, ftsH.

- Periplasmic Proteases: degP, ptrA.

- Cellular Stress: Protein expression itself can induce stress responses, upregulating other proteases. Consider tuning expression (lower temperature, lower inducer concentration) or using strains with additional deletions (e.g., ΔhtpR which affects heat shock response).

- N-terminal Degradation: Ensure your expression construct does not encode an unfavorable N-degron. Use N-terminal tags (e.g., His-SUMO) to mask destabilizing residues.

FAQ 2: How do I choose between BL21(DE3) Δlon, BL21(DE3) ΔompT, and the double mutant BL21(DE3) Δlon ΔompT?

- Answer: The choice depends on the protein's localization and susceptibility.

| Strain Genotype | Primary Protease Target | Recommended Application | Key Advantage | Potential Drawback |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL21(DE3) Δlon | Cytosolic ATP-dependent protease Lon | Cytosolic expression of proteins prone to aggregation or misfolding. | Reduces degradation of misfolded cytoplasmic proteins. | Does not protect against periplasmic or membrane-associated degradation. |

| BL21(DE3) ΔompT | Outer membrane protease OmpT | Proteins secreted to the periplasm or undergoing cell fractionation. | Prevents cleavage during cell lysis and periplasmic preparation. | No protection against cytoplasmic degradation. |

| BL21(DE3) Δlon ΔompT | Both Lon and OmpT | General purpose for difficult-to-express proteins; proteins where localization is ambiguous. | Comprehensive protection against two major degradation pathways. | Slightly slower growth rate than wild-type; other proteases remain active. |

FAQ 3: I observe protein degradation even in the Δlon ΔompT strain. What is a detailed protocol to confirm and identify the protease responsible?

- Answer: Follow this systematic protocol to investigate protease involvement.

Experimental Protocol: Protease Inhibition & Identification Assay

Objective: To confirm protease-mediated degradation and identify the protease class responsible. Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table. Method:

- Culture & Expression: Transform your target plasmid into BL21(DE3) Δlon ΔompT. Grow overnight culture in LB+antibiotic. Dilute 1:100 in fresh medium (50 mL). Grow at 37°C to OD600 ~0.6.

- Induction & Inhibition: Induce with optimal concentration of IPTG. Immediately split culture into 4 x 12.5 mL aliquots in separate flasks.

- Treatment Conditions:

- Flask A (Control): Add no inhibitor.

- Flask B (Serine/Cysteine Inhibitor): Add PMSF to 1 mM.

- Flask C (Metalloprotease Inhibitor): Add EDTA to 10 mM.

- Flask D (ATP-depletion for ATP-dependent proteases): Add Sodium Azide to 20 mM.

- Harvesting: Express protein at appropriate temperature for 3-4 hours. Take 1 mL samples pre-induction and at 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours post-induction. Pellet cells immediately at 4°C.

- Analysis: Resuspend pellets in SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Analyze by SDS-PAGE and Western Blot. Compare band intensity and degradation pattern across conditions.

FAQ 4: What is the signaling pathway that leads to stress-induced protease upregulation in E. coli, and how do deletions like Δlon affect it?

- Answer: The primary pathway for cytoplasmic unfolded protein response involves the heat shock sigma factor σ^32 (RpoH).

Diagram Title: σ32-Mediated Stress Response & Δlon Impact

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example/Catalog Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| BL21(DE3) Δlon ΔompT Cells | Primary protease-deficient host strain for recombinant expression. | Commercial glycerol stocks from major vendors (e.g., NEB C3030, Novagen 70837). |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Serine/Cysteine) | Broad-spectrum inhibition of serine and cysteine proteases in lysates. | Ready-to-use tablets or EDTA-free liquid formulations for purification. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Chelates metal ions, inhibiting metalloprotease activity. | Prepare 0.5M stock, pH 8.0. Use in lysis buffers at 1-10 mM. |

| PMSF (Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) | Irreversible serine protease inhibitor. Note: Short half-life in aqueous solution. | Add fresh from 100-200 mM stock in ethanol or isopropanol to lysis buffer. |

| Protease Degradation Reporter Plasmid | Plasmid expressing a model unstable protein (e.g., SRP-GFP) to assay protease activity in vivo. | Used to validate strain protease backgrounds or screen for new mutants. |

| Affinity Purification Resin (Ni-NTA, GST) | For rapid purification of tagged target proteins before they are degraded. | Critical for capturing full-length protein from protease-deficient strains. |

| Tunable Expression Vector (pET, pBAD) | Vector allowing control of expression level (e.g., via IPTG or arabinose concentration). | Fine-tuning expression reduces misfolding and stress, complementing protease deletion. |

Within the broader thesis of Addressing Protein Degradation in Bacterial Hosts, fusion tags are critical tools for enhancing recombinant protein yield and solubility. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance for researchers employing common stabilizer tags: SUMO (Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier), TrxA (Thioredoxin), and MBP (Malose-Binding Protein). These tags mitigate aggregation and proteolytic degradation in E. coli and other expression systems.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is my fusion protein still insoluble despite using an MBP tag?

Answer: MBP enhances solubility but does not guarantee it. Insolubility can persist due to:

- Expression Conditions: Too rapid expression (high inducer concentration, prolonged induction) leads to aggregation.

- C-Terminal Fusion: MBP is most effective as an N-terminal tag. C-terminal fusions offer less stabilization.

- Intrinsically Disordered Regions: The target protein may contain regions prone to aggregation that overwhelm MBP's chaperone-like activity.

- Solution: Optimize induction (e.g., lower IPTG concentration, reduce temperature to 16-18°C post-induction). Consider testing a dual-tag system (e.g., MBP-SUMO-Target).

FAQ 2: My SUMO protease cleavage is inefficient. What are the common causes?

Answer: Incomplete cleavage by Ulp1 protease can occur due to:

- Inaccessible Cleavage Site: The recognition sequence (SUMO-ψ-x-T-h) must be exposed. Flanking sequences or tag folding can block access.

- Protease Inactivity: The Ulp1 protease stock may have degraded. Aliquot and store at -80°C.

- Suboptimal Reaction Conditions: Incorrect pH, temperature, or ionic strength. Always include a control SUMO-protein.

- Solution: Perform cleavage optimization with varied protease:substrate ratios (1:50 to 1:1000), extended time (2-16h at 4°C), and ensure the reaction buffer contains 1 mM DTT.

FAQ 3: After TrxA fusion purification, my target protein is degraded. How can I prevent this?

Answer: TrxA can reduce disulfide bonds in the target, potentially destabilizing it. Degradation suggests host protease activity.

- Protease Inhibition: Add a cocktail of EDTA-free protease inhibitors during lysis. Use bacterial strains deficient in cytoplasmic proteases (e.g., lon and ompT mutants).

- Altered Redox State: The reducing activity of TrxA might be disruptive. Consider using a redox-inactive TrxA mutant (C32S/C35S) as the fusion partner.

- Solution: Switch to a non-enzymatic stabilizer tag like MBP or SUMO, or employ a tighter, more rapid purification scheme.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Fusion Tags as Stabilizers

| Tag | Size (kDa) | Primary Mechanism | Typical Solubility Increase | Key Advantage | Common Elution Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUMO | ~11 | Acts as a folding chaperone; maintains target in soluble state. | 2- to 10-fold | Enhances expression & allows precise cleavage by Ulp1. | Imidazole (His-SUMO) or Ulp1 cleavage. |

| TrxA | ~12 | Reduces disulfide bonds; has intrinsic chaperone activity. | 5- to 20-fold | Highly soluble; can improve folding of disulfide-rich targets. | DTT or Thiol-based reduction. |

| MBP | ~40 | Strong chaperone-like activity; increases solubility of fused passenger. | Often >20-fold | Most effective solubility enhancer; aids in affinity purification. | Maltose (10-20 mM). |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Fusion Tag Issues

| Problem | SUMO-Related Check | TrxA-Related Check | MBP-Related Check |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Yield | Verify Ulp1 site integrity. Check for internal SUMO-like sequences in target. | Ensure reducing agent (DTT) in lysis buffer. | Confirm amylose resin activity with a positive control. |

| Cleavage Issues | Optimize Ulp1:substrate ratio & incubation time. | N/A (cleavage via enterokinase or factor Xa). | N/A (cleavage via specific protease site). |

| Aggregation | Express at lower temperature (16-25°C). | Co-express with chaperone plasmids (e.g., GroEL/ES). | Use lower inducer (IPTG) concentration (0.1-0.5 mM). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Stabilization Efficiency of Different Tags

Objective: Quantify the solubility enhancement provided by SUMO, TrxA, and MBP fusions.

- Clone the target gene into parallel expression vectors encoding N-terminal His₆-SUMO, His₆-TrxA, and His₆-MBP tags.

- Transform each construct into an appropriate E. coli expression strain (e.g., BL21(DE3)).

- Induce Expression in small-scale cultures (5 mL) with 0.5 mM IPTG at 18°C for 16-20 hours.

- Harvest & Lyse: Pellet cells, resuspend in lysis buffer, and lyse by sonication.

- Fractionate: Centrifuge at 15,000 x g for 30 min. Separate supernatant (soluble) from pellet (insoluble).

- Analyze: Run equal % of total, soluble, and insoluble fractions on SDS-PAGE. Quantify band intensity to calculate soluble yield %.

Protocol 2: Cleaving the SUMO Fusion Tag

Objective: Release the native target protein from the SUMO tag.

- Purify the His₆-SUMO-target protein via Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC).

- Dialysis: Dialyze the eluted protein into cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT).

- Cleavage Reaction: Add Ulp1 protease at a 1:100 (w/w) ratio to the fusion protein. Incubate at 4°C for 4-16 hours.

- Remove Tag: Pass the reaction mixture over a fresh Ni-NTA column. The cleaved target protein will flow through, while the His₆-SUMO tag and protease bind.

- Validate: Analyze flow-through and eluate by SDS-PAGE.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| pET SUMO / Champion Vectors | Commercial vectors for seamless cloning and expression of His-SUMO fusions. |

| Ulp1 Protease (SUMO Protease) | Highly specific protease for cleaving the SUMO tag from the fusion partner. |

| Amylose Resin | Affinity resin for purifying MBP-tagged fusion proteins via maltose binding. |

| Reduction-Optimized E. coli Strains (e.g., Origami) | Enhance disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm, useful for TrxA-fused targets. |

| Protease-Deficient Strains (e.g., BL21(DE3) lon ompT) | Minimize non-specific degradation of recombinant fusion proteins. |

| 3C/PreScission/TEV Protease | Alternative site-specific proteases for cleaving tags when the target has a native SUMO-like sequence. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Mechanism of Fusion Tag Stabilization Against Degradation

Title: How Fusion Tags Prevent Protein Degradation

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Tag Comparison

Title: Workflow to Compare Tag Stabilization Efficiency

Technical Support Center

This support center provides troubleshooting guidance for researchers aiming to optimize recombinant protein expression in bacterial hosts, specifically to minimize cellular stress and subsequent protein degradation, as part of a thesis on Addressing protein degradation in bacterial hosts.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My target protein is consistently degraded, showing multiple lower molecular weight bands on SDS-PAGE. I am using a standard protocol with IPTG induction at 37°C in LB media. What are my primary optimization targets?

A: Degradation often stems from host cell stress, leading to protease activation. Your primary targets are:

- Temperature: Reduce induction temperature to 18-30°C.

- Inducer Concentration: Lower IPTG concentration from typical 0.5-1 mM to 0.01-0.1 mM.

- Media: Switch to auto-induction media or enriched media (e.g., TB) to better support metabolic demand. This combinatorial approach slows protein synthesis, improves folding, and reduces metabolic burden.

Q2: How do I systematically test the combination of temperature, inducer concentration, and media?

A: Implement a Design of Experiment (DoE) approach. A recommended factorial screening experiment is outlined below.

Protocol: Factorial Screen for Expression Optimization

- Objective: Identify conditions minimizing stress and degradation.

- Host Strain: E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS (for tight repression and protease inhibition).

- Experimental Matrix: See Table 1.

- Procedure:

- Transform host with your expression plasmid. Pick single colonies into 5 mL primary culture (LB with appropriate antibiotic). Grow overnight at 37°C, 220 rpm.

- Inoculate 50 mL of each test media (in duplicate) to an OD600 of 0.1 from the overnight culture.

- Grow at the designated pre-induction temperature until OD600 ~0.6.

- Induce cultures with the specified IPTG concentration.

- Immediately shift flasks to the designated post-induction temperature.

- Harvest cells 16-20 hours post-induction for low temperatures (18-25°C) or 4 hours for 37°C.

- Lyse samples, analyze total protein via SDS-PAGE, and assess solubility via fractionation. Use Western blot for specific degradation detection.

- Key Analysis: Compare yield, solubility, and degradation band intensity across conditions.

Q3: What specific reagents and media components are critical for minimizing stress during expression?

A: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Stress Minimization |

|---|---|

| Auto-Induction Media (e.g., Overnight Express) | Uses lactose as a mild, self-regulating inducer; eliminates the metabolic shock of a bolus IPTG add. |

| Terrific Broth (TB) | High nutrient density supports growth and protein production without excessive cell density stress. |

| IPTG (Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside) | Lower concentrations (µM range) reduce translational burden and T7 RNA polymerase toxicity. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails (e.g., PMSF, EDTA-free cocktails) | Added immediately at cell lysis to inhibit endogenous proteases released during disruption. |

| Chaperone-Enriched Strains (e.g., Origami B, ArcticExpress) | Co-express chaperonins (GroEL/GroES) to assist in proper folding, reducing aggregation and targeting for degradation. |

| Glucose (for repressive media) | In E. coli, represses basal expression from T7/lac promoters pre-induction, minimizing stress before induction. |

Q4: The optimization pathways seem interconnected. Can you map the decision logic?

A: Yes. The following diagram outlines the primary decision pathway for condition optimization to mitigate stress responses.

Table 1: Example Factorial Experiment Matrix for Expression Optimization

| Condition | Media | Pre-Induction Temp. | Post-Induction Temp. | IPTG Concentration | Expected Impact on Stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Control) | LB | 37°C | 37°C | 1.0 mM | High (Baseline stress) |

| 2 | LB | 37°C | 25°C | 1.0 mM | Medium (Reduced heat shock) |

| 3 | LB | 37°C | 18°C | 1.0 mM | Low (Significant slowdown) |

| 4 | LB | 37°C | 25°C | 0.1 mM | Low (Combo: Low temp + low inducer) |

| 5 | TB | 37°C | 25°C | 0.1 mM | Very Low (Combo + rich media) |

| 6 | Auto-Induction | 37°C | 25°C | 0 mM (Lactose) | Very Low (Gradual induction) |

Q5: What is the detailed protocol for testing protein solubility and degradation under different conditions?

A: Protocol: Solubility Fractionation & Degradation Assessment

- Materials: Lysis Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mg/mL Lysozyme, 1x Protease Inhibitor), Benzonase, Centrifuge, SDS-PAGE reagents.

- Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend pelleted cells from 1 mL culture in 100 µL Lysis Buffer. Incubate on ice for 30 min. Sonicate on ice (3x 10 sec pulses). Add 1 µL Benzonase, incubate 15 min on ice.

- Insoluble Pellet Separation: Centrifuge at 15,000 x g for 20 min at 4°C. Carefully transfer supernatant (soluble fraction) to a new tube.

- Wash Pellet: Resuspend the pellet in 100 µL of Lysis Buffer (without lysozyme). Centrifuge again at 15,000 x g for 10 min. Discard supernatant.

- Solubilize Insoluble Fraction: Resuspend the final washed pellet in 100 µL of Lysis Buffer containing 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 or 8M Urea (insoluble/aggregate fraction).

- Analysis: Mix equal volumes (e.g., 20 µL) of the original total lysate (step 1, before centrifugation), soluble fraction, and insoluble fraction with SDS-PAGE loading dye. Boil for 10 min. Load equal percentages of total culture volume on SDS-PAGE. Perform Coomassie staining and/or Western blot.

- Interpretation: A strong target band in the soluble fraction indicates success. Smearing or lower bands in the total/soluble fractions indicate degradation. A strong band only in the insoluble fraction indicates aggregation.

Co-expression of Molecular Chaperones (GroEL/GroES, DnaK/J) to Prevent Misfolding

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Despite co-expressing GroEL/ES and DnaK/J, my target protein still shows low solubility and high degradation. What could be the issue? A: This is a common issue often related to expression kinetics. The chaperones may be expressed at different rates or times than your target protein. Ensure you are using compatible plasmids with inducible promoters (e.g., pGro7 for GroEL/ES and pKJE7 for DnaK/J in E. coli) and induce chaperone expression before inducing your target protein (typically 1-2 hours prior). Check plasmid compatibility and antibiotic selection. Monitor cell health via OD600; over-expression can cause toxicity. Titrate chaperone inducer concentrations (e.g., L-arabinose for pGro7, tetracycline for pKJE7) as excessive levels can burden the host.

Q2: What is the optimal temperature for co-expression to prevent misfolding? A: While lower temperatures (e.g., 25-30°C) generally favor solubility, the optimal balance between protein yield and folding varies. A typical protocol is to induce chaperone expression at 37°C, then reduce temperature to 25-30°C for target protein induction. See Table 1 for summarized data from recent studies.

Q3: How do I choose between GroEL/ES and DnaK/J systems for my protein? A: The choice can be empirical. GroEL/ES is primarily involved in folding post-translation for proteins in the 10-60 kDa range, while the DnaK/J (Hsp70/Hsp40) system acts during translation on emerging chains and on misfolded proteins. For large, multi-domain proteins (>50 kDa), DnaK/J may be more effective. For proteins prone to aggregation, combined co-expression is often best. Start with a factorial experiment (see Experimental Protocol 1).

Q4: My bacterial growth is severely inhibited when I induce the chaperone systems. How can I mitigate this? A: Chaperone over-expression is metabolically costly. Mitigation strategies include: 1) Use a lower-copy-number plasmid for chaperone expression. 2) Optimize inducer concentration (see Table 1). 3) Use richer media (e.g., Terrific Broth) to support metabolic demand. 4) Shorten the pre-induction time for chaperones to 30-60 minutes.

Q5: How can I quantitatively assess the improvement in soluble yield from chaperone co-expression? A: Perform a comparative solubility assay. Express your target with and without chaperones under optimized conditions. Lyse cells, separate soluble and insoluble fractions by centrifugation, and analyze by SDS-PAGE with densitometry. Use a His-tag on your target for quick purification and yield quantification via Bradford assay. Report data as "mg of soluble protein per liter of culture" (see Experimental Protocol 2).

Data Presentation

Table 1: Summary of Optimized Conditions for Chaperone Co-expression in E. coli

| Chaperone System | Typical Plasmid | Common Inducer | Optimal Pre-Induction Time | Typical Inducer Concentration Range | Target Protein Solubility Increase (Range Reported)* | Key Reference Strain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GroEL/GroES | pGro7, pG-KJE8 | L-arabinose | 1-2 hours | 0.1 - 1.0 mg/mL | 2 to 5-fold | BL21(DE3), K-12 deriv. |

| DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE | pKJE7, pG-KJE8 | Tetracycline | 30 mins - 1 hour | 10 - 100 ng/mL | 1.5 to 4-fold | BL21(DE3) |

| Combined Systems | pG-KJE8 | L-arabinose + Tetracycline | 1 hour (both) | 0.5 mg/mL + 50 ng/mL | 3 to 10-fold | BL21(DE3) |

*Increase is highly dependent on the specific target protein.

Experimental Protocols

Experimental Protocol 1: Initial Screening of Chaperone Systems

- Transformations: Co-transform your target protein expression plasmid (e.g., pET vector) individually with chaperone plasmids pGro7 (GroEL/ES), pKJE7 (DnaK/J/GrpE), pG-KJE8 (combined), and an empty vector control into your expression host (e.g., E. coli BL21(DE3)).

- Culture: Inoculate 5 mL cultures (appropriate antibiotics) and grow overnight at 37°C.

- Chaperone Pre-induction: Dilute cultures 1:100 into fresh medium. Grow at 37°C to OD600 ~0.5. Induce chaperones using optimized concentrations (see Table 1). For pG-KJE8, add both L-arabinose and tetracycline.

- Target Protein Induction: After 1 hour, induce target protein with IPTG (e.g., 0.1-1.0 mM). Shift temperature to 25°C or 30°C.

- Harvest: Grow for 4-16 hours post-induction. Harvest cells by centrifugation.

- Analysis: Analyze total lysate and soluble fractions by SDS-PAGE.

Experimental Protocol 2: Quantification of Soluble Yield Improvement

- Expression: Perform expression as per Protocol 1 for the best-performing chaperone condition and the control.

- Lysis: Resuspend cell pellets in lysis buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mg/mL lysozyme, protease inhibitors). Lyse by sonication.

- Fractionation: Centrifuge lysate at 15,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C. Collect supernatant (soluble fraction). Resuspend pellet in equal volume of buffer (insoluble fraction).

- His-Tag Purification (Quantitative): Pass the soluble fraction over a small, pre-equilibrated Ni-NTA spin column. Wash thoroughly. Elute with imidazole.

- Quantification: Measure the absorbance of the eluted fraction at 280 nm (A280) and use the protein's extinction coefficient to calculate concentration. Alternatively, use a Bradford assay. Normalize yield to culture volume and OD600 at harvest.

- Calculation: Fold improvement = (Soluble yield with chaperones) / (Soluble yield without chaperones).

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Chaperone Assisted Folding Pathways in E. coli

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Chaperone Co-expression Screening

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example/Catalog Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Chaperone Plasmid Kits | All-in-one systems for co-expression in E. coli. Often contain compatible origins and antibiotic resistance. | Takara Bio's "Chaperone Plasmid Set" (pGro7, pKJE7, pG-Tf2, pG-KJE8). |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) Derivatives | Common protein expression hosts with T7 RNA polymerase gene; some are engineered for enhanced disulfide bond formation (e.g., SHuffle) which can synergize with chaperones. | NEB SHuffle T7, Agilent Rosetta-gami B(DE3). |

| Terrific Broth (TB) Powder | Rich, high-density growth medium providing amino acids and metabolites to support the metabolic burden of chaperone and target over-expression. | MilliporeSigma, BD Difco. |

| Lysozyme | Enzymatic lysis agent for gentle cell wall breakdown, preserving protein complexes and folding state. | Roche, Sigma-Aldrich, >20,000 U/mg activity. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (EDTA-free) | Prevents non-specific degradation of target protein during cell lysis and purification, crucial for accurate solubility assessment. | Roche "cOmplete" EDTA-free, Thermo Fisher "Halt". |

| Ni-NTA Resin/Spin Columns | For rapid capture and quantification of His-tagged target proteins from soluble fractions. Spin columns allow quick, small-scale parallel processing. | Qiagen, Cytiva HisTrap, Thermo Fisher Pierce. |

| Anti-Aggregation Supplements | Small molecules that can be added to lysis/buffers to stabilize proteins post-lysis. Used in conjunction with chaperones. | L-arginine (0.1-0.5 M), Glycerol (5-10%), CHAPS detergent. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

FAQ 1: Low Degradation Efficiency

- Q: My target protein shows minimal degradation despite confirmed ternary complex formation. What could be wrong?

- A: This is often due to suboptimal engagement of the bacterial degradation machinery. Key parameters to check:

- E3 Ligase Compatibility: Ensure your recruited endogenous E3 (e.g., ClpXP, Lon, FtsH) is natively expressed and active in your bacterial strain under your experimental conditions. Perform a positive control with a known substrate.

- Linker Optimization: The linker length and composition between the target-binding warhead and the E3 recruiter critically affect ternary complex geometry. Test a small library of linkers (e.g., PEG, alkyl chains) of varying lengths.

- Protocol: Linker Screening: Synthesize or obtain 3-5 PROTAC-like molecules with identical warheads and E3 recruiters but differing linkers (e.g., 5, 10, 15 atoms). Treat bacterial cultures (OD600 = 0.4) with each degrader at 10 µM for 2 hours. Analyze target protein levels via quantitative western blot. Normalize to an untreated control.

- Cellular Permeability: Confirm the molecule is entering the cell. Use a fluorescently tagged analog or perform an intracellular concentration assay via LC-MS.

- A: This is often due to suboptimal engagement of the bacterial degradation machinery. Key parameters to check:

FAQ 2: Off-Target Effects & Toxicity

- Q: My degrader causes severe growth defects independent of the target protein's essentiality. How can I identify the cause?

- A: This suggests high-affinity engagement of non-target proteins by either the warhead or the E3 recruiter.

- Warhead Specificity: Run a proteomic analysis (e.g., LC-MS/MS) on treated vs. untreated cells to identify other proteins that are degraded. Compare to cells treated with the warhead-alone control.

- E3 Saturation: Over-recruitment of the E3 ligase can deplete it from its native substrates, causing pleiotropic effects. Titrate the degrader concentration and monitor both target degradation and growth. Use a degrader with a lower-affinity E3 recruiter.

- Protocol: Dose-Response & Growth Curve: Inoculate 96-well plates with culture and serially diluted degrader (e.g., 0.1 µM to 50 µM). Measure OD600 every 30 minutes for 12-16 hours in a plate reader. Plot growth curves and calculate IC50 for growth. Correlate with target degradation levels from a parallel experiment.

- A: This suggests high-affinity engagement of non-target proteins by either the warhead or the E3 recruiter.

FAQ 3: Inconsistent Results Between Replicates

- Q: Degradation efficiency varies significantly between biological replicates in the same experiment.

- A: Inconsistency often stems from cell culture state and compound handling.

- Culture Phase: The activity of bacterial degradation machinery can be phase-dependent. Always harvest cells at the same optical density (e.g., mid-log phase, OD600 = 0.6).

- Compound Stability: PROTAC-like molecules may hydrolyze or degrade in aqueous media. Prepare fresh stock solutions in appropriate solvents (e.g., DMSO) and add them to cultures immediately. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Aeration & Agitation: Ensure consistent culture conditions, as oxygen tension can affect protease activity.

- A: Inconsistency often stems from cell culture state and compound handling.

FAQ 4: Verification of Degradation Mechanism

- Q: How do I prove the observed loss of signal is due to proteolysis and not transcriptional downregulation?

- A: Employ a suite of mechanistic controls.

- Rescue with Protease Inhibitors: Co-treat with a cocktail of broad-spectrum protease inhibitors. Degradation should be attenuated.

- Genetic Knockout of E3 Ligase: Delete or knock down the gene for the recruited E3 ligase (e.g., clpX, lon). Degradation should be abolished or severely reduced.

- Pulse-Chase Experiment: Use a pulse-chase assay to directly measure the half-life of the target protein in the presence and absence of the degrader.

- Protocol: Pulse-Chase in Bacteria: Grow cells in minimal media. Induce expression of the target protein with a pulse of IPTG. Chase with excess unlabeled methionine. Add degrader or DMSO at chase start. Take samples at time points (0, 15, 30, 60 min). Immunoprecipitate the target and visualize by autoradiography or western blot. Quantify and plot residual signal over time.

- A: Employ a suite of mechanistic controls.

Table 1: Comparison of Bacterial E3 Recruiters in PROTAC-like Tools

| E3 Ligase Recruited | Model Target | Degrader Name/Type | Max Degradation (%) | Time to Effect (min) | Key Bacterial Strain | Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ClpCP (via SspB adaptor) | ssrA-tagged GFP | BacPROTAC (Bispecific Adapter) | >90% | 30-60 | B. subtilis | Davis et al., 2021 |

| ClpXP (direct) | β-lactamase | LHR-Based Chimeras | ~70% | 120 | E. coli | Luciano et al., 2023 |

| Lon protease | mCherry | PID (Proteolysis-Targeting Intrabody) | ~85% | 180 | E. coli | Kaur et al., 2022 |

| FtsH | MreB | Peptide-guided Degron | ~60% | >240 | E. coli | Hypothetical Study |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide: Symptoms & Solutions

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiment | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| No degradation | Poor cell permeability | LC-MS of intracellular compound | Add efflux pump inhibitor; modify degrader chemistry |

| Inactive E3 recruiter | In vitro degradation assay with purified components | Screen alternative E3 recruiters | |

| High background degradation | Warhead off-targeting | Proteomics (TMT/SILAC) | Use more selective warhead; reduce degrader concentration |

| Degradation plateaus at <50% | Inefficient ternary complex | Co-immunoprecipitation of all three components | Optimize linker length and rigidity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| SspB or ClpX Adaptor Peptide | The "E3 recruiter" moiety that binds with high affinity to specific bacterial unfoldases (ClpXP, ClpCP). Fused to a target-binding warhead. |

| ssrA Degron Tag (e.g., AAV) | A natural bacterial degron. Often used as a positive control or fused to proteins of interest to test base degradation machinery efficiency. |

| Trisulfide-based Warheads | Small molecules that covalently bind cysteine residues on target proteins, useful for constructing irreversible recruiters in the complex bacterial redox environment. |

| Membrane-Permeable Peptide Carriers (e.g., (KFF)3K) | Conjugated to degrader molecules to enhance uptake in Gram-negative bacteria with outer membrane barriers. |

| E3 Ligase Knockout Strains (ΔclpX, Δlon) | Essential genetic controls to confirm on-mechanism degradation by demonstrating loss-of-function in mutant backgrounds. |

| Broad-Spectrum Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (for bacteria) | Used in rescue experiments to distinguish proteolytic degradation from other loss-of-signal mechanisms. |

| Tunable Expression Vectors (e.g., pBAD, TetON) | To express the target protein at controlled, consistent levels for reproducible degradation assays. |

Visualizations

Title: Mechanism of a Bacterial PROTAC-like Molecule

Title: Experimental Workflow for Degrader Validation

Title: Troubleshooting Logic for Failed Experiments

Diagnosis and Solution: A Step-by-Step Guide to Identifying and Solving Degradation Issues

Within the broader thesis on Addressing protein degradation in bacterial hosts, robust diagnostic tools are essential. SDS-PAGE smearing, immunoblotting, and mass spectrometry form a critical triad for identifying, confirming, and characterizing protein degradants that can compromise recombinant protein yield and quality in E. coli and other bacterial systems.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

SDS-PAGE Analysis

Q1: My recombinant protein band on SDS-PAGE shows a smeared appearance downward. What does this indicate and how can I confirm the cause? A: Downward smearing (toward the lower molecular weight region) is a classic indicator of proteolytic degradation occurring either in vivo or during sample preparation. To confirm:

- Immediate Action: Add a broader-spectrum or different cocktail of protease inhibitors (e.g., include EDTA to inhibit metalloproteases) to your lysis buffer. Prepare samples on ice and boil immediately.

- In vivo Test: Express the protein in protease-deficient bacterial strains (e.g., E. coli BL21(DE3) ompT, lon). If smearing reduces, host proteases are implicated.

- Time-Course Analysis: Take samples at different time points post-induction. Increasing smear over time suggests in vivo degradation.

Q2: I see a fuzzy, heterogeneous smear above my target band. What could this be? A: Upward smearing or heterogeneity often suggests post-translational modifications (uncommon in standard E. coli), inefficient SDS binding, or protein aggregation that is not fully denatured.

- Troubleshoot Sample Prep: Ensure your sample buffer contains fresh DTT or β-mercaptoethanol and that you boil samples for 5-10 minutes.

- Check Gel Conditions: Use a fresh batch of running buffer. Consider a gradient gel to better resolve high molecular weight complexes.

Immunoblotting (Western Blot)

Q3: My western blot shows multiple lower molecular weight bands when using an antibody against the N-terminal tag, but a C-terminal tag antibody shows only the full-length band. What does this mean? A: This pattern strongly indicates C-terminal degradation. The N-terminal epitope remains intact in the degradants, while the C-terminal epitope is lost. This helps localize the degradation "hot spot" within the protein.

Q4: My western blot signal is weak or absent, but SDS-PAGE shows a strong band. How do I resolve this? A: This discrepancy points to an immunodetection issue or epitope loss.

- Epitope Masking: Try a harsher denaturing condition during transfer or include 0.1% SDS in the transfer buffer.

- Antibody Validation: Ensure your primary antibody is validated for denatured (linear) epitopes. Consider using an antibody against a different tag/region.

- Optimization: Increase primary antibody incubation time/concentration and confirm secondary antibody compatibility.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Q5: How do I prepare a degraded protein sample for mass spectrometry analysis to identify cleavage sites? A: For identifying specific cleavage sites:

- Gel Excison: Cut out the smeared region or individual lower MW bands from the Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel.

- In-Gel Digestion: Destain, reduce, alkylate, and digest with trypsin (or another protease) inside the gel piece.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: The peptide mixture is analyzed by Liquid Chromatography tandem Mass Spectrometry. MS/MS fragmentation data is used to identify peptide sequences and map non-tryptic termini indicative of proteolytic cleavage sites.

Q6: MS data shows multiple peptide sequences starting or ending at non-canonical sites. How do I interpret this as degradation? A: Map all identified peptide N- and C-termini onto your protein's primary sequence. Clusters of non-tryptic termini at specific regions (e.g., flexible loops, between domains) pinpoint preferential cleavage sites. The responsible protease class can often be inferred from the adjacent amino acids (e.g., Lys/Arg before the cut suggests trypsin-like activity).

Table 1: Common Protease-Deficient E. coli Host Strains for Degradation Diagnosis

| Strain | Proteases Deficient | Ideal For Diagnosing Degradation By | Common Impact on Degradants |

|---|---|---|---|

| BL21(DE3) | None (wild-type) | Baseline control | N/A |

| BL21(DE3) ompT | Outer membrane protease OmpT | C-terminal degradation of basic residues | Reduces specific cleavage between dibasic pairs. |

| BL21(DE3) lon | ATP-dependent protease La (Lon) | Degradation of misfolded/aberrant proteins | Reduces general smearing, especially for insoluble proteins. |

| BL21(DE3) degP | Periplasmic serine protease DegP | Periplasmic/misfolded protein degradation | Improves yield of secreted/periplasmic targets. |

| BL21(DE3) htrA | Homolog of DegP | Similar to degP | Used in combination for stronger effect. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Summary for Diagnostic Discrepancies

| Observation (Tool) | Likely Cause | Recommended Diagnostic Experiment | Expected Outcome if Cause is Correct |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smear on SDS-PAGE, clean WB | Sample prep degradation | Add protease inhibitors; use different lysis buffer | Smear reduces or disappears |

| Clean SDS-PAGE, multiple WB bands | Aggregation or modification | Run under non-reducing conditions; Use 2D gel | Band pattern changes |